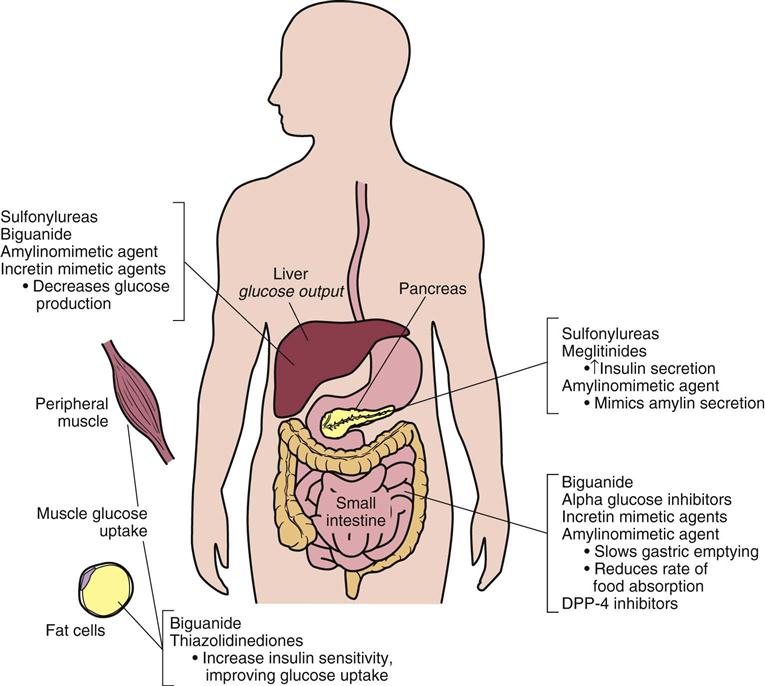

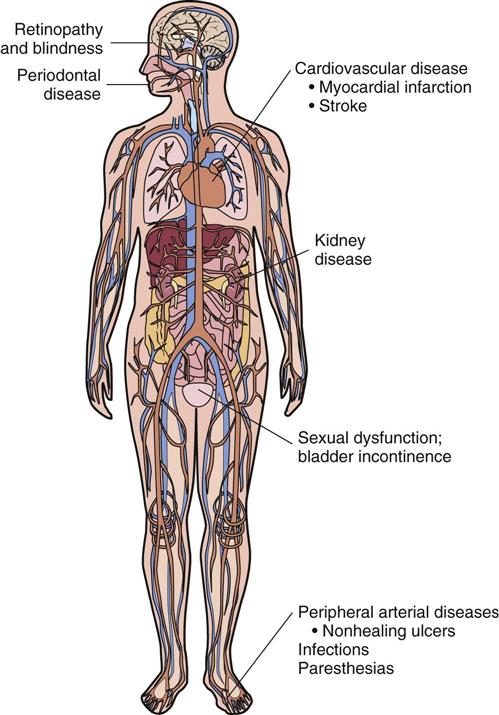

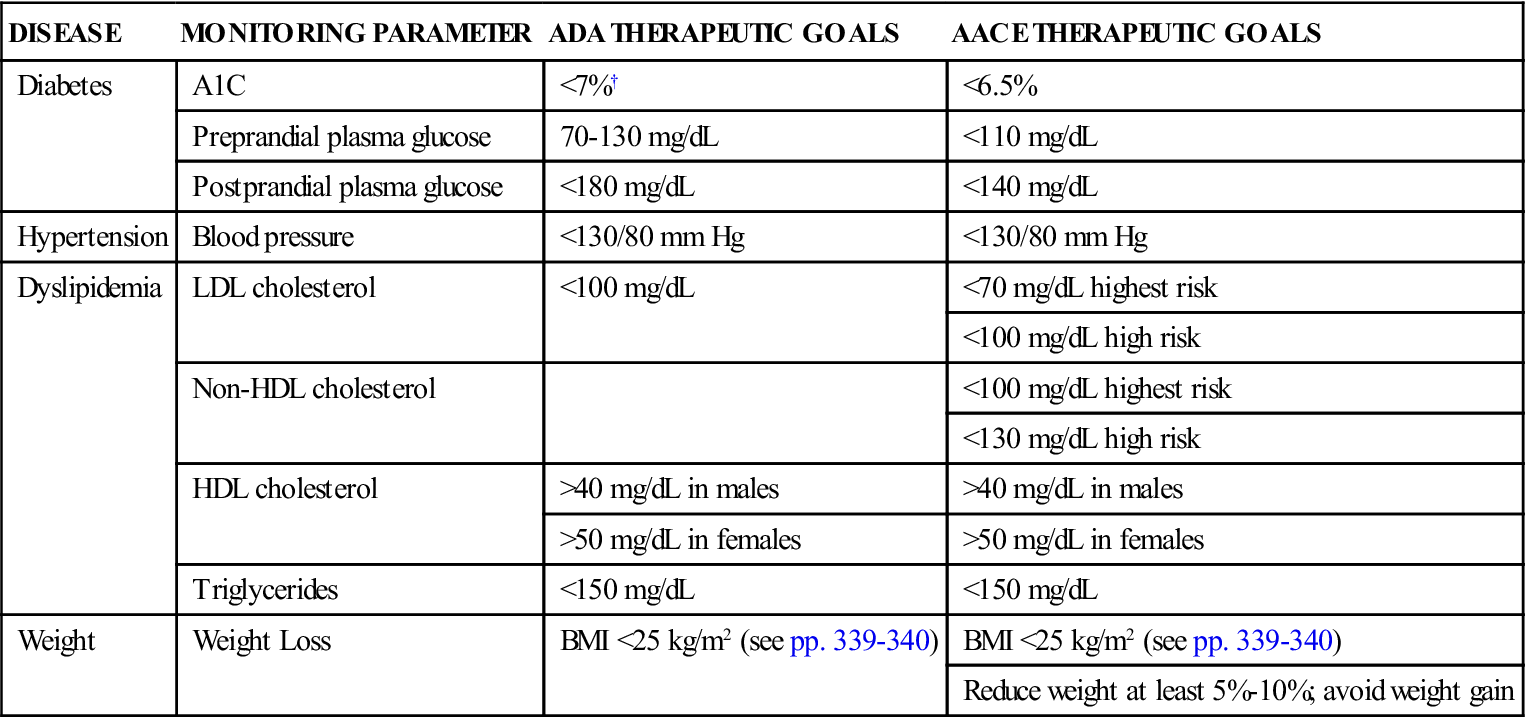

3 Identify the objectives of dietary control of diabetes mellitus. 4 Discuss the action and use of insulin to control diabetes mellitus. 5 Discuss the action and use of oral hypoglycemic agents to control diabetes mellitus. 7 Differentiate among the signs, symptoms, and management of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. diabetes mellitus ( hyperglycemia ( type 1 diabetes mellitus (p. 561) type 2 diabetes mellitus (p. 561) gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) ( impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) ( impaired fasting glucose (IFG) (p. 562) prediabetes ( microvascular complications ( macrovascular complications ( neuropathies ( paresthesia ( hypoglycemia ( intensive therapy (p. 564) Diabetes mellitus is a group of diseases characterized by hyperglycemia (fasting plasma glucose level >100 mg/dL) and abnormalities in fat, carbohydrate, and protein metabolism that lead to microvascular, macrovascular, and neuropathic complications. Several pathologic processes are associated with the development of diabetes, and patients often have impairment of insulin secretion as well as defects in insulin action, resulting in hyperglycemia. It is now recognized that different pathologic mechanisms are involved that affect the development of the different types of diabetes. Diabetes mellitus is occurring with increasing frequency in the United States as the population increases in weight and age. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2011) estimates that the prevalence of diabetes in the general population is approximately 8.3% (25.8 million people, 7 million of whom are undiagnosed). Direct expenditures of medical care totaled $116 billion in 2007. An additional $58 billion was attributed to lost productivity at work, disability, and premature death. Diabetes is listed as the sixth leading cause of death in the United States. Most diabetes-related deaths are the result of cardiovascular disease because the risk of heart disease and stroke is two to four times greater in patients with diabetes compared with those without the disease. Undiagnosed diabetic adults, with few or no symptoms, present a major challenge to the health profession. Because early symptoms of diabetes are minimal, many of these people do not seek medical advice. Indications of the disease are discovered only at the time of routine physical examination. Those with a predisposition to developing diabetes include people who have relatives with diabetes (they have a 2.5 times greater incidence of developing the disease), obese people (85% of all diabetic patients are overweight), and older people (four out of five diabetic patients are older than 45 years). The incidence of diabetes is higher in African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, Native Alaskans, and women. There also appears to be a significant increase in diabetes among those younger than 20 years. The CDC has a major study underway to quantify this perception. The National Diabetes Data Group of the National Institutes of Health and the World Health Organization Expert Committee on Diabetes (NDDG/WHO) classify diabetes by the underlying pathology causing hyperglycemia (Box 36-1). Type 1 diabetes mellitus, formerly known as insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), is present in 5% to 10% of the diabetic population. It is caused by an autoimmune destruction of the beta cells in the pancreas. It occurs more frequently in juveniles, but patients can become symptomatic for the first time at any age. The onset of this form of diabetes usually has a rapid progression of symptoms (a few days to a few weeks) characterized by polydipsia (increased thirst), polyphagia (increased appetite), polyuria (increased urination), increased frequency of infections, loss of weight and strength, irritability, and often ketoacidosis. Because there is no insulin secretion from the pancreas, patients require administration of exogenous insulin. Insulin dosage adjustment is easily affected by inconsistent patterns of physical activity and dietary irregularities. It is common for patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus to go into remission in the early stages of the disease, requiring little or no exogenous insulin. This condition may last for a few months and is referred to as the “honeymoon” period. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, formerly known as non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM), is present in 90% to 95% of the diabetic population. In contrast to type 1 diabetes mellitus, type 2 diabetes is characterized by a decrease in beta cell activity (insulin deficiency), insulin resistance (reduced uptake of insulin by peripheral muscle cells), or an increase in glucose production by the liver. Over time, the beta cells of the pancreas fail and exogenous insulin may be required. Most people with type 2 diabetes mellitus also have metabolic syndrome, also known as insulin resistance syndrome and syndrome X (see Chapter 21). Type 2 diabetes onset is usually more insidious than that of type 1 diabetes. The pancreas still maintains some capability to produce and secrete insulin. Consequently, symptoms (polyphagia, polydipsia, polyuria) are minimal or absent for a prolonged period. The patient may seek medical attention several years later only after symptoms of the disease are apparent (see later, “Complications of Diabetes Mellitus”). Fasting hyperglycemia can be controlled by diet in some patients, but most patients require the use of supplemental insulin or oral antidiabetic agents, such as metformin or glyburide. Although the onset is usually after the fourth decade of life, type 2 diabetes can occur in younger patients who do not require insulin for control. See Table 36-1 for a comparison of the characteristics of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Table 36-1 Features of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus* *Clinical presentation is highly variable. †Age of onset is most commonly younger than 20 years, but onset may occur at any age. As the rates of obesity increase, type 2 diabetes is becoming much more prevalent in children, adolescents, and young adults in all ethnic groups. A third subclass of diabetes mellitus (see Box 36-1) includes additional types of diabetes that have causes other than those that cause type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. They are part of other diseases having features not generally associated with the diabetic state. Diseases that may have a diabetic component include pheochromocytoma, acromegaly, and Cushing’s syndrome. Other disorders included in this category are malnutrition, infection, drugs and chemicals that induce hyperglycemia, defects in insulin receptors, and certain genetic syndromes. The fourth category of classification, known as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), is reserved for women who show abnormal glucose tolerance during pregnancy. Gestational diabetes is diagnosed in about 7% of all pregnancies in the United States, resulting in about 200,000 cases per year. (The range is 1% to 14%, depending on the population studied and the diagnostic criteria used). It does not include diabetic women who become pregnant. Most gestational diabetic women have a normal glucose tolerance postpartum. Gestational diabetic patients must be reclassified 6 weeks after delivery into one of the following categories: diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, or normoglycemia. Gestational diabetic patients have been put into a separate category because of the special clinical features of diabetes that develop during pregnancy and the complications associated with fetal involvement. These women are also at a greater risk of developing diabetes 5 to 10 years after pregnancy. There is a group of patients found to have an impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) or impaired fasting glucose (IFG). These patients are often normally euglycemic, but develop hyperglycemia when challenged with an oral glucose tolerance test. In many of these patients, the glucose tolerance returns to normal or persists in the intermediate range for years. This intermediate stage between normal glucose homeostasis and diabetes is now known as prediabetes. It is now thought that patients with IGT or IFG are at a higher risk for developing type 1 or type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in the future. The CDC has estimated that 79 million American adults over the age of 20 had prediabetes in 2010. Categories of fasting plasma glucose (FPG) levels are the following: • FPG less than 100 mg/dL = normal fasting glucose • FPG at 100 mg/dL or greater but less than 126 mg/dL = IFG • 2-hour plasma glucose level at 140 or greater but less than 199 mg/dL = IGT See Table 36-2 for criteria for the diagnosis of types 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus. Table 36-2 Criteria for Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus* *In the absence of unequivocal hyperglycemia, these criteria should be confirmed by repeat testing on a different day. The OGTT is not recommended for routine clinical use but may be required in the evaluation of patients with IFG or when diabetes is still suspected despite a normal FPG, as with the postpartum evaluation of women with gestational diabetes mellitus. †Casual is defined as any time of day without regard to time since last meal. The classic symptoms of diabetes include polyuria, polydipsia, and unexplained weight loss. ‡Fasting is defined as no caloric intake for at least 8 hours. Adapted from American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care in diabetes—2012, Diabetes Care 35(Suppl 1):S13, 2012. Long-standing hyperglycemia and abnormalities in fat, carbohydrate, and protein metabolism lead to microvascular, macrovascular, and neuropathic complications. Microvascular complications are those that arise from destruction of capillaries in the eyes, kidneys, and peripheral tissues. Diabetes has become the leading cause of end-stage renal disease and adult blindness. Macrovascular complications are those associated with atherosclerosis of middle to large arteries, such as those in the heart and brain. Macrovascular complications, stroke, myocardial infarction, and peripheral vascular disease account for 75% to 80% of mortality in patients with diabetes. Complications of diabetes mellitus that often arise include the following (Figure 36-1): • Cardiovascular disease (atherosclerosis) leading to myocardial infarction and stroke • Retinopathy leading to blindness • Renal disease leading to end-stage renal disease and the need for dialysis • Neuropathies with sexual dysfunction, bladder incontinence, paresthesias, and gastroparesis Symptoms associated with complications of diabetes may be the first indication of the presence of diabetes. Patients may complain of weight gain or loss. Blurred vision may indicate hyperglycemia or diabetic retinopathy. Neuropathies may first be observed as numbness or tingling of the extremities (paresthesia), loss of sensation, orthostatic hypotension, impotence or vaginal yeast (candidiasis) infections, and difficulty in controlling urination (neurogenic bladder). Nonhealing ulcers of the lower extremities may indicate chronic vascular disease. Diabetic complications can be delayed or prevented with continuous normoglycemia, accomplished by monitoring blood glucose levels; drug therapy; and treatment of comorbid conditions as they arise. Although the classification system of the NDDG/WHO was developed to facilitate clinical and epidemiologic investigation, the categorization of patients can also be helpful in determining general principles for therapy. Because a cure for diabetes mellitus is unknown at present, the minimal purpose of treatment is to prevent ketoacidosis and symptoms resulting from hyperglycemia. The long-term objective of control of the disease must involve mechanisms to stop the progression of the complications of the disease. Major determinants of success are a balanced diet, insulin or oral antidiabetic therapy, routine exercise, and good hygiene. Patients with diabetes can lead full and satisfying lives. However, unrestricted diets and activities are not possible. Dietary treatment of diabetes using medical nutrition therapy (MNT) and exercise constitutes the basis for management of most patients, especially those with the type 2 form of the disease. With adequate weight reduction, exercise, and dietary control, patients may not require the use of exogenous insulin or oral antidiabetic drug therapy. People with type 1 diabetes will always require exogenous insulin as well as dietary control because the pancreas has lost the capacity to produce and secrete insulin. The aims of dietary control are the prevention of excessive postprandial hyperglycemia, the prevention of hypoglycemia (blood glucose level less than 60 mg/dL) in those patients being treated with oral antidiabetic agents or insulin, the achievement and maintenance of an ideal body weight, and a reduction of lipids and cholesterol. A return to normal weight is often accompanied by a reduction in hyperglycemia. The diet should also be adjusted to reduce elevated cholesterol and triglyceride levels in an attempt to retard the progression of atherosclerosis. To help maintain adherence to dietary restrictions, the diet should be planned using the American Diabetes Association (ADA) MNT recommendations in relation to the patient’s food preferences, economic status, occupation, and physical activity. Emphasis should be placed on what food the patient may have and what exchanges are acceptable. Food should be measured for balanced portions, and the patient should be cautioned not to omit meals or between-meal and bedtime snacks. Patient education and reinforcement are extremely important to successful therapy. The intelligence and motivation of the diabetic patient and his or her awareness of the potential complications contribute significantly to the ultimate outcome of the disease and the quality of life that the patient may lead. All diabetic patients must receive adequate instruction on personal hygiene, especially regarding care of the feet, skin, and teeth. Infection is a common precipitating cause of ketosis and acidosis and must be treated promptly. Patients with diabetes must also be aggressively treated for comorbid diseases (smoking cessation, treatment of dyslipidemia, blood pressure control, antiplatelet therapy, influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations) to help prevent microvascular and macrovascular complications. The ADA and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (ACCE) have developed programs of intensive diabetes self-management that applies to type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. These programs include the concepts of care, the responsibilities of the patient and the health care provider, and the appropriate intervals for laboratory testing and follow-up. Patient education, understanding, and direct participation by the patient in his or her treatment are key components of long-term success in disease management. Intensive therapy describes a comprehensive program of diabetes care that includes self-monitoring of blood glucose four or more times daily, MNT, exercise, and, for those patients with type 1 diabetes, three or more insulin injections daily or use of an insulin pump for continuous insulin infusion. See Table 36-3 for the treatment goals recommended by the ADA and the ACCE. Table 36-3 Treatment Goals for Diabetes and Comorbid Diseases* BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein. *Recommended by the American Diabetes Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. †The goal hemoglobin A1C level for patients in general is less than 7%, but the ideal goal for individual patients is as close to normal (<6%) as possible without significant hypoglycemia. Modified from AACE Task Force for Developing a Diabetes Comprehensive Care Plan, Diabetes Care Plan Guidelines 17(suppl 2), 2011. The primary treatment goal of type 1 and type 2 diabetes is normalization of blood glucose levels. Insulin is required to control type 1 diabetes and other types of diabetes in patients whose blood glucose cannot be controlled by a MNT diet, exercise, weight reduction, or oral antidiabetic agents. Patients normally controlled with oral antidiabetic agents require insulin during situations of increased physiologic and psychological stress, such as pregnancy, surgery, and infections. The dosage of insulin is usually adjusted according to the blood glucose levels. The patient should test the blood glucose level before each meal and at bedtime while the insulin and food intake are being regulated. The ADA now recommends that patients with prediabetes be treated to prevent or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes. Patients should be referred to an effective ongoing support program targeting weight loss of 7% of body weight and increasing physical activity to at least 150 minutes per week of moderate activity such as walking. Metformin therapy should be considered for treatment of prediabetes, especially in those patients whose body mass index (BMI) is greater than 35 kg/m2, are older than 60 years, and women with prior GDM. Patients should be monitored at least annually for the development of diabetes mellitus. Oral antidiabetic agents are used in the therapy of type 2 diabetes. They are recommended only for those patients whose diabetes cannot be controlled by MNT diet and exercise alone and who are not prone to develop ketosis, acidosis, or infections. Patients most likely to benefit from treatment are those who have developed diabetes after age 40 and who require less than 40 units of insulin daily. A combination of oral antidiabetic agents working by different mechanisms is often required to control hyperglycemia successfully (Figure 36-2): Initial oral antidiabetic therapy for type 2 diabetes is highly dependent on the patient’s success with lifestyle modification and diet control. A consensus statement endorsed by the ADA recommends metformin in combination with MNT and exercise as initial treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. If the goal A1C level below 7% has not been achieved with this monotherapy within 3 to 6 months, add basal insulin (most effective) and/or a sulfonylurea (least expensive), a TZD, or an incretin-based DPP-4 inhibitor or GLP-1 agonist. If the A1C level is still higher than 7%, insulin doses should be intensified, and another member of a drug class not already being used in the initial therapy should be added. An alpha-glucosidase inhibitor may be added if postprandial hyperglycemia is a problem. See Table 36-4 for a comparison of oral antidiabetic agents and their effects on lowering blood glucose levels and A1C concentrations. Table 36-4 Summary of Physiologic Effects of Antidiabetic Agents Data from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists: Medical guidelines for the management of diabetes mellitus. The ACCE system of intensive diabetes self-management, 2002 update, Endocr Pract 8(Suppl 1):52, 2002; Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Agriculture: Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2005. Available at www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines. A major challenge in nursing is to teach the recently diagnosed diabetic patient all the necessary information to manage self-care and the disease process and to prevent complications. The patient must be taught the entire therapeutic regimen—diet, activity level, blood or urine testing, medication, self-injection techniques, prevention of complications, illness management, and effective management of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. Patient education may begin in the hospital and continue for several weeks in the outpatient setting. The dietician, nurse, and diabetic nurse educators are all actively involved in educating the patient and family. A referral to the ADA serves as an excellent resource in the community for the patient and family. Many diabetic patients have difficulty understanding the critical balance that must be maintained among the dietary prescription, prescribed medication, and maintenance of general health. All are important to the control and effective management of the disease process. The order of performing the assessment depends on the setting and the severity of the patient’s symptoms. Description of Current Symptoms Patient’s Understanding of Diabetes Mellitus The FPG is the preferred test used to screen for diabetes in children and nonpregnant adults. Psychosocial Assessment Nutrition Activity and Exercise Medications. What medications have been prescribed, and what is the degree of adherence with the regimen? What over-the-counter medications (including herbal medicines) does the patient take, and how often? Does the patient consume alcohol? If so, how much and how often? Ask specifically about the type and amount of insulin being taken and the times of administration. Monitoring. Ask the patient to bring a record of self-monitoring of insulin or antidiabetic agents taken, as well as any blood glucose testing or A1C testing that was done. Has the patient done any testing for ketones? If so, what were the results? Other tests to be performed periodically include the fasting lipid profile, which includes measurement of levels of cholesterol (high-density lipoprotein [HDL], low-density lipoprotein [LDL] cholesterol, triglycerides]; serum creatinine; and microalbuminuria. Physical Assessment. Generally, data are collected about all body systems to serve as a baseline for subsequent evaluations throughout the course of treatment. Periodic focused assessments are completed to detect signs and symptoms of complications commonly associated with diabetes mellitus. Knowledge. The ADA has developed areas of diabetic education. Not all aspects of the care outlined in these recommendations are presented in the sample teaching plan for diabetics (Chapter 5, p. 51, Box 5-2). The recommendations must be adapted to the individual’s needs. It may not be possible to teach the entire program during the hospitalization period. Teach the individual specifics regarding the type of diabetes that has been diagnosed. Psychological Adjustment Smoking. Health care providers should emphasize the need for smoking cessation as a priority of care for all patients with diabetes. Nutrition • The ADA no longer endorses any single meal plan or specified percentages of macronutrients as it has in the past. The Institute of Medicine and the ADA recommend, in general, that the diet be composed of 45% to 65% carbohydrates, 15% to 20% protein (0.8 to 1 g protein/kg of body weight), and no more than 30% fat. Monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats should be the primary fat sources; saturated fats should be limited to no more than 10% of the diet and cholesterol intake to 300 mg or less daily. Trans fatty acids should be avoided when possible. Including high-fiber foods (e.g., legumes, oats, barley) assists in lowering both blood glucose and blood cholesterol levels. Reduced sodium, alcohol, and caffeine consumption is also advisable (see also Chapter 47). The ADA has several cookbooks and pamphlets on nutrition available for the diabetic person. Activity and Exercise Medication • A variety of combinations of insulin or insulin and oral antidiabetic agents may be used to provide control of the blood glucose level. The goal of therapy is to consistently maintain the blood glucose level within normal range. Administration schedules have evolved over the years to accomplish this goal. The schedules commonly used are as follows: 5 Continuous infusion of rapid- or short-acting insulin using a small, portable insulin infusion pump • Medication preparation, dosage, frequency, storage, and refilling should be discussed and taught in detail. See Chapter 11, Figure 11-3, p. 159 for administration of subcutaneous injections and Chapter 10, Figure 10-26, p. 154 for mixing of insulins. Also, discuss proper disposal of used syringes and needles in the home setting. • When a patient is experiencing an acute illness, injury, or surgery, hyperglycemia may result. When ill, the patient should continue with the regular diet plan and increase noncaloric fluids such as broth, water, and other decaffeinated drinks. The patient should continue to take the oral agents and/or insulin as prescribed, and monitor the blood glucose level at least every 4 hours. If the glucose level is higher than 240 mg/dL, urine should be tested for ketones (see Urine Testing for Ketones on p. 572). If the patient is unable to eat the normal caloric intake, he or she should continue to take the same dose of oral agents and/or insulin prescribed, but supplement food intake with carbohydrate-containing fluids such as soups, regular juices, and decaffeinated soft drinks. The health care provider should be notified immediately if the patient is unable to “keep anything down.” Patients should understand that medication for diabetes, including insulin, should not be withheld during times of illness because counterregulatory mechanisms in the body often increase the blood glucose level dramatically. Food intake is also necessary because the body requires extra energy to deal with the stress of illness. Extra insulin may also be necessary to meet the demand of illness. Hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar, can occur from too much insulin, a sulfonylurea, insufficient food intake to cover the insulin given, imbalances caused by vomiting and diarrhea, and excessive exercise without additional carbohydrate intake. Symptoms. Recognize and assess early symptoms of hypoglycemia; these include nervousness, tremors, headache, apprehension, sweating, cold and clammy skin, and hunger. If uncorrected, hypoglycemia progresses to blurring of vision, lack of coordination, incoherence, coma, and death. Children younger than 6 to 7 years may not have the cognitive abilities to recognize and initiate self-treatment of hypoglycemia. Treatment. If the patient is conscious and able to swallow, give 2 to 4 ounces of fruit juice, 1 cup of skim milk, or 4 ounces of a nondiet soft drink, or give a piece of candy such as a gumdrop. An alternative is to carry a glucose-containing product (e.g., Glutose gel, Dex4 Glucose tablets) and take as recommended when hypoglycemic. Repeat in 10 to 15 minutes if relief of symptoms is not evident. Do not use hard candy if there is a danger of aspiration. If the patient is unconscious, having a seizure, or unable to swallow, administer glucagon or 20 to 50 mL of glucose 50% IV. (People taking insulin should have a family member, significant other, or coworker who is able to administer glucagon.) Obtain a blood glucose level at the time of hypoglycemia, if possible. Hyperglycemia. Hyperglycemia (elevated blood sugar) occurs when the glucose available in the body cannot be transported into the cells for use because of a lack of insulin necessary for the transport mechanism. Hyperglycemia can be caused by nonadherence, overeating, acute illness, or acute infection. Symptoms. Symptoms of hyperglycemia are headache, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, dizziness, rapid pulse, rapid shallow respirations, and a fruity odor to the breath from acetone. If untreated, hyperglycemia may also cause coma and death. Glucose levels higher than 240 mg/dL and ketones present in the urine are early indications of diabetic ketoacidosis. Treatment. Treatment of hyperglycemia often requires hospitalization with close monitoring of hydration status; administration of IV fluids and insulin; and blood glucose, urine ketone, and potassium levels. Hyperglycemia usually occurs because of another cause; therefore, the problem, often an infection, must also be identified and treated. Prevention. The risk of hyperglycemia can be minimized by taking the prescribed dose of insulin or oral antidiabetic agent; adhering to the prescribed diet and exercise; reporting fevers, infection, or prolonged vomiting or diarrhea to the physician; and maintaining an accurate written record for the physician to analyze to determine the individual patient’s needs. Self-monitoring of blood glucose results and evaluation of urine ketones can provide the prescriber with valuable information to manage the treatment of the individual effectively. Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose

Drugs Used to Treat Diabetes Mellitus

Objectives

Key Terms

) (p. 560)

) (p. 560)

) (p. 560)

) (p. 560)

) (p. 562)

) (p. 562)

) (p. 562)

) (p. 562)

) (p. 562)

) (p. 562)

) (p. 562)

) (p. 562)

) (p. 562)

) (p. 562)

) (p. 562)

) (p. 562)

) (p. 563)

) (p. 563)

) (p. 563)

) (p. 563)

Diabetes Mellitus

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

FEATURE

TYPE 1 DIABETES

TYPE 2 DIABETES

Age (yr)

<20†

>40†

Onset

Over a few days to weeks

Gradual

Insulin secretion

Falling to none

Oversecretion for years

Body image

Lean

Obese

Early symptoms

Polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia

Often absent until complications arise

Ketones at diagnosis

Yes

No

Insulin required for treatment

Yes

No‡

Acute complications

Diabetic ketoacidosis

Hyperosmolar hyperglycemia

Microvascular complications at diagnosis

No

Common

Macrovascular complications at diagnosis

Uncommon

Common

DIABETES MELLITUS

PREDIABETES

A1C ≥6.5% in certified laboratory using DCCT assay

or

4.7%-6.4%

Symptoms of diabetes and a casual† plasma glucose level ≥200 mg/dL

or

N/A

Fasting plasma glucose level ≥126 mg/dL‡

or

100-125 mg/dL (IFG)

2-hour plasma glucose level ≥200 mg/dL during an OGTT

140-199 mg/dL (IGT)

Complications of Diabetes Mellitus

Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus

DISEASE

MONITORING PARAMETER

ADA THERAPEUTIC GOALS

AACE THERAPEUTIC GOALS

Diabetes

A1C

<7%†

<6.5%

Preprandial plasma glucose

70-130 mg/dL

<110 mg/dL

Postprandial plasma glucose

<180 mg/dL

<140 mg/dL

Hypertension

Blood pressure

<130/80 mm Hg

<130/80 mm Hg

Dyslipidemia

LDL cholesterol

<100 mg/dL

<70 mg/dL highest risk

<100 mg/dL high risk

Non-HDL cholesterol

<100 mg/dL highest risk

<130 mg/dL high risk

HDL cholesterol

>40 mg/dL in males

>40 mg/dL in males

>50 mg/dL in females

>50 mg/dL in females

Triglycerides

<150 mg/dL

<150 mg/dL

Weight

Weight Loss

BMI <25 kg/m2 (see pp. 339-340)

BMI <25 kg/m2 (see pp. 339-340)

Reduce weight at least 5%-10%; avoid weight gain

Drug Therapy for Diabetes Mellitus

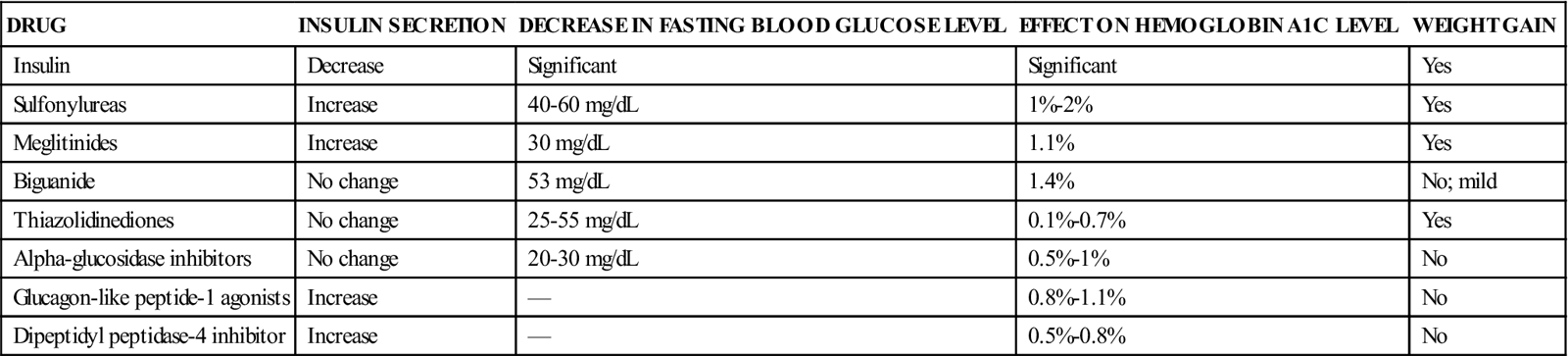

DRUG

INSULIN SECRETION

DECREASE IN FASTING BLOOD GLUCOSE LEVEL

EFFECT ON HEMOGLOBIN A1C LEVEL

WEIGHT GAIN

Insulin

Decrease

Significant

Significant

Yes

Sulfonylureas

Increase

40-60 mg/dL

1%-2%

Yes

Meglitinides

Increase

30 mg/dL

1.1%

Yes

Biguanide

No change

53 mg/dL

1.4%

No; mild

Thiazolidinediones

No change

25-55 mg/dL

0.1%-0.7%

Yes

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors

No change

20-30 mg/dL

0.5%-1%

No

Glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists

Increase

—

0.8%-1.1%

No

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor

Increase

—

0.5%-0.8%

No

![]() Nursing Implications for Patients With Diabetes Mellitus

Nursing Implications for Patients With Diabetes Mellitus

Assessment

Implementation

![]() Patient Education and Health Promotion

Patient Education and Health Promotion

36. Drugs Used to Treat Diabetes Mellitus

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree