Warnings

A warning may be considered appropriate if the Case Examiners think the doctor’s behaviour or performance has fallen significantly below the expected standard, but not to such a degree as to indicate impaired fitness to practise. A common example would be drink driving. A warning will remain on the doctor’s registration for five years but subsequently will still remain in the public domain, albeit marked ‘expired’.

In practice, the doctor might have some limited opportunity to negotiate the wording of the proposed warning. However, if this outcome is unacceptable to him, there is a right in some circumstances to challenge it before an Investigation Committee. In a significant number of cases, the Investigation Committee decides not to issue a warning after all.

Undertakings

Undertakings are a set of written agreements restricting the doctor’s practice. They are likely to comprise supervision arrangements and are usually appropriate in cases concerning a doctor’s health or performance. They last indefinitely, until the Case Examiners in their discretion decide that they are no longer necessary.

If undertakings are accepted then, provided that they are not confidential, they are published on the doctor’s registration for as long as they are current. Even when no longer current, the inquirer will still be able to find out about them, as part of a doctor’s registration history.

If the doctor does not accept the undertakings, his case will be referred to the Fitness to Practise Panel entailing the risk of more severe sanctions.

Referral to a Fitness to Practise Panel and erasure

The most common kinds of case referred to the Fitness to Practise Panel concern substandard treatment. In theory, a single clinical mishap should not be sufficient to establish impaired fitness to practise. What primarily concerns the GMC is a pattern of poor performance. But it does sometimes happen that a doctor with an otherwise excellent clinical reputation can find himself before a Panel because of one case that went wrong. (See the example given below.)

A Fitness to Practise Hearing is conducted in the manner of a criminal trial. At the start of the hearing, for example, the doctor is required to stand while the charges against him are read out by the Panel Secretary. Unless the hearing concerns confidential matters, such as those relating to the doctor’s health, it will normally be in public. A significant difference is that, since 2008 the doctor no longer has the relative protection of the criminal standard of proof, ‘beyond reasonable doubt’. Now the GMC prosecutors only have to prove the case on the lesser standard of ‘on the balance of probabilities’, that is, the allegations are more likely to be true than not.

The hearing itself will usually take place in Manchester and will be before a Panel of at least three people (in longer cases, it should be five). Doctors in this situation are often surprised that only one member of the Panel must be a doctor, and even then, not necessarily from the same speciality.

At the end of the hearing, the Panel will decide:

Even in cases where Fitness to Practise is found not to be impaired, the Panel can be asked to consider whether to impose a warning on the doctor’s registration, as an indication of its disapproval of his conduct.

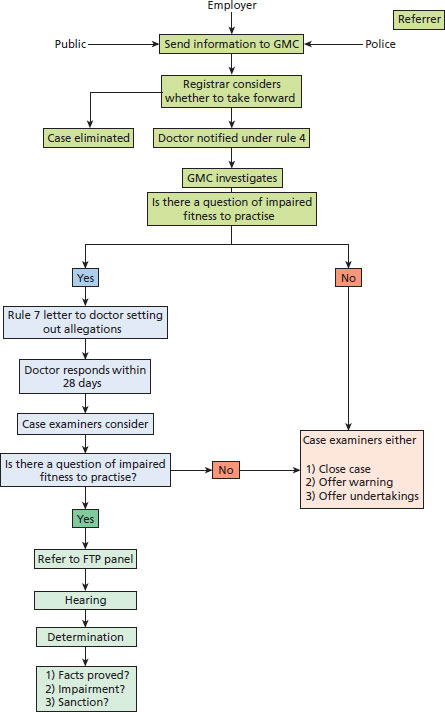

It is important to appreciate that when considering whether a doctor’s fitness to practise is impaired, the Panel must look not just at past failings but also at the doctor’s present and future fitness to practise. A doctor who can demonstrate he understands his past failings (i.e. he has insight) and has taken action to improve his performance (i.e. remediation) may well not be impaired after all. Table 3.2 shows the outcomes of Fitness to Practise Panels in 2010. The diagram at Figure 3.1 summarises the GMC’s fitness to practise procedures.

An example from general practice

A GP in a rural practice appeared before the Fitness to Practise Panel of the GMC facing allegations that he had deliberately hastened the death of an already dying patient by administering a 100 mg injection of diamorphine. It was also alleged (and admitted) that his actions placed the patient at risk of developing fatal respiratory depression.

The patient had terminal lung cancer and had been discharged home from hospital to die. In the last few days of his life, he was extremely agitated and distressed. His family and the nurses were exhausted.

The GP decided it was appropriate to administer a 20 mg bolus of diamorphine. However, the practice dispensary only had 100 mg ampoules available. The GP said he intended to only draw 20 mg into the syringe, but in the event he found that he had administered the whole 100 mg. He said this was a mistake and he found it difficult to explain how it had happened.

The Panel had to decide what the GP’s intentions were. They took into account the doctor’s own account of events as well as the accounts of others. It noted, for example, that the GP told the family later that day that he had given more diamorphine than he intended. He also spoke to the nurses, but their recollections of exactly what he said were somewhat conflicting.

He told his practice manager and the PCT he had made an error, but it was not clear that that was what he told the Coroner’s officer. The GP’s note in the records stated that he wanted the patient to die in peace. This could be interpreted as evidence of a deliberate intention to hasten death.

It was his previous good character and the fact that the GP did not seek to hide the facts which in the end persuaded the Panel that, on the balance of probabilities, he did not intend to hasten death when he gave the injection. They said that the stressful, unusual and extremely difficult circumstances he found himself in meant that his practice slipped from its usual high standard and he had made a mistake rather than committed a deliberate act.

Considering the question of whether, on the admitted facts of giving the injection and then not taking any steps to reverse its effects, the GP was guilty of misconduct, the Panel concluded that his error was so serious as to indeed amount to misconduct. This was because diamorphine is a controlled drug which requires great care in its administration. The public expects doctors to administer correct dosages. Then the Panel went on to consider whether the doctor’s fitness to practise was impaired by reason of his misconduct. It took into account his attitude and insight as demonstrated by his oral evidence and by the testimonial letters which were put before it. In particular, the doctor had had a mentor at the PCT since the events in question, who wrote saying that he had reflected on the events, had suggested ways in which he could help other doctors in a similar position and had spoken to local GP appraisers about the case. Evidence was also submitted that he had attended courses in palliative care at hospices, attended focus groups and engaged in reading on the subject.

The Panel bore in mind that his record was unblemished up to that point. They decided that, although guilty of misconduct, his fitness to practise was not impaired. Finally, the Panel considered whether to impose a warning on his registration. It decided that, in view of the seriousness of the matter and the need to uphold the public’s confidence in the medical profession, it was necessary to send a message to the profession and the public that his misconduct was not acceptable. A warning was therefore imposed on his registration for a period of five years (although, even after five years, the warning was still on record as a matter of history, albeit not published for all to see on the list of medical practitioners).

The GMC in future

Two significant developments to GMC regulation are in the pipeline.

(a) Revalidation

This concept has been much discussed since the Shipman Inquiry highlighted what has been termed ‘a regulatory gap’ between a doctor’s employer and the GMC.Some doctors [are] judged as ‘not bad enough’ for action by the Regulator, yet not ‘good enough’ for patients and professional colleagues in a local service to have confidence in them. There is thus a significant ‘regulatory gap’ and it is this gap that endangers patient safety. (DoH, 2006)

There were a number of public consultations on the concept of ‘revalidation’ as a means of closing this ‘regulatory gap’. The first step towards this process was the requirement since November 2009 that a doctor must not only be registered to practise but must also have a licence to practise. Without that licence, it is a criminal offence to practise medicine, write prescriptions, sign death certificates or undertake any other activities which are restricted to doctors holding a licence.

In late 2012, the GMC will open the process of ‘revalidation’ whereby every five years a doctor’s licence to practise must be renewed. To do that, the doctor must be able to demonstrate to his ‘Responsible Officer’ that he is up to date and remains fit to practise.

It is envisaged that every organization providing healthcare will nominate a senior practising doctor to be the GMC’s Responsible Officer. He is likely to be the organization’s Medical Director. He has statutory duties to the GMC and so will be the bridge crossing the gap between local clinical governance and the GMC. His duties will be to ensure that there are adequate local systems for responding to concerns about a doctor, to oversee annual appraisals for all medical staff and to make recommendations for revalidation. He will write a report on the suitability of doctors in his organization for revalidation, based on their annual appraisals over the previous five years, and on any other information drawn from clinical governance systems. Where, as a result of his report, the GMC’s Registrar considers withdrawing a doctor’s licence, he will inform the doctor and give him 28 days to make representations about it. The Registrar must take those representations into account before making a decision. If he does then decide to withdraw the licence, the doctor will have the right to appeal to a Registration Appeals Panel. Equally, the GMC may well decide to put the matter through its Fitness to Practise Procedures.

What does this mean in practice for the individual doctor? He must keep a portfolio of supporting information for his annual appraisal, showing how he is keeping up to date, evaluating the quality of his work and recording feedback from colleagues and patients. The Royal Colleges for the different medical specialities will advise on the kind of material to be compiled.

The appraiser may also decide to use confidential questionnaires of patients and colleagues.

The GMC has warned practitioners that appraisal discussions will be more than a mere question of collating material. ‘Your appraiser will want to know what you did with the supporting information, not just that you collected it.’ The doctor will be expected to reflect on how he intends to develop and modify his practice.

Discussions at appraisals may be guided by the principles of the GMC’s Good Medical Practice, which have been helpfully reduced into what are called The ‘Four Domains’, each domain having three ‘Attributes’.

The theory is that a doctor who falls short of any of the required Twelve Attributes should be picked up by the clinical governance system during the five-year licence cycle, and given the appropriate support, so that his licence will be renewed at the end of the cycle.

The GMC says this about the closure of the ‘regulatory gap’:

For the first time, employers, through Responsible Officers, will be required to make a positive statement about the Fitness to Practise of the doctors they employ. With their new responsibilities for overseeing revalidation, employers are more important than ever in promoting high standards of medical practice.

Critics of the scheme say that a revalidation scheme based on the collection of papers and an annual appraisal will not effectively detect rogue doctors. They say that Shipman would have had his licence renewed. Critics also say that the scheme places too much power and influence in the hands of one person, the Medical Director/Responsible Officer, a feature which, they say, will draw the GMC into the politics of the workplace.

(b) Consensual disposal

Ever since the procedural reforms of 2004, the GMC, sensitive to the criticism that doctors only ever look after their own, has placed a lot of emphasis on the transparency of its procedures. Decisions about impairment and about sanction are made in public at the conclusion of a public hearing (unless the issues under consideration concern a doctor’s health in which case the hearing is in private). This is intended to maintain public confidence in the profession.

However, what has tended to happen is that after several days of exhausting and stressful evidence, although facts may have been proven against the doctor, it turns out that he can show insight and remediation. His Fitness to Practise may have been impaired at the time, but it is now no longer impaired. In that case, there is no finding of impairment and the worst that can happen is a warning. The general practice example given above is a case in question. Was the hearing worth it?

Add to that the rising number of complaints, the rising number of hearings every year and the rising cost, and we find that the GMC is now thinking about dealing with at least some of its cases in a different way. The phrase ‘consensual disposal’ has been coined for the suggestion that the GMC and the doctor engage in some discussion about agreeing a sanction without the need for a hearing or witnesses. But would this kind of process undermine public confidence and create a perception of deals done ‘behind closed doors’?

A recent consultation showed a large measure of support for the idea in principle. It was thought it might be most suitable for cases where there was no significant dispute about the facts. But it was also considered that there would be some cases in which such a process would be inappropriate, although it was difficult to establish what kind of cases these might be. More detailed proposals on the idea are now being developed by the GMC.

7 The role of the doctor

It is a professional requirement of the GMC’s Good Medical Practice that all doctors must assist with investigations. A doctor who is asked to provide a written statement of events as part of any investigation – for example, a Coroner’s inquiry – must co-operate. Equally, he must be very conscious that what he writes now may be referred to in later proceedings. He therefore needs to be accurate. If there is any risk of trouble in the future, a doctor would be well advised to contact his MDO and ask for his proposed statement to be looked over by a medico-legal adviser.

Witness statements

A doctor who is asked to prepare a witness statement concerning the care of a patient should always be provided with a copy of the relevant set of patient records to assist him.

Although a witness statement should be prepared as soon as possible after the event, so that the details are fresh in the mind, the doctor should not allow himself to be rushed. Accuracy is more important.

Here are some tips on writing a well laid out and clear witness statement:

Formal requirements

- Write on one side of the paper only

- Type the statement and bind it using one staple in the top left-hand coroner. Have a decent left and right margin and double space the document.

- Use a heading to orientate the reader e.g. Statement of Bob Smith following the death of Augustus Clark on E Ward at Pilkington Hospital on 22 November 2006.

- Number the pages and identify the statement in the top right-hand corner of each page, e.g. Page 2 Witness Statement of Bob SMITH.

- Number paragraphs and appendices.

- Refer to documents and names in capitals and express numbers as figures.

- Attach copies of protocols or other documents referred to, e.g. staff rota or clinical observations chart.

- Sign and date it.

- End with a statement of truth: ‘I believe that the contents of this statement are true.’

- Spell-check the statement.

Content

- Before starting, decide ‘What are the issues?’

- Write a chronology. This will provide the structure.

- In the first paragraph, witnesses should set out who they are, their occupation and where they work (currently and at the time of the incident). It is important to orientate the reader, so a short CV is helpful. In more complex cases a fuller CV can be appended.

- There should be a main heading and subheadings.

- Use short sentences (a sentence that goes on for more than 2 lines is too long) and paragraphs (aim for about 3 sentences per paragraph).

- Do not stray into an other witness’s evidence.

- Statements should contain no retrospective opinions, only contemporaneous opinions. Avoid statements like ‘I thought for years this was going to happen’. Contemporaneous opinions should be backed up by facts. When stating a professional opinion, e.g. a diagnosis, explain the thinking behind the opinion.

- Do not use jargon. If technical terms have to be used, consider the use of a glossary and/or diagrams. Try to make the statement accessible to a non-clinician.

- Avoid pseudo-legal language such as ‘I was proceeding in a northerly direction’

- Identify individuals as they are introduced to the narrative

- Ambiguous expressions such as ‘I would have done such and such’ should be avoided. If the doctor does not recall what he did, he should say so clearly. If, based on his normal practice, he believes he did such and such, then this should be made clear too.

Presenting oral evidence

Having looked at negligence claims, disciplinary hearings, Coroner’s hearings and GMC hearings, it is appropriate to say a few words about how to give evidence. For the way a witness presents his evidence affects the weight given to it by the Court/Inquiry/Tribunal.

Remember that a witness’s role is to assist the Tribunal. He is not there to argue with the barrister.

The barristers may try to draw witnesses into an argument. They may also use other techniques to disconcert them, such as moving between multiple documents. Once the witness recognizes that they are just techniques, they can watch out for them and so remain in control.

The lawyer is only doing his job. Witnesses have to separate themselves from the evidence and not get angry.

Before giving evidence, witnesses should:

- re-read and think about all the evidence including the records, protocols, national guidelines and professional standards;

- re-read witness statements and Court/Inquiry documents (if appropriate) and ask their lawyer to explain anything they do not understand;

- check with the lawyers whether there are any other documents they would like the witness to read, such as clinical studies;

- tell the lawyers about any mistakes or omissions in the witness statement;

- visit the courtroom beforehand; ask the Court for a tour;

- if possible see the Court/Inquiry ‘in action’ beforehand;

- plan the route to the hearing, arrange where to meet everyone and work out what to wear;

- exchange telephone numbers with the legal team;

- put the Court telephone number into their mobile phone;

- practise taking the oath and giving their credentials.

At the hearing:

- report to the reception desk where you will need to register;

- be prepared to come into contact with family members and media representatives;

- keep conversations to a minimum and nonverbal communications appropriate;

- on entering the courtroom sit down and do not talk;

- stand up when the judge/panel arrives and then be seated;

- the proceedings will be recorded; be prepared to speak clearly and slowly;

- pause before answering any questions;

- listen carefully to the question;

- deliver your answers to the judge/panel; the best way to ensure this is to stand with your feet facing the judge/panel and turn from the hips to take questions from the lawyers;

- try to keep answers to questions brief and to the point;

- try to eliminate passion from your answers.

No-one, not even a seasoned expert witness enjoys the stress of giving evidence. But to do so is part of a doctor’s professional duty.

8 Emotional repercussions

Many doctors take criticism extremely personally, even if the complaint is relatively straightforward and can be put to rest without too much difficulty. Each doctor will react differently. The experience may leave him feeling scarred. Some may find that the complaint takes a physical toll on them. Some may even leave the profession altogether. Others seem able to take a relaxed attitude, at least on the surface.

Stress associated with complaints can lead to anxiety, depression and on rare occasions even suicide. It can impinge on the doctor’s work and family life. People deal with stress in different ways, but talking to colleagues, friends and family can help. The solicitor and the medico-legal advisor at a doctor’s MDO are on hand to help and to listen to concerns. They are there to provide emotional support as much as legal advice.

The GMC has produced a useful leaflet, available on line, called, ‘Your Health Matters’ providing doctors with advice about looking after their own health. It lists numerous sources of support for doctors experiencing stress or depression.

The British Medical Association also offers a 24-hour counselling service with the opportunity to talk to a counsellor or a doctor on 08459 200 169. A doctor may need the help of a GP, psychotherapist or psychiatrist. Some Deaneries, such as the London Deanery, offer free emotional support and psychotherapy to doctors suffering from stress or emotional ill health. Doctors can self-refer to this service. In London the service (called MedNet) is run by Consultant Psychiatrists (020 8938 2411). There are therefore many sources of help for the doctor suffering from stress or anxiety.

9 Conclusion

We hope that this section has clarified the procedures which may come into play after a medical error.

The reader may well be daunted by the number and complexity of the mechanisms involved. However he should take heart. Although dealing with a complaint may be very stressful there is always high-quality professional help available. Our advice is to make full use of it.

The other point to make is that error is part of the human condition. In 2011 there were 8781 complaints to the GMC and it is thus not uncommon for a doctor to be referred. All doctors make mistakes, even excellent ones and even those who sit on GMC Fitness to Practise Panels. Doctors who make mistakes can become better at their jobs, and go on to have successful and productive careers. The key is to reflect on errors and pay heed to any lessons that can be learnt.

Reference

Department of Health (2006) Good doctors, safer patients: Proposals to strengthen the system to assure and improve the performance of doctors and to protect the safety of patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree