Care of Patients During Disasters, Bioterrorism Attacks, and Pandemic Infections

Objectives

1. Analyze differences between an emergency situation and a disaster.

2. Discuss an emergency preparedness plan for a health care facility.

3. Compare the stages of psychological response that occur with a disaster.

5. Identify responsibilities and duties of the nurse in the care of disaster victims.

6. Explain safety measures to be employed for a chemical emergency.

7. Demonstrate knowledge of measures to be taken in the event of a nuclear disaster.

8. Explain warning signs that suggest a bioterrorism attack has occurred.

10. Synthesize the importance of debriefing of health care personnel after a disaster.

1. Participate in a disaster drill.

2. Teach a group of adults how to prepare safe water after a disaster has disrupted the water supply.

Key Terms

bioterrorism (p. 1010)

debriefing (p. 1016)

decontamination (dē-kŏn-tăm-ĭ-NĀ-shŭn, p. 1009)

disaster (p. 997)

mass casualty (p. 999)

pandemic (p. 1015)

surge capacity (p. 1000)

triage (TRĒ-ăhzh, p. 999)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

Disaster Preparedness and Response

An extraordinary event, such as a multivictim incident involving an explosion or a train crash, requires a rapid and skilled response to manage the wounded. There may be walking wounded, critically wounded, and fatally wounded victims. This type of event usually can be handled by the community’s emergency medical services and the hospital emergency departments.

A disaster exists when the number of casualties exceeds the resource capabilities of the area; thus the community’s existing emergency resources may be overwhelmed. Natural disasters include epidemics, earthquakes, explosions, hurricanes, tornadoes, fires, and floods. Intentional terrorist attacks or accidental man-made disasters may result from transportation incidents or events involving chemical, biologic, or nuclear materials. A disaster causes mass casualties, psychological as well as physical trauma, and permanent changes within the community.

The governmental agencies for disaster planning are the Department of Homeland Security, the Office of Domestic Preparedness, and the U.S. Public Health Service. The American Red Cross is a voluntary organization that traditionally provides the basic essentials of shelter, food, and first aid during a natural disaster (Figure 44-1). In most communities, the local Office of Emergency Services (OES), the Red Cross, and the Salvation Army work together to formulate disaster plans. They coordinate their services with each other and with other agencies in planning for essential services, such as shelter, transportation, communication, and welfare. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has a website with information on all types of disasters, weather events, and mass casualty events.

Special courses in civil defense and disaster nursing are usually offered by the OES, the Red Cross, and professional organizations. These courses help nurses and volunteer workers to understand the function and coordination of agencies involved in a particular type of disaster. To increase availability of volunteer health care professionals, registries such as the Emergency Systems for Advance Registration of Volunteer Health Professionals (ESAR-VHP) have been designed to proactively verify credentials, provide disaster response training, and coordinate deployment of professionals in conjunction with local, state, and national response plans. Such programs are intended to avoid the chaos of disaster and the underutilization of skilled volunteers (Peterson, 2006).

Whether the disaster is natural or related to war, it will involve physical injuries, loss of property, and interruption of the normal activities of daily living. People often will need food, clothing, shelter, medical and nursing or hospital care, and other basic necessities of life.

Disaster supplies, with all the recommended items, should be prepared by every household.

Every family should have a contact person out of the geographic area where extended family members can call to receive information about the welfare of their relatives. Communication into and out of the disaster region is often cut off. Each member of a family living together should know whom they are to call if separated from one another.

Most people know about these recommendations, but few are truly prepared. In fact, one of the barriers of disaster preparedness, at all levels, is an underlying belief that “it probably won’t affect me” (Legg, 2009). At the system level, disaster events are viewed as “low risk” with “high impact” (Ahmad, 2009); thus administrators may be reluctant to divert time, money, and attention to disaster preparedness when health care systems are strained by the daily workload. All nurses must encourage people in the community to prepare. You should proactively (take it upon yourself to) seek out disaster training at your work setting and advocate for sufficient emergency supplies and support.

Community Preparedness

The law enforcement agency, the city or county emergency management department, and the state public health department are responsible for coordinating efforts to assist people when a disaster happens. The American Red Cross may disperse personnel and supplies to assist with essential needs and medical care. If the state requests assistance, Homeland Security determines if the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is to be called. If so, FEMA brings personnel and aid to the area. If a disaster is of major proportions, a Disaster Medical Assistance Team (DMAT) may be activated at the state or federal level. These units bring medical, paraprofessional, and support personnel along with medical equipment and supplies to sustain an operation for a minimum of 72 hours. The team provides triage (sorting out of casualties by priority of need for treatment), evacuation, primary health care, and assistance to local health care facilities that are overwhelmed. The emergency management team sets up a communications system, and the emergency medical services (EMS) personnel at the scene notify the emergency departments at the hospitals of the situation. With pagers, telephone trees, and instant computer alert messages, essential personnel are notified of a disaster or mass casualty (many-victims incident).

Community residents are instructed about what to do in the event that an earthquake, wildfire, hurricane, tornado, or flood occurs in their area.

If advised to evacuate the area, residents should gather essential belongings, medications, pets, and keepsakes and leave immediately. If tornado sirens are sounded, people should take refuge in a basement or in an inner room without windows, such as a closet or a bathroom, to avoid flying debris. Getting into the bathtub and covering oneself with cushions or a mattress can also protect a person from flying debris. If outside, it is best to lie in a culvert or ditch below ground level.

Hospital Preparedness

The Joint Commission requires that hospitals have an emergency preparedness plan in place. There are guidelines for emergency preparedness by type of facility. Emergency department physicians undergo formal training for disaster events. Emergency department nurses are encouraged to obtain certification in emergency preparedness. Health care systems must self-evaluate surge capacity, which is defined as the maximum services that a facility can offer when every resource is mobilized (Barishansky & Langan, 2009); therefore the emergency plan should be tested with drills at least twice a year.

The emergency preparedness plan will identify who will be in charge and the chain of command for the facility. The designated communications officer is responsible for internal communication, such as keeping the staff informed, and for external communication, such as contacting other agencies for help, or reporting data about infection or chemical contamination that could have widespread effects (Rebmann, 2009).  There will be a hospital incident commander (physician or administrator) who assumes responsibility for launching the emergency preparedness plan. This person’s role as commander is to view the entire situation, to bring in needed human and supply resources, and facilitate the flow of patients through the system. Usual hospital routine will be altered to accommodate care for high numbers of patients. Departmental roles will be changed. Physical therapy and other departments may close down usual operations and become the minor treatment area for the nonurgent patients. The concept of “reverse triage” or sending relatively stable patients home can be used to free up beds. Using an evidence-based computer model, researchers determined that any patient who had a 12% or less risk for an adverse event within the next 4 days could be discharged under disaster circumstances (Kelen et al., 2009).

There will be a hospital incident commander (physician or administrator) who assumes responsibility for launching the emergency preparedness plan. This person’s role as commander is to view the entire situation, to bring in needed human and supply resources, and facilitate the flow of patients through the system. Usual hospital routine will be altered to accommodate care for high numbers of patients. Departmental roles will be changed. Physical therapy and other departments may close down usual operations and become the minor treatment area for the nonurgent patients. The concept of “reverse triage” or sending relatively stable patients home can be used to free up beds. Using an evidence-based computer model, researchers determined that any patient who had a 12% or less risk for an adverse event within the next 4 days could be discharged under disaster circumstances (Kelen et al., 2009).

A medical command physician will focus on determining the number, acuity, and medical needs of the casualties arriving from the scene of the disaster. This person will organize the emergency health care team response to the injured or ill patients. Specialists trained for the particular type of disaster will be called in to help as the need is foreseen. Decisions will be made about who is to be evacuated to a facility with a higher level of care.

A triage officer, usually a physician, with the assistance of triage nurses, will rapidly evaluate each patient at the hospital and send the patient to the appropriate area for immediate or eventual treatment. The emergency department supervisor or charge nurse collaborates with the medical command physician and triage officer to organize nursing and ancillary personnel to meet patient needs. A telephone tree will be activated to call in off-duty staff. In addition to these personnel, there will be a supply officer, communications officer, infection control officer, and public information officer. The public information officer will manage the media. Hospital staff, at all levels, will be called on to assist with whatever care is needed. Long-term care facilities may need to evacuate residents, or they may need to take in people from other facilities or the community.

Psychological Responses to Disaster

Any intense event results in an emotional response. Natural disasters or massive injuries from a man-made event have both physical and emotional effects. The phrase “they are in shock” is used to explain the emotional state of the victims following one of these events. Although emotions can trigger physical signs and symptoms, the condition is usually not life threatening unless the individual affected has a preexisting condition that puts her at risk.

Signs and symptoms of emotional shock include headaches, nausea, and chest pain. Preexisting medical conditions may worsen due to the stress. Remaining calm and seeing to immediate physical needs can reassure the victim that someone is in charge that has control over the situation. Severe emotional trauma, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, may take years of therapy to process.

Following a major disaster, psychological events occur in stages (Crisis Management Consultants, 2010):

Triage

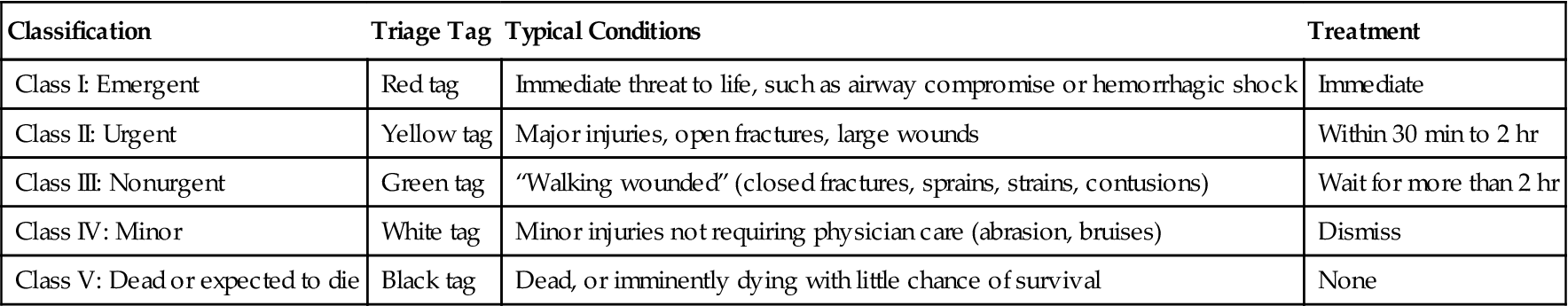

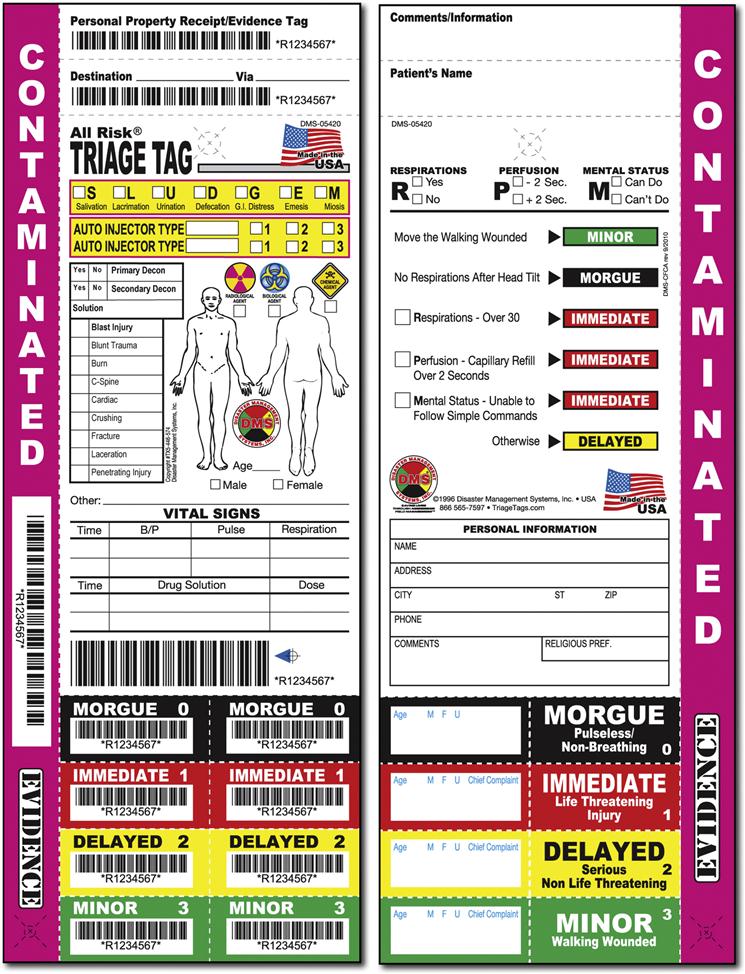

After a disaster, care of victims is prioritized according to a triage system that is different from regular emergency department triage (Table 44-1). Those victims with life-threatening conditions and a good chance of survival are cared for first. When there are more victims of a disaster than medical personnel to treat them, those who are likely to survive are treated first; these patients are given red, yellow, or green tags (some classification systems may also include a white tag). The mortally wounded and those who are not expected to survive are attended later, and these patients are issued a black tag (Figure 44-2). The choice of issuing tags is difficult for most nurses, but in a disaster, the good of many must prevail over benefit to the few.

Table 44-1

| Classification | Triage Tag | Typical Conditions | Treatment |

| Class I: Emergent | Red tag | Immediate threat to life, such as airway compromise or hemorrhagic shock | Immediate |

| Class II: Urgent | Yellow tag | Major injuries, open fractures, large wounds | Within 30 min to 2 hr |

| Class III: Nonurgent | Green tag | “Walking wounded” (closed fractures, sprains, strains, contusions) | Wait for more than 2 hr |

| Class IV: Minor | White tag | Minor injuries not requiring physician care (abrasion, bruises) | Dismiss |

| Class V: Dead or expected to die | Black tag | Dead, or imminently dying with little chance of survival | None |

Stoppler, M.C. (2007). Medical triage: code tags and triage terminology. Medicinenet.com. Available at www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=79529.

Even though triage may have been done in the field, triage is performed again at the emergency care facility. Green-tagged patients usually comprise the greatest number in large-scale disasters. Patients need to be managed until they are able to be treated. If not managed, patients can become a health hazard by walking around with infection, radioactivity, or chemical contamination. A special bracelet with a disaster number may be applied to tagged patients.

Nursing Roles and Responsibilities During Disaster

Your basic nursing skills will serve you well if you are called on to work under disaster conditions; for example, you could be asked to:

• Perform emergency nursing measures.

• Evaluate the environmental and physical risks and shortages (e.g., no electrical power).

Other responsibilities require specialized knowledge that is not part of a nurse’s routine daily job. You must study this material now and review it periodically before a disaster happens.

• Be prepared for self-survival (i.e., stock your own household with emergency supplies).

• Know the disaster plan for your workplace and identify your duties accordingly.

• Know the meaning of warning signals of disaster and the action to be taken.

• Know measures for protection against radioactive, chemical, or biologic contamination.

• Know the community disaster plans and community health resources.

During emergency care, you will perform needed procedures such as inserting catheters, nasogastric tubes, and possibly intravenous (IV) lines and drawing blood. In many types of disasters outside the hospital you may need to improvise because of lack of equipment. Basic principles of nursing apply in a disaster, but adaptation to “crisis standards” is necessary if there is a disparity between need and availability of equipment, supplies, or personnel. You may be called on to exercise leadership and judgment in determining the condition of each victim, using supplies and equipment, and detecting changes in the environment that might be hazardous. Performing nursing procedures in a disaster situation demands skill and judgment to provide for the good of the greatest number of people. You may be asked to help cook, serve food, pass out water, or do whatever else is a priority need at the time. Proactive development and understanding of crisis standards, to include an ethics committee, is recommended (Rebmann, 2009).

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends that nurses be skilled in the following areas if they are to be involved in providing health care during a disaster:

Observing, recording, and reporting information about patients to appropriate authorities must be done in an organized manner. General physical and mental conditions of patients and signs and symptoms that may indicate change in condition must be quickly identified. During a disaster, preventing the spread of infection is a primary nursing concern. Table 44-2 identifies the communicable diseases that can become epidemic after a disaster. Infection control is a top priority when large groups of people are together in a shelter because the incidence of communicable disease is much greater. Although the National Patient Safety Goal is intended for the prevention of health care–related infections under normal circumstances, hand hygiene has an even greater potential as a basic infection control measure to protect large groups of people that may gather together after a disaster.

Table 44-2

Communicable Diseases with Epidemic Potential (All Except Tetanus) in Natural Disasters

| Disease | Transmission | Agent | Clinical Features | Incubation Period | Diagnosis | Treatment | Prevention/Control |

| Waterborne | |||||||

| Cholera | Fecal/oral, contaminated water or food | Vibrio cholerae serogroups O1 or O139 | Profuse watery diarrhea, vomiting | 2 hr-5 days | Direct microscopic observation of V. cholerae in stool | Intensive rehydration therapy; antimicrobials based on sensitivity testing | Hand hygiene, proper handling of water/food and sewage disposal |

| Leptospirosis | Fecal/oral, contaminated water | Leptospira species | Sudden-onset fever, headache, chills, vomiting, severe myalgia | 2-28 days | Leptospira-specific IgM serologic assay | Penicillin, amoxicillin, doxycycline, erythromycin, cephalosporins | Avoid entering contaminated water; safe water source |

| Hepatitis | Fecal/oral, contaminated water or food | Hepatitis A and E viruses | Jaundice, abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, fever, fatigue, and loss of appetite | 15-50 days | Serologic assay detecting anti-HAV or anti-HEV IgM antibodies | Supportive care; hospitalization and barrier nursing for severe cases; close monitoring of pregnant women | Hand hygiene, proper handling of water/food and sewage disposal; hepatitis A vaccine |

| Bacillary dysentery | Fecal/oral, contaminated water or food | Shigella dysenteriae type 1 | Malaise, fever, vomiting, blood and mucus in stool | 12-96 hr | Suspect if bloody diarrhea; confirmation requires isolation of organism from stool | Nalidixic acid, ampicillin; hospitalization of seriously ill or malnourished; rehydration | Hand hygiene, proper handling of water/food and sewage disposal |

| Typhoid fever | Fecal/oral, contaminated water or food | Salmonella typhi | Sustained fever, headache, constipation | 1-3 days | Culture from blood, bone marrow, bowel fluids; rapid antibody tests | Ampicillin, co-trimoxazole, ciprofloxacin | Hand hygiene, proper handling of water/food and sewage disposal; mass vaccination in some settings |

| Acute Respiratory | |||||||

| Pneumonia | Person to person by airborne respiratory droplets | Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, or viral | Cough, difficulty breathing, rapid breathing | 1-3 days | Clinical presentation; culture respiratory secretions | Co-trimoxazole, chloramphenicol, ampicillin | Isolation; proper nutrition; if cause is Streptococcus, polyvalent vaccine to high-risk populations |

| Direct Contact | |||||||

| Measles | Person to person by airborne respiratory droplets | Measles virus (Morbillivirus) | Rash, high fever, cough, runny nose, red and watery eyes; serious postmeasles complications (5%-10% of cases)—diarrhea, pneumonia, croup | 10-12 days | Generally made by clinical observation | Supportive care; proper nutrition and hydration; vitamin A; control fever; antimicrobials in complicated cases with pneumonia, dysentery; treat conjunctivitis, keratitis | Rapid mass vaccination within 72 hr of initial case report (priority to high-risk groups if limited supply); vitamin A in children 6 mo–5 yr of age to prevent complications and reduce mortality risk |

| Bacterial meningitis (meningococcal meningitis) | Person to person by airborne respiratory droplets | Neisseria meningitides serogroups A, C, W135 | Sudden-onset fever, rash, neck stiffness; altered consciousness; bulging fontanel in patients less than one year | 10-12 days | Examination of CSF—elevated WBC count, protein; gram-negative diplococci | Penicillin, chloramphenicol, ampicillin, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, co-trimoxazole; supportive therapy; diazepam for seizures | Rapid mass vaccination |

| Wound-Related | |||||||

| Tetanus | Soil | Clostridium tetani | Difficulty swallowing, lockjaw, muscle rigidity, spasms | 2-10 days | Entirely clinical | Tetanus immune globulin | Thorough wound cleansing, tetanus vaccine |

| Vector-Borne | |||||||

| Malaria | Mosquito (Anopheles species) | Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax | Fever, chills, sweats, head and body aches, nausea and vomiting | 7-30 days | Parasites on blood smear observed using a microscope; rapid diagnostic assays if available | Chloroquine, sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine | Mosquito control; insecticide-treated nets, bedding, clothing |

| Dengue fever | Mosquito (Aedes aegypti) | Dengue virus-1, -2, -3, -4 (Flavivirus) | Sudden-onset severe flulike illness, high fever, severe headache, pain behind the eyes, and rash | 4-7 days | Serum antibody testing with ELISA or rapid dot-blot technique | Intensive supportive therapy | Mosquito control; insecticide-treated nets, bedding, clothing |

| Japanese encephalitis | Mosquito (Culex species) | Japanese encephalitis virus (Flavivirus) | Quick-onset, headache, high fever, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, tremors | 5-15 days | Serologic assay for JE virus IgM-specific antibodies in CSF or blood (acute phase) | Intensive supportive therapy | Mosquito control, isolation of cases, mass vaccination |

| Yellow fever | Mosquito (Aedes, Haemogogus) | Yellow fever virus (Flavivirus) | Fever, backache, headache, nausea, vomiting; toxic phase—jaundice, abdominal pain, kidney failure | 3-6 days | Serologic assay for yellow fever virus antibodies | Intensive supportive therapy | Mosquito control, isolation of cases, mass vaccination |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree