CHAPTER 46. Obstetric Emergencies

Donna L. Mason

Emergency departments (EDs) handle obstetric emergencies throughout all stages of pregnancy. The goal for obstetric emergencies is to stabilize the mother and ultimately prevent any harm to the unborn child or children. Management of obstetric emergencies requires acute assessment skills to identify life-threatening conditions and rapid intervention to prevent adverse outcomes for mother and baby. This chapter describes changes in pathophysiology related to pregnancy, assessment of the pregnant patient, and management of emergencies commonly associated with pregnancy. Refer to Chapter 29 for discussion of obstetric trauma.

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

The female reproductive system consists of the fallopian tubes, ovaries, uterus, vagina, and external genitalia. The cervical os, or opening to the uterus, is located within the vagina. The vagina serves as the exit route for menstrual blood flow, entry point for sperm, and the birth canal. Physiologic activity of the reproductive system is cyclic. Each month the uterus prepares for implantation of a fertilized egg through proliferation of the uterine endometrium. Eggs are stored in the ovaries and released in a cyclic pattern. If the egg is not fertilized, the uterine lining sloughs and is shed as menstrual blood flow. If the egg is fertilized, it begins to reproduce and replicate. The embryo is formed, transported through the fallopian tube, and embedded in the uterine wall to continue its growth.

As the pregnancy progresses, it is characterized by an increasing embryo size and development of various sexual organs. Uterine size increases from about 50 g to about 1100 g. 4 Concurrently, breast size doubles and the vagina enlarges. Total weight gain during pregnancy is about 25 pounds. Other body systems affected by pregnancy include the cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary systems (Table 46-1).

| pCO 2, Pressure of carbon dioxide. | |

| Body System | Changes |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Cardiac output increases 30%-40% by week 27. Placental blood flow is 625-650 mL/min. Blood volume increases by 30%. |

| Respiratory | Heart rate increases throughout pregnancy. Respiratory rate increases. Oxygen consumption increases by 20%. Minute volume increases by 50%. Arterial pCO 2 decreases secondary to hyperventilation. |

| Urinary | Rate of urine formation increases slightly. Sodium, chloride, and water reabsorption increases as much as 50%. Glomerular filtration rate increases about 50%. |

| Gastrointestinal | Smooth muscle relaxes, which increases gastric emptying time. Intestines are relocated to the upper abdomen. |

| Other | Anemia develops because of increased iron requirements by mother and fetus. |

PATIENT ASSESSMENT

Many EDs will provide pregnancy-related care for patients; however, some provide care only for complaints not related to the pregnancy (e.g., colds, flu, sprains, strains, fractures, and lacerations). Each pregnant patient should be carefully assessed and referred to other specialty care as needed (Box 46-1).

Box 46-1

A ssessment G uidelines for the P regnant P atient

Last normal menstrual period

Birth control method

Gravida, parity, and abortion history

Bleeding, discharge, or tissue present

Nausea or vomiting

Urinary symptoms

Abdominal pain—location, duration, description

Estimated date of confinement

Prenatal care

Problems with present or previous pregnancies

Medications and allergies

Maternal medical and surgical history

Blood type and Rh factor if known

Regardless of gestational age, the priorities for assessments for a woman with an obstetric emergency are airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs). The age of fetal viability is considered 24 weeks’ gestation, and though there has been an increased rate of survivability before 24 weeks’ gestation, complications to the preterm infant are greater. Management of obstetric emergencies after onset of fetal viability involves two patients, mother and fetus. See Chapter 47 for discussion of neonatal resuscitation. After assessment of the patient’s ABCs, the next priority is determination of gestational age and evaluation for impending delivery. Specific emergencies are divided into those associated with the first, second, and third trimester and the postpartum period.

FIRST-TRIMESTER EMERGENCIES

First-trimester emergencies involve only one patient—the mother. Mortality is usually related to blood loss. Other issues relate to loss of pregnancy and potential loss of fertility.

Ectopic Pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancies often result from scarring caused by a past infection in the fallopian tubes, surgery on the fallopian tubes, or a previous ectopic pregnancy. Up to 50% of women who have ectopic pregnancies have a past history of inflammation of the fallopian tubes (salpingitis) or pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). 6

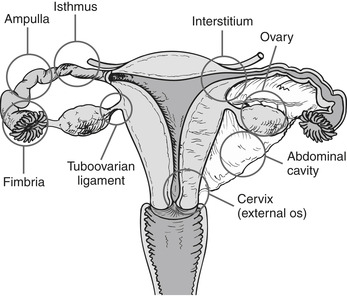

Ectopic pregnancy occurs when the fertilized ovum implants anywhere other than the endometrium, such as in the fallopian tube, ovary, or abdominal cavity. Ninety-five percent of all ectopic pregnancies occur in one of the fallopian tubes, with the most common site for implantation being the ampulla followed by the isthmus (Figure 46-1). The ovum begins to grow but may rupture, usually after the twelfth week of pregnancy. Ectopic pregnancy is one of the major causes of maternal death, usually from hemorrhage.

|

| FIGURE 46-1 Sites of implantation of ectopic pregnancies. Order of frequency of occurrence is ampulla, isthmus, interstitium, fimbria, tuboovarian ligament, ovary, abdominal cavity, and cervix (external os). (From Lewis SL, Heitkemper MM, Dirksen SR et al: Medical-surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinical problems, ed 7, St. Louis, 2007, Mosby.) |

On assessment the patient gives a history of being pregnant, usually about 12 weeks. However, 15% of patients with ectopic pregnancy are symptomatic before the first missed period. Complaints include pelvic pain or vaginal bleeding. Pain, if present, may be mild to severe. If the ectopic pregnancy is leaking or has ruptured, the diaphragm may become irritated from blood in the peritoneum, causing referred pain to the shoulder (Kehr’s sign).

A pregnancy test should be obtained on all women presenting with pelvic pain and vaginal bleeding or spotting. A pelvic examination is done to evaluate the cervical os and identify the amount and source of bleeding. Bimanual pelvic examination defines uterine size and allows for palpation of masses outside the uterus.

If an ectopic pregnancy is suspected, intravenous (IV) access should be established with a large-bore IV catheter in anticipation of potential life-threatening hemorrhage. Quantitative serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin ( β-hCG) level, complete blood count (CBC), and type and screen should be obtained. An ultrasound scan is done to identify an ectopic pregnancy.

Treatment for ectopic pregnancy includes nonoperative and operative interventions. For selected cases, ectopic pregnancy can be medically managed as an alternative to surgery. Methotrexate, a folic acid antagonist that prevents further duplication of fetal cells, is administered intramuscularly, and the patient is followed as an outpatient with serial β-hCG tests. Occasionally β-hCG levels do not fall, so additional methotrexate injections may be necessary. Operative interventions are indicated when the ectopic pregnancy has ruptured, the patient is in shock, or nonoperative interventions are unsuccessful or not appropriate.

In addition to assessment and intervention for physiologic needs, the emergency nurse must recognize the need for emotional support for the patient and the family. The patient may fear for her life and her future childbearing ability, feel concern because the pregnancy is not normal, or experience personal guilt related to the pregnancy.

Abortion

Abortion is defined as any interruption in pregnancy that occurs before the fetus is viable. Fetal viability is usually between 20 and 24 weeks’ gestation or fetal weight of 500 g. This can occur spontaneously as a miscarriage or be artificially induced by chemical, surgical, or other means. 2

Abortion is the number one cause of vaginal bleeding in women of childbearing years, with an estimated 10% to 15% of all pregnancies resulting in spontaneous abortion. 3 This is one of the differential diagnoses for any woman of childbearing years with vaginal bleeding. Table 46-2 summarizes the types of abortion. Causes of abortion include infection, injury, and an incompetent cervix.

| Type | Signs and Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Threatened | Vaginal bleeding Mild abdominal cramping Closed or slightly open os |

| Inevitable | Heavy vaginal bleeding Severe abdominal cramping Open os |

| Incomplete | Heavy vaginal bleeding Abdominal cramping Some products of conception retained |

| Complete | Slight vaginal bleeding No abdominal cramping All products of conception passed |

| Missed | Usually no maternal symptoms Discrepancy in fetal size when compared to dates |

| Septic | Severe abdominal pain High temperature Malodorous vaginal discharge |

The patient presents to the ED complaining of vaginal bleeding with abdominal pain frequently noted. A missed period may or may not be reported. Gynecologic history should be elicited from the patient, including amount of bleeding. Ask the patient how many pads or tampons she has used in the past hour; a general rule of thumb is a saturated pad or tampon equals 5 to 15 mL of blood loss.

Obtain a urine pregnancy test or serum β-hCG level. Palpate the patient’s abdomen for pain or tenderness, which may indicate ectopic pregnancy. A pelvic examination determines the source of bleeding, visualizes any products of conception, and determines dilatation of the cervical os. Observe for vaginal discharge. A bimanual examination is performed to determine the size of the uterus and other reproductive organs, and palpation is performed to determine tenderness. Consider ultrasonography to exclude ectopic pregnancy.

Therapeutic interventions depend on the type of abortion. Fifty percent of threatened abortions result in complete or incomplete abortion within a few hours. A patient with a threatened abortion should be observed closely for changes in hemodynamic status. Document the amount of blood loss. If the patient exhibits signs of shock, replace blood loss with fluids or blood. Provide emotional support to the patient, significant other, and family.

If the abortion is inevitable or incomplete, obtain blood for CBC, Rh type, and type and screen. Start at least one IV line with a large-bore catheter, and administer fluids (normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution). Prepare for suction curettage, which may be performed in the operating room, labor and delivery area, or in some cases, the ED.

If the patient will be discharged, aftercare instructions should include information on bed rest and instructions to return to the ED or call the primary caregiver for increased vaginal bleeding, increasing abdominal pain, passage of tissue, fever, or chills. The patient should also be told to avoid douching and intercourse while on bed rest because these can increase vaginal bleeding, worsen cramping, or cause infection if the cervical os begins to open. The patient should be instructed to follow up with the appropriate referral caregiver. RhoGAM should be given within 72 hours if the mother is Rh negative.

ANTEPARTUM EMERGENCIES

Emergencies that occur during the last months of pregnancy threaten the mother and the fetus. Neurologic sequelae such as seizures and anoxic brain damage are also possible.

Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension

The term pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) refers to toxemia of pregnancy and includes preeclampsia and eclampsia. This condition usually occurs in the last few months of pregnancy (after 20 weeks’ gestation) and can appear up to 2 weeks after delivery. Actual etiology is unknown, though the syndrome occurs most often in women who have a family history of preeclampsia, are primigravida, or are younger than 20 years or older than 40 years of age. There is also increased risk if there is a history of chronic vascular disease, renal disease, diabetes, multiple fetuses, or hydatidiform mole. PIH can cause maternal morbidity and mortality with high fetal mortality.

PIH is characterized by hypertension, proteinuria, and edema. Systolic blood pressure is greater than 140 mm Hg, or there is an increase of 30 mm Hg over the nonpregnant level. An increase of 15 mm Hg of the diastolic over baseline or diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or more is classified as hypertension. 2 Hypertension leads to vasospasm and hemolysis and affects several organ systems.

Blood pressure elevation is the paramount symptom of preeclampsia, and readings are compared to prenatal or early pregnancy blood pressure measurements. Proteinuria is a late sign and is an indicator of severity of the disease. Edema is the least reliable sign because of the normal frequency of occurrence during pregnancy. However, sudden onset of facial edema with weight gain is a significant indicator of preeclampsia (Table 46-3). Pulmonary edema may also be present. Subjective signs of preeclampsia may include visual changes, headaches, epigastric pain, and decreased urination. Preeclampsia left untreated may progress to eclampsia. In eclampsia the patient presents with seizures or coma. This situation is an immediate threat to the mother and fetus.

| Characteristics | Mild Preeclampsia | Severe Preeclampsia |

|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure | Greater than 140/90 mm Hg but less than 160/110 mm Hg 30 mm Hg systolic rise; or 15 mm Hg diastolic rise over baseline readings of early pregnancy (Readings are obtained after rest in a sitting position two times at least 6 hr apart) | Blood pressure greater than 160/110 mm Hg |

| Proteinuria (albuminuria) | 300 mg/L/24 hr or two separate random daytime specimens 6 hr apart (true clean catch) of 1+, 2+ | 5 g or more per 24 hr, 3+, 4+ in true clean-catch or catheterized specimen |

| Edema | Weight gain of more than 3 lbs (1.4 kg) per week or 6 lbs (2.72 kg) per month—any sudden weight gain is suspicious

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|