TOWARDS EVIDENCE-BASED HEALTH POLICY: THE IMPORTANCE OF RESEARCH

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) ‘Health for All’ initiatives at Geneva in 1977, and the Health Targets and Implementation (Health for All) Committee’s report to Australian health ministers in 1988, encouraged the importance of research in health policy. The WHO Health for All perspective clearly identifies healthy public policy as the framework within which are contained all other health initiatives. An intersectoral approach includes transport, housing, employment and education as well as health. More recently, the phrase ‘whole-of-government approach’ is applied. A former Minister for Community Services and Health in 1988 recognised that to improve health and to reorient health services towards illness prevention involved long-term structural change, which could only be achieved by ‘the establishment of expanded national statistics and public health research programs to provide data on which to base long-term policy decisions’ (Blewett 1988 p 110). Subsequent governments have emphasised evidence-based health policy. The growth of evidence-based health policy grew out of the move towards evidence-based medicine (EBM), and has largely focused on international and national burden of disease studies. Neither evidence-based health policy nor EBM has been implemented as successfully as their proponents might have hoped, although the momentum is gathering.

Research projects related to health rarely have policy as a specifically identified focus, but most research into health and healthcare has implications for policy development. Research that includes an epidemiological component and explores the patterns of health and ill health in a population is highly relevant for health policy. Much of this research is organised around priority areas in health, the National Health Priority Areas (NHPA), to improve the health status of Australians. The NHPA have been added to incrementally from their introduction in 1994 by the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, including federal, state and territory health ministers, and now (2007) comprise: cancer control; cardiovascular health; mental health; injury prevention and control; diabetes; asthma; chronic diseases; arthritis and musculoskeletal conditions; and communicable diseases. A number of priority age groups for health interventions have recently been outlined and these include mothers and babies, children, young people, and older people. Together, the first six of the NHPA accounted in 1996 for 70% of the total burden of disease and injury in Australia (Mathers et al. 1999). The NHPA initiative recognised that to reduce the burden of disease, health policy should focus on those areas that contributed significantly to death and disease (but see Baum [1995] for a critique of goals and targets in health promotion and policy). The burden of disease trends in mortality and morbidity can also be extrapolated into the future, thus allowing policy to be made in advance of the trends. As Murray and Lopez (1996 p 740) argued, ‘A major effort to foster an independent, evidence-based approach to public health policy formulation is the Global Burden of Disease Study’. This arose in 1992 from a collaboration between the World Bank and WHO. Murray and Lopez refer throughout to the need to collect and to provide evidence for policy makers about the health problems of populations: ‘Public health policy formulation desperately needs independent, objective information on the magnitude of health problems and their likely trends, based on standard units of measurement and comparable methods’ (1996 p 740).

Health is now not only about illness, but about keeping healthy. Health is perceived as stemming from an emphasis on a healthy lifestyle at any age. Regular exercise and healthy eating are seen as contributing to a reduction in the incidence of Type II diabetes, to maintaining bone density and to a lowering of high blood pressure and high cholesterol. Governments at state, territory and federal levels exhort us to health with slogans such as ‘use it or lose it’, or ‘go for your life’, and for protection from too much UV sunlight; ‘slip, slop, slap’. It is of course less expensive for governments in the long run if people can remain in their homes for as long as possible, and reduce the need for medical visits and hospital and other institutional care.

Importantly, evidence-based health policy focused on risk factors, which had not been associated with the concern for individual illness and treatment. Looking at whole populations could include such factors as socioeconomic status, thus leading to large health gains from public health interventions. Important too in evidence-based health policy is the Social health atlas of Australia (Glover et al. 1999) and its related atlases for each state and territory based mainly on Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) data. Its aims are ‘to illustrate [through maps] the socioeconomically disadvantaged population and to compare this with patterns of distribution of major causes of illness and death, use of health services and health risk factors’ (Glover et al. 1999 p 3).

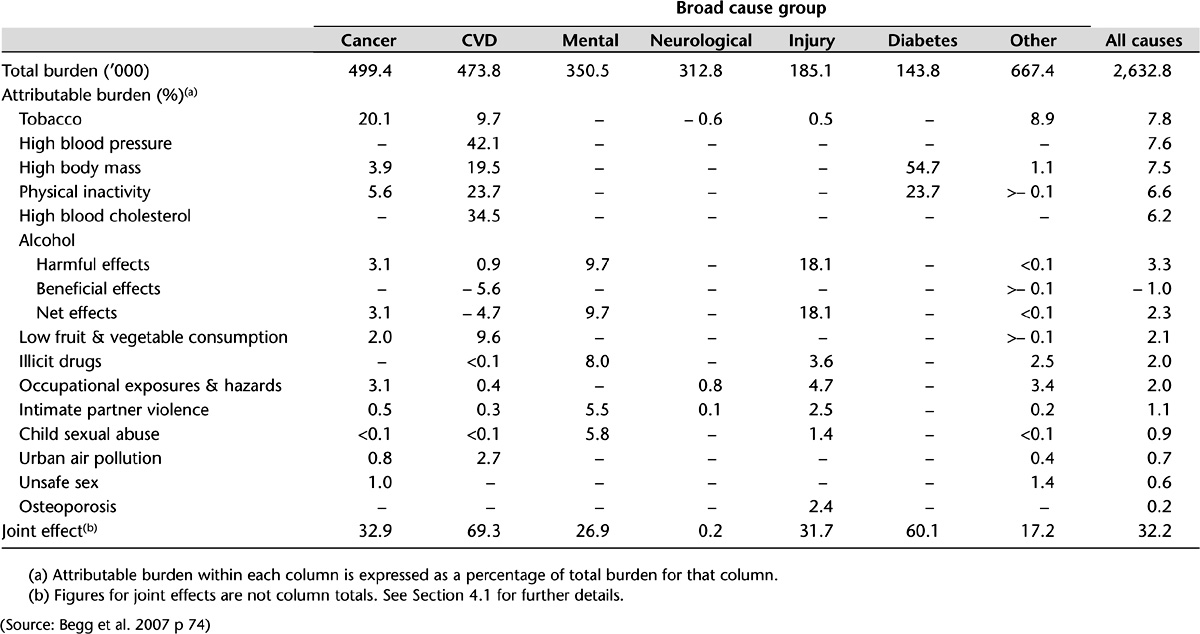

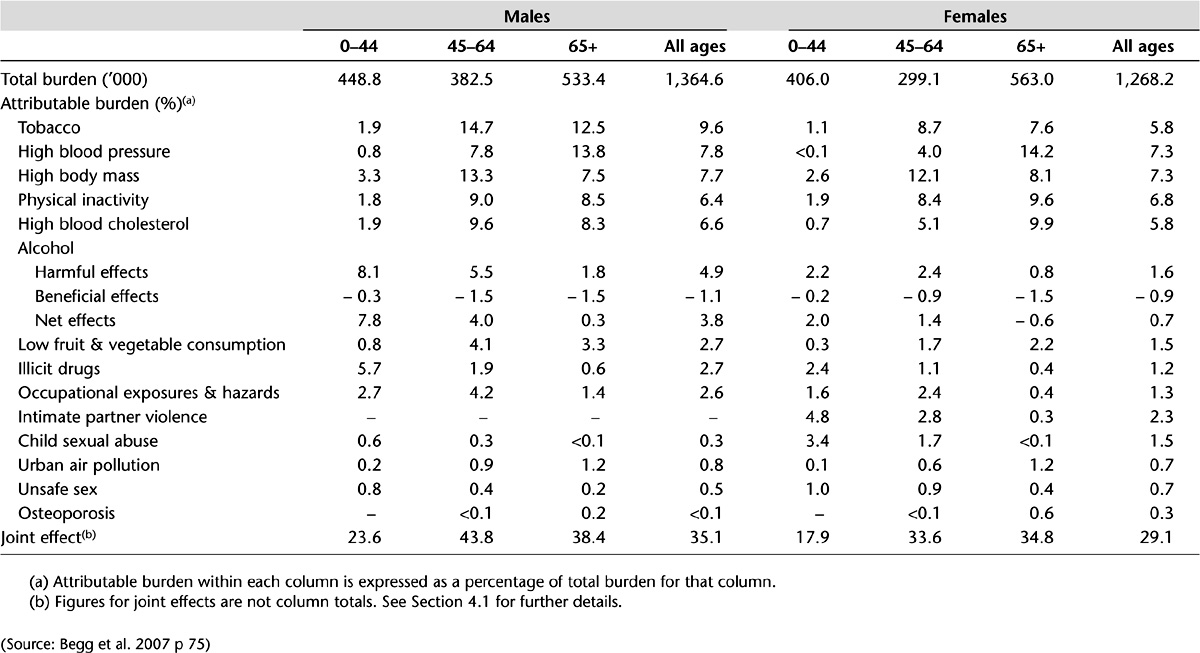

The 14 risk factors in the Australian burden of disease study (Begg et al. 2007) include physical inactivity, low fruit and vegetable consumption, high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol and unsafe sex. Tobacco smoking was the risk factor responsible for the greatest burden of disease in Australia (see Tables 4.1 and 4.2 for selected determinants of health and their associated burden of disease). And as predicted by the Victorian Burden of disease study (Department of Human Services [DHS] 2001) on the basis of trends in mortality and morbidity, and in common with international and Australian studies, mental health disorders and diabetes will increase (Begg et al. 2007). In Chapter 5, the importance and application of Health Impact Assessment (HIA) in policy analysis is assessed.

Table 4.1 Individual and joint burden (DALYs) attributable to 14 selected risk factors by broad cause group, Australia, 2003

Table 4.2 Individual and joint burden (DALYs) attributable to 14 selected risk factors by sex and age group, Australia, 2003

COMMUNICABLE DISEASE

It could be argued that the kind of research funded has implications for subsequent policy development; for example, the stress on clinical research might lead to increased costs from the impetus given to technological development and pharmaceutical usage, whereas a focus on population health might reduce costs by emphasising the prevention of ill health. In the end, however, it is not researchers but policy planners, political decision makers, who choose to act upon the accumulated knowledge that might inform policy. The actual policy outcomes of a piece of research are often beyond the control of the researchers themselves, even if that research has been sought and funded by governments. Timing is also important. Because there are statistics about, say, an increase in a communicable disease, it does not mean that there will immediately be a policy response. The trend might need to be quite strong before there will be any action, and even then it will often come as a response to media or health professional pressure until the Minister for Health, or in some cases the Prime Minister, intervenes.

The Prime Minister promptly announced the introduction in 2007, after the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) had suggested a longer timeframe, of a free vaccination program for teenage girls and young women against the human papilloma virus (HPV) that can lead to cervical cancer. The TGA is the expert authority on efficacy and cost (Ch 17). The response was a community and political one. When the medical scientist who discovered the vaccine is made Australian of the Year for that discovery, it is difficult to deny its medical significance or its political importance. Not only that, but it is also about the health of young people and ultimately would be responsible for preventing death from cervical cancer. The decision had all the aspects of values, ethics, science and politics. Part of the political opposition to the decision was that it would increase sexual promiscuity; a moral rather than an evidentiary conclusion, and one that could hardly stand up to rational argument about how many lives could be saved. Although cost was not mentioned in the public announcements, this was obviously a consideration for the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) and indeed CSL, the manufacturer, did reduce the production price. In this case, the policy was based on research evidence, but it was a political decision in the end.

Infectious disease had been for many years considered to be part of the ‘old public health’ and largely eradicated by improvements in sanitation, hygiene, clean water and the use of antibiotics to give way to the ‘new public health’, which was more concerned with the so-called diseases of lifestyle. But in the 21st century, the world is facing problems from infectious diseases, from AIDS to influenza, comparable only to the great plague, and the influenza pandemic of 1919. Australia’s response to the threat of an avian influenza pandemic has been to lead the world in developing a vaccine. At first it was believed that we could not supply everyone but only emergency workers, health professionals and perhaps those most at risk if the H5N1 bird flu virus mutated and become capable of being transmitted between humans. In early 2007, however, the TGA gave regulatory approval to a vaccine that had passed its safety and efficiency measures and which protects against H5N1. CSL said that it could produce the vaccine quickly and in large quantities (Catalano 2007 p 6).

There are also less dramatic but still serious trends in infectious disease. A concerning increase in the rate of chlamydial infection is the result of a steady trend upwards and, while receiving some small amount of publicity in the media, it needs substantial pressure from the health professions before opportunistic tests on young women are carried out at the same time as the Pap smear test. The population rate (male and female) of the diagnosis of chlamydia more than doubled between 2000 and 2004: from 91.4 per 100,000 in 2000 to 186.1 per 100,000 in 2004 (AIHW 2006a). Notifications had been rising by 20% per year for the previous 5 years. Chlamydia is largely unnoticed in young women until the infection, in some women, causes such damage to the reproductive system that infertility is found, too late. Much money in the IVF program, not to mention distress, could be saved should a simple test be carried out in GPs’ surgeries. Currently, there are limited pilot studies being conducted to see the best way for testing young men and women for chlamydia infection before a national screening program can even begin. It is cost and competing priorities that can decide health priorities, although communicable diseases have been added to the national health priority areas (see above). The $12.5million allocated for the pilot studies was part of the first National Sexually Transmissible Infections Strategy for 2005–2008. Values are also important; sexual health is not something people like to talk about.

DATA FOR HEALTH

In some respects health research and funding mirror the federal system in Australia, which in turn is reflected in the organisation of the healthcare system in general; it is fragmented between the states, territories and the Commonwealth and there are gaps and duplication. There have, however, been huge inroads into the comprehensive collection of health and welfare data, largely due to the work of the AIHW since 1987. Indeed, the AIHW’s mission statement is the ‘Better health and wellbeing for Australians through better health and welfare statistics and information’. Working in partnership with the states and territories and with many research organisations, universities and health departments and the ABS, comprehensive data on health, housing and the community are now collected and disseminated (see also Ch 11). Evidence for the importance of research data can be gauged by the increased number of annual publications from the AIHW, from its conferences, and from its online usage and initiatives, such as its METeOR metadata management tool. The range of health areas researched can be gauged from its publications from Developing a nationally consistent data set for needle and syringe programs (AIHW 2007a) to the regularly released Health expenditure bulletin (AIHW 2006b), and the National public health expenditure report 2004–05 (AIHW 2007b). Similarly, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) advises the government on health and health research but, as Swerissen (1998 p 205) argues, although rational from a scientific point of view, in the ‘relatively packed gallery’ of interest groups, medical researchers and scientists are only a small part and, like the other groups, not always disinterested.

The medical profession, largely through the international Cochrane Collaboration, which reviews medical research articles and subjects them to meta analyses, relies for excellence (the gold standard) on randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and is enlarging the amount of its work which is evidence based (evidence-based medicine or EBM). Chapter 19 provides a useful account of EBM guidelines for prostate cancer. The Australian government funds the Cochrane Centre through the NHMRC. Still, only approximately 20% of the work of medical professionals is evidence based. Other health professions, such as physiotherapy and occupational therapy, have also supported an evidence base to their interventions.

ACCOUNTABILITY AND COST EFFECTIVENESS

Just as health policies are now more likely to be based on research, there is an increased recognition of the importance of evaluation of health programs (Mooney & Scotton 1999), which is linked both to notions of accountability and to scarcity of resources, which in turn are linked. There is a danger, however, that research for health policy development could become even more limited if, in a situation of scarcity and continued pressure on resources, it becomes confined to evaluations of existing health programs. Health research units within state and territory health departments are themselves subject to limited funding but have carried out some important research, as in the burden of disease, population health studies, and on inequalities in health. For example, in Victoria the first burden of disease study was carried out in 1996 and revised in 2001 and provides important information on health status, not only for the state government but also for local government level planning (DHS 2001). The states and territories contribute enormously to the collection of health data provided to the AIHW and evaluate many specific state, territory and local government programs in health and related areas. See, for example, the Environments for Health evaluation project in Victoria in Butterworth’s chapter (Ch 8); see also Chapter 21 for a discussion of environmental health programs and risk factors in, for example, the supply of our food.

Australia has had a relatively rational approach to healthcare decision making, which now involves a cost component as well as a safety and effectiveness component. Prescribed pharmaceuticals are approved for the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) by the PBAC after being examined by the TGA. Health services provided by GPs and public hospitals since 1984 come under Medicare and the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS), and medical services are, from 1997, subject to the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC). Incrementalism is evident in the regular changes to the groups of services already listed on the MBS to reflect the availability of new technologies or changes in medical practice or the addition of a new item. However, before a new procedure or technology can be listed on the MBS, its safety, effectiveness and cost effectiveness has to be assessed by the MSAC. MSAC assesses the evidence base of medical technologies. The aim is to ensure that the community has access to the best possible quality healthcare services at an affordable cost (Department of Health and Aged Care [DH&AC] 1999). Again, in common with the NHPA, if the Australian government is going to spend money, it has to be in an area that is going to be effective based on evidence or in the public service vernacular ‘more bang for your buck’. It is worth quoting the then Department of Health and Aged Care (DH&AC) in full about the context for this emphasis on cost and outcome effectiveness:

Meeting this aim has become increasingly important because of the pressures on healthcare expenditure, which has been steadily increasing … In 1996–97, expenditure on medical services via the MBS was around $A6.2 billion. Factors contributing to increases in healthcare include population growth, demographic changes, developments in new medical technologies, increasing fees and costs of delivering healthcare services, growth in the medical workforce and greater community expectations.Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree