CHAPTER 41. Sexual Deviant Behavior and Crimes

Anil Aggrawal

Forensic nurses, especially those working in the psychiatric field, will continue to work with sexual offenders and deviants. This chapter highlights some salient features of sexual offenders and how forensic nurses can best cooperate with medical and legal personnel for the psychiatric assessment and evaluation, treatment, and legal commitments relating to these offenders.

Who Is a Sexual Offender?

Contrary to popular belief, sexual offenses and deviant behaviors are not a product of modern civilization. Both sexual offenses and deviant behaviors have been mentioned in ancient books such as the Holy Bible (Aggrawal, 2009b). Sexual offender is a term that is still in search of a universally acceptable definition. Plainly put, a sex offender is one who offends sexually. However, sexual behaviors within a group or community are greatly influenced by prevailing sociocultural norms. A behavior that may offend one person, group, or culture may not offend another, because it may be the norm in that culture. For instance, in some cultures, shaking hands with a female might be regarded as grossly inappropriate behavior, if not a downright sexual offense. In other cultures, shaking hands—even social kissing—may be considered quite appropriate. A sexually explicit behavior is also not necessarily a product of advanced civilization. In some primitive tribes of Africa, going topless for females is a norm, whereas if a woman walked topless on the streets of New Delhi or New York, she would almost certainly be arrested as a sexual offender (Aggrawal, 2009a). In addition, norms within a particular community may change over time.

One would imagine that sexual acts that are construed almost universally as loathsome or harmful behaviors may be agreed on as sexual offenses by all societies, but even this is not true. The case of rape—forcible sexual intercourse against the will of the other party—illustrates this point. Among the Hmong tribe of Laos, where marriage by bride capture is a continuing cultural practice, rape under certain circumstances is perfectly legal. This practice continues even among Hmong communities that have migrated to the United States and has even given them the so-called “cultural defense” against allegations of rape.

Marriage by bride capture is a practice whereby a man abducts a woman he likes and holds her captive for three days. During this time, he repeatedly rapes her. After the third day, the girl is freed and given a choice to either reject or marry him. In practice, however, the girl always ends up marrying her abductor, either willingly or under her parents’ pressure. Rape, at least under these circumstances, thus is a perfectly legal activity among the Hmongs. In one highly publicized case (1985), Kong Moua, a male member of the Hmong community in America, kidnapped Seng Xiong, a female member of his own community, and had repeated sexual intercourse with her. Moua genuinely believed he was following Hmong customary marriage practices. After she was set free, Xiong not only rejected the marriage-by-capture tradition but filed kidnapping and rape charges against Moua. Moua sought “cultural defense.” Allowing the defense, the judge asked Moua to plead guilty to one misdemeanor count of false imprisonment and sentenced him to just 120 days in jail and a mere $1000 fine (Aggrawal, 2007).

Sex crime, sexual offense, and sexual offender are terms that have no universal meanings. In broad and general terms, however, a sex crime sex crime definition of is a sexually explicit behavior that is illegal in a given jurisdiction. It has been determined to be a criminal act because it exploits, caters to, makes possible, or is dependent on explicit sexual behavior (MacNamara & Sagarin, 1977). A useful definition of sex offenders was offered in 1965 by the Kinsey group: “A sex offender sex offender definition of is a person who has been legally convicted as a result of an overt act, committed by him for his own immediate sexual gratification, which is contrary to the prevailing sexual mores of the society in which he lives and/or is legally punishable” (Gebhard, Pomeroy, & Christenson 1967). Definitions provided by most workers are similar or simple modifications of this one. Some authors include specific crimes, such as pedophilia or incest, within this general definition, signifying, perhaps, a personal weight given by them to a specific sex crime. Glass (2004), for instance, includes pedophilia in the previous definition, and in her modified definition states that a sex offender is “someone who has committed or attempted to commit any type of illegal or nonconsensual sexual act and/or any sexual behavior involving children under the legal age of consent, based upon the laws governing the location where the sexual behavior occurred (p. 222).”

Another term that appears frequently in discussions of sexual offenses is sexual violence. Sexual violence, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), refers to “any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed, against a person’s sexuality using coercion (i.e., psychological intimidation, physical force, or threats of harm), by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting, including but not limited to home and work” (NSVRC, 2004, p. 4).

Sexual offenses have been committed in virtually every condition and setting. More recently, sexual offenses in a military environment, the so-called military sexual trauma (MST), has been making headlines both in the lay press and in academic publications (David and Simpson, 2006, Himmelfarb and Yaeger, 2006, Kelly and Vogt, 2008, Kimerling and Gima, 2007, Kimerling and Street, 2008, O’Brien and Gaher, 2008, Regan and Wilhoite, 2007, Valente and Wight, 2007, Suris and Lind, 2008 and Yaeger and Himmelfarb, 2006)

What Is Deviant Behavior?

Sexually deviant behaviors are more commonly known among medical parlance as paraphilias. Just as there can be no universal definition of a sexual offender, there cannot be a universally accepted definition of sexually deviant behavior. The case of homosexuality perhaps demonstrates this best. Homosexuality, even between two consenting adults, is considered a sexually deviant behavior in many societies. But in several other societies, it is legally acceptable. Even within the same communities, the behavior has been viewed differently at different times. In Ancient Greece, homosexual behavior was not considered abnormal and was even considered to be more elevated and spiritual than heterosexual relationships. As time passed, however, it gradually began to be considered a sexual perversion and even a criminal behavior. Until 1968, homosexuality was listed as a sexual deviation in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 1968). However, during the next decade, it began to be considered normal sexual behavior and finally in 1980, it was removed from DSM-III (Lamberg, 1998). It is, however, not considered an exalted form of sexual relationship yet.

Other sexual behaviors, such as fellatio, cunnilingus, anal sex, prostitution, and some categories of visual and literary erotica and pornography, which were once considered sexually deviant behaviors, have been decriminalized in many societies and are tolerated relatively better than in other societies. Sexually deviant behavior, or paraphilia paraphilia as a social concept, may thus be conceived more as a social rather than a medical concept. There is, however, a core of extremely deviant behavior (say lust murder) that has always been, and perhaps always will be, considered abnormal.

From a biomedical point of view, paraphilias have been defined explicitly in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, fourth edition, revised ( DSM-IV-TR) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). It specifically mentions 15 paraphilias by name. Of these, eight have been allotted specific diagnostic codes (Table 41-1).

| 302.2 | Pedophilia |

| 302.3 | Transvestic fetishism |

| 302.4 | Exhibitionism |

| 302.81 | Fetishism |

| 302.82 | Voyeurism |

| 302.83 | Sexual masochism |

| 302.84 | Sexual sadism |

| 302.89 | Frotteurism |

| 302.9 | Paraphilia not otherwise specified |

Seven other paraphilias—telephone scatologia (obscene phone calls), necrophilia (sexual attraction to corpses), partialism (exclusive focus on part of body), zoophilia (sexual attraction to animals), coprophilia (erotic attraction to feces), klismaphilia (erotic attraction to enemas), and urophilia (erotic attraction to urine)—are grouped in the category “Paraphilia not otherwise specified.” It is specifically stated that these are examples, but this category is not limited to these.

Etiology of Sexually Deviant Behavior

Several theories have been advanced regarding the etiology of sexually deviant behavior. Some of the most common ones are discussed next.

Psychodynamic theory

According to the psychodynamic theory of the mind, human psyche is composed of three primary elements: the id, which is guided by the pleasure principle; the superego, the rational component of human psyche, which controls the id to a great extent; and the ego. Sexual deviancy occurs when the id is overactive. This theory appears to have a strong clinical foundation as well, especially as successful treatments have been based on this theory (Lohse & Hauch, 1983).

Biological theory

According to this theory, sexually deviant behavior can be explained by abnormal sex hormone levels (Saleh & Berlin, 2003), testosterone levels (Studer, Aylwin, et al., 2005), and even chromosomal makeup (Wiedeking, Lake, et al., 1977). This theory also has a sound clinical basis, especially as antiandrogens (e.g., leuprolide acetate) seem to have a corrective effect on sexually deviant behavior (Bancroft et al., 1974, Berlin, 1988, Briken and Berner, 2000, Buvat and Lemaire, 1996, Cooper, 1986, Cooper and Ismail, 1972, Gagne, 1981, Kravitz and Haywood, 1995, Kravitz and Haywood, 1996, Krueger and Kaplan, 2001, Rosler and Witztum, 1998, Rousseau and Couture, 1990, Thibaut and Cordier, 1993, Thibaut and Cordier, 1996 and Thibaut and Kuhn, 1998).

Feminist theory

Feminists tend to explain sexually deviant behavior, especially rape, from a cultural, historical, and even political context. Rape is explained as men’s tendency to oppress women. According to this theory, psychodynamic and biological factors do not play a part in sexual offending. Sexual offending results merely from men’s desire to suppress women (Drieschner & Lange, 1999).

Attachment theory

According to this theory, all humans love to establish strong emotional bonds with others. An individual who has experienced some loss or emotional distress may act out abnormally because of loneliness and isolation.

Behavioral theory

Initially developed by Pavlov, behavioral theory tends to explain all behaviors in terms of rewards or punishments. A behavior that is rewarded tends to become a habit, whereas a behavior that is punished becomes extinct. Sexually deviant behavior is rewarded by the sexual pleasure that the culprit enjoys. If the behavior is not punished (say, if the culprit is not apprehended), it is not extinguished. Thus, a sexual deviant who remains free will tend to repeat the sexual behavior. Behavioral theory, on its own, is unable to completely explain such complex behavior as sexual deviancy.

Cognitive-behavioral theory

This theory takes into account cognitive factors too. If the offender does not have feelings of guilt or shame or rationalizes them through excuses and justifications, the sexually offending behavior is enforced.

Psychosocial theory

Psychosocial theory, initially propounded by Erikson, conceived child development occurring as a series of fixed, predetermined stages. This model extends Freud’s psychoanalytical theory by focusing on the child’s emotional development. According to this theory, deviant sexual behavior may be viewed as a response to external social factors.

Integrated theory

This theory tends to integrate all previous theories. It takes into account elements such as motivations to offend, rationalization of behavior, diminishing of internal barriers, and various external social factors.

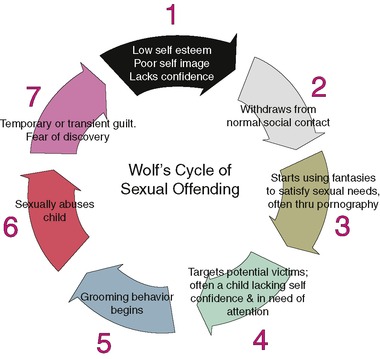

Cycle of Sexual Offending

The term cycle is used in two senses in the literature on sexual exploitation. The first sense refers to the theory of generational cycle, whereby some people who are sexually abused as children go on to become abusers themselves. This theory has been challenged because, whereas clinical evidence supports the view that some abusers were abused themselves as children, it cannot account for the gender imbalance in female victims and male perpetrators. There are far more female victims than female perpetrators of sexual crimes, and if all or even most of the female victims were to become sexual offenders, the gender imbalance would not be as much. The second sense of the term cycle refers to a behavioral cycle, sometimes also known as Wolf’s cycle of offending (Wolf, 1984). This cycle refers to a self-reinforcing sequence of sex offender behavior (Fig. 41-1).

|

| Fig. 41-1 |

Wolf’s model was initially applied to pedophile offending and later was developed for work with adolescents. Sexual offenders are often people whose self-esteem is low and who expect rejection from others. Often they have poor social skills. Some may have experienced some kind of emotional trauma in their lives, such as a divorce, a bereavement, or a redundancy, which may leave them feeling bad about themselves. As a result, these people can withdraw from others, thus becoming emotionally isolated.

Not all people from this group become sexual offenders. Those who are likely to offend sexually tend to compensate for their isolation, low esteem, and personal unhappiness by developing relationships with children, which may lead to sexual offending.

For sexual offending to take place, the potential culprits have to first overcome their “internal inhibitions.” They have to convince themselves that what they want to do is not wrong. They must quiet their conscience and persuade themselves that no harm will be done if they engage in the sexually offending behavior. This occurs through a process called cognitive distortion.

The next stage consists of identifying a target child. Often, the child will be vulnerable in some way. For instance, the child may have a low self-esteem and may be looking for attention. Initial fantasies about the child may be reinforced by using pornography, perhaps using the Internet. Internet chat rooms may also be used to find a child.

Now the stage comes to overcome the external inhibitions. These include the child’s parents, the society, and the child’s own resistance. To break the child’s resistance, the perpetrator engages in the grooming process, a way of gaining the child’s trust (Table 41-2). The perpetrator may lure the child with chocolates, toys, or by simply paying attention to him or her to make the child feel special (Lang & Frenzel, 1988). The child thrives on this attention and becomes attracted to the perpetrator.

Be nice to the child. Take the child for rides on motorcycle or snowmobile. Give the child money. Get into playful horseplay and wrestling around. Take off their clothes during horseplay. Play Nintendo together. Sleep in the same room and climb on top of the child’s body and act as if asleep. Play house. Buy toys and candy. Sleep with the child. Give the child piggyback rides or invite lap-sitting. Appear to be hugging, but thinking sexual thoughts. Pretend to be interested in toys of the child. Be kind and then become more than a friend. Spend free time with the child and discover their special interests. Exhibit porn magazines to the child. |

The perpetrator may now tell the child that sexual activity is a way for them to show their love for each other. If the child is aroused, the perpetrator may say that the child must want the activity to continue and may suggest that the child will enjoy the sexual relationship.

Following the abuse, the child often feels confused, guilty, ashamed, betrayed, lost, and afraid. The perpetrator may quiet the child with bribery or threats. Any initial guilt a perpetrator experiences will lead to further lowering of self-esteem and the cycle starts all over again.

An understanding of this cycle is vital for law enforcement authorities and for personnel engaged in treating sexual offenders. The cycle has to be broken by increasing the self-esteem of perpetrators. Law enforcement authorities may look with suspicion at any person who is a loner and whose house is full of chocolates, candies, and toys.

Female Sexual Offenders

The term female sexual offender may sound like an oxymoron to many, especially as females, usually considered the weaker sex, are seen as victims rather than as perpetrators of sexual abuse. However, recent crime reports and academic papers are fairly consistent in showing that the number of females who commit sexual offenses is not trivial (Oliver, 2007). According to a 1999 Bureau of Justice Statistics report, between 1993 and 1997, 2.2% of offenders arrested for forcible rape each year were female. This amounts to roughly 10,000 female sexual offenders being arrested each year in the United States alone (Greenfeld, Snell, et al., 1999).

Among the female sex offenders, mothers are also involved. By interviewing them in depth, Denov (2004) derived data from a small sample of 14 adult victims (7 men, 7 women) of child sexual abuse by females. Most respondents reported severe sexual abuse by their mothers. It might also intuitively appear that female-perpetrated sexual abuse may be relatively harmless as compared to sexual abuse by men. However, in Denov’s study, a vast majority of victims reported that the experience of female-perpetrated sexual abuse was harmful and damaging. Both male and female victims reported long-term difficulties with substance abuse, self-injury, suicide, depression, rage, strained relationships with women, self-concept and identity issues, and a discomfort with sex.

More recently, Peter has compared male- and female-perpetrated sexual abuse in terms of victim and abuser characteristics, type of abuse, family structure, and worker information, and has shown a prevalence rate of 10.7% for female-perpetrated sexual abuse (Peter, 2008). According to this study, girls were more likely to be victimized for both male- and female-perpetrated sexual violence. Also females tended to abuse younger children. The majority of children came from families with lower socioeconomic status although one in five victims of female-perpetrated sexual abuse came from middle-class homes. Also, when females abused, referrals to child welfare agencies were more likely to be made by nonprofessionals.

Assessment of Sexual Offenders

The assessment of risk for criminal recidivism (reoffending) among sex offenders is a task of great concern to the judicial system, the correctional services, and society at large. Data from the United States Bureau of Justice Statistics (Langan, Schmitt, et al., 2003) show that 5% of about 10,000 sex offenders who were released from prison in 1994 were rearrested for a sex crime within three years. More recently, a review of 61 studies (n = 23,393) demonstrated that the sexual offense recidivism rate was 13.4% (Hanson & Bussiere, 1998). There were, however, subgroups of offenders who recidivated at higher rates. Sexual recidivism rates of up to 42% have been reported (Hagan, Anderson, et al., 2008).

The assessments of sexual offenders aid in making several crucial decisions about these individuals. These include sentencing, prison classification, parole, and whether these individuals should be restrained (in some kind of treatment facilities) after their sentences are over (conditional release).

The enactment of “sexual predator” laws with regard to the long-term incapacitation of high-risk sex offenders after serving their criminal sentences have further increased the need for such assessments. Furthermore, limited monetary and professional resources have created a need for assessment tools that are simple in nature and sound with regard to their accuracy in identifying offenders with risk of reoffending.

There is now a legal necessity of such assessments too. Case law and legislation, on a number of occasions ( Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California, 1976; Macintosh v. Milano, 1979), have charged mental health professionals with the responsibility of identifying potentially violent patients and protecting the public from them. Several jurisdictions have codified such clinician responsibility (Weinberger, Sreenivasan, et al., 1998).

Risk factors

Several key variables—the risk factors—are known to increase the likelihood of committing an offense. These variables are subdivided into static and dynamic factors. Static factors are historical and unchangeable, whereas dynamic factors are current and changeable. Static factors include age at first offense, history of prior convictions, gender, type of victim, and motivation for committing past crimes. Dynamic factors include present economic situation, marital status, attitudes supportive of crime, faulty cognitions, sexually deviant preference, family condition, leisure activities, criminal friends, substance abuse, and employment status. Most assessment tools seek to uncover and quantify these risk factors.

Tools for assessment

Predicting how an individual will behave in the future is a difficult—if not impossible—task. Yet clinicians entrusted with the assessment of sexual offenders must make this prediction fairly accurately. It is now known that sexual offense recidivism can be predicted to a certain extent by measures of sexual deviancy (e.g., deviant sexual preferences, prior sexual offenses) and, to a lesser extent, by general criminological factors (e.g., age, total prior offenses).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access