CHAPTER 47. Pediatric Emergencies

Nancy L Mecham

In most cases, when a child is sick, the parents or guardian should be encouraged to stay with their child during all phases of the visit. Fear and uncertainty surrounding the child’s condition, coupled with a loss of control of the situation, add to the stress that both the parent and child may be experiencing. Begin the assessment as soon as the child enters the emergency department (ED); approaching the child slowly while interviewing the parent is the best way to start the interaction with the child. Positive, caring interactions with the child and parent help alleviate the stress and facilitate assessment of the child. Calling the child by name, making direct eye contact, using simple understandable terms, and offering choices when appropriate are all basic guidelines that can be used with patients and families of all ages.

Most emergency nurses, regardless of practice area, will encounter a sick child at some point in their career. The ability to intervene in critical situations requires a strong foundation of knowledge and assessment skills. This chapter provides an overview of pediatric assessment and common pediatric emergencies. Pediatric trauma and child abuse are discussed in Chapter 28 and Chapter 48, respectively.

TRIAGE

Pediatric patients, defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as individuals less than 15 years of age, account for approximately 21% of annual ED visits nationally. 11 The triage nurse needs to have outstanding assessment, communication, and organization skills. The emergency nurse who becomes skilled at triage will also develop a “sixth sense” for identifying the “sick” infant or child.

A sick child in the ED can make nurses who are unfamiliar with children uneasy, just as an adult with chest pain can generate alarm in a pediatric nurse. Triage of a child does not require familiarity with every childhood disease, medication, and neurologic reflex or a horde of specialized equipment. Pediatric triage does require understanding of concepts related to pediatric emergencies, including the following:

• Anatomic, physiologic, and developmental differences between children and adults

• Recognition of conditions leading to pediatric arrest (hypoxia and shock) and appropriate interventions

• Effective communication with parents

• “Rules” of pediatric triage

Children are a challenge to evaluate when compared with adults for several reasons. Children often have nonspecific symptoms, such as fever, and communication can be difficult. In the younger infant, because of limited vocabulary and verbal skills, the nurse must depend on the parent and subtle clues from the child for history. A child’s response to illness or injury depends on his or her current developmental stage. Toddlers cling to parents, whereas adolescents are independent. Children compensate physiologically for longer periods in the face of illness; therefore they may not be outwardly symptomatic despite the presence of a life-threatening condition. Normal vital signs do not always indicate stability in the pediatric patient.

Special Pediatric Considerations

Some of the most significant differences between children and adults are found in the respiratory and circulatory systems. One of the most obvious anatomic differences is that infants and young children have larger tongues in proportion to the size of their mouths. This means that the tongue can easily obstruct the airway; proper positioning is often all that is necessary to provide airway patency. Because of the smaller diameter of their airway structures, children have increased airway resistance compared to an adult; small amounts of mucus or swelling exacerbate this difference and can easily obstruct the airway. Infants less than 4 months of age are obligatory nose breathers; any process that obstructs the nose can lead to respiratory distress. Cartilage of a child’s larynx is softer than in an adult. The cricoid cartilage is the narrowest portion of the larynx, providing a natural seal for endotracheal tubes. 13 The sternum and ribs of the pediatric patient are cartilaginous, the chest wall is soft, and intercostal muscles are poorly developed, leading easily to fatigue. All of these factors contribute to a more inefficient respiratory system and the cause of frequent respiratory distress.

There are some specific differences in the cardiovascular system of the pediatric patient that have clinical significance. Infants and children have a higher cardiac output than adults (200 mL/kg/min versus 100 mL/kg/min). 5 Cardiac output is the volume of blood ejected by the heart each minute; it is defined by the following equation: heart rate × stroke volume = cardiac output. A higher cardiac output is required because the pediatric patient has a higher oxygen demand as a result of a higher metabolic rate and greater oxygen consumption (6 to 8 mL/kg/min compared to 3 to 4 mL/kg/min in adults). In pediatric patients the myocardial fibers are shorter and less elastic, which means the myocardium has poorer compliance and less ability to adjust stroke volume in an altered cardiac output state. This is why heart rate is such an important and sensitive indicator of cardiac output in pediatric patients. 13

Children have a greater percentage of total body water than adults (80 mL/kg versus 70 mL/kg in adults) and are more susceptible to volume depletion with even small loses that are not replaced. This is why children are at a greater risk for dehydration than adults. However, part of the challenge with pediatrics is that children can maintain an adequate cardiac output for long periods of time by compensating for fluid loss with an increased heart rate (tachycardia) and peripheral vasoconstriction. 13 Because of their strong compensatory mechanisms, 25% to 30% of circulating volume may be lost before a decrease in systolic blood pressure (SBP) occurs, indicating the child has progressed to a decompensated shock state. 13 By the time the shock state is recognized the child may already be in critical condition.

Neonates, term infants from birth to 28 days of age, and particularly preterm neonates, possess unique physiologic characteristics and should be assessed and treated very carefully. The thermoregulatory system is very immature in the neonatal period, and thus keeping newborns warm without overheating them can be a challenge. There can be serious consequences of hypothermia, as well as hyperthermia. Hypoglycemia, apnea, metabolic acidosis, and poor feeding can result from cold stress. Warm stress can also lead to poor feeding, lethargy, hypotonia, and hypotension. Simply taking care to not leave the newborn undressed or unwrapped for long periods of time during the ED visit is a simple way to avert problems. Other methods that may be used to keep the newborn warm include the use of warmed intravenous (IV) fluids, covering the head of the newborn, use of an overhead radiant warmer, or even the use of warm blankets. An effortless way to ensure thermoregulation of the newborn in the ED is to maintain a higher temperature in the room where the newborn will be examined. As a rule of thumb, if an adult in short sleeves is feeling warm, the room temperature should be about right for the newborn. However, as mentioned, overheating can become an issue for the newborn as well, so it is important not to overdo the heating methods. Temperature monitoring should not be overlooked. The neonatal immune system is also immature; therefore a fever of 100.4° F (38° C) is considered significant for a newborn. The inability to localize infections makes the neonate even harder to assess for infectious processes because they have fewer signs and symptoms. 10 Newborns, young infants, and children have limited glycogen stores and are vulnerable to hypoglycemia when stressed by an illness, injury, or cold stress.

Rules of Pediatric Triage

The following unofficial rules of pediatric triage may assist triage nurses in evaluating children.

2. Remember airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs)—children are different. Do not always focus on the obvious; a subtle, more serious problem can be overlooked.

3. Some children can talk, walk, and still be in shock; do not depend solely on the child’s appearance. Consider history and vital signs, but do not allow normal vital signs to give you a false sense of security.

4. Never tell parents their child cannot be evaluated in the ED, no matter what the chief complaint.

Pediatric Triage Evaluation

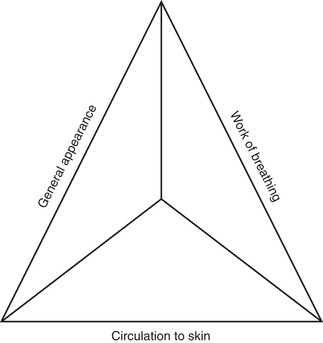

Depending on the facility, the triage assessment may be brief, limited to determining chief complaint and looking at the child, or it may be more comprehensive and include obtaining vital signs and providing treatment such as antipyretics, splinting, or ice packs. Whatever triage protocols or pathways exist, the first and most important aspect is prompt assessment with observation. This first assessment is sometimes referred to as the “across-the-room assessment,” or the “looks good–looks bad” assessment using the Pediatric Assessment Triangle (PAT). 10 The PAT uses three physiologic parameters that reflect severity of illness or injury: the child’s general appearance, work of breathing, and circulation to skin (Figure 47-1). General appearance refers to the child’s tone, interactiveness, consolability, look/gaze, and speech/cry. Work of breathing is evaluated by signs such as airway sounds, positioning, retractions, and flaring. Circulation to the skin is obtained by assessing skin color (pink, pale, gray, dusky, cyanotic). The parameters can be assessed in any order. 10 With experience and practice a triage nurse can look at a room of children and quickly sort out who needs to be triaged first.

|

| FIGURE 47-1 Pediatric Assessment Triangle. (From Emergency Nurses Association: Emergency nursing pediatric course provider manual, ed 3, Hawkins HS, editor, Des Plaines, Ill, 2004, The Association.) |

Primary Assessment

Primary assessment consists of evaluation of the ABCs and neurologic status of the child. ABCs may be the only part of the assessment performed in triage if the child has an emergent condition. The primary survey includes assessment of level of consciousness; respiratory effort, rate, and quality; skin color, temperature, and capillary refill; and pulse rate and quality. 13

Secondary Assessment

Secondary assessment consists of vital signs and head-to-toe survey. During triage, secondary assessment is usually limited to evaluating the area of chief complaint or focused examination. The rest of the examination is performed later in a treatment area. When performing a secondary assessment on a child, do not focus only on the obvious injury. Do not forget to take into account the patient’s chronic condition(s) or any significant past medical history when determining how high risk the patient may be (e.g., fever in the immunosuppressed patient or headache and vomiting in the patient with a ventriculoperitoneal [VP] shunt in place). Communicate your findings to other health care team members, and document your assessment.

History

Obtaining a standardized history of the child’s illness is an important part of the pediatric assessment. If the triage nurse identifies a life-threatening condition during the PAT assessment, the standardized history can be obtained by the patient’s primary nurse. In infants less than 1 year of age, and especially with neonates, history may be vague, nonspecific, and limited by the parents’ ability to communicate their concern for their child. Past medical history is also important in determining if the child has a prior condition that may affect assessment (e.g., congenital heart disease, chronic respiratory condition, prematurity). The CIAMPEDS mnemonic is a standardized tool that describes components of basic pediatric history (Table 47-1).

| ED, Emergency department. | ||

| C | Chief complaint | Reason for the child’s ED visit and duration of complaint (e.g., fever lasting 2 days). |

| I | Immunizations | Evaluation of the child’s current immunization status: • The completion of all scheduled immunizations for the child’s age must be evaluated. The most current immunization recommendations are published by the American Academy of Pediatrics. • If the child has not received immunization because of religion or cultural beliefs, document this information. |

| Isolation | Evaluation of the child’s exposure to communicable diseases (influenza, chickenpox, shingles, mumps, measles, whooping cough, tuberculosis): • A child with active disease or who is potentially infectious, based on a history of exposure and the disease incubation period, must be placed in respiratory isolation on arrival in the ED. • Immunosuppressed or immunocompromised children can develop active disease even when previously immune. These children must also be protected from inadvertent exposure to viral and bacterial illness while in the ED and placed in protective or reverse isolation. • Other exposures that may be evaluated include exposure to meningitis (with or without evidence of purpura), pneumonia, and scabies. | |

| A | Allergies | Evaluation of the child’s previous allergic or hypersensitivity reactions: • Document reactions to medications, foods, products (e.g., latex), and environmental allergens. The type of reaction must also be documented. |

| M | Medications | Evaluation of the child’s current medication regimen, including prescription and over-the-counter medications: • Dose administered. • Time of last dose. • Duration of medication use. |

| P | Past medical history | A review of the child’s health status, including prior illnesses, injuries, hospitalizations, surgeries, and chronic physical and psychiatric illnesses. Use of alcohol, tobacco, drugs, or other substances of abuse must be evaluated, as appropriate: • The medical history of an infant must include the prenatal and birth history: • Complications during pregnancy or delivery. • Number of days infant remained in hospital post birth. • Infant’s birth weight. • The medical history of the menarcheal female includes the date and description of last menstrual period. |

| Parent’s/caregiver’s impression of the child’s condition | • Identification of the child’s primary caregiver. • Consider cultural differences that may affect the caregiver’s impressions. • Evaluation of the caregiver’s concerns and observations of the child’s condition. Especially significant in evaluating the special needs child. | |

| E | Events surrounding the illness or injury | Evaluation of the onset of the illness or circumstances and mechanism of injury: • Illness: • Length of illness, including date and day of onset and sequence of symptoms. • Exposure to others with similar symptoms. • Treatment provided before ED visit. • Examination by primary care provider. • Injury: • Time and date injury occurred. • M: Mechanism of injury, including the use of protective devices such as seat belts and helmets. • I: Injuries suspected. • V: Vital signs in prehospital environment. • T: Treatment by prehospital providers. • Description of circumstances leading to injury. • Witnessed or unwitnessed. |

| D | Diet | Assessment of the child’s recent oral intake and changes in eating patterns related to the illness or injury: • Changes in eating patterns or fluid intake. • Time of last meal and last fluid intake. • Regular diet: Breast milk, type of formula, solid foods, diet for age, developmental level, and cultural differences. • Special diet or diet restrictions |

| Diapers | Assessment of the child’s urine and stool output: • Frequency of urination over last 24 hours (number of wet diapers); changes in frequency. • Time of last void. • Changes in odor or color of urine. • Last bowel movement; color and consistency of stool. • Change in frequency of bowel movements. | |

| S | Symptoms associated with the illness or injury | Identification of symptoms and progression of symptoms since the onset of the illness or injury event. |

Vital Signs

Obtaining accurate vital sign measurements on children is one of the more challenging aspects of pediatric assessment. Temperature, pulse rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, weight, and pain scores should be obtained on every patient. (See Chapter 12 for further discussion on pain assessment.) Vital signs vary with age (Table 47-2); therefore alterations from normal must be viewed in light of the child’s history and other symptoms. 13 Infants localize infections poorly because of their immature immune system; therefore any child younger than 3 months of age should be evaluated for possible bacterial infection when the child has fever greater than 100.4° F (38.0° C). Temperatures less than 96.8° F (36.5° C) in this age-group can be a sign of infection as well.

| Age | Heart Rate (beats/min) | Respiratory Rate (breaths/min) | Systolic Blood Pressure ( mm Hg) | Weight (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preterm | 120-180 | 55-65 | 40-60 | 2 |

| Term newborn | 90-170 | 40-60 | 52-92 | 3 |

| 1 month | 110-180 | 30-50 | 60-104 | 4 |

| 6 months | 110-180 | 25-35 | 65-125 | 7 |

| 1 year | 80-160 | 20-30 | 70-118 | 10 |

| 2 years | 80-130 | 20-30 | 73-117 | 12 |

| 4 years | 80-120 | 20-30 | 65-117 | 16 |

| 6 years | 75-115 | 18-24 | 76-116 | 20 |

| 8 years | 70-110 | 18-22 | 76-119 | 25 |

| 10 years | 70-110 | 16-20 | 82-122 | 30 |

| 12 years | 60-110 | 16-20 | 84-128 | 40 |

| 14 years | 60-105 | 16-20 | 85-136 | 50 |

Weight can be obtained at triage, but whether at triage or in the patient care area, it needs to be measured near the beginning of the ED visit. Weight is important for calculating medication doses for pediatric patients, and it is in the best interest and safety of the child to have an accurate weight. A length-based resuscitation tape (e.g., Broselow tape) may be used in those situations in which a measured weight cannot be readily obtained. Recording the child’s weight in kilograms reduces the chance of error in medication calculations. Birth weight should be documented for infants younger than 8 weeks of age.

Pulse and respirations can be measured consecutively while the nurse is evaluating airway and breathing. An apical pulse can be obtained with the stethoscope on the child’s chest, and a full minute of respirations can also be counted while the stethoscope is on the chest. Temperatures may be obtained by a variety of routes, including oral, tympanic, temporal artery, axillary, or rectal. The method chosen will depend on the age of the child, medical history of the child, institutional preference, and the needed reliability of the measurement. When an accurate temperature is required to make a treatment decision, a measurement strategy that approaches core temperature is desired—rectal temperature is considered the gold standard.

Obtaining a blood pressure can be a bit more difficult in the younger child. Beginning with the correct size cuff is the first priority. The cuff must cover two thirds of the area being used. 15 A cuff that is too small gives a false high reading, whereas an oversized cuff gives a false low reading. Having a wide variety of cuff sizes is very important when caring for pediatric patients. Using the lower extremity on younger infants and toddlers while distracting them during the procedure is often an alternative way to obtain an accurate blood pressure reading. Manual methods of obtaining blood pressures by auscultation, palpation, or by use of a Doppler are skills that often need to be employed when caring for the pediatric patient. 8. and 13. This is especially true with the critically ill or injured child, but these methods, when practiced, can be easier and faster when used on all children. Noninvasive blood pressure (NIBP) monitor limitations may be due to very low blood pressures that the NIBP is unable to detect accurately. 8 In the pediatric patient, if a low blood pressure is obtained from a NIBP, a manual blood pressure should be obtained to verify. 8 Also if a NIBP is unable to obtain a blood pressure and the child has signs and symptoms suggestive of shock, a manual blood pressure must be attempted. It is not acceptable to document “unable to obtain” simply because the NIBP will not record a blood pressure.

Children With Special Needs

As a result of improvements in health care and technology, children with many different congenital conditions and survivors of life-threatening illness or injury are living to adulthood. 10 Children with special health care needs may present to all levels and types of EDs for treatment related to their underlying disorder or for childhood conditions unrelated to their particular condition. These children can be a challenge to assess and care for, but the same basic principles used for all pediatric patients should be used for this group as well. There are, however, some important points to keep in mind. A basic assessment can be difficult, because cardiopulmonary and neurologic status may be abnormal at baseline. When this is the case, parents or other frequent caregivers are the best source of information about baseline status. Asking the parent or caregiver about vital signs and past medical history specifics is an integral part of the history and assessment. Do not assume you know what the risk factors are for a particular patient or particular congenital condition because often these children are unique. 10 Preexisting problems in many different organ systems can complicate assessment findings and may make it difficult to determine an acute problem. Children with special health care needs may also have less cardiopulmonary reserve than an average pediatric patient. They may not compensate for illness in the same way and can deteriorate more rapidly than most children. 10 The health care provider needs to stay objective when interpreting the assessment findings. Clearly communicating any concerns with the parent and other health care providers on the team is vital.

RESPIRATORY EMERGENCIES

Recognition of respiratory distress and failure in the pediatric patient is crucial because unrecognized or undertreated respiratory compromise is almost always the precursor to cardiac arrest in children. 5. and 13. A child having difficulty breathing can display a variety of symptoms. Upper airway conditions can cause the child to be apprehensive, restless, stridorous, and exhibit intercostal and sternal retractions. Sudden onset of respiratory distress may suggest foreign body obstruction or laryngeal spasms. Airway obstruction in children results from a myriad of causes, including congenital anomalies, peritonsillar abscess, laryngeal obstruction, drug intoxication, and foreign bodies such as coins or toy parts.

Gradual onset of respiratory distress with coughing and an increased work of breathing that could include wheezing, retractions, hypoxia, and nasal flaring is more suggestive of a lower airway problem. 1 Viruses cause 80% to 90% of childhood respiratory infections with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), rhinovirus, parainfluenza, influenza, and adenovirus the most common ones in the pediatric population. An individual virus can cause several different patterns of illness (e.g., RSV can cause bronchiolitis, croup, pneumonia, or the common cold).

Assessment

When a child first arrives in the ED with any respiratory problem, rapid assessment should be completed using a systematic approach with the least-intrusive methods first. Observe the child quickly to obtain vital information on respiratory effort and level of consciousness. Inspect the child’s bare chest for structural abnormalities, symmetry of movement, and use of accessory muscles. Note the child’s position. A child in respiratory distress finds a position of comfort with the body leaning slightly forward and the head in the “sniffing” position, as if smelling a flower; this position allows maximum airway opening.

Respiratory Rate and Pattern

The young child’s respiratory muscles are not well developed, so the diaphragm plays a critical role in breathing. Chest auscultation and observation of rise and fall of the abdomen are the best methods for assessing respiratory rate in patients younger than 2 years. Respiratory rates are often irregular in small children, so the rate should be carefully assessed for 1 full minute.

Normal respiratory rates vary by age. A neonate has a normal respiratory rate from 40 to 60 breaths/min, which slows as the child gets older. With respiratory distress the child’s respiratory rate initially increases. A resting respiratory rate greater than 60 breaths/min is a sign of respiratory distress in a child, regardless of age. As respiratory distress progresses to failure, the child becomes more acidotic, mental status changes occur, and respiratory rate slows. Bradypnea is an ominous sign in a pediatric patient.

Work of Breathing

Children in respiratory distress exhibit increased work of breathing as evidenced by the use of accessory muscles for breathing. As work of breathing increases, intercostal, substernal, and supraclavicular retractions are observed.

Inspiration is an active process in which muscles expand the chest. Exhalation is passive, relying on elastic recoil of the lungs and chest wall. Under normal circumstances these two processes are balanced with expiration roughly the same length as inspiration (inspiration/expiration ratio 1:1). When air passages are narrowed by inflammation or obstruction, time required for inhalation may remain the same with an increase in effort; however, exhalation takes substantially longer than inspiration (inspiration/expiration ratio 1:2 or 1:3).

Alertness, general responsiveness to the environment, and consolability are important observations for assessing mental status with children. Inconsolability is often a sign of hypoxia; however, a restless child who becomes progressively quieter should be carefully assessed to make certain improved oxygenation rather than respiratory failure or exhaustion is causing the restlessness to abate.

Quality of Breathing

Quality of breathing includes depth and sound of breathing. A child’s chest should expand symmetrically; therefore asymmetry or inadequate expansion indicates serious problems such as pneumothorax or hemothorax, foreign body obstruction, or flail chest. To auscultate a child’s chest, place the stethoscope at the anterior axillary line level with the second intercostal space on either side. This helps identify the location of any abnormal breath sounds. The small size of a child’s chest and thinness of the chest wall allow sounds from one side to resonate throughout the thorax (and even into the abdomen). Therefore listening to the anterior and posterior aspects of the chest may not be as useful for pediatric assessment as it is for an adult.

Breath Sounds

Various disorders produce adventitious sounds that are not normally heard over the chest. Stridor is suggestive of an upper airway obstruction. Stridor is usually heard in the inspiratory phase of respiration as the child works to get air past the obstruction. Stridor will be high-pitched in croup, anaphylaxis, and foreign body aspiration. Sounds heard in the expiratory phase suggest lower airway disorders. Crackles result from passage of air through moisture or fluid. Wheezes are produced as air passes through airways narrowed by exudates, inflammation, or spasm. Bilateral wheezing suggests asthma or bronchiolitis, whereas unilateral wheezing suggests foreign body aspiration. Decreased or unequal breath sounds may be suggestive of an airway obstruction, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, or pneumonia.

Grunting is caused by early closure of the glottis during exhalation with active chest wall contraction. It is a forced expiration that creates positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) and prevents airway collapse. Grunting is seen in diseases with diminished lung compliance such as pulmonary edema; it also occurs as a result of pain.

Monitoring

The child with a respiratory problem should be monitored carefully for changes in level of consciousness, work of breathing, and level of fatigue.

Blood gas analysis gives the clearest picture of the patient’s respiratory status. For pediatric patients, a venous or capillary gas sample is easier to obtain than an arterial sample and can provide helpful information on ventilatory and acid-base status. Pulse oximetry is a useful, noninvasive means of continuously measuring the oxygen saturation of hemoglobin in the capillaries and correlates well with arterial blood gas (ABG) measurement. An oxygen saturation of 90% to 93% is the lowest acceptable range in children living at sea level. At higher elevations, saturations that fall into the 88% to 89% range are considered normal. Pulse oximetry’s major limitation is that carbon dioxide and acid-base balance are not evaluated. Many pulse oximeters rely on analysis of hemoglobin color and may not be useful when extremity perfusion is diminished from trauma, cold ambient temperature, or vasopressors or when the number of erythrocytes is decreased, as in anemia. It can be challenging to effectively apply and monitor an infant or small child on a pulse oximeter.

There are several types of probes that can be used, depending on the type of oximeter available. The adhesive type of pediatric or neonatal probe is generally the most useful probe to use with the younger age-group. Common sites of application include the fingers, toes, earlobes, and the bridge of the nose; in infants, flexible probes work through the palm, foot, penis, or arm. 7 Placing the probe on the foot or great toe and then reapplying the child’s sock to limit artifact and lessen the chance the child will remove it can be a very successful approach. In EDs across the country it is becoming more common to see capnography used not only in the intubated patient but in the spontaneously breathing patient as well. In the spontaneously breathing patient it can be used to determine adequacy of ventilation for patients with asthma, patients undergoing procedural sedation, or unconscious patients. 9

Airway Obstruction by Foreign Body

Small children spend a good deal of time exploring their world. Small objects hold a special fascination for children and are likely to end up in their mouths. Foreign body aspiration can occur at any age but is most commonly seen in children younger than 3 years of age. A child brought to the ED with sudden onset of respiratory distress should be evaluated for foreign body aspiration if no other cause is apparent. Initially a foreign body obstruction produces choking, gagging, wheezing, or coughing. If the object becomes lodged in the larynx, the child cannot speak or breathe. If an object is aspirated into the lower airways, there may be an initial episode of choking/gagging followed by an interval of hours, days, or even weeks when the child is without symptoms. Secondary symptoms are related to the anatomic area in which the object is lodged and usually caused by a persistent respiratory infection.

Foreign body obstruction that completely occludes the airway is an acute emergency. Initial treatment is immediate removal of the object using back slaps and chest thrusts for infants less than 1 year of age. For children 1 year or older, abdominal thrusts should be used. Blind finger sweeps are not recommended to relieve upper airway obstruction; however, any visible foreign objects should be removed. Immediate cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy must be performed to open the airway if it remains obstructed. If ventilation appears adequate, allow the child to assume whatever position is most comfortable. Unless the object is observed high in the upper airway, its exact location must be determined by radiograph. Bronchoscopy may be necessary for removal. A swallowed object is allowed to pass normally through the gastrointestinal tract, unless it is long and sharp. Those objects present significant danger of intestinal perforation. Nickel-cadmium batteries must be removed because of the potential for toxic leakage.

Asthma

Asthma is the most common chronic illness in childhood, affecting 5% to 10% of all American children. This chronic lung disease is characterized by hyperreactivity of the airway, bronchospasm, widespread inflammatory changes, and mucous plugging. Wheezing, the most obvious sign of asthma, may range from mild to severe and is accompanied by tachycardia, retractions, and anxiety. Expiration may be prolonged because of narrowed airways. Obtaining a thorough history may be useful in trying to determine the cause and severity of the attack. Repeated asthma attacks are a dangerous sign because of increasing fatigue and potential complications. Recent hospitalization is likely to be an indication of a seriously ill child.

When assessing a child with asthma, evaluate respiratory rate, quality, and effort to determine the degree of respiratory distress; peak flow measurement should be obtained in older children. The child may require supplemental oxygen if saturation on room air is low and tachypnea and tachycardia are present.

Treatment of a child in the ED with moderate to severe distress involves nebulized or metered-dose inhaled β 2-agonist agents (e.g., albuterol and levalbuterol). Nebulized treatments are usually given every 20 minutes for three doses; nebulized anticholinergic agents such as ipratropium (Atrovent) may be added to potentiate the effects of the β2-agonists. Oral systemic corticosteroids are given to suppress and reverse airway inflammation. Adequate hydration for children with asthma is important. They are prone to fluid loss during hyperventilation because of decreased intake due to an increased work of breathing. IV fluids may be necessary for some patients.

Bronchiolitis

Bronchiolitis, a viral infection commonly found in infants younger than 24 months of age, can be a life-threatening illness in high-risk children. Those at high risk include the very young (0 to 3 months of age), premature infants, and children with heart or lung disease or chromosomal abnormalities. The viral infection causes an inflammatory process that produces edema in the bronchial mucosa with resultant expiratory obstruction and air trapping. The virus also causes necrosis of the epithelial cells in the upper airways, which produces thick copious mucus. Bronchiolitis has a broad spectrum of severity. Determination of when the respiratory distress began helps predict the course of the illness because the critical period of bronchiolitis usually occurs during the first 24 to 72 hours after onset of respiratory distress. History typically includes symptoms of a cold, cough, and copious amounts of thick nasal drainage for a few days before onset of respiratory distress. High-risk infants can present with apnea and be very ill in appearance compared to the older child. Hospitalization is necessary for high-risk infants younger than 2 months of age and those with an apneic episode.

RSV, the most common causative organism of bronchiolitis, is a highly contagious respiratory pathogen transmitted by direct contact with infected respiratory secretions or contaminated objects. The virus enters the body by contact of contaminated hands with the nose, eye, or other mucous membranes. Aerosol spread occurs but is less common. Care includes appropriate isolation precautions.

Treatment of bronchiolitis is controversial; bronchodilators and corticosteroids are commonly used, but the efficacy of these treatments has not consistently been shown in studies. 3 Nasal suctioning, oxygen therapy, and adequate hydration along with other appropriate supportive care measures are the mainstays of treatment.

Carbon Monoxide Poisoning

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a colorless, odorless gas resulting from incomplete burning of organic substances, such as gasoline, coal products, tobacco, and building materials. Injury and death occur when CO interferes with or inhibits cellular respiration. CO has a higher affinity for hemoglobin than does oxygen, so when CO enters the bloodstream, it readily combines with hemoglobin to form carboxyhemoglobin, decreasing the amount of oxygen available to be released to the cells. Tissue hypoxia can reach dangerous levels before oxygen is available to meet tissue needs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access