CHAPTER 42. Female Genital Mutilation

Patricia A. Crane

Denouncing the practice of female genital mutilation (FGM) can make some countries feel superior and self-righteous, but it certainly does not solve the problem. Our purpose should not be to criticize and condemn. Nor can we remain passive, in the name of some bland version of multiculturalism. We know that the practice of genital mutilation is painful and can have dire consequences on the health of the baby girl and, later on, of the woman. But we must always work from the assumption that human behaviors and cultural values, however senseless or destructive they may appear to us from our particular personal and cultural standpoints, have meaning and fulfill a function for those who practice them. People will change their behavior only when they themselves perceive the new practices proposed as meaningful and functional as the old ones. Therefore, what we must aim for is to convince people, including women, that they can give up a specific practice without giving up meaningful aspects of their own cultures.

—Statement of the Director General to the World Health Organization’s Global Commission on Women’s Health (WHO, 1996)

The clinical forensic role is found applicable in many professional positions where the nurse faces intersecting ethical challenges, cultural issues, and legal matters affecting the provision of healthcare. One of the newest crimes of interpersonal violence to confront nursing, female genital mutilation or female circumcision (FGM/FC), is achieving great international notoriety in political, human rights, and women’s reproductive health research in the United States, Canada, and other countries to which women migrate. In the face of unfamiliar and often inhumane acts that may be confronted on a daily basis, the forensic responsibility must be integrated into the nursing process. Integral to professional practice is the ability to honor individual human rights and to maintain professional and legal objectivity, as well as cultural sensitivity and respect for patients.

An overview of the history of FGM/FC, its psychological and physical health consequences, and the possible legal ramifications will provide a background for the development of appropriate assessment, diagnosis, and intervention. Case studies support the need for cultural competence and patient education, while accessible resources are available throughout the nursing process for follow-up and referral of patients and families for evaluation. With the combination of cultural competence and forensic knowledge to the application of the nursing process, enhanced patient outcomes are assured.

Significance of the Issue

Worldwide, more than 130 million women and ultimately their families are affected by the practice of FGM/FC. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2000) admittedly underestimates that nearly 2 million more are subjected to the ritual annually with prevalence rates ranging from 18% (Tanzania) to 97% (Egypt) in African countries (Muteshi & Sass, 2005). The age at which a young woman undergoes FGM/FC varies greatly but may be from sometime in the first year of life up to 18 years old. In villages and communities with limited access, the person performing the ritual procedure may travel through the area every four to five years, so girls in a wide age range are expected and often forced by peers and parents to undergo the procedure. According to the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH, 1997), the rural population is not as likely to support FGM as are the employed and educated women. In larger cities, a ritual practitioner may be available for hire on a daily basis. For others, a celebration and feast takes place after a season of superfluous crops and is associated with fertility. The village elder decides which group of marriageable girls will participate in an associated FGM ritual (Hosken, 1981), and it has been reported that the younger the girls are, the better. Smaller girls are easier to restrain when cut and are less likely to remember the pain and terror. Girls may be more verbally and physically rebellious as they get older and have more education regarding the FGM practice and the harm it may cause.

Large university surveys of students in Khartoum, Sudan, report that more than half are mutilated. It seems promising for the future generations that 88% of the women and 78% of the men want the practice to be abolished (Herieka & Dhar, 2003).

Early estimates stated that more than 168,000 people from countries where FGM is practiced had entered the United States by 1997, either as immigrants or as refugees. Within this group, those who may be at risk for FGM/FC are under the age of 18 and number more than 60,000 (E. T. Ortiz, personal communication, January 30, 1997). Bringing the tradition with them, indigenes are leaving their countries of origin for new opportunities in various countries throughout Europe, Canada, and South America. In the United States, large pockets of FGM/FC-practicing populations are settling together in communities in major metropolitan areas such as Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., Dallas, Denver, New York, and Boston. Hence, health personnel and educators who face the issue on a daily basis may have little or no knowledge of how to initiate conversation regarding the problem or how to control their reaction when it comes up in a medical interview or examination. Recent data assessing the healthcare professionals’ awareness classifications and definitions of FGM/FC showed that almost all had experience with examining women and knew the definition of FGM/FC. However, they knew little about the laws and could not classify the type of FGM/FC, and only half of them had the necessary knowledge for medical management (Zaidi, Khalil, Roberts, & Browne, 2007).

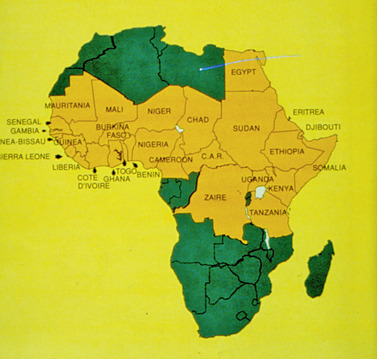

Girls are subjected to the inhumane tradition of FGM/FC across all continents. Although the practice is not mandatory or supported by Islam, Christian, or Judaic law, it is found to be performed and encouraged at various times in history by members of all religions. Hosken’s (1981) extensive investigation on worldwide genital cutting resulted in reports, with few actual medical studies, of such ancient practices being found in South America, Mexico, Europe, Australia, Asia, India, and primarily in Africa. Genital mutilation is not unknown in the United States. In the 1950s, such procedures were documented as a treatment for control of women with hysteria and sexual problems. Medical reports and statistics indicate that FGM/FC is utilized, with varying degrees of severity, primarily across the central belt of Africa in more than 28 countries (Fig. 42-1) and a few isolated groups in Asia and the Middle East (WHO, 2000). They follow local indigenous religious customs and Islamic law. However, Muslim leaders are adamantly opposed to references to FGM/FC as a religious practice. In fact, they are sought out and used in the movement to eradicate FGM/FC in Africa and in the United States because of their highly influential roles as teacher and authority.

Criminalization of FGM/FC

Congress amended the U.S. Code as part of the Illegal Immigration and Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, by adding “whoever knowingly circumcises, excises, or infibulates the whole or any part of the labia majora or labia minora or clitoris of another person who has not attained the age of 18 years shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 5 years, or both.” The Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) in cooperation with the Department of State is required to inform aliens who are issued visas when they enter the United States of the severe harm of FGM. The information must be presented in a manner that is limited to the practice and respectul of the cultural values of the societies that practice FGM. Most importantly the information must explain that there are legal consequences for performing or subjecting a child to FGM under the criminal or child protection statutes or as a form of child abuse (Center for Reproductive Rights, 2004). The Center for Reproductive Law & Policy (1997) claims that no one has been convicted based on the laws but cases based on the statutes have been brought before the courts.

Sixteen states in the United States have developed laws criminalizing the practice of FGM addressing the issue in a manner similar to the federal legislation, by prohibiting the practice of FGM and instituting criminal sanctions (Center for Reproductive Rights, 2004). Other states consider child abuse law adequate to guarantee protection of individual human rights of a child.

Criminalizing the offense in the United States can have drastic effects on noncitizens depending on the judge, the skill of the attorney, and the extent of their knowledge of immigration law (Brady & Tooby, 1997). For many authorities, little is known about the practice of FGM and its health implications, despite its emergence in the United States. Adverse consequences, such as deportation even without a conviction, are possible, with no consideration for the person’s length of residency. Persons participating in the perpetration of the crime in the United States can be faced with fines and jail sentences but must also consider their personal value of keeping the family together and the survival outcomes for the family members who may be left behind should deportation or incarceration occur. Brady and Tooby also strongly advise contacting an immigration organization and experts in immigration law to best meet the needs of clients who are not citizens.

Hundreds of young women, after being educated and given the choice, seek to escape their country of origin and inhumane rituals, often seeking asylum in Europe, Canada, or the United States. The asylum standard in the United States requires three elements: (1) persecution, (2) a well-founded fear, and (3) an act of persecution that was based on the grounds of race, religion, nationality, or membership in a particular social group. Despite the need for education, ultimately a decision on the matter would rest with the asylum officer or immigration judge. Asylum law is in need of reform and may not offer much in the way of protection for a woman (Stern, 1997). There may be detrimental effects on a woman’s physical and psychological health, yet being granted asylum may be impossible or take years. However, case summaries of gender asylum clearly show that increasing numbers of immigrant women from many different countries are succeeding in being granted asylum.

On a global perspective, the international health community has addressed the practice through many forums for at least half a century. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1959, the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child in 1990, the UN Declaration on Violence Against Women in 1993, the UN High Commission on Refugees Statement Against Gender-Based Violence in 1996, to name a few, express opposition to the practice and strongly encourage enforcement of the law in countries where it is forbidden. The International Council of Nurses’ position statement (1992) advises that nurses pay particular attention to protecting children from all forms of abuse so they can grow up in health and dignity. Human rights are essential to quality of life, regardless of ethnicity or sex. Many feel that outlawing FGM/FC in other countries was a move to please the advocates in the Western world whose voice and money have influence. Family or community decisions to cease a ritual practice that is deeply rooted and of incalculable value are not likely to be made based on foreign policy alone, although this may carry weight in the long run. Laws in the European Community and Canada have resulted in arrests that have gained international notoriety but resulted in little change in FGM-practicing countries. In Egypt there is evidence that the practice of FGM/FC appears to be in decline following passage of the prohibition laws six years ago, but the decline is thought to be related to multimedia education and publicized deaths of young women (Hassanin, Saleh, Bedaiwy, Peterson, & Badaiwy, 2008). The shift in public opinion, public denouncement of the practice, and its decline will continue as parents see that other parents have stopped the practice.

Educational awareness of the health complications and educational programs appear to be effective prevention in Kenya with a noteworthy decline in FGM/FC. The law passed in 2001, and although this is a positive step, it may deter women from seeking medical assistance for complications from FGM/FC (Livermore, Monteiro & Rymer, 2007). Researchers in Nigeria, following a health education intervention, documented a statistically significant increase in the number of adults who wanted to stop FGM/FC and in those who do not want their daughters mutilated. It is not known if the intervenion and postive attitude changes will lead to actual behavioral changes (Asekun-Olarinmoye & Amusan, 2008). Placing FGM elimination within a comprehensive development strategy that envelops reproductive and gender issues may be most effective. Also the health education must be accompanied by skill building if behavior changes are desired when complex cultural issues are deep rooted (Asekun-Olarinmoye & Amusan, 2008).

In the United States, as with other crimes of violence, many feel that making the act illegal could drive it underground where it will flourish, shrouded in secrecy. There are reports from immigrant groups in California that circumcision is being surreptitiously performed on immigrant girls. In personal conversations with young African immigrant working mothers, they relay fears that family members or babysitters, perceiving that the practice is still of social value and a necessary cultural tradition, may locate an individual with little medical training to perform circumcisions. Returning from work to find the baby mutilated is a constant fear. As documented in the University of California Hastings gender asylum case summaries (2000), the fear that young daughters will be taken and circumcised is prevalent in mothers who try to leave this ritual behind. On the other hand, wealthy families may send their daughters on “holiday” to be circumcised (Reichert, 1998).

Historical Basis

Ritual ceremonies that involve the cutting of women’s genitalia are rooted in tradition thousands of years old. As with many cultural practices, the original rationale is recondite. Documented history is lacking with much of women’s health behavior, such as birthing and circumcision rituals. However, the reasons most often given for FGM/FC were of a psychosexual, sociological, or hygienic nature (Gibeau, 1998). Passed down through generations of oral history, there is no foundation for rationalizing such practices today.

Some say eliminating a woman’s sexual desire reduces any undue sexual demands of her husband, who may have several wives to enhance his progeny and wealth. In addition, destruction of the clitoral nerve endings would prevent her from seeking sexual pleasure with other men. The clitoris was also seen as masculinizing and the rumor was that it would grow very large and turn a woman into a man unless it was removed when she was young. To others the clitoris is thought to be poisonous to the man or to the newborn, and those who were to touch it would die.

Hygienic reasons required that the clitoris and labia be removed to make the woman clean and beautiful. Closing the vagina ensures virginity and a high bride price, critical issues in an area where families may depend on the price of daughters and cattle to keep the family subsistent. Not only can the surgery keep her virginal before marriage, if the man is away for long periods of time hunting, trading, and protecting herds of grazing animals, a woman may have the vagina resutured, reinfibulation, to assure her virtue in his absence and prevent rape.

If originally instituted for any or all of these stated reasons, the most often quoted reason for FGM/FC in recent times is that it is simply the tradition. Previously, no man would think of marrying a woman who had not been cut (Hosken, 1993). Female relatives consider that it is something they must do to maintain their daughters’ marriageability, family status, and honor. It is not felt to be mutilation.

Naming the Ritual

What to call the procedure varies from international conferences to meetings of policy makers. Unequivocally, in healthcare and policy settings, the WHO terminology of female genital mutilation is accepted. Admittedly, the reason the surgery takes place is not to mutilate one’s daughter. To insinuate the idea is insulting to the ancestors and sets up an impenetrable barrier in communication between patient and provider. However, mutilation is often the end result. In the country of origin, those who practice the procedure may refer to it as being made clean, being cut, or excision. Others refer to it as circumcision, and it is linked with premarital celebrations and coming-of-age rituals at the time of adolescence. In reality, there is little resemblance to the circumcision of males, which refers to the foreskin of the penis being removed. An Arabic word, sunna, meaning tradition, is the only word known for FGM/FC in some countries. In personal communication, a physician said that if she used any other word the women would not know what she was saying. The WHO has developed descriptions of four categories of FGM/FC: Type I, Type II, Type III, and Type IV (WHO, 2000).

Type I

Type I may include removal of the prepuce or hood of the clitoris and partial or total removal of the clitoris. This is typically the procedure known as sunna.

Type II

Type II may be known as excision and includes removal of the clitoris and labia minora. The vagina is typically not covered, but copious scar tissue and adhesions may obliterate the vaginal introitus over time.

Type III

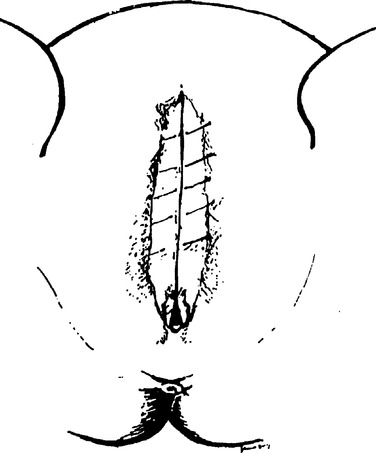

Type III, also known as infibulation or pharaonic circumcision, includes removal of the clitoris, labia minora, and part of the labia majora. The two sides of the remaining vulvar tissue are closed over the vagina in a crude fashion, often with suture or acacia thorns. A small hollow reed from a local plant may be left in place while the injury is healing. This allows for a small opening to be left for the passage of urine and menstrual flow. The girls’ legs may be bound together for several weeks. It is not uncommon for the incision to require opening at the time of marriage or childbirth. Many women request that they be resutured afterward, as local practice and the woman’s family may dictate.

Type IV

Type IV is an unclassified grouping of all other mutilations of the female genital area such as pricking, piercing, cutting, and scraping of vaginal tissue, incisions to the clitoris and vagina, and burning, scarring, or cauterizing of tissue. (See Fig. 42-2, Fig. 42-3 and Fig. 42-4.)

|

| Fig. 42-2 |

Physical Consequences

Despite often noted horrific outcomes, many variables influence the severity of scarring and damage to the genital area after cutting, backed by little scientific evidence (Morison, Scherf, Ekpo, et al., 2001). In areas where the trend is toward medicalization, the educated, trained professionals perform procedures with proper surgical technique using up-to-date sterile equipment so there is less risk. Medicalization is not the norm, and FGM/FC is still against the law and a punishable criminal act. As the severity of cutting increases, so do the gynecological and obstetrical problems (Jones, Diop, Askew, et al., 1999).

Data-based research is emerging and is more powerful than anecdotal cases. One study in Egypt (n = 264) was comprised of 75% circumcised rural women and the rest were urban, educated, noncircumcised women (Elnashar & Abdelhady, 2007). The researchers noted statisically significant greater amounts of dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, loss of libido, failure of orgasm, husband disatisfaction, vaginal tears with childbirth, episiotomy, and distressed babies with circumcised women. Mental problems such as somatization, anxiety, and phobia were significant in circumcised women as well (Elnashar & Abdelhady, 2007).

Often the village midwife, traditional birth attendant (TBA), local barber, or a male or female circumciser performs the procedure. Routinely, these are not highly educated people, and they have little or no knowledge of anatomy, asepsis, disinfectant, or medications and rarely use anesthesia. They may have a reputation throughout the region and have learned to earn a living in this manner through several generations of women. Local educators often provide circumcisers with less primitive equipment as well as education on asepsis in an attempt to curb some of the problems.

Despite the use of applications of local herbs, animal products, and primitive closure of the vagina with thorns, hemostasis may not be accomplished, resulting in hemorrhage as well as an irreversible state of anemia. Immediate physical problems include shock, not only from hemorrhage but also from severe pain resulting from the tragic degree of sensory nerve damage, an irreversible condition. If the circumciser is using items such as a rusty razor, sharp stone, shell, piece of glass, machete, or scissors, it is not difficult to comprehend frequent and widespread infections. Tetanus may be fatal in many cases and risks of exposure to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), various forms of hepatitis, and other pathogens are greater when instruments are used on a group of girls without cleaning, which is often the case. Damage to surrounding organs and lack of knowledge of nerves and arteries in the genital area end in tragic results, including gangrene. Urinary retention can occur with the blockage of the urinary opening with eventual irreversible kidney damage. Urinary tract infections can be immediate or occur more frequently the rest of a woman’s life. Over the long term, damage to the urethra from the cutting, frequent infections, and growth of scar tissue undoubtedly cause chronic pain, urinary hesitancy, and incontinence. Women and girls often report that it takes 10 to 15 minutes to complete urination. The bartholin gland openings near the vaginal introitus may be covered with scar tissue, a blockage that can lead to cysts, abscesses, and tumors in the vulvar area up to 10 cm in diameter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access