CHAPTER 35. Youth Gangs and Hate Crimes

Cliff Akiyama

Youth gang violence has continued its upward trend nationwide, as one cannot turn on the television or radio or open the newspaper without hearing about another one of its victims. It was once thought that gangs only convened in selected areas, which left churches, schools, and hospitals as “neutral” territory. Unfortunately, this is a fallacy. Gang violence has poured into the schools, community centers, and hospitals. Throughout the country in urban, suburban, and rural communities, healthcare professionals are constantly being challenged by intramural shootings between rival gang members on a daily basis. Whether it is out in the community or in a hospital setting, as first-hand witnesses of youth gang violence, healthcare professionals represent a highly skilled community resource in the modern multiagency approach to help combat this new form of domestic terrorism. Youth gang violence has continued its upward trend nationwide according to the Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Furthermore, youth gangs have been identified in every single state. Nationwide, there are 24,500 gangs with a total gang membership of more than 750,000. The ethnic composition of these gangs includes 47% Latino, 31% African American, 13% Caucasian, 7% Asian, and 2% of mixed ethnicities (OJJDP, 2008).

The goals of this chapter are to (1) explain the organization of youth street gangs, (2) examine the historical evolution of gangs in the United States, (3) distinguish the behavioral differences and similarities between gangs, (4) compare and contrast activities of various gangs, and (5) determine gang implications for forensic nurses.

Getting started: what is a youth gang?

To discuss implications associated with youth gangs, we must first understand the term youth gang. The Virginia Gang Investigators Association (VGIA) has defined the term and has outlined the essential characteristics of a gang (VGIA, 2008). Part of the problem in the youth gang debacle across the nation is determining the definition of a youth gang. There are so many variations in the definition that it is hard for law enforcement agencies at the local, state, and federal levels to agree on one uniform definition; therefore, a definition of a youth gang is agency specific. In response to having multiple variations of the definition and no uniformity, statewide gang investigator associations such as the VGIA in conjunction with regional gang investigator associations such as the East Coast Gang Investigators Association (ECGIA) have developed their own definition. Their formally accepted definition is used by the member agencies in court proceedings and public venues.

A youth gang must be ongoing (associate on a continuous or regular basis). The youth gang could be formal or informal. Moreover, the youth gang must consist of at least three members and have a name, hand sign, and symbol that is identifiable. Another important element of a youth gang is that one of the primary objectives must be criminal activity (VGIA, 2008). So that it is not confused with various social groups such as fraternities, sororities, or social clubs, what differentiates a youth gang from other groups is its criminal activity. Law enforcement must define gangs and affirmatively determine which group is a gang. The public, defense attorneys, and the judiciary continue to challenge most declarations of what is and what is not a youth gang.

Gang Member Typologies

In every gang across the nation, there are various types of gang members ranging from hardcore to wannabe members. The most plentiful type of gang member is the active/regular gang member making up between 4% and 50% of the gang (Akiyama et al., 1997 and Virginia Gang Investigators Association, 2008). Regular gang members admit that they are in a gang when asked. They also have gang-related tattoos, are involved in gang-related crimes, and have a past history of gang activity. Associate/affiliate gang members make up 20% to 30% of the gang (Akiyama et al., 1997 and Virginia Gang Investigators Association, 2008). Associate and regular gang members also use hand signs to communicate with each other and to other rival gangs. Associate and regular gang members also write gang graffiti, wear gang-related clothing (colors), associate with known gang members, and are included in gang photos. What sets associates apart from regular members is that they are able to freely come and go in and out of the gang at will, making them great informants for law enforcement. The hardcore gang members, known as “OGs” (original gangsters), make up 10% to 20% of the gang and form the primary leadership arm of the gang group (Akiyama et al., 1997 and Virginia Gang Investigators Association, 2008). Hardcore gang members fit into all of the criteria listed for regular and associate members, but they are also involved in narcotics distribution. Furthermore, hardcore gang members are involved in violent gang activity from assaults, shootings, and robberies, to murder. Wannabes are the last group of gang member types. Wannabes make up less than 10% of the gang; however, they are extremely dangerous (Akiyama et al., 1997 and Virginia Gang Investigators Association, 2008). Although other gang member types have the potential to be extremely dangerous as well, the dangerousness of the wannabes lies in their motivation to be part of the gang to begin with. The wannabes need to prove that they are “down” and have “heart” (dedication) for the gang because in the gang hierarchy, wannabes are at the bottom. To be dedicated to the gang, the wannabes are instructed by the OG to prove that they have heart for the gang by performing a gang-related crime such as killing a rival gang member or committing a robbery or property crime such as burglary (Akiyama et al., 1997 and Virginia Gang Investigators Association, 2008).

In determining a gang member typology, it is important to use the strongest of initial criteria to classify a suspected gang member. For example, if an individual is documented for writing gang graffiti, wears gang colors, and admits that he or she is a gang member, this individual should be classified as a gang member. To list a person as a hardcore gang member, only one of the criteria for hardcore members needs to be met. Any evidence of heavy gang involvement must be thoroughly documented.

Manifestations of Youth Gang Violence: Why Are Our Children in Gangs?

Why would someone want to join a gang? The following are just some reasons.

Identity or recognition

This allows the gang member to achieve a level or status he feels impossible outside the gang culture. Most gang members visualize themselves as warriors or soldiers protecting their neighborhood from what they perceive to be a hostile outside world.

Protection

Many members join because they live in the gang area and are, therefore, subject to violence by rival gangs. Joining guarantees support in case of attack and retaliation for transgressions.

Fellowship and brotherhood

To the majority of gang members, the gang is a substitute for a family cohesiveness lacking in the gang member’s home environment. Many older brothers and relatives belong to or have belonged to the gang.

Intimidation

Some members are forced into joining by their peer group. Intimidation ranges from extorting lunch money to beatings. If a particularly violent war is in progress, the recruitment tactics used by the gang can be extremely violent, even to the point of murdering someone to cause others to conform.

Other factors

Other motivations for joining a gang include the need to make money, narcotics distribution, control over the environment, racial and cultural similarities, acceptance by peers, the loyalty and reward of just being part of the gang, recruitment, control of turf or territorial neighborhood, and common enemies. However, the most pervasive motive for joining a youth gang is a sense of finally belonging to a group that respects the individual.

African-American Gangs

African-American gangs are probably the most well known because of the media portrayal of gangs. The primary motivation of African-American gangs is earning money and narcotics distribution (Akiyama et al., 1997, Huff, 2001, Jackson and McBride, 2000, Klein, 1997, Leet et al., 2000, Schmidt and O’Reilly, 2007, Valdez, 2005 and Valdez, 2007). African-American gangs are divided up into “sets” based on geographic location; as a result, African-American gangs are territorial, meaning that they “claim” the neighborhood for which they often reside as belonging to that particular gang and no other gang can claim that territorial area (Egley et al., 2006, Franzese et al., 2006, Huff, 2001 and Leet et al., 2000). Furthermore, in an African-American gang, the individual is important, not the entire gang group (Akiyama et al., 1997, Huff, 2001, Klein, 1997, Leet et al., 2000, Valdez, 2005 and Valdez, 2007). An African-American gang member often will have a moniker or nickname, which is an arbitrary name given to a particular gang member that represents some characteristics that the individual wants to draw out (Leet et al., 2000). African-American gang members often wear identifying colors that indicate their gang affiliation, such as red clothing, shoes, and hats for Bloods and blue clothing, shoes, and hats for Crips (Akiyama et al., 1997, Huff, 2001, Klein, 1997, Valdez, 2005 and Valdez, 2007). Since the early 1990s, the Crips and the Bloods have been two of the most popular, polarized, and often glorified African-American gang groups in the United States, due in large part to the media portrayal of these two groups.

CRIPS

The Crips were founded around 1968 by Raymond Washington from the East Side (of Interstate-110 Harbor Freeway) in South Central Los Angeles, California. “Ray Ray,” as he was often known on the streets, originally formed a gang called the Baby Avenues, but after he got into a fight with another member, he decided to start his own gang called the Crips (Akiyama et al., 1997, Huff, 2001, Klein, 1997, Valdez, 2005 and Valdez, 2007). The gang derived its name from a popular television show that Washington enjoyed, called Tales from the Crypt. It was also rumored that Washington’s gang liked to “cripple” rival gangs (Leet et al., 2000). By 1971, Stanley “Tookie” Williams and Jamiel Barnes from the West Side of Interstate-110 Harbor Freeway joined Washington and the Crips (Huff, 2001).

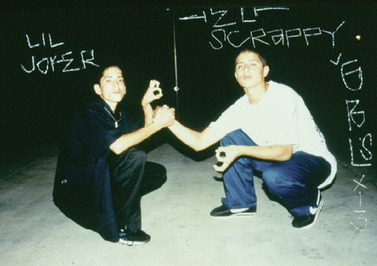

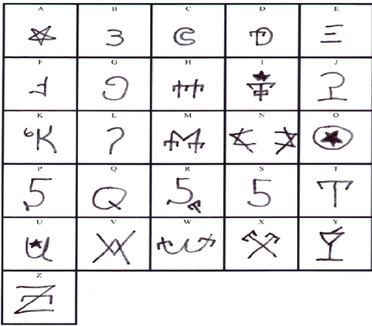

The Crips identify with the color blue because Raymond Washington attended Washington High School in South Central Los Angeles, California, where the school color was navy blue (Akiyama et al., 1997, Huff, 2001 and Leet et al., 2000) (Fig. 35-1). The Crips also display their colors on the left side. They also are allies with Folk Nation, an entirely separate gang located on the East Coast. It is important to note that Folk Nation is not a Crip gang, but the two are considered allies. The same is true with Bloods and People Nation. People Nation is not a Blood gang, but they too are allies. The Crips are rivals of the Bloods and People Nation, and they refer to the Bloods as “Slobs” or “Blobs” (Valdez, 2005). Graffiti is commonly referred to as the “newspaper of the streets” because of the information one can gain from reading it. Graffiti reveals the name of the gang, set, clique, and the specific members who have created it as a means to convey a message to their rivals (Akiyama et al., 1997, Huff, 2001, Jackson and McBride, 2000, Klein, 1997, Leet et al., 2000, Valdez, 2005 and Valdez, 2007). Crips write their alphabet in either blue or black (Leet et al., 2000).

|

| Fig. 35-1 |

Bloods/piru

Unlike the Crips, which constitutes only one gang, there are three types of Blood gangs: (1) Los Angeles, California, affiliated, (2) independent, (3) United Blood Nation (UBN), which are most commonly found on the East Coast.

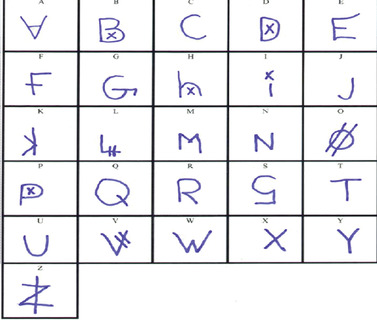

The Los Angeles–affiliated Bloods were founded around 1972 by Sylvester Scott and Vincent Owens from Centennial High School in Compton, California (Akiyama et al., 1997, Huff, 2001, Klein, 1997, Valdez, 2005 and Valdez, 2007). Scott lived on Piru Street and fought Crip gang members who had been expanding throughout South Central Los Angeles since 1968 (Leet et al., 2000). In general, the Bloods are smaller than the Crips but are more cohesive. The Bloods identify with the color red, and whereas the Crips display their colors on the left side, the Bloods display their colors on the right side (Valdez, 2005) (Fig. 35-2). The Bloods are allies with the People Nation gang and are enemies of the Crips and Folk Nation. The Bloods refer to Crips as “Crabs” (Valdez, 2005). Bloods write their alphabet in either red, white, or green (Leet et al., 2000) (Fig. 35-3).

|

| Fig. 35-2 |

|

| Fig. 35-3 |

United blood nation

The United Blood Nation (UBN) was founded in 1993, inside the prison system of New York’s Rikers Island, by Leonard “Deadeye” McKenzie, known as the Godfather of the East Coast Bloods (Huff, 2001, Valdez, 2005 and Valdez, 2007). McKenzie started the 9-Trey, set and Omar Porter (OG Mack) started the 1–8 Trey set of the UBN (Valdez, 2005), remembering that a “set” is based on geographic location for African-American gangs. For the UBN, selected numbers have specific meanings and are very important, since one will find number sets displayed as graffiti in public places or as body tattoos. UBN gang members will often use 031, indicating 0 for under blood nation, 3 for the number of fingers thrown up when they form the letter “b,” and 1 for one love under blood; 10/31 is also known as “Blood Day,” which is also the day of Halloween. The number 021 represents the 0 for fear of nation, 2 for new life under blood, and 1 for bloods together. The numbers 9 and 3 are also important to associate with UBN because of the sets that Leonard McKenzie and OG Mack started (Valdez, 2005).

Besides using specific number sets as graffiti or body tattoos, the UBN uses the following colors in its graffiti. Green indicates the money that United Blood Nations earns and the marijuana that the members smoke. Brown represents the dirt that they bury “Crabs” or Crips under (Valdez, 2005). The United Blood Nation also uses a five-pointed star in its graffiti, tattoos, and clothing; each point of the star represents a specific ideology of the UBN. The symbolism of the five-pointed star represents being African American, unity, communication, loyalty, and an understanding of the rules and regulations of the UBN (Valdez, 2005) (Fig. 35-4). Another symbol is the red, segmented apple. When an apple falls from the tree, it splits into four segments. These four segments represent the UBN’s rival gangs: the Crips, the Latin Kings (a Latino gang), and the Netas (a Latino gang), with the final segment representing all that oppose the Bloods, whether rival gangs or the community at large (Valdez, 2005). A bulldog and a set of dog paws are also popular with the UBN as seen in graffiti, tattoos, and clothing. The bulldog and dog paws are to give respect to the gang’s founder, Omar “OG Mack” Porter. A subtle indicator and another tribute to OG Mack is the Mack Truck logo on clothing, tattoos, or graffiti. It is often unknown to non-UBN gang members of their greeting to each other. UBN gang members greet each other by saying, “Soooo Wooooo,” which is a common greeting to other UBN gang members (Valdez, 2005). UBN and other Blood gangs often use the word “Damu” in verbal and written communication. Damu is Swahili for “blood.” UBN gang members will also spraypaint the letters “MOB” as graffiti, which means “Member of Blood” (Valdez, 2005 and Valdez, 2007).

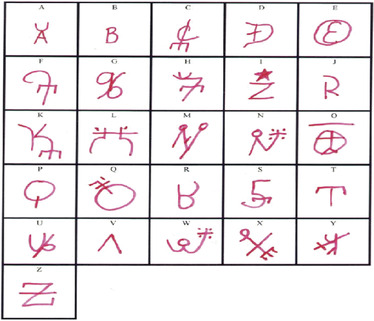

Folk nation

The Folk Nation gang was formed in late 1960s by David Barksdale, the founder of the Black Disciples (BD) set, and Larry Hoover, the founder of the Gangster Disciples (GD) set in Chicago, Illinois (Huff, 2001, Valdez, 2005 and Valdez, 2007). The Folk Nation adopted the Jewish Star of David as its main symbol in honor of David Barksdale (Huff, 2001, Valdez, 2005 and Valdez, 2007). The symbolism of the star represents love, life, loyalty, knowledge, wisdom, and understanding (Fig. 35-5). It is common to see the Star of David as graffiti for the Folk Nation. The Folk Nation has two mottos—“All Is One” and “Folk before Family”—to illustrate its ideology (Valdez, 2005). Not to be confused with the Bloods, the Folk Nation identify to the right side. The Folk Nation also uses a pitchfork in its graffiti, and each point represents mind, body, and the soul coming together in “One Nation” (Valdez, 2005) (Figs. 35-6 and 35-7). As mentioned previously, the Folk Nation is allied with the Crips. The Folk Nation also uses specific number sets, such as 7-4-14 (for the letters GDN, as in Gangster Disciples Nation) and 2-15-19 (BOS, which stands for “Brothers of the Struggle”) (Valdez, 2005).

|

| Fig. 35-6 |

|

| Fig. 35-7 |

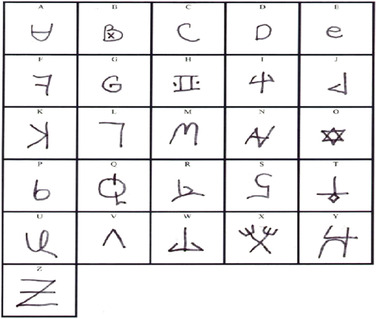

People nation

The People Nation gang was formed to counter the Folk Nation alliance. It was founded by Jeff Fort, of the Black P Stone Rangers set and later the El Rukn, along with Bobby Gore, of the Vice Lords set (Huff, 2001; Valdez, 2005, 2007). The People Nation uses a five-pointed star as its main symbol of identification. Moreover, members use the number 21 to represent the 21 original sets of the gang. The People Nation is also allied with the Bloods. Some other identifying features include the number 5. The People Nation displays its colors of red/black and gold/black (Vice Lords) to the left side (Figs. 35-8 and 35-9). Lastly, the People Nation has two mottos: “All Is Well” and “All Is All” (Valdez, 2005).

|

| Fig. 35-8 |

|

| Fig. 35-9 |

Latino Gangs

Latino gangs are motivated by a state of mind driven by La Raza, which translated means “for the race” (Akiyama et al., 1997, Huff, 2001, Jackson and McBride, 2000, Katz and Webb, 2006, Klein, 1997, Leet et al., 2000, Schmidt and O’Reilly, 2007, Thornberry et al., 2003, Valdez, 2005 and Valdez, 2007). It is important to note that La Raza is more of a cultural ideology than a gang-related one (Valdez, 2005 and Valdez, 2007). Nevertheless, Latino gangs are extremely territorial, and unlike African-American gangs, where the individual is important, for Latino gangs it is the gang as a whole that is important and not the individual (Akiyama et al., 1997, Huff, 2001, Leet et al., 2000, Valdez, 2005 and Valdez, 2007). To illustrate this point, when Latino gang members go to prison, they will be controlled by one of two prison gangs, depending on the geographic location of the prison: La Eme or Nuestra Familia (Huff, 2001, Leet et al., 2000 and Valdez, 2005). La Eme, otherwise known as the Mexican Mafia, is a prison gang originating in California and is considered the leadership arm of all Latino gangs in Southern California (Akiyama et al., 1997, Leet et al., 2000 and Valdez, 2005). The letter “M” in Spanish is pronounced “eme” and is the 13th letter of the alphabet. Consequently, throughout Southern California, Latino gangs will often call themselves by the city or area that they represent, followed by the number 13 to indicate “La Eme” or “Southern”, thereby giving respect to the Mexican Mafia. In Northern California, the Nuestra Familia, which is translated to mean “our family,” is the prison gang that controls every Latino gang north of Fresno and is often indicated by the number 14, representing the letter “N” for Nuestra and Northern (Leet et al., 2000 and Valdez, 2005).

At one time in the early 1960s, La Eme and Nuestra Familia were united as one prison gang called “La Eme”. It was not until the late 1960s when the two gangs began to separate to form two distinct prison gangs. This separation took place because the Latino gang members from Los Angeles in Southern California mocked fun of the predominantly migrant farm workers of Central and Northern California, thinking that the migrant factory workers in Los Angeles were better off financially and socially than the farmers of Fresno and Delano. However, these two Latino, predominantly Mexican-American prison gangs, have total control over the entire Latino street gang population throughout the state of California and Mexico—even Latino gangs who are rivals out on the street are, once incarcerated, under the control of either La Eme or Nuestra Familia, depending on geographic location (Leet et al., 2000 and Valdez, 2005). Once inside the California prison system, if any gang member or gang group does not comply with the demands and orders of La Eme or Nuestra Familia, there are serious consequences, even death to that specific gang member and all members of his gang. In fact, La Eme or Nuestra Familia will issue a “hit” on that gang, and if any Latino gang member sees a member of the gang that has the “hit” on it, that person is allowed to kill those targeted gang members immediately with no questions asked (Leet et al., 2000 and Valdez, 2005).

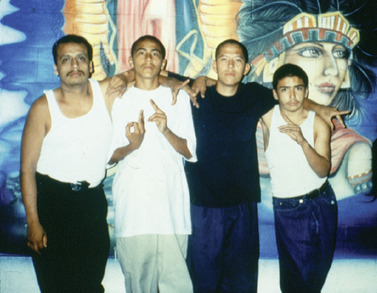

Latino gangs are very territorial and are often divided into cliques based on age, as opposed to the African-American gangs, which are divided by sets based on geographic location. An example of a Latino gang is the gang 18th Street. Membership in a Latino gang is not ethnically exclusive, especially in California. As a result, one will see other races and ethnicities in a Latino gang (Huff, 2001, Leet et al., 2000 and Valdez, 2005). Membership is, however, generational for some gang members, meaning that there could conceivably be three to four generations of gang members in one gang (Valdez, 2005) (Fig. 35-10). This characteristic is unique to Latino gangs, as one will not find multiple generations in an African-American, Asian, or Caucasian gang. All Latino gang members have monikers or nicknames, which is normally based on physical appearance (Fig. 35-11). Latino gang members are also known to have tattoos that indicate their gang affiliation. Some common tattoos are the three dots meaning “Mi Vida Loca” translated to mean “My Crazy Life” (Fig. 35-12). Other examples of tattoos in Latino gangs are the “Smile Now Cry Later” tattoo (Fig. 35-13).

|

| Fig. 35-10 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree