CHAPTER 44. Dental, Ear, Nose, Throat, and Facial Emergencies

Elizabeth Gaudet Nolan

Most emergencies of the face, mouth, ears, nose, and throat involve discomfort and pain. However, certain conditions can become life threatening if associated edema compromises the airway. Infectious processes in the mouth and face can spread to the brain, with potentially fatal systemic effects. Other concerns include loss of function and possible cosmetic deformities. This chapter describes conditions of the face, mouth, ears, nose, and throat that are frequently seen in the emergency department (ED). A brief review of anatomy is provided. Refer to Chapter 8 for a summary of patient assessment parameters for head, ears, eyes, nose, and throat.

ANATOMY

Structures of the mouth, nose, ears, throat, and face are intimately connected. Injury to one area can affect the others, just as infection from one site can spread to adjacent areas.

Mouth

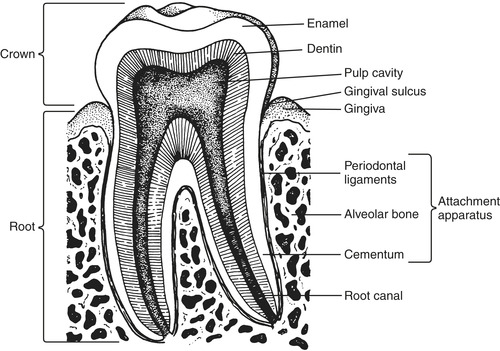

Dentition consists of two main structures: the teeth and periodontium. Teeth comprise pulp, dentin, enamel, and root (Figure 44-1). The pulp, located at the center of the tooth, provides neurovascular supply and produces dentin. Dentin is a microtubular structure that overlays the pulp, provides hydration, and cushions teeth during mastication. Enamel, which covers the crown, is the visible part of the tooth and the hardest substance in the body. The root anchors the tooth into alveolar tissue and bone. The periodontium is made up of gingiva and the attachment apparatus. Gingiva, or gums, is a mucous membrane with supporting fibrous tissue encircling the teeth and covering teeth not yet erupted. The attachment apparatus consists of the cementum, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone. 1 In children, onset of primary and permanent teeth is important in determining management of injuries. 21 Normal primary dentition begins erupting at 6 months, with 20 teeth by age 3 years. Permanent dentition begins at 5 to 6 years with eruption of the first molar and is usually completed by age 16 to 18 for a total of 32 teeth. 1

|

| FIGURE 44-1 Dental anatomic unit and attachment apparatus. (From Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R, editors: Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice, ed 6, St. Louis, 2006, Mosby.) |

Ears

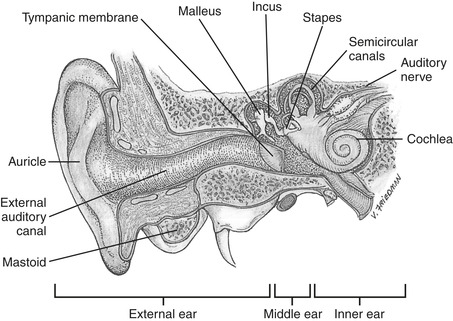

The ear is divided into three sections: external, middle, and inner ear (Figure 44-2). The external ear consists of the auricle (pinna), ear canal, and tympanic membrane (TM). The auricle is a cartilaginous appendage attached to each side of the head that collects and directs sound to sensory organs within the ear. The S-shaped ear canal is approximately 2.5 to 3.0 cm long in adults, terminating at the TM. Glands lining the canal secrete cerumen, a yellow, waxy material that lubricates and protects the ear. 8

|

| FIGURE 44-2 Ear structures. (From Potter PA, Perry AG: Fundamentals of nursing, ed 7, St. Louis, 2009, Mosby.) |

The TM, or eardrum, is a thin, translucent, pearly gray oval disk separating the external ear from the middle ear. It protects the middle ear and conducts sound vibrations to the ossicles. 3 On inspection with an otoscopic light, a cone of light at the anteroinferior aspect of the TM should normally be visible. Another landmark is the long process of the malleus (manubrium) pointing posterior and inferior and terminating in the center of the TM.

The middle ear, an air-filled cavity inside the temporal bone, consists of the ossicles, windows, and eustachian tube. Three tiny ear bones, or ossicles, are the malleus (hammer), incus (anvil), and stapes (stirrup), so named because of their appearance. Round and oval windows open into the inner ear, where sound vibrations enter. The eustachian tubes connect the middle ear with the nasopharynx, allowing passage of air to equalize pressure on either side of the TM. 11 They also provide drainage for middle ear and inner ear secretions into the nasopharynx. The inner ear contains the bony labyrinth, which holds the sensory organs for equilibrium and hearing. 8

Nose

Externally the nose is a triangular, mostly cartilaginous structure that warms, filters, and moistens inhaled air, provides a sense of smell, and is the primary passageway for inhaled air to the lungs. The upper third of the nose where the frontal and maxillary bones form the bridge is bony. Two nares at the base of the triangle allow air to enter and pass into the nasopharynx. The internal nose is formed by the palatine (hard palate) bones inferiorly and superiorly by the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone. Branches of the olfactory nerve pass through the cribriform plate. The nasal cavity is separated by the septum, which forms two anterior vestibules. The septum is usually deviated slightly to one side. Lateral walls are formed by three parallel bony projections—the superior, middle, and inferior turbinates—that help increase surface area to warm inhaled air. 29

Blood supply to the nose originates from the internal and external carotid arteries. The internal maxillary artery branch of the external carotid artery supplies the posterior nasal septum and lateral wall of the nose. As a branch of the internal carotid artery, the anterior ethmoidal artery supplies blood to the anterior septum at Kiesselbach’s plexus in Little’s area. 29 This area is also supplied by the septal branches on the sphenopalatine and superior labial arteries.

Throat

The throat, or pharynx, comprises the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and laryngopharynx. The nasopharynx is positioned behind the nasal cavities and extends to the plane of the soft palate. The pharyngeal tonsils, or adenoids, and eustachian tube openings are located in this area. 22 The oropharynx, a common passageway for both air and food, extends downward from the inferior soft palate to the level of the hyoid bone. The palatine tonsils, lymphoid tissue that filters microorganisms to protect the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts, are found here. The laryngopharynx extends from the hyoid bone to the opening of the larynx anteriorly and esophagus, posteriorly. 24 The pharynx allows passage of air into the larynx. Pharyngeal constrictor muscles propel food or liquid into the esophagus. These muscles are also responsible for the cough and gag reflex, which are controlled by the cranial nerves. The larynx, or voice box, is a tubular, mostly cartilaginous structure that connects the trachea and pharynx; its main purpose is to allow air into the trachea. The epiglottis, a large, leaf-shaped piece of cartilage, lies on top of the larynx. This structure prevents aspiration by forming a lid over the glottis (the space between the vocal cords) so that liquids and food are routed into the esophagus and away from the trachea. 24 The larynx is also responsible for voice production via the vocal cords.

Face

The bony structures of the face are symmetric and consist of a single vomer and mandible and the following pairs of bones: maxillae, palatine, zygomatic, lacrimal, nasal, and inferior nasal conchae. The facial skull forms the shape of the face and provides attachment for muscles that move the jaw and control facial expressions. Cranial nerves V (trigeminal) and VII (facial) are responsible for facial innervation and movement, respectively. The paranasal sinuses are sterile, air-filled pockets situated behind and around the nose, which lighten the weight of the skull, provide resonance for speech, and move secretions into the nasopharynx via ciliated mucous membranes. 8 Four pairs of sinuses are named for their craniofacial location. In children younger than 6 years, the sinuses are not fully developed. 29 The ethmoidal and frontal sinuses are fairly well developed between 6 and 7 years and mature along with the maxillary and sphenoidal sinuses during adolescence. 8

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is the point where the mandible connects to the temporal bone of the skull; it can be palpated bilaterally just anterior to the tragus of the ear. The TMJ is a synovial joint that allows hinge action to open and close the jaws, gliding action for protrusion and retraction, and gliding for side-to-side movement of the lower jaw. 8

DENTAL EMERGENCIES

Dental emergencies affect the teeth and gums. Specific emergencies involve infection, eruption of new teeth, or trauma. The most common emergencies seen in the ED are related to pain. Common causes of dental pain include dry socket, fractured teeth, periodontal disease, erupting teeth, maxillary sinusitis, and post root canal surgery.

Odontalgia

Dental caries are the most frequent cause of dental pain or odontalgia (Figure 44-3). 1 Too much sugar in the diet is largely responsible for decay. Dental caries are also caused by poor oral hygiene, which allows bacterial plaque to develop, which in turn form acids that break down and decalcify tooth enamel. Sodium fluoride, found in toothpaste, oral rinses, and public drinking water, helps stabilize the integrity of tooth enamel to prevent this breakdown. Affected teeth are usually tender to percussion and sensitive to heat, cold, or air. 19 If left untreated, decay progresses and invades dentin and pulp, eventually producing a hyperemic response. The pulp becomes inflamed, leading to pulpitis and finally pulpal necrosis. Occasionally pus leaks from the apex of the affected tooth as a periapical abscess forms. 3 Toothaches accompanied by facial or neck swelling should be assessed and promptly treated to prevent spread of infection. Clinical management includes antibiotics, topical anesthetics, nerve blocks, and analgesics, including parenteral narcotics, as palliative treatment until the patient receives definitive care from the dentist. 2

|

| FIGURE 44-3 Dental caries. (From Grundy JR, Jones JG: A color atlas of clinical operative dentistry crowns and bridges, ed 2, London, 1992, Wolfe Medical Publishing.) |

Tooth Eruption

Between 6 months and 3 years of age, children’s primary teeth erupt, causing a variety of symptoms including pain, irritability, disrupted sleep, nasal discharge, and crying. Increased salivary gland production causes diarrhea, as well as significant drooling. Decreased fluid intake related to dental pain may cause dehydration and low-grade fever of 38.1° C (100.6° F). Care must be taken not to attribute significant fevers to this relatively benign process. Tonsillar or throat infections, thrush, other oral lesions, and respiratory emergencies such as epiglottitis (especially with excessive drooling) should be considered. In the second decade of life, third molars, or wisdom teeth, begin erupting, causing pain in adolescents and adults. Gingival inflammation secondary to wisdom tooth eruption may cause pericoronitis.

Topical anesthetics such as benzocaine are used sparingly to prevent sterile abscess formation. Acetaminophen is useful for analgesia in young children. To maintain hydration, Popsicles are usually well received and also provide pain relief. When there is minimal oral intake, a bolus of intravenous (IV) fluids may be necessary. In adults frequent saline irrigation may be used to remove debris from the affected tooth. Nonnarcotic analgesia is effective for pain relief in adult patients. Any consistent swelling or drainage from the eruption site requires referral to a dentist or oral surgeon.

Pericoronitis

If erupting molars become impacted or crowded, food and debris lodge under the pericoronal flap, causing gingival inflammation or pericoronitis. Pericoronitis is extremely painful, especially with opening and closing of the mouth. Earache on the affected side, sore throat, and fever may also occur. 2 Surrounding tissues appear red and inflamed with submandibular lymphadenopathy and trismus noted in some patients.

Warm saline or peroxide irrigation and mouth rinses are helpful in early stages of pericoronitis. When pus is present, incision and drainage may be necessary. Antibiotic therapy, usually penicillin or erythromycin, is indicated. Follow-up with an oral-maxillofacial surgeon within 24 to 48 hours for removal of the affected third molar is highly recommended. 1

Fractured Tooth

The most frequently seen dental emergency in the ED is a chipped or broken tooth, usually anterior maxillary teeth. Trauma to dentition occurs as a result of sports activity, motor vehicle collisions, propulsive objects, falls, convulsive seizures, and physical assaults or abuse. With children, it should be noted that 50% of physical trauma in child abuse occurs in the head and neck region. 18 The emergency nurse should assess for concurrent head injury or maxillofacial trauma. Aspiration of a tooth or fragment or an embedded tooth should also be considered.

Management of fractures of the anterior teeth is determined by the relationship of the fracture to the pulp as well as patient age. 1 The Ellis classification system is used to describe location of tooth fractures. Class I fractures are the most common, involving only enamel. Injured areas appear chalky white. Cosmetic restoration is possible with dental referral within 24 to 48 hours. Class II fractures pass through the enamel and expose dentin. The fracture area appears ivory-yellow. Fractures are urgent for children because there is little dentin to protect pulp. Bacteria pass easily into pulp, causing an infection or abscess if exposed for longer than 6 hours. 21 Adults may be treated up to 24 hours later because the pulp is protected by a thicker layer of dentin, which reduces potential for infection. Place warm, moist cotton covered by dry gauze over the exposed area as needed for discomfort secondary to thermal sensitivity. Class III fractures are a dental emergency (Figure 44-4). Injury to the enamel, dentin, and pulp cause a pink or bloody tinge to the fractured area. Exposure of pulp also exposes the nerve, causing significant discomfort. Again, dry gauze can be used to minimize discomfort from thermal sensitivity. Some practitioners apply a layer of zinc oxide or calcium hydroxide to exposed dentin, which is then covered with dental foil. 17 The patient should be referred to a dentist with follow-up within 24 hours. Oral analgesics or a nerve block are usually effective for pain control. Tetanus immunizations should be administered as appropriate. Reassure the patient that cosmetic restoration is possible with enamel-bonding plastic materials. 2

|

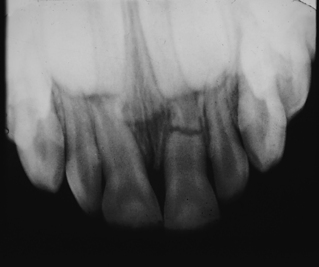

| FIGURE 44-4 This radiograph reveals a root fracture in the apical third of an upper primary incisor. This was suspected clinically because of tenderness and increased mobility. (From Zitelli B, Davis H: Atlas of pediatric physical diagnosis, ed 3, St. Louis, 1997, Mosby.) |

With facial trauma, assess the airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs) before assessing the dental problem. History should include mechanism of injury, concomitant injuries, and tissue loss. Consider abuse in children, older adults, or disabled adults when the history does not correlate to the injury. Assess for tooth pain, thermal sensitivity, stability of the tooth in the socket, and malocclusion. Complications of tooth fractures include infection (pulpitis), malocclusion, embedded tooth fragments, aspiration of tooth fragments, color change, or loss of affected teeth.

Tooth Avulsion

Tooth avulsion is a dental emergency. When a tooth has been torn from the socket, tissue hypoxia develops, followed by eventual necrosis of the pulp. 16 Reimplantation within 30 minutes greatly increases chances for reimplantation and healing. The periodontal ligament cells die if the tooth is out of the socket for more than 60 minutes. Determine the mechanism and time of injury immediately on arrival. Handle the avulsed tooth by the crown to avoid damage to attached periodontal ligament fragments. These fragments aid in healing of the reimplanted tooth. 21 Ideally the tooth should be rinsed and placed back in the socket as soon as possible. Immediate reimplantation is not always possible because of lack of patient cooperation, life-threatening injuries, or other factors at the scene of injury. In these cases the tooth should be transported in Hank’s solution (pH-preserving fluid), milk, saline, or under the tongue of an alert patient. Use discretion with children, who may swallow or aspirate the tooth. Primary teeth (6 months to 6 years) are not reimplanted because fusion with the bone interferes with permanent tooth eruption and can cause cosmetic deformities. 1 If the tooth cannot be found, examine the oral cavity and face to ensure the tooth is not embedded in soft tissue. A chest x-ray examination is recommended to rule out tooth aspiration.

Symptoms include pain and bleeding at the site of the avulsion. Assess for concomitant head, neck, or maxillofacial injuries. Moist saline gauze may be applied to exposed oral tissues for comfort and to control bleeding. Administer analgesics and tetanus prophylaxis as indicated. Instruct the patient not to bite into anything with the affected tooth and to avoid hot or cold substances. Referral to a dentist or oral surgeon for definitive care is recommended.

Dental Abscess

Primary dental abscesses are periapical and periodontal. Periapical abscesses occur as an extension of pulpal necroses from a decayed tooth or traumatic injury. A pocket of plaque and food debris between the tooth and the gingiva causes localized swelling at the apex of the tooth, which leads to periodontal abscess formation. 18 Normally abscesses are confined; however, certain infectious processes can spread to facial planes of the head and neck. 1 The upper half of the face is affected with extension of infection from the maxillary teeth. Cellulitis in the lower half of the face and neck extends from the infection of the mandibular teeth. 1 With localized abscesses the patient may have severe pain unrelieved by analgesics, fever, malaise, foul breath odor, and slight facial swelling near the affected tooth. An extensive abscess causes facial and neck edema, trismus, dysphagia, difficulty handling secretions, and potential airway obstruction.

Oral or parenteral narcotics, antipyretics, and antibiotics such as penicillin or erythromycin are recommended. 7 If abscess fluctuance is present, incision and drainage with culture and sensitivity of the exudate are required. The patient should be instructed to take medications as directed, use warm saline rinses, and follow up with an oral surgeon, dentist, or ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist within 24 to 48 hours for definitive care. Admission for further diagnostic studies and IV antibiotics may be necessary if the patient has abnormal vital signs or is unable to take oral medications. 18

Gingivitis

Gingivitis, or inflammation of the gums, is usually caused by poor dental hygiene, allowing for the accumulation of food debris and plaque in crevices between the gums and teeth. This periodontal disease, along with periodontitis (loss of supporting bony structure of the teeth) affects approximately two thirds of young adults and 80% of middle-age and older adults. It is the most common cause of tooth loss today. 2 Gingivitis may also occur with vitamin C deficiency or in pregnancy and puberty because of changing hormone levels. 8 If inflammation continues, alveolar bone is lost, leading to periodontitis and eventual loss of teeth. Visual evidence of gingivitis includes red, swollen gum margins and possible bleeding. Pain unrelieved by over-the-counter analgesics, difficulty chewing, and low-grade fever also occur. Topical anesthetics, analgesics, and oral antibiotic therapy are indicated. Patient teaching regarding good oral hygiene, including brushing and flossing 3 to 4 times a day with peroxide and warm water rinses every hour, is extremely important to prevent extension of gingivitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access