Chapter 4 Thromboembolic disorders

INTRODUCTION

Thromboembolic disorders are the leading cause of direct maternal death in the UK (Lewis & Drife 2004).

From 2000–2002, 30 women died from thrombosis and/or embolism in the UK. Some 25 deaths were as a result of a pulmonary embolism and five from cerebral vein thrombosis. Ofthe deaths from pulmonary embolism, four deaths occurred in pregnancy, one in labour and 17 postnatally. Some 16 of these women had riskfactors for thromboembolic disorders. In 57% of all cases, there was evidence of substandardcare. Prophylactic anticoagulants are strongly recommended in all areas of healthcare where mobility is limited and this must be a consideration in the care of women undergoing childbirth dependent on risk (RCOG 2004). The majority of thromboembolic events during the childbearing process are not fatal, but may be responsible for considerable long-term morbidity (Gates 2000).

RELEVANT ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

The control and role of blood pressure in the movement of blood through the circulatory system has already been explained (seeCh. 2). The continued brisk movement of blood through blood vessels is one of the factors that prevents coagulation and thrombosis. Control of the coagulation cascade is another.

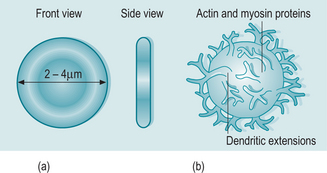

The remaining 45% of blood is composed of blood cells:

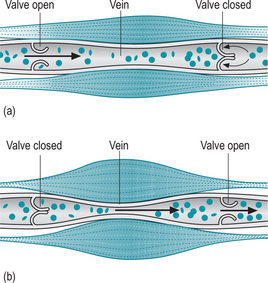

Movement of blood through the circulation is controlled primarily by contraction of the heart. Blood pressure exerted by this process and by the constraining influence of the walls of the blood vessels moves blood rapidly through the arterial network. Blood pressure gradually drops as blood vessels become narrower, and once blood has passed through the capillary network, pressure is comparatively low. Additionally gravity plays a role (seeCh. 2). Venous return of blood to the heart is therefore more easily disrupted and it is in the venous system that there is increased risk of the formation of a thrombus particularly in lower limbs.

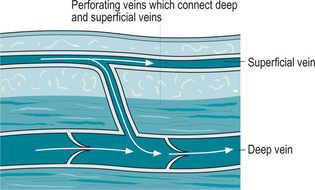

The venous system of the lower limbs consists of three distinct types of vein; deep veins which lie within the skeletal muscles (femoral, tibial and popliteal); superficial veins which lie outside this sheath (long and short saphenous veins); and joining the two systems, perforating or communicating veins (Fig. 4.2).

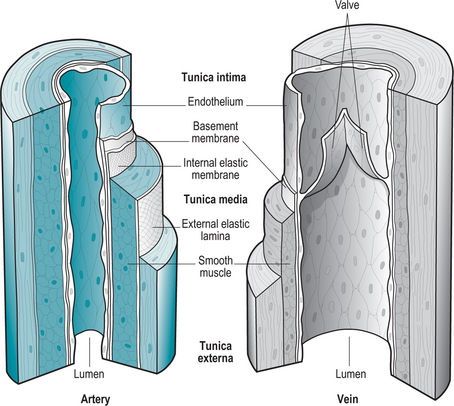

Valves are folds of the tunica intima which lines the veins (Fig. 4.3). The tunica intima is a very thin layer consisting of the basement membrane and endothelium. Valves can thus be easily damaged by injury to the blood vessels. In some individuals, valves are inherently incompetent and the upward flow is more difficult to maintain.

Venous return depends therefore on several factors:

Haemostasis (cessation of bleeding)

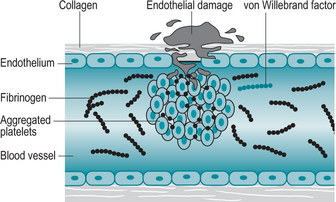

Blood is essential to life. It is imperative that any loss of this substance due to trauma of a bloodvessel is corrected as quickly as possible. The body has a range of measures it can bring into play to seal the blood vessel and minimize blood loss (Fig. 4.5).

Initially, on detecting a damaged blood vessel, thrombocytes release serotonin which, along with other chemicals released by the damaged cells, causes local vasoconstriction of the blood vessel to minimize blood loss. Around the site of the trauma, thrombocytes clump together and release substances such as ADP, which attract many more platelets to the area, adding to the size of the temporary plug formed (Walthall 2006). Coagulation of blood occurs around the plug forming a permanent clot.

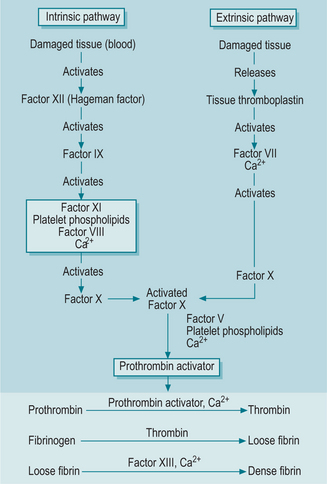

Coagulation is a complex process involving two pathways and a series of steps in each (Fig. 4.6). In summary, strands of fibrin are synthesized by a plasma protein, fibrinogen, which combines with water and solutes to form a gel in which blood cells become trapped. This is the thrombus – blood clot. As further chemicals become involved, the thrombus hardens and seals the blood vessel, and also acts as scaffolding for the repair of the damaged blood vessel. Finally, on completion of the repair, the fibrin thrombus is dissolved by the process of fibrinolysis to re-open the blood vessel fully for effective blood flow.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF THROMBOEMBOLISM

Any situation in which blood flow is slow or disrupted places the individual at risk of a thromboembolic event. Recent press has highlighted this risk in publicizing the dangers of immobility aggravated by dehydration on ‘long haul’ flights (Box 4.1). This risk has been well recognized for many years in healthcare and has led to rapid mobilization and physiotherapy in all patients post-surgery. Despite this, thromboembolic disorders continue to result in high mortality and morbidity rates, with commensurate healthcare costs.

Box 4.1 DVT and long haul flying

Pathophysiological changes associated with flying give rise to several significant predisposing factors for developing a DVT (Shepherd & Edwards 2004). Hypoxia and vasoconstriction develop over time and at high altitudes due to an increase in blood pressure and heart rate. Cabin pressure is set for 6000 feet andlong haul flights take place at much higher levels. These changes are aggravated by immobility anddehydration. After 1 h at these high altitudes, thereis a decrease in blood flow to the lower limbs and pooling of plasma proteins (Willcox 2004), thus increasing the risk of thrombosis. Additionally, pressure from the seat on the back of the leg and the cramped conditions in economy seats increasethe risk factors. Antiembolic stockings can be considered to reduce this risk but these are not suitable for some people with pre-existing disease (Scurr et al 2001). Walking around the aisles of the aircraft and preventing dehydration by drinking water (not alcohol) will help reduce the risks of DVT.

Aetiology

A thrombosis is the formation of a clot – thrombus –inside a blood vessel, thus obstructing the flow of blood through the circulatory system. The term ‘thromboembolism’ is a term applied to the formation of a thrombus complicated by the risk of embolization. An embolus is a moving clot.

Classically, the development of an inappropriate thrombosis is caused by a disruption in one or more of the following (Virchow’ striad 1856):

Venous stasis describes any condition in which venous blood flow slows or stagnates and occurs as a result of an overabundance of, or decreased removal of fluid. Common causes of venous stasis are (Gutierrez & Peterson 2002):

There are two main types of thrombus – venous and arterial. Venous thrombosis can occur in any of the veins of the body, for example a deep venous thrombosis. Common arterial thromboses are found in the coronary arteries, resulting in a myocardial infarction, or in cerebral arteries, causing a cerebrovascular accident (‘stroke’). Both of these disorders can also be caused by an embolism, but a myocardial infarction is often the result of damage to the blood vessel walls by atherosclerotic plaque to which platelets are attracted. A cerebrovascular accident (CVA) can have many causes including thrombosis due atherosclerosis (seeCh. 8).

Thromboembolic related conditions

Varicose veins

Blood flow in legs can slow and pool during inactivity of skeletal muscle. This is particularly true for those whose occupations require them to stand for long periods (Bentley 2003). When the plantar veins are compressed, as in walking, blood flow is increased into deep veins. Pressure in the veins is highest on standing but decreases on walking. In the supine position, blood pressure in the veins is negligible.

Common sites for varicosities are:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree