CHAPTER 49. Organ Donation and Tissue Transplantation*

Teresa J. Shafer

Other than a few papers in medical journals during the 1970s and early 1980s (after cadaver kidney recovery became more commonplace), little has been published concerning the effect of a medical examiner/coroner (ME/C) on organ retrieval efforts since kidney transplantation began in the United States in the late 1950s. Only since the early 1990s and the decade that followed has the issue of ME/C cooperation and its effect on organ donation been examined with a critical eye. Organ donation and transplantation has changed substantially since the late 1970s. Before the 1980s when transplantation became more successful, commonplace, and organized, bodies were transported to the medical examiner’s office following death and the autopsy was conducted unencumbered by requests for organs. This practice quickly became antiquated as organs became immediately and desperately needed for the thousands of people in communities throughout the United States waiting for organ transplants. Currently, nearly 18% of those waiting for a heart and 14% of those waiting for a liver will die before an organ becomes available. A person dies every two hours in the United States waiting for an organ (United Network for Organ Sharing [UNOS], 2009).

Nationwide, more than 100,000 people are waiting for lifesaving or life-enhancing organ transplants, yet only approximately 25,000 organs from 7500 organ donors have been available each year (UNOS, 2009). The organ donor shortage is the foremost challenge faced by the transplant community. Until 2003, organ recovery had not significantly increased in recent decades. In 2003, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) launched the Organ Donation Breakthrough Collaborative (ODBC). Organ donation increased a cumulative 22.5% from October 2003 to October 2006 (Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network [OPTN] and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients [SRTR], 2004; Shafer et al., 2006 and Shafer et al., 2008). This nationwide effort resulted in broad sharing of identified Best Practices and process improvements in organ procurement organization (OPO) and across the largest donor hospitals in the country. Because of this nationwide effort, donation increased as stated previously, and the number of organ donors has remained above the precollaborative (pre-2003) levels.

Many past and continuing efforts in addition to the ODBC have been made to maximize organ donation, most with small to modest success. They include the following:

1. Studying methods to increase public acceptance of organ donation (Ganikos, McNeil, Braslow, et al., 1994)

2. Understanding and implementing Best Practices to increase family consent for donation (Ehrle et al., 1999, Siminoff et al., 2001 and Siminoff et al., 2006)

3. Understanding and implementing methods to increase consent rates and donation within the minority populations (Shafer, Wood, Van Buren, et al., 1997)

4. Focusing on and improving organ procurement organization and hospital processes and collaboration to increase donation (Beasley, Capossela, Brigham, et al., 1997)

5. Studying healthcare professionals’ attitudes and their effects on organ donation (Siminoff, Arnold, & Caplan, 1995)

6. Exploring the possibility of using financial incentives to increase organ donation (Council of Ethical and Judicial Affairs, 1995)

7. Implementing required request legislation (U.S. Code Annotated, Title 42, 1987)

8. Exploring public policy initiatives such as presumed consent and mandated choice (Council of Ethical and Judicial Affairs, 1994)

9. Studying, proposing, or implementing other major legislative, regulatory, and policy initiatives (Siminoff, Arnold, Caplan, et al., 1995)

10. Increasing the use of “marginal” or older donors and expanding donor medical suitability criteria, including the use of organs from non–heart-beating donors (Kauffman, Bennett, McBride, et al., 1997)

11. Standardizing hospital requirements for donation programs (The Joint Commission, 2009)

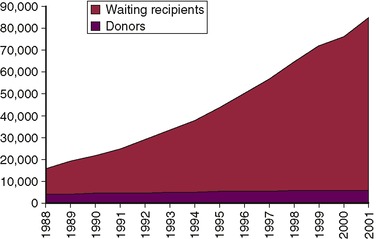

Before 2003, compared to the growth in the waiting list each year, the number of organ donors had remained relatively flat since 1986 (UNOS, 2004). In fact, the growth in organ donors averaged only 3.5% per year (Table 49-1). In contrast, the recipient waiting list grew at 10 times that rate, significantly and steadily increasing during the same time (Fig. 49-1). Put simply, the number of organ donors continues to lag far behind the number of people waiting for a lifesaving organ.

| NA: not applicable. | ||||||

| *From Southeastern Organ Procurement Foundation, Richmond, VA. | ||||||

| †1980-1987. From Evans, R. W. (1992, June). The National Cooperative Transplant Study. United Network for Organ Sharing/Health Care Financing Administration. Health and Population Research Center, Battelle-Seattle Research Center, Seattle, WA. BHARC-100-91-020, Control Number 01. | ||||||

| All data are from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) unless otherwise indicated. U.S. Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients and the Organ Procurement Transplant Network: Transplant Data 1989-2000. (2001, February 16). Rockville, MD and Richmond, VA: HHS/HRSA/OSP/DOT and UNOS. | ||||||

| Year | Persons on Waiting List | Percentage Increase in Patients on Waiting List | Cadaveric Organ Donors | Percentage Increase in Organ Donors | Cadaveric Organ Transplants | Percentage Increase in Organ Transplants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 5072* | — | 5038† | NA | ||

| 1981 | NA | — | 5041† | 0.1 | NA | |

| 1982 | NA | — | 2300† | 7.4 | NA | |

| 1983 | NA | — | 2705† | 17.6 | NA | |

| 1984 | NA | — | 3290† | 50.6 | NA | |

| 1985 | NA | — | 3637† | 10.6 | NA | |

| 1986 | NA | — | 3990† | 9.7 | NA | |

| 1987 | 13,115 | 159 | 4000† | .3 | NA | |

| 1988 | 16,034 | 22.3 | 4084 | 2.1 | 10.783 | |

| 1989 | 19,169 | 19.6 | 4019 | –1.6 | 11,208 | 3.9 |

| 1990 | 50,914 | 14.3 | 4509 | 12.2 | 12,858 | 14.7 |

| 1991 | 23,901 | 9.1 | 4526 | 0.4 | 13,318 | 3.6 |

| 1992 | 28,987 | 50.3 | 4520 | –0.1 | 13,471 | 1.1 |

| 1993 | 33,181 | 14.5 | 4861 | 7.5 | 14,635 | 8.6 |

| 1994 | 37,365 | 12.6 | 5100 | 4.9 | 15,083 | 3.1 |

| 1995 | 43,333 | 16.0 | 5360 | 5.1 | 15,780 | 4.6 |

| 1996 | 49,445 | 14.1 | 5418 | 1.1 | 15,784 | 0 |

| 1997 | 55,751 | 12.8 | 5479 | 1.1 | 15,044 | –4.7 |

| 1998 | 62,740 | 12.5 | 5798 | 5.8 | 16,748 | 11.3 |

| 1999 | 69,054 | 10.1 | 5810 | 0.50 | 16,810 | 0.4 |

| 2000 | 76,115 | 10.2 | 5985 | 3.0 | 17,081 | 1.6 |

| 2001 | 84,798 | 11.4 | 6081 | 1.6 | 17,591 | 3.0 |

| 2002 | 80,790 | 1.6 | 6190 | 1.8 | 18,290 | 3.7 |

| 2003 | 83,731 | 3.6 | 6457 | 4.3 | 18,665 | 2.1 |

| 2004 | 87,146 | 4.1 | 7150 | 10.7 | 20,044 | 7.4 |

| 2005 | 90,526 | 3.9 | 7593 | 6.2 | 50,501 | 5.8 |

| 2006 | 94,441 | 4.3 | 8020 | 5.6 | 22,196 | 4.6 |

| 2007 | 97,980 | 3.7 | 8086 | 0.9 | 22,049 | −0.7 |

| 2008 | 108,200 | 2.9 | 7312 | −9.6 | 20,048 | −9.3 |

Despite numerous local public education activities, legislative actions—such as request and contractual requirements between hospitals and OPOs mandated by federal law, involvement of the Surgeon General and the U.S. General Accounting Office U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. General Accounting Office, 1993)—and nationwide public awareness campaign themes, there were no significant increases in organ donation in the 1990s.

Medical professionals sometimes mistakenly believe that only young, healthy individuals can be organ donors. While the ideal organ donor has an irreparable brain injury, is relatively young, is a trauma victim, is otherwise medically well, and has excellent multiorgan function, donors dying under these circumstances are becoming more and more uncommon because of demographic changes regarding age in the country’s population (Morrissey & Monaco, 1997). Transplantation professionals look at all brain-dead patients, regardless of age or current medical condition, as potential organ donors. Nonetheless, the shortfall of organ donors has continued, despite the fact that donor criteria have been greatly relaxed in order to recover more organs for those who wait. Given this shortage of organs, every suitable donor from whom organs are not recovered results in the loss of lives.

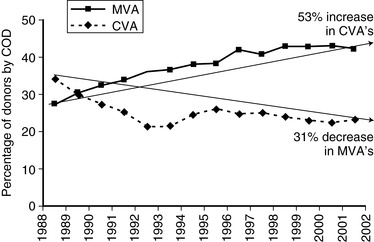

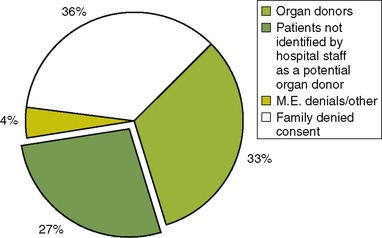

Actual recovery of organ donors falls far short of the potential donor pool for a number of reasons, chief among them being (1) denied consent from families for organ donation when asked to donate and (2) nonreferral of the potential donor by the hospital to the OPO (Fig. 49-2). Additionally, to some extent, downward trends in motor vehicle accidents, gunshot wounds, and other traumatic brain injuries play a role (Sosin, Sniezek, & Waxweiler, 1995). Decreased speed limits as well as helmet and seat belt laws have greatly decreased the number of motor vehicle accidents, with a concomitant decrease in organ donors who have died under these circumstances. Organ donors whose circumstance of death was a motor vehicle accident decreased 31%, from 34.3% in 1988 to 23.5% in 2002. Over the same period, organ donors with the diagnosis of cerebrovascular death rose 53%, from 27.7% to 42% of all deaths (Fig. 49-3).

|

| Fig. 49-2 |

Further, with age being greater in the population of individuals dying of cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs), along with the relaxed restrictions on donor criteria, recovery of organs from donors older than 65 grew an astounding 900% for the same period, from 0.9% in 1988 to 9% of all donors in 1999 (UNOS, 2002). In fact, maintaining recovery levels along with the minor increases in donors has only been achieved through the recovery of older, more marginal donors.

Impact of the Medical Examiner on Organ Donation

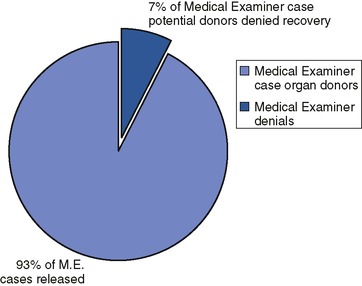

Another reason for the organ shortage lies directly in the sphere of forensic death investigation. Despite widespread attention in 1994 to organ donor losses resulting from medical examiner denials, many areas of the country still needlessly lose significant numbers of organ donors because a local medical examiner refuses to release the organs of potential donors. In this chapter, the term medical examiner will be considered in the legal sense, the same as coroner and justice of the peace. Medical examiners are the physicians who are trained to do autopsies. Coroners and justices of the peace may have a background in law enforcement. In counties that do not have medical examiners, coroners or justices of the peace may give authorization for organ and tissue recovery. In some instances, the justice of the peace or a coroner may possess the legal authority to release such organs, so this information on organ recovery also applies to these officials except when a reference is made to specific medical duties such as performing an autopsy (see Chapter 16, 2nd edition; “Medical Examiners,” 1994; “Organ Releases,” 1994; Shafer, Schkade, Warner, et al., 1994; “Study Finds,” 1994; Voelker, 1994). The most recent study on this issue indicates that the loss of transplantable organs because of medical examiner refusals remains close to the 1992 level, about 7% (Shafer, Schkade, Evans, et al., 2004) (Fig. 49-4).

This is particularly a problem with potential pediatric organ donors who have died because of suspected child abuse or sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Nonrecovery of organs in this age group is a significant contributing reason for the pediatric death rate on the waiting list for a liver transplant in children age five and under. In 1990-1992, 22% of all ME/C denials were from child abuse cases, compared with 25% in 2000-2001. In 1990-1992, 73% of child abuse potential organ donors were denied, compared with 44% in 2000-2001. In one report of loss of pediatric organs for transplantation because of ME/C denials, 20.1% of all ME/C denials involved children younger than one year old increasing to 41% of all denials involving children age 10 and younger. Because only 183 actual organ donors in 2000-2001 were younger than one year old, it followed that nearly one third (31.1%) of these potential donors were denied recovery (Shafer, Schkade, Evans et al., 2004). Denials associated with pediatric potential organ donors remain a serious issue.

Medical examiners play a vital role in organ transplantation and could significantly increase organ recovery in the United States if cases falling under their jurisdiction, after appropriate examination, were routinely and expeditiously released for organ recovery and transplantation. Because litigation in general has increased over the years, the development of protocols detailing procedures used in recovering evidence before organ recovery might assist ME/Cs in releasing cases for organ donation. If such protocols, as well as firm public policy requiring organ release in ME/C cases, were put into place throughout the United States, a truly significant increase in organ donors would be accomplished. Such firm public policy would mandate that medical examiners and transplant professionals collaborate to satisfy mutual needs.

Therefore, medical examiners and forensic nurse examiners (FNEs) have a key role in the U.S. public health system when working with the dead—and the living—in a number of ways. The role of the FNE in death investigation puts him or her in an ideal position to affect the lives of patients throughout the United States waiting for an organ that will give them a second chance at life. The FNE works directly with medical examiners and organ procurement specialists to ensure that all forensic evidence is collected and that all medically suitable organs are recovered. With close cooperation between the FNE and OPO, the expectation should be that in cases in which the family has consented to donate and the potential donor is medically suitable, organs for transplantation will be recovered 100% of the time.

The FNE role in tissue donation will be discussed separately in this chapter, following the discussion on organ donation.

Impact of the Forensic Nurse on Organ Donation

As a public policy issue, it is crucial that the supply of organs and tissues for transplantation be maximized. Congress acknowledged this public policy goal by mandating hospital protocols that offered organ donation as an option in appropriate cases and, in 1997, by mandating by regulation that all U.S. hospitals participating in the Medicare and Medicaid Program refer every death occurring within the hospital to an OPO [42 U.S.C.§273(b)(2)(k)]. One source of donated organs that can be tapped immediately is the group of organs lost from ME/C denials of organ recovery. Because of this issue, nurses practicing in the emergent field of forensic nursing are in an ideal position to assume a leadership role in improving the public health crisis in the United States resulting from the desperate shortage of organs.

Nurses have longed served the public through the many roles they have assumed, and the roles they have been asked to assume, throughout the history of nursing. No other healthcare professional so touches the basic human needs of people. Nurses are accustomed to dealing with a variety of clients, including patients, their families, and the communities in which they live; nurses do this while juggling many priorities and tasks. It is cliché to attribute this quality to a feminine nature, but, nonetheless, this cooperative and sometimes “nurturing” quality can be attributed to nurses—male or female—who have historically demonstrated, through practice, the caregiving role in the greatest sense of the word. Historically, when entering specialty-nursing roles, nurses have not given up their nurturing, caring side; they have not become more circumscribed, elevated, and less accessible to their patients and community. Nurses never abandoned their generalist, their Nightingale image. The ability to see the larger picture is what enables FNEs to look beyond the important but unidimensional need of death investigation and see the waiting recipients, the potential donors and their families, and the community at large. The FNE, by keeping the big picture in view, ensures that organ donation is accomplished in all cases simultaneously with competent death investigations, a primary responsibility of the FNE.

It is reasonable and appropriate to expect a FNE to ensure that the forensic investigations are grounded, thorough, and expedient, and that they work in harmony with the recovery of lifesaving organs intended for transplantation. Such a holistic approach of care to a variety of individuals (waiting potential transplant recipients, donor, donor family crime victim, crime victim’s family, police, attorneys, transplant team, and community members from both the donor’s and the recipient’s respective communities) involved in the organ donation and forensic examination process is certainly not foreign to the nursing profession. It is here where the FNE can excel—in investigating the death of the potential donor using the highest possible standards of forensic death investigation, ensuring the transplantation of the potential donor’s organs, and resolving any conflicts between the two in the process.

The resolution of any perceived conflicts between organ recovery and death investigation has been referred to as a win-win situation in that forensic evidence is collected and organs are recovered. The term win-win is certainly an oversimplified description of the interdisciplinary process through which an FNE works to ensure, in a holistic approach to care, that the community is served.

National System

The National Organ Transplant Act (1984) mandated the establishment of both the national OPTN and the national SRTR. The OPTN and SRTR were to be administered by a private, nonprofit entity through contracts with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The UNOS administers the OPTN, and the University Renal Research and Education Association (URREA) administers the SRTR. UNOS is responsible for promoting, facilitating, and scientifically advancing organ procurement and transplantation throughout the United States while administering a national organ allocation system based on scientific and medical factors and practices. URREA is responsible for the ongoing evaluation of the scientific and clinical status of transplanted organs and OPO performance for recovery of organs for transplantation.

Policies governing the transplant community are developed by the OPTN membership through a series of regional meetings, national committee deliberations, a public comment period, and final approval by a board of directors that includes both physicians and nonphysicians. The OPTN has adopted policies to ensure equitable organ allocation to patients on the national waiting list. These policies forbid favoritism based on political influence, race, sex, or financial status; they rely, instead, on medical and scientific criteria (Bowers & Servino, 1992).

Procurement Organizations

Organ procurement organizations (OPOs) are nonprofit, government-certified agencies that facilitate organ recovery services in designated areas of the United States. OPOs are the link between the organ donor and the transplant center and recipient. Highly specialized and trained OPO staff members, who normally come from nursing backgrounds, provide these major services:

• Assist hospitals with procedures and education on donation

• Receive all organ and tissue donor referrals

• Evaluate potential donors

• Discuss and obtain consent for donation from families

• Medically manage patient for organ preservation

• Coordinate surgical organ and tissue recovery

• Allocate organs

• Transport organs to transplant centers

• Arrange importing/receiving/procuring of distant organ (imports)

• Enter and maintain recipient waiting lists

• Provide professional education for nurses, physicians, and other healthcare professionals

• Provide public education about donation and increase public awareness of the need for organ donation

• Provide public policy advice and assist in public policy formulation

• Maintain an extensive database on organ donation and provide data to UNOS and other governmental agencies

OPOs can also facilitate tissue recovery either directly or indirectly by referring the potential donor to a tissue, skin, or eye bank. OPO and tissue personnel are available 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, to assist physicians, nurses, and families as needed (Bowers & Servino, 1992).

Donation and Death Investigation Process

The organ donation process is complex. Box 49-1 provides a general overview of the steps involved during the donation process. The major steps always occur, but the sequence and timeframe between events vary depending on the individual circumstances. Once the family consents to organ or tissue donation, the timeframe for this process will vary from a few hours up to 20 or more hours. Coordinated teamwork between the physicians, nurses, hospital staff, surgical recovery teams, and the procurement coordinator are critical for assuring the viability of the transplant graft. Four major steps generally define the donation process: potential donor identification and referral, consent, donor evaluation and maintenance, and organ and tissue recovery (Seem & Skelley, 1992).

Box 49-1

1. The patient

• is admitted to hospital.

• does not respond to efforts made to save the patient’s life.

• has sustained head injuries, bleeds, or anoxic events severe enough that patient will not recover.

• is pronounced brain dead after evaluation, testing, and documentation.

2. Referral is made to the organ procurement organization (OPO) to evaluate the patient as an organ/tissue donor.

3. The patient is evaluated by the OPO, and the family is approached about donation.

4. Consent for donation is requested to initiate the recovery process.

5. The medical examiner’s (ME’s) cases need the ME’s authorization to proceed with donation.

6. The donor is maintained on a ventilator, stabilized with fluids and drugs, and undergoes numerous laboratory and diagnostic tests.

7. Recipients are identified for the placement of organs.

8. Surgical teams are mobilized and coordinated to arrive at donor hospital for removal of organs and tissues.

9. The donor is brought to the operating room on the ventilator once the surgical teams have arrived at the local hospital where the donor is located.

10. Multiple organ recovery is performed with organs being preserved through special solutions and cold packaging. Ventilator support is discontinued following cross-clamping of the aorta.

11. Tissue donation occurs once the vascular organ donation is completed.

12. The donor’s body is reconstructed and surgically closed.

13. The donor’s body is released to the funeral home.

Note: Confidentiality is maintained for the donor family and recipients.

Donor criteria

More than 20 different organs and tissues can be transplanted or used in research. Each potential donor’s options for organ and tissue donation is assessed by a procurement specialist. Criteria have expanded, so it is essential that an organ or tissue procurement organization be referred to every single hospital death for evaluation as a potential donor.

Organ donors are previously healthy individuals who suffer irreversible and catastrophic brain injury resulting in brain death with sustained cardiac function (heartbeat). To sustain cardiac function, they are maintained on a ventilator and clinically managed with appropriate fluids and medications until the organs are removed. Transplantable organs include heart, kidney, liver, lung, pancreas, and small bowel. Some physicians accept non–heart-beating donors as organ donors.

Tissue donors, on the other hand, are non–heart-beating. That is, tissue is most commonly obtained from a person who has died of cardiopulmonary arrest or from a solid-organ donor after removal of transplantable organs. Transplantable tissues include dura, eyes, corneas, skin, fascia, cartilage, tendons, ligaments, bones (e.g., ribs, femurs, tibias, fibulas, and ilium), saphenous veins, and heart valves. Tissues are recovered within 24 hours after death if the donor’s body has been refrigerated (6 hours or sooner is preferable for eyes) (Seem & Skelley, 1992).

Brain death

Brain death is a medically and legally valid declaration of death and is defined as the complete and irreversible loss of brain and brain stem functions. Brain death is determined by considering the following factors:

• There is a known etiology for the brain death.

• Reversible conditions, such as hypothermia, drug intoxication, or metabolic abnormalities, must be excluded.

• The patient must be clinically examined to demonstrate (1) absence of cerebral function, (2) no spontaneous movements, (3) no response to stimulation, (4) no brain stem reflexes, and (5) apnea.

• Diagnostic tests, such as CT scans, electroencephalograms (EEGs), and cerebral blood flow (CBF) studies, may be performed in conjunction with a clinical exam.

• CBF studies may be used as a confirmatory test for the diagnosis of brain death.

• Brain death can be diagnosed in full-term newborns older than seven days, provided that confirmatory tests are employed.

• When brain death is diagnosed, the patient is declared dead and appropriate documentation is made in the patient’s record.

• If the brain-dead patient is to be an organ donor, organ donor management interventions must be continued until the time of organ recovery.

• If the patient is not to be an organ donor, mechanical support of the body functions can be terminated (Seem & Skelley, 1992).

Donor identification and referral

First, the hospital staff identifies a potential donor and makes a referral to the local OPO. An attending or consulting physician, a staff nurse, or designated hospital staff may complete this function. Organs are recovered from individuals declared dead on the basis of brain death criteria (98% of all U.S. organ donors) or individuals who have sustained a severe neurological injury, the family chooses to withdraw life support, and cardiac death occurs in such a manner that organ recovery can proceed immediately (5 to 10 minutes) after cessation of cardiac function (less than 5% of U.S. organ donors) (UNOS, 2004).

The physician determines death according to neurological criteria and informs family members of the patient’s death. The decedent’s family members in most cases are not approached about donation until it has been determined that they understand that “brain death” is death. Family members often raise the issue of donation themselves before this time, and hospital or OPO staff may make a premention of donation as the futility of care becomes evident to all involved. The OPO procurement coordinator is able to provide specific information about donation to the family in a way that ensures informed consent is accomplished and the benefits of donation for both the donor family and the waiting recipients are fully explained. If the family wishes to donate, a consent form, supplied by the hospital or OPO coordinator, is completed and signed (Seem & Skelley, 1992).

Up until this point, the medical examiner’s office has usually not been contacted. It is normally only after the official declaration of death that the medical examiner is notified. However, the OPO coordinator is normally on the scene much earlier than this point and ensures that the medical examiner is notified immediately following pronouncement of death. At this time, the FNE might join the OPO coordinator at the hospital, whether in the emergency department or in the intensive care unit, and begin collecting forensic evidence.

Table 49-2 lists items that may be provided to the medical examiner’s office by the hospital or OPO staff. In some circumstances, the FNE might facilitate collection of such evidence by going directly to the hospital in which the potential organ donor is located and speaking directly with the OPO and hospital staff. This provides for enhanced communication between the medical examiner’s office and hospital/OPO staff serving not only the purposes of collection of evidence and establishment of chain of custody, but also the reinforcement of the role of the FNE in the healthcare community. Additionally, it allows the FNE to examine the body in the hospital, soon after death, so that an exam by a trained forensic examiner is conducted before organ recovery, and that, in addition to organ recovery in all situations in which there are one or more organs suitable for transplant in a brain-dead patient, more tissues (bone, skin, eyes) might be released for donation. The FNE’s role is to collaborate with medical examiners, hospital staff, and organ procurement professionals.

| *Each office and OPO is different and has its own arrangement. This is a list of those items that may prove useful to the medical examiner in certain circumstances. | |

| ITEM | Comment |

|---|---|

| Two red-top tubes of blood | Labeled with the donor’s name, medical examiner case number, date and time of collection, and initials of the collecting party. All should be sealed inside of a protective container with evidence tape. (Whenever possible, a pretransfusion serum sample, so labeled, should be provided.) |

| Urine sample | Labeled with the donor’s name, medical examiner case number, date and time of collection, and initials of the collecting party. All should be sealed inside of a protective container with evidence tape and admission. (Whenever possible, an admission urine sample, so labeled, should be provided.) |

| A copy of the OPO medical record | To be placed in a plastic bag. |

| Polaroid photos of the body | To be taken before any preoperative procedures, with the date and medical examiner case number written in black on a white sheet of paper, which is to be displayed in the foreground of the photo. (The medical examiner is responsible for training OPO staff in the appropriate techniques for obtaining such photographs.) |

| Additional photos of the body will be taken preoperatively, using a 35-mm camera and with the medical examiner case number and date displayed as above | Each roll of film is to contain photos of only one donor. No photos of any other subject will be included on the roll. The roll of film will be placed in a film-processing envelope provided by the medical examiner, labeled with the date and medical examiner case number, and delivered by OPO staff to the medical examiner’s office. |

| An operative note dictated by one of the transplant surgeons in attendance noting all operative findings | Delivered to the medical examiner in a timely manner. |

| Written reports of any organ biopsies performed by OPO or transplant centers | To be submitted upon request of the medical examiner’s office. |

| X-rays or reports of x-rays | In child abuse cases, a computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head may be useful. |

Family consent

Acute care hospitals are legally obligated to offer families of potential organ donors the option of organ and tissue donation. Approaching a grieving family about donation can be difficult. But research reveals that when the conversation is sincere and sensitive, the majority of families experience important short- and long-term benefits whether or not they choose to donate. In fact, families can become angry and frustrated when denied the opportunity to donate. Research on public attitudes and family experience of donation repeatedly have come to the same conclusion: the manner in which the donation request is made is the main factor in a family’s ultimate decision, regardless of preexisting attitudes.

Approaching a family about donation requires coordinated efforts among the physician, hospital staff, and the OPO coordinator. The physician has the responsibility to inform the family of their relative’s death. Time must be allowed for the family to accept the reality of death before raising the question of donation. The person who is most comfortable and knowledgeable about donation should discuss donation with the family, and that individual is usually the OPO coordinator. OPO coordinators bring knowledge, experience, and a confidence in their ability to handle all aspects of the donation process. They know firsthand the benefits that the process offers the family (Ehrle, Shafer, & Nelson, 1999). Donation is a process. Obtaining consent does not consist of simply asking the family if they wish to donate, in essence, “popping the question.” Informed consent takes time; OPO staff members have the time that busy physicians and nurses do not have. OPO staff members spend significant time, often many hours, with families during the donation process (Shafer, Schkade, Evans, et al., 2004). An investment of the time of bedside nurses and physicians is not possible in today’s environment of limited healthcare resources.

The forensic nurse examiner can reinforce with the family the value of organ and tissue donation in cases in which hospital and OPO staff are making the request for donation. If the FNE is making the request for tissue donation in a case that has not yet been consented by hospital or OPO staff, the FNE should ensure that the family is fully informed about the value of tissue donation before requesting their consent.

The family should be provided sufficient information to make an informed decision about whether or not they wish to donate organs or tissues. The positive benefits of donation help families cope with their loss by helping to save the life of someone else, by having their loved one live on in a sense, and by fulfilling the implicit and explicit wish of their loved one.

Concerns of the family should be anticipated and addressed in a forthright manner. A person’s reluctance to donate is most often rooted in misinformation or a lack of information. Before beginning the donation discussion, OPO coordinators assess families as to their knowledge and acceptance of brain death as death. Families are informed that (1) the OPO pays all costs involved with donation, (2) there is no disfigurement of the body and that an open-casket funeral is possible, (3) their loved one will feel no pain because their loved one is dead and the brain has no ability to sense or convey pain, and (4) all major religions and religious traditions allow organ donation. Some families have questions about how the organs are distributed and to whom they are given. They are informed that there is a national OPTN that monitors and regulates organ distribution to assure fairness. Buying and selling of organs is illegal (Seem & Skelley, 1992).

Once the OPO coordinator has obtained consent for donation, the FNE can confer with the family and answer any questions they might have regarding the process that will occur following donation with the autopsy. Families often have questions about the autopsy process, which, by default, nurses and OPO coordinators answer because no representative of the medical examiner’s office is present. This is another role the FNE could fill in a more informed manner than hospital or OPO staff.

Donor evaluation

Evaluation begins at the time of referral. The referring physician or nurse provides specific information about the donor, such as age, sex, race, date and time of admission, diagnosis, and vital signs (admission and current). The donor’s hemodynamic stability is maintained through mechanical ventilation until the time of organ removal. Individuals who have died from cardiopulmonary arrest may be acceptable donors of corneas, skin, bone, heart valves, and other tissue. Other initial criteria for donor suitability include age limits specific to each organ and tissue and an absence of metastatic cancer or unresolved systemic infections.

Once the procurement coordinator arrives at the donor hospital, he or she begins with a thorough chart review. A review of the emergency department admission record and the emergency medical services run report is essential. Information regarding the cause of admission, including details such as a cardiac or respiratory arrest, ejection from a vehicle, and submersion in water, is vital to the multiorgan donor workup. Knowledge of such events may indicate whether the organs have suffered significant damage. A review of physician and nursing notes provides an overall picture of the patient’s status. A complete assessment of blood pressure and temperature curves, use of vasoactive drugs, and episodes of hypotension, hypertension, bradycardia, and tachycardia are noted. Progress notes should provide documentation of the patient’s brain death determination. Brain death laws vary from state to state, as do determination and criteria policies from hospital to hospital.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access