Case 5 Rectal bleeding in a pregnant woman

Sadie, a 38-year-old woman in her third pregnancy, attended the practice antenatal clinic at 32 weeks mentioned to her midwife that she had occasional bleeding from her back passage. She had had problems with ‘piles’ since her second pregnancy two years earlier. The midwife thought that she probably had piles again but suggested that she saw her GP.

If you had been her GP what would you have done?

Two weeks later Sadie saw Dr Arnold but was more concerned about severe heartburn. She mentioned that she was having trouble with her piles. The Dr Arnold prescribed Anusol and an antacid.

Sadie consulted a different GP in the practice, Dr Durrant, a month later because she was worried that the bleeding from her back passage was happening more frequently. The blood was on the paper and in the pan. She experienced discomfort when opening her bowels. She had been constipated for a few weeks. She had the occasional abdominal pain that she attributed to everything stretching as the pregnancy progressed. Dr Durrant reassured her that there was nothing serious going on. He advised her to increase her fluid intake and gave her a prescription for some lactulose and proctosedyl suppositories.

Sadie had a normal vaginal delivery at term. She and the baby were seen for their postnatal check at eight weeks. She said that everything was fine and she had no particular problems.

Would you have done anything differently?

Nine months later Sadie sought help from Dr Bradley for continuing problems with her piles. She had had intermittent bright red blood on opening her bowels since giving birth although she had not mentioned it at her postnatal visit. She no longer had any anal symptoms. For the past month she had been opening her bowels more frequently. She had not had any diarrhoea. There was no family history of colorectal cancer. She was not anaemic. Abdominal examination was unremarkable. A rectal examination was normal. Dr Bradley performed routine blood tests including a viscosity. These were all normal. When on review two weeks later the symptoms were unchanged Dr Bradley referred Sadie under the ‘Two week rule’. At colonoscopy there was a mid sigmoid colonic carcinoma.

Unfortunately histology following a left hemicolectomy showed local invasion and lymph node involvement. Sadie sued her GPs for delay in the diagnosis of her cancer and subsequent poor prognosis.

Expert opinion

Expert opinion

Was the management of this patient reasonable or should she have been investigated sooner?

Studies have shown that rectal bleeding is common in the general population (Crosland & Jones, 1995). A questionnaire study of 6000 adult patients found that 26% of women under the age of 40 had experienced rectal bleeding in the previous 12 months (Thompson et al., 2000). Most patients do not present to doctors with their symptoms. This phenomenon, of the high frequency of symptoms in the community that are never reported to doctors, is often referred to as the ‘Symptom Iceberg’ (Hanny, 1979). One of the consequences of this ‘Symptom Iceberg’ is that patients who present to their doctor specifically with rectal bleeding are likely to have a much higher risk of having colorectal cancer (even though the risk may still be very low) than patients who do not volunteer the symptom but respond in the affirmative to a question (on a questionnaire or from a doctor) about whether or not they have experienced rectal bleeding.

A 2007 study by Roger Jones looked at a computerized database of 750 000 patients in primary care and found that 0.2% of women aged less than 45 with rectal bleeding had colorectal cancer (CRC) (Jones et al., 2007). Lewis et al (2002) estimated that the prevalence of undiagnosed CRC in a 35 year old presenting with rectal bleeding is 1 in 11 574.

It could be argued that it would have been prudent to perform a proctoscopy to confirm the presence of piles. However, in 1992 a survey showed that only 70% of general practices possessed proctoscopes and, in those practices that did, only three-quarters of the doctors used them (Rubin, 1995). It is unlikely that a GP would perform a proctoscopy late in the third trimester of pregnancy. Had the GP reviewed the woman’s recent past history and enquired about her rectal bleeding at the postnatal check, they might have done a proctoscopy. In this case, finding piles, which can co-exist with colorectal carcinoma, would have given false reassurance. However it would have enabled the GP to provide further treatment and arrange appropriate follow up and safety netting.

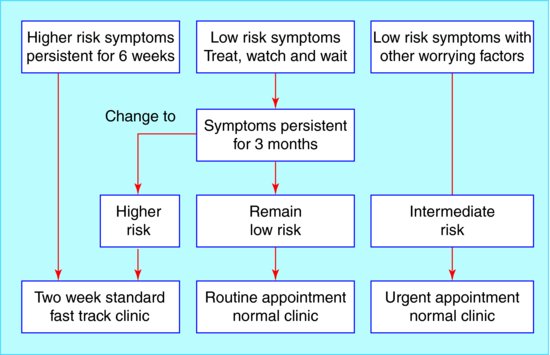

Managing a patient with rectal bleeding, who falls within ‘Two Week Rule’ guidance, is straightforward. This case illustrates the difficulty posed by low risk patients. Rectal bleeding with anal symptoms (such as discomfort) is considered ‘Low Risk’ at any age. The April 2002 Health Referral Guidelines for Bowel Cancer state (p. 36): ‘Rectal bleeding as a single symptom is of little diagnostic value. Its value is increased when it occurs in association with a change in bowel habit and when it occurs without anal symptoms.’ Thompson et al. (2003) has outlined a ‘Treat, watch and wait’ policy for patients with low risk symptoms (rectal bleeding with an anal cause and no change in bowel habit to loose frequent stools). This management plan is illustrated in Case Figure 5.1 from the August 2003 article by Thompson.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree