CHAPTER 4. Assessing importance, confidence and readiness

• Introduction

• Scaling questions; a strategy for a more structured approach

• A more conversational approach

• What to talk about next: importance or confidence?

• Four strategies for assessing readiness to change

• Conclusions: readiness, importance, and confidence

• A case example of agenda-setting and assessment of importance and confidence

Assess importance

How do you feel at the moment about [change]? How important is it to you personally to [change]? If 1 was ‘not at all important’ and 10 was ‘very important’, what number would you give yourself?

Assess confidence

If you decided right now to [change], how confident do you feel about succeeding with this? If 1 was ‘not at all confident’ and 10 was ‘very confident’, what number would you give yourself?

Assess readiness

People differ quite a lot in how ready they are to change their… What about you?

Introduction

I’d love to give up smoking. I know it’s bad for my health, the kids hate me smoking and it is becoming even more of a problem now that everywhere has become non-smoking. I just don’t seem to be able to though. I’ve tried several times and the longest I last is about 3 weeks, so I’ve just about given up trying.

I could cut down my drinking any time if I really wanted to. When I went on that diet 2 years ago, I didn’t drink at all for 6 weeks. But I don’t see any need to cut down at the moment. I’m fit, I never get bad hangovers, and it doesn’t interfere with my work or my family. If I saw the need, I would just do it.

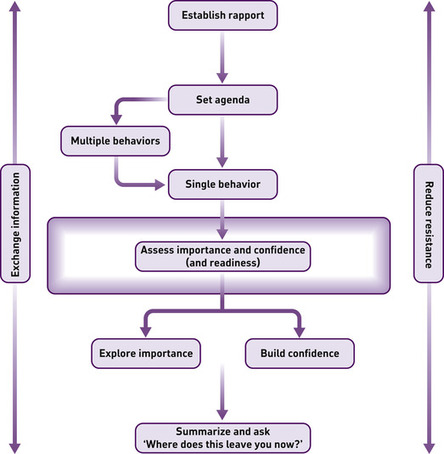

It seems that some people cannot change and others do not want to. This chapter explores how to assess someone’s readiness to change using these two dimensions, and then how to respond, focusing on the element that is holding the patient back from change.

We have suggested that a person’s readiness to change (a more global concept) is influenced by his or her perceptions of importance and confidence, i.e. he or she can explain his or her stated position on a readiness to change continuum (see Chapter 2, Figure 2.3, p. 30). Someone might be convinced of the personal value of change (importance), but not feel confident about mastering the skills necessary to achieve it (confidence). This applies to many smokers, such as the first patient above. Heavy drinkers, on the other hand, like the second patient above, can be quite different. They often have mixed feelings about the value of change (importance), but say that they could achieve this fairly easily (confidence) if they really wanted to. When it comes to changes in eating patterns, people often have relatively low levels on both dimensions.

Having agreed to talk about a particular behavior, there are a number of directions one could take. We have found that the assessment of importance and confidence is a useful first step, hence our decision to use this as the fulcrum for decision-making in this approach. Put simply, it helps you understand exactly how someone feels about change. It also helps you focus your limited time and resources on the most salient issue for each patient. We are not suggesting that this task needs to be carried out in every consultation. One might, for example, already know how a patient feels about change, or at least have a strong intuition about this. You might decide to carry out another task, for example, exchanging information (Chapter 6), or use a strategy for exploring importance (Chapter 5). If the consultation is like a journey, assessing importance and confidence is one route that can profitably be taken.

Practitioners have different styles. Some people work in a less structured, more organic way and their style is more conversational. Others prefer to have structured questions to ask and something of a format to follow. Below, we discuss how to conduct this assessment in each style. In both cases, the assessment can take as little as 2–3 minutes.

As our patients’ health is our priority, it is easy to assume that it is theirs too. This can lead us to imagine that they share our conviction that it is important to change, and that what is holding them back is that they don’t know how best to do so. In turn, this can lead to an intervention based on practical advice with a touch of cheerleading thrown in to boost motivation. Not all patients will be helped by such an approach.

So, we both know how important it is for you to lose weight. Let’s find a diet that you think would work for you and book you into our slimming club to give you some moral support. I can see you don’t look very enthusiastic, but we’ve had lots of success in helping people lose weight and you’re really going to notice the difference in your health.

Scaling questions: a strategy for a more structured approach

How do you feel at the moment about [change]? How important is it to you personally to [change]? If 1 was ‘not important’ and 10 was ‘very important’, what number would you give yourself?

If you decided right now to [change], how confident do you feel about succeeding with this? If 1 was ‘not confident’ and 10 was ‘very confident’, what number would you give yourself?

Many health practitioners have experience of scaling questions like these, and patients may have experience in answering them in other contexts. They are frequently used in pain management and mood management, and were first used in consultations about behavior change by de Schazer et al (1986). We have adapted them for our purpose here.

There are different ways of phrasing them, of course. It is helpful to clarify which end of the scale is which. The words importance and confidence seem to be the least ambiguous to express the ideas we are after. If, instead of asking how important something is, you ask How motivated are you?, the answer will sometimes be an amalgam of importance and confidence and be less useful in understanding the patient’s position. One of us heard a patient, in response to being asked How motivated are you? say About a 5… I really want to but I don’t know how possible it is! Asking the questions as described above might have produced an 8 for importance and a 3 for confidence, which would have been much more helpful in deciding where to go next than the 5 which seemed to be an average of the two.

Sometimes, a patient will simply respond to the importance question by saying, Very important. In this case, you can move directly into the process of exploring importance described in Chapter 5. A useful and obvious response is simply to ask, Why? This will invite the patient to speak in a positive way about the value of change. These and other ways of responding are described in detail below.

A concept linked to importance is that of wanting to change or even keenness to change. The assessment question could be framed thus:

How do you feel at the moment about [change]? How much do you want to [change]? If 1 was ‘not at all’ and 10 was ‘very much’, what number would you give yourself?

Scrutiny of the latter two questions reveals that they approach the more general concept of readiness, or motivation, to change. We have not suggested using this latter term in the assessment because, as noted above, some of our earlier work (see Rollnick et al 1997) led to theoretical confusion about the meaning of the term motivation. In this particular assessment, we are interested in penetrating the patients’ feelings and views about the costs and benefits of change; how they personally value change and whether it will, on balance, lead to an improvement in their lives, as distinct from the issue of their confidence to master the demands of this change.

In keeping with the meaning of the term self-efficacy, we are interested, when asking about confidence, not in a general sense of self-belief or self-esteem, but in confidence about mastering the various situations in which behavior change will be challenged.

Introducing the assessment

The patient should fully understand why you would like to use this strategy, and rapport should be good. It can be introduced thus:

I am not really sure exactly how you feel about [behavior or change]. Can you help me by answering two simple questions, and then can see where to go from there?

At this point, pause and deal with whatever response the patient makes. Sometimes, they do not allow you to get going, and proceed to tell you how they feel! This is exactly what you want. Leave the assessment aside, and return to it if you are still confused.

If the patient seems disengaged, do not do the assessment. Attempt to raise the level of engagement first. Express curiosity. If your rapport is good enough, you can challenge the patient in a friendly way, for example:

Have you ever sat down with someone and told them exactly how you feel about [behavior or change]? I’d be interested to hear how it sounds from your perspective.

Or check it out with them:

In a discussion like this, it can be a mistake to jump too quickly to talk about doing this or doing that. I certainly don’t want you to feel pressurized in any way. We could talk about something else.

A visual aid can help

Even when doing a more formal assessment, the patient must be actively involved. You provide the structure, and the patient does the rest. If it looks or feels like a question and answer assessment session, you are falling short of the ideal.

• The assessment can be done verbally, using the questions above; the readiness rule can be downloaded from the website (www.elsevierhealthbehaviorchange.com) or photocopied from Appendix 3, or you can just draw lines on a scrap of paper by way of a visual aid!

• The spirit of this exercise is most important. You need to feel genuinely curious. It is not an investigation, but an inquiry.

• The goal of the assessment is to work out which of the two domains, importance or confidence, should be your focus.

• The words one uses can be critical; for example, a smoker talking about quitting might respond differently to questions about her confidence to ‘give it a try’, ‘stop for a week’, or ‘never touch a cigarette again’.

How we developed this strategy

This more standardized assessment procedure emerged from experimentation with smokers (Rollnick et al 1997, Butler et al 1999). Our starting point was a need to develop a method that we could teach to family practitioners for use in consultations lasting 7–10 minutes. Our goal was to find a way of conducting a quick psychological assessment of smoking, i.e. 2–3 minutes, which could lay the foundation for a conversation about change. In our pilot work with a group of volunteer smokers, we began with a readiness to change continuum, hoping to use this as a guide to the choice of strategy that the practitioner might use. Initially, we became confused by the fact that people placing themselves in similar positions on a readiness continuum had such different needs. The choice of strategy was not immediately apparent from the person’s stated readiness to change. We started asking them why they had put a mark on a given point on the continuum, and then it struck us that the conversations tended to embrace two topics, importance and confidence, as described in Chapter 2. We then decided to assess these dimensions directly, and developed a single-page intervention method, based on this assessment, which was used for training practitioners (Rollnick et al 1997). We also found that they subsequently used this assessment in everyday practice, and not just with smokers but in other behavior change discussions.

When used in our own consultations with other kinds of behavior change problems, very few patients have difficulty with the numerical scaling technique on which the assessment is based. Of course, this depends crucially on the specificity and relevance of the change under discussion. The more specific the change, the easier it is to understand the assessment. In essence, this assessment of importance and confidence is a structured and directive way of en-abling patients to say how they feel about a particular change within a couple of minutes. Its orientation is patient-centered; it provides a platform for responding to the domain defined by the patient as being in greatest need of attention. The decision where to go next within each domain is dealt with in Chapter 5. Our focus here is merely on assessment.

A more conversational approach

The assessment can also be done informally. The following example illustrates the conversational process of unraveling which dimension is of greatest concern to the patient; in this case, in a conversation about exercise. An informal assessment of importance and confidence is shown below:

Practitioner: So, we have identified that you get very little exercise since your promotion to an office-based job, and consequently you have put on some weight. You also find the new job stressful and could do with a way of letting off steam. How do you feel about organizing some sort of physical activity for yourself now that you are not in a physically demanding job?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access