are no longer lower than the OECD average, and are increasing (AIHW 2006; The OECD Health Project 2004).

Relative to the United States (US), the United Kingdom (UK), Canada and New Zealand (NZ) (countries most commonly used by Australian analysts for comparison) Australia has the best overall health outcomes, and exceeds the US and ranks reasonably closely with the others on equity. Australia’s health system is less costly than that of the US, but is substantially more expensive than those of the UK and NZ. For Australians covered by health insurance, access to doctors and emergency departments is better than in the other countries, except NZ, and access to elective surgery is better than in the other countries, except the US.

Some of these results reflect, in part, the balance struck in the Australian system between choice and equity, with incentives to supplement access via Medicare with private health insurance cover. The US does not have universal coverage but relies heavily on private insurance arrangements, while the UK, NZ and Canada do not have incentives for supplementary private insurance.

Australia’s most serious health policy problem is Indigenous health. Indigenous people’s life expectancy is around 17 years less than for other Australians, a larger gap than that between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in the US, Canada and NZ (ABS and AIHW 2005, AIHW 2006).

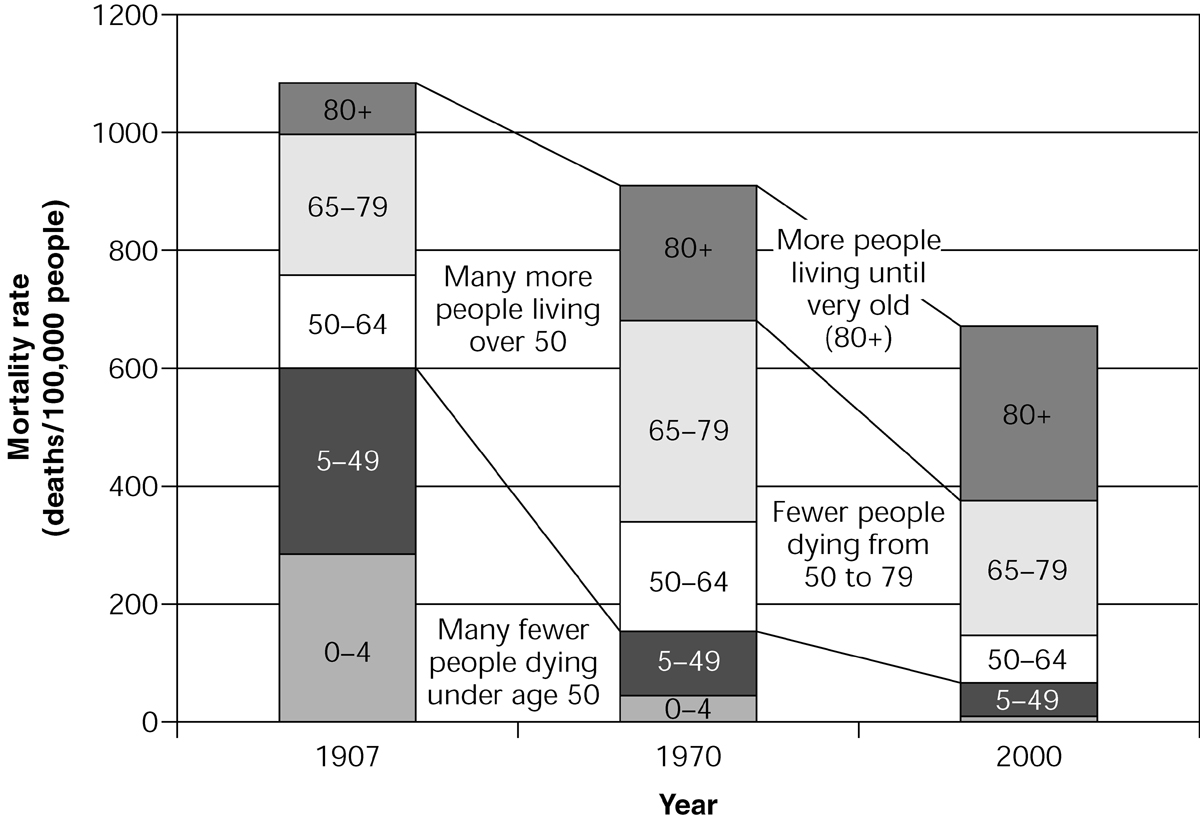

Second to Indigenous health, the biggest challenge for Australian policy makers is to address the consequences of major successes: that Australians are living a lot longer today, and are not dying as rapidly as they used to after being diagnosed with, for example, heart disease or cancer. Figure 3.1 illustrates historical changes in Australian mortality rates.

The increase in life expectancy in Australia from 1907 to 1970 reflected successes in reducing child mortality and mortality overall, so that many more people reached the age of 50, but the increase in life expectancy since 1970 has been dominated by gains in ensuring that those who reach age 50 live a lot longer on average after that point. Life expectancy is still increasing at around 3 or 4 months every year. One of the consequences of this is the increased number of frail aged people. There are also many more people who have survived the onset of heart disease or cancer or other diseases, but require some ongoing care regime to ensure they can live with reasonable independence and quality of life.

The AIHW has estimated that about 80% of the burden of disease in Australia is now related to chronic disease (AIHW 1999, 2004a). A central question now is how well the Australian health system performs in managing chronic disease and the needs of the increasing numbers of the very frail aged.

There is evidence that improvements could be made (AIHW 2004a, 2004b). There is a high rate of potentially avoidable hospitalisations for chronic conditions. The care of the frail elderly who need some hospital care could be better managed; too many of them go to hospital too often and there are too many elderly people in hospitals awaiting residential aged care. Step-down and rehabilitative care has been substantially cut in the past decade or so. Despite incentives for general practitioners to coordinate care plans for the chronically ill, the take-up of the incentive has until recently been weak, and there is patchy support for those patients needing allied healthcare and advice. The increasing incidence of obesity and diabetes, in particular, suggest we are investing too little in preventive health strategies.

A more integrated approach to healthcare is needed. Australia is not performing as well as it should on care for the chronically ill and is ranked at the bottom of the five nations surveyed by the Commonwealth Fund (2005). The structure of the Australian health system is almost certainly contributing to this poor performance. The structure involves a series of distinct programs related to particular providers and products: the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) reimbursing patients for visits to doctors; the Australian Health Care Agreements, under which states fund public hospital care for public patients; the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) subsidising prescription medicines; the Residential Aged Care program subsidises care in nursing homes and hostels; and the Health and Community Care (HACC) program (and the Australian government’s aged care packages) subsidising community care services for people living at home. There are also the federal government’s incentives, including the private health insurance rebate, for private health insurance for hospital and related specialist medical care services. The problems associated with this program structure are exacerbated by the different sources of funding, adding to incentives to sharpen the boundaries.

Apart from obstructing the patient orientation essential for appropriate care, in particular of the frail aged and those with chronic illnesses, the structure constrains the overall efficiency of the system, and contributes to its rising costs. Australia has an international reputation for expertise in applying cost-effectiveness requirements for listing and pricing pharmaceuticals; this has been expanded to medical services. There have also been successes in using casemix-based purchasing to drive efficiencies in the hospital sector, though there has been some reluctance to extend the use of casemix and other sophisticated purchasing techniques and competition. Australia’s complex funding arrangements for public and private hospital care also produces an uneven playing field and inappropriate incentives for hospitals and private insurers.

Perhaps the most significant contributor to inefficiency is not the lack of technical efficiency within particular program areas, but allocative inefficiency where the balance of funding across programs (including public health in particular) is not giving best value, and the inability to shift resources between programs at local or regional levels. Allocative efficiency has attracted considerable attention overseas since a study comparing the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) and Kaiser Permanente’s system in California (Feachem et al. 2002). The study suggested the NHS might perform better if it allocated more of its resources to primary care and information technology. However, it is likely that the problem in Australia is greater than in the UK, because of a stronger demarcation of programs, particularly through having different funders with incentives for cost shifting and blame-shifting, and the UK’s greater experience with integrated purchasing mechanisms such as general practitioner (GP) fundholding and primary care trusts.

Cost shifting and blame-shifting also have direct costs. Claims of substantial bureaucratic costs involved in overlapping activities between the Commonwealth and the states and territories (Dwyer 2004) are greatly exaggerated: the whole Commonwealth health department’s operating costs in 2005–06 amounted to only $569 million. But a great deal of political and bureaucratic attention is given to this game-playing instead of seeking to improve the effectiveness of health services.

In summary, the key structural problems in Australia’s health system are:

- the lack of patient-oriented care that crosses service boundaries easily with funds following patients, particularly those with chronic diseases, the frail aged and Indigenous people

- allocative inefficiency, with the allocation between different types of care, and between care and prevention, not always achieving the best health outcomes possible, and with obstacles to shifting resources for individuals or communities to allow different mixes reflecting different needs.

These structural problems have been reinforced by poor use of information technology, which could support continuity of care, better identification of people at risk, greater safety and more patient control. They have also been exacerbated by the poor use of purchasing and competition, with a reluctance to use sophisticated approaches to ensure best access to effective services at reasonable cost, and an ‘uneven playing field’ in the area where competition is most encouraged.

REFORMING THE SYSTEM

There have been many sensible, incremental reforms over the past 15 years to address structural problems in the Australian health system.

Perhaps most importantly, there has been a gradual strengthening of primary care, which is central to a more integrated approach. This has come through establishing GP divisions and the progressive extension and complementing of MBS items to incorporate funding for practice support, incentives for preventive health, such as immunisation and cancer screening, and care coordination and planning. Most recently, funding has been allocated through general practice of ancillary health services for particular groups of patients, such as the mentally ill. GP funding is now essentially through blended payments, including both fee-for-service and funding for the patient population.

Increased incentives have been offered to practice in rural areas, where healthcare services are less plentiful. Some flexible funding has been provided for community health services, either directly by the Commonwealth to GPs and GP divisions, or in cooperation with states and territories; for example, for multi-purpose health service centres.

Additional funding has also been provided to Indigenous communities for primary healthcare, recognising their lack of direct access to MBS and PBS. The coordinated care trials in particular achieved substantial improvements in services to participating communities, and easier access to PBS funds for remote communities has also contributed to improvements in healthcare access (Department of Health and Ageing 2001, 2006a).

Increased emphasis on community aged care services and more flexibility in aged care funding through ‘ageing in place’ has also improved the responsiveness of the system to older patient needs and preferences (Department of Health and Ageing 2004).

Steps have also been taken to improve and link information support (see also Ch 11). Legislative prohibition of linking the MBS and PBS has been removed; pharmacists have (with government support) developed better patient records that support both safer use of medicines and cost reduction for both patients and government; GPs are also increasingly using electronic patient record systems after a low take-up of government support for some years; and hospital discharge information is more frequently passed on to GPs, even if rarely done electronically. The Health Connect initiative, aimed to establish the standards necessary to allow easier transfer of patient data and to establish a national system of electronic health records, is slowly making progress.

There have also been improvements in cost controls using forms of purchaser–provider arrangements. Some states have developed sophisticated approaches to hospital financing using casemix, following federal government investment in the model. The Australian government has entered into increasingly robust agreements with the medical profession on pathology and radiology funding, even experimenting with a competitive approach to the funding of MRI services in country areas. The Australian government’s use of cost effectiveness in listing and pricing PBS items has also incorporated more sophisticated approaches in complex cases, such as the use of price-volume agreements to share risks. And cost effectiveness is slowly being extended to the MBS.

With the exception of the Veterans’ Affairs portfolio, where the Australian government, as the single funder, has facilitated a substantial review of the balance of care services for veterans, mechanisms to encourage better allocational efficiency have not so far been particularly successful. The 1998 Australian Health Care Agreements (AHCA) included a provision to ‘measure and share’ options for shifting resources between the federal government and a state or territory where it was evident there would be efficiency and effectiveness gains. After 5 years, progress was made in only one state on one initiative: the provision of drugs on discharge from hospitals. There is little evidence of much progress since, despite regular statements of cooperation.

In other areas, the continued division of financial responsibilities encouraged action that was neither in the interests of patients nor in the interests of overall efficiency. The number of rehabilitation beds in state and territory hospitals declined, notwithstanding the ageing population and a substantial increase in admissions by older people. Australian hospitals also continue to exhibit a different approach to emergency departments than do their overseas counterparts, with few having an area offering appointments for people with less urgent medical needs. Instead, such patients are triaged along with urgent cases, and may end up waiting hours for attention.

The division of responsibilities also continues to encourage politically inspired initiatives that duplicate and complicate service provision. The HACC program, jointly funded by the Australian and state or territory governments, has proven to be difficult to reform into a standardised package of services based on assessed need, and in recent years the Australian government has introduced and extended its own program of aged care packages.

Nonetheless, there have been good incremental reforms, and more are still emerging. The 2006 initiatives for mental healthcare added further to the role and capacity of primary care services, responding to the yawning gap in mental health services that developed after the well-intentioned deinstitutionalisation policies of the 1980s (Department of Health and Ageing 2006b). Changes to the regulation of private health insurance should also improve competition between funds, and encourage them to consider out-of-hospital care where that would be more efficient and effective (Abbott & Minchin 2006).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR POLICY DEVELOPMENT

Given the effort required and risks involved in systemic reform, it is understandable that most attention continues to be placed on incremental reform options.

There is a risk, however, that incremental reform without a clear sense of direction will be mere ‘ad hocery’. To avoid this risk, incremental measures need to meet some broad tests:

- coherence with a national policy framework that incorporates principles of universal access to quality services, a patient-oriented approach that facilitates continuity of care, efficient service delivery with a considerable degree of patient choice and provider competition, and a focus on safety, effectiveness and cost effectiveness

- progress towards, or at least not moving further away from, integrated service provision

- contribution to making systemic reform (sometime in the future) easier, not harder.

- progress towards, or at least not moving further away from, integrated service provision

In addition, initiatives need always to deliver tangible improvements in services to patients or tangible gains in efficiency and cost effectiveness (and preferably both), in order to attract the support of the key stakeholders in the system: patients and professional service providers. Incremental measures that would clearly meet the tests identified above are set out in Box 3.1.

BOX 3.1 INCREMENTAL MEASURES TO REFORM THE HEALTH SYSTEM

- Renegotiating the Australian Health Care Agreements (AHCA) to promote more forcefully the agenda of cooperation at the program boundaries where reallocation of resources would improve care effectiveness and efficiency (e.g. rehabilitative care, discharge services, outpatient services and emergency departments), and to require all states and territories to apply casemix processes to funding hospitals.

- Restructuring responsibilities for out-of-hospital aged care services, so that the national government would have full and direct financial responsibility, the states and territories having full and direct responsibility for people under 65 with disabilities; the Australian government would then have the opportunity to pursue the reform agendas it has been foreshadowing for some years in the areas of community services based on assessments and high-care residential services allowing more choice.

- Commencing to build a regional infrastructure based on state- and territory-defined regions, starting with information through regional health reports prepared independently by the AIHW on the health of the relevant population, the utilisation of health services, and the total government spending on the regional population; this to be complemented by relating current state, territory and federal government regional planning arrangements (e.g. for hospitals and aged care services, and by GP divisions) to each other, drawing upon shared information, including the AIHW reports.

- Establishing a new Australian government primary care funding program available to regions with low levels of government health expenditure, for highly flexible use to strengthen access to primary care services. This might include new incentives to attract GPs, and funding nurse practitioners and allied health professionals. The funds could be made available through GP divisions or other regional arrangements determined by the Australian government.

- A long-term program to expand funding for Indigenous communities on a broadly similar basis: increasing primary care funding to the average level across Australia, adjusted for the higher costs of care delivery in remote and regional areas.

- Restructuring responsibilities for out-of-hospital aged care services, so that the national government would have full and direct financial responsibility, the states and territories having full and direct responsibility for people under 65 with disabilities; the Australian government would then have the opportunity to pursue the reform agendas it has been foreshadowing for some years in the areas of community services based on assessments and high-care residential services allowing more choice.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree