Section 3 Identification of patient problems

3.1 Holistic approaches to care

The recognition that patients are whole people and cannot be viewed in reductionist terms.

The recognition that patients are whole people and cannot be viewed in reductionist terms.

The whole cannot be understood merely by isolating and examining its parts.

The whole cannot be understood merely by isolating and examining its parts.

That nursing moves beyond disease management and requires that the nurse and patient collaborate to promote health.

That nursing moves beyond disease management and requires that the nurse and patient collaborate to promote health.

The environment within which individuals live must be included.

The environment within which individuals live must be included.

That people live in cultural and social communities.

That people live in cultural and social communities.

People have networks of relationships with others, most notably within the family.

People have networks of relationships with others, most notably within the family.

That individuals have sexual needs as well as physical, psychological and social needs.

That individuals have sexual needs as well as physical, psychological and social needs.

Nursing process

Assessment – all the patient information is gathered and examined to obtain all the facts necessary to determine the patient’s health status and identify problems.

Assessment – all the patient information is gathered and examined to obtain all the facts necessary to determine the patient’s health status and identify problems.

Goal setting takes place after patients have been assessed. Goals are sometimes referred to as aims of nursing, objectives, desired end results or expected outcomes of care. To be useful, goals need to be stated in a clear and precise way. One way of achieving this is to state them in behavioural terms – what you would expect to observe, hear or see demonstrated if the goal is achieved. In other words, you set a measurable response which would be expected from the person for whom the goal is set and subsequently observe whether it has been achieved. Involvement of patients in goal setting can result in more effective achievement and greater satisfaction for those providing healthcare. However, not all patients are able to make decisions for themselves nor to be full partners in setting goals, such as those who are unconscious, confused or mentally handicapped. In these instances relatives or friends may become involved in establishing appropriate goals with nurses.

Goal setting takes place after patients have been assessed. Goals are sometimes referred to as aims of nursing, objectives, desired end results or expected outcomes of care. To be useful, goals need to be stated in a clear and precise way. One way of achieving this is to state them in behavioural terms – what you would expect to observe, hear or see demonstrated if the goal is achieved. In other words, you set a measurable response which would be expected from the person for whom the goal is set and subsequently observe whether it has been achieved. Involvement of patients in goal setting can result in more effective achievement and greater satisfaction for those providing healthcare. However, not all patients are able to make decisions for themselves nor to be full partners in setting goals, such as those who are unconscious, confused or mentally handicapped. In these instances relatives or friends may become involved in establishing appropriate goals with nurses.

Planning – once problems are identified those which need immediate attention are addressed. A plan of action is formulated which includes the following key activities:

Planning – once problems are identified those which need immediate attention are addressed. A plan of action is formulated which includes the following key activities:

Implementation – putting the plan into action, which involves the following activities:

Implementation – putting the plan into action, which involves the following activities:

Evaluation – determining how well the plan has worked and whether any changes need to be made.

Evaluation – determining how well the plan has worked and whether any changes need to be made.

Observation of the patient

Are they on a trolley or in a wheelchair?

Are they on a trolley or in a wheelchair?

Are they walking using a stick or do they have a limp or an unsteady gait?

Are they walking using a stick or do they have a limp or an unsteady gait?

Facial colour, pallor, flushed or cyanosed.

Facial colour, pallor, flushed or cyanosed.

Respiratory difficulty, rapid or shallow breathing.

Respiratory difficulty, rapid or shallow breathing.

Cool, moist or dehydrated skin.

Cool, moist or dehydrated skin.

Ischaemia of the eyelids, lips, gums and tongue.

Ischaemia of the eyelids, lips, gums and tongue.

Facial expression indicating pain, anxiety, fear, anger.

Facial expression indicating pain, anxiety, fear, anger.

Oedema of the feet, legs or sacral area.

Oedema of the feet, legs or sacral area.

Increased or decreased body weight; loose-fitting clothing or false teeth.

Increased or decreased body weight; loose-fitting clothing or false teeth.

Interviewing the patient

Assess relevant health history, enquiring if there is any family history, any episodes of fatigue, restlessness, syncope or confusion.

Assess relevant health history, enquiring if there is any family history, any episodes of fatigue, restlessness, syncope or confusion.

Ask patients to show you any medications that they are taking or take occasionally and check that the medications are taken as prescribed. If the patient does not have the medications on hand, ask a relative or friend to bring them in to you.

Ask patients to show you any medications that they are taking or take occasionally and check that the medications are taken as prescribed. If the patient does not have the medications on hand, ask a relative or friend to bring them in to you.

Determine any risk factors for disease, such as diabetes, a high-fat/cholesterol diet, does the patient smoke or take any exercise?

Determine any risk factors for disease, such as diabetes, a high-fat/cholesterol diet, does the patient smoke or take any exercise?

Ask the patient about coping strategies which may help to determine how well the patient copes with stress.

Ask the patient about coping strategies which may help to determine how well the patient copes with stress.

Determine any religious beliefs or preferences, sleeping and eating patterns.

Determine any religious beliefs or preferences, sleeping and eating patterns.

Ask about psychological status, e.g. recent bereavement, eating habits.

Ask about psychological status, e.g. recent bereavement, eating habits.

Determine social status of the patient.

Determine social status of the patient.

Questions about diet, income, family concerns and job status are necessary as all can influence health and recovery.

Questions about diet, income, family concerns and job status are necessary as all can influence health and recovery.

Patient communication

The communication process comprises five elements:

1. The sender or encoder of the message.

3. The receiver or decoder of the message.

4. Feedback that the receiver conveys to the sender.

When planning to meet patients’ communication needs there are six essential areas to include:

1. Orientation to the time, day, date, place, people, environment and procedures.

2. Specific patient teaching on any aspect of care.

3. Adopting methods to overcome patients’ sensory deficits.

4. Comforting patients who are confused or hallucinating.

5. Communications which maintain the patient’s personal identity.

Resources, nursing actions and aids which can be used in connection with these six areas are suggested in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1 Communication aids to meet patient needs (Manley & Bellman 2000)

| Essential areas of | Resource/aid/nursing planning action |

|---|---|

| Orientation to time, place, person, people, environment and procedures | |

| Communication which maintains | |

| Special patient teaching | |

| Overcoming sensory deficits | |

| Comforting patients | |

| Helping communication of |

Barriers to and interference with communication can occur at any point in the process. A summary of potential problems relating to the patient’s reception of messages from the nurse in acute hospital settings is provided in Box 3.1.

Box 3.1 Potential problems relating to communicating in practice

| Environment | |

| Distortion of the message | |

| Distractions | |

| Patient | |

| Psychological | |

| Physical | |

| Social | |

3.2 Assessment

Episodes of fatigue, restlessness, syncope or confusion.

Episodes of fatigue, restlessness, syncope or confusion.

Risk factors, such as diabetes, a high-fat/cholesterol diet, smoking, exercise regime, coping strategies.

Risk factors, such as diabetes, a high-fat/cholesterol diet, smoking, exercise regime, coping strategies.

Religious beliefs or preferences.

Religious beliefs or preferences.

Social status, to determine stress levels, diet, income, family concerns and job status.

Social status, to determine stress levels, diet, income, family concerns and job status.

Autonomic nervous system

The sympathetic nervous system:

Is active in response to stressors.

Is active in response to stressors.

Is responsible for stimulating smooth muscle fibres to contract (i.e. excitation).

Is responsible for stimulating smooth muscle fibres to contract (i.e. excitation).

Stimulates the adrenal medulla to release the hormones adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine).

Stimulates the adrenal medulla to release the hormones adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine).

The parasympathetic nervous system:

Is active in response to stressors.

Is active in response to stressors.

Causes relaxation (i.e. inhibition) and is most active during sleep and rest.

Causes relaxation (i.e. inhibition) and is most active during sleep and rest.

The Glasgow Coma Scale

Record conscious level and the activity of the ANS or mental state.

Record conscious level and the activity of the ANS or mental state.

Assess consciousness and standardize clinical observations of patients with impaired consciousness.

Assess consciousness and standardize clinical observations of patients with impaired consciousness.

Monitor the progress of head-injured patients and those undergoing intracranial surgery.

Monitor the progress of head-injured patients and those undergoing intracranial surgery.

Detect any other neurological disorder (cerebral vascular accident, encephalitis, meningitis).

Detect any other neurological disorder (cerebral vascular accident, encephalitis, meningitis).

Minimize variation and subjectivity in the clinical assessment of patients.

Minimize variation and subjectivity in the clinical assessment of patients.

Provide a neurological assessment that might indicate the level of patient dependency and subsequent need for nursing interventions.

Provide a neurological assessment that might indicate the level of patient dependency and subsequent need for nursing interventions.

It focuses on the evaluation of three parameters: eye opening, motor response and verbal response (Table 3.2). The patient’s best achievement is recorded for each parameter. The scores are then added together to give an overall assessment of the patient’s neurological status. A score of 15 represents the most responsive while a score of 3 is the least responsive.

Table 3.2 The three modes of behaviour used in the GCS (Edwards, 2001)

| Response | Description | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Best eye opening response | Spontaneously: opens eyes spontaneously | 4 |

| To speech: opens to verbal stimuli; not necessarily to command of ‘open your eyes’, a verbal stimulus may be normal, repeated or even loud | 3 | |

| To pain: does not open eyes to previous stimuli, opens eyes to central painful stimuli | 2 | |

| None: does not open eyes to any stimulus | 1 | |

| Best verbal response | Orientated to time, place and person | 5 |

| Disorientated and confused to any of the following: time, place or person; ability to hold a conversation but not accurately answering questions | 4 | |

| Inappropriate words: uses words or phrases making little or no sense, words may be said at random, shouting or swearing | 3 | |

| Incomprehensible sounds: makes unintelligible sounds (moans and groans) | 2 | |

| No response: makes no sounds or speech | 1 | |

| Other: if patient is intubated or has a tracheotomy, document ETT or trach; if dysphasia or aphasic document D or A | ||

| Best motor response | Obeys verbal commands: follows commands, even if weakly | 6 |

| Localizes to painful stimuli: attempts to locate or remove painful stimulus | 5 | |

| Withdraws from painful stimuli: moves away from painful stimulus or may bend or flex arm towards the source of pain but does not actually localize or remove source of pain | 4 | |

| Abnormal flexion and adduction of arms coupled with extensions of legs and plantar flexion of feet (decorticate posturing) | 3 | |

| Abnormal extension, adduction and internal rotation of upper and lower extremities (decerebrate posturing) | 2 | |

| No response, even to painful stimulus | 1 |

Painful stimulus

Peripheral painful stimulation:

Peripheral painful stimulation:

Pupil size and reaction to light

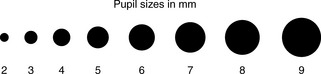

The pupil size (Fig. 3.1) – average pupil size is 2–5 mm.

The pupil size (Fig. 3.1) – average pupil size is 2–5 mm.

The pupil reaction to light: brisk, sluggish or fixed.

The pupil reaction to light: brisk, sluggish or fixed.

The shape of the pupil – should be round.

The shape of the pupil – should be round.

If both pupils react equally to light and are equal in size.

If both pupils react equally to light and are equal in size.

When undertaking the pupillary response the following should be observed:

The light should be shone into the patient’s eyes to see if they constrict.

The light should be shone into the patient’s eyes to see if they constrict.

The light should not be shone directly into the patient’s eyes; a torch should be shone from the side into the eye.

The light should not be shone directly into the patient’s eyes; a torch should be shone from the side into the eye.

It is best to carry this out in dim lighting as one sees the eyes constrict better when light is shone on them. Protocols should exist to eliminate any inconsistencies in the patient’s score (e.g. discrepancies in dimming the light could occur during the night).

It is best to carry this out in dim lighting as one sees the eyes constrict better when light is shone on them. Protocols should exist to eliminate any inconsistencies in the patient’s score (e.g. discrepancies in dimming the light could occur during the night).

Progressive dilatation and loss of pupil reaction on one side occur as a result of pressure on the third cranial nerve on that side, indicating an enlarged intracranial mass (haematoma).

Progressive dilatation and loss of pupil reaction on one side occur as a result of pressure on the third cranial nerve on that side, indicating an enlarged intracranial mass (haematoma).

Progressive cerebral oedema eventually leads to compression of the third cranial nerve on the other side, so neither pupil then reacts to light (severe brain injury).

Progressive cerebral oedema eventually leads to compression of the third cranial nerve on the other side, so neither pupil then reacts to light (severe brain injury).

Some drugs, e.g. atropine, dilate the pupil; opiates, e.g. morphine, constrict the pupil.

Some drugs, e.g. atropine, dilate the pupil; opiates, e.g. morphine, constrict the pupil.

Observation of vital signs

The last section of the GCS is the observation of vital signs:

A high temperature can be due to damage to the hypothalamus, which increases the cerebral metabolic oxygen requirement, an unwanted complication when oxygenation of the brain may already be depleted.

A high temperature can be due to damage to the hypothalamus, which increases the cerebral metabolic oxygen requirement, an unwanted complication when oxygenation of the brain may already be depleted.

Control centres for blood pressure, heart rate and respiration are all located in the brainstem so damage to this area of the brain can lead to:

Control centres for blood pressure, heart rate and respiration are all located in the brainstem so damage to this area of the brain can lead to:

Neurological observations should be recorded at frequent intervals, 1 hour being the maximum time allowed.

Neurological observations should be recorded at frequent intervals, 1 hour being the maximum time allowed.

Stress

1. The alarm reaction – widespread physiological response which includes a large outflow into the bloodstream of adrenal hormones in an attempt to defend the body from the stresssor.

2. Resistance or adaptation – where an attempt is made by the body to re-establish equilibrium and to regain control to maintain homeostasis. If the body is unable to re-establish homeostasis because of persistent exposure to the stressor then the third phase will result.

Hearing the initial diagnosis may be a difficult and stressful process; the fear and anxiety generated by the news may be disruptive and debilitating, making it more difficult for the patient to absorb further information or to make informed choices.

Hearing the initial diagnosis may be a difficult and stressful process; the fear and anxiety generated by the news may be disruptive and debilitating, making it more difficult for the patient to absorb further information or to make informed choices.

Perception of the situation itself is an intricate concept which may in turn be affected by past experiences, genetic predisposition, values and beliefs, self-concept and the level of anxiety at the time the stressor is perceived.

Perception of the situation itself is an intricate concept which may in turn be affected by past experiences, genetic predisposition, values and beliefs, self-concept and the level of anxiety at the time the stressor is perceived.

Some treatments use powerful drugs, accompanied by side-effects which may include nausea and vomiting.

Some treatments use powerful drugs, accompanied by side-effects which may include nausea and vomiting.

Continued exposure to stressors can result in the development of stress ulcers, reduced wound healing and cardiac function and a reduced immune response to infection, amongst other physiological and psychological sequelae.

Continued exposure to stressors can result in the development of stress ulcers, reduced wound healing and cardiac function and a reduced immune response to infection, amongst other physiological and psychological sequelae.

Coping with specific life events – changes which occur through choice (marriage or divorce) or may be totally unforeseen (bereavement, redundancy, accidental injury or long-term illness).

Coping with specific life events – changes which occur through choice (marriage or divorce) or may be totally unforeseen (bereavement, redundancy, accidental injury or long-term illness).

Assessment of recent and current major life events and/or crises, as these may have precipitated the acute illness.

Assessment of recent and current major life events and/or crises, as these may have precipitated the acute illness.

Assessment of the individual’s normal coping mechanisms and support networks, so that these can be enhanced or reinforced.

Assessment of the individual’s normal coping mechanisms and support networks, so that these can be enhanced or reinforced.

Recognition that the present acute illness may cause stress in itself, particularly with regard to:

Recognition that the present acute illness may cause stress in itself, particularly with regard to:

The need to assist the patient’s family members with positive coping mechanisms in a situation that may be perceived as stressful for them.

The need to assist the patient’s family members with positive coping mechanisms in a situation that may be perceived as stressful for them.

Catecholamines – adrenaline increases heart rate, cardiac output, metabolic rate and blood glucose levels and causes dilatation of bronchioles; noradrenaline influences peripheral vasoconstriction, increasing blood pressure.

Catecholamines – adrenaline increases heart rate, cardiac output, metabolic rate and blood glucose levels and causes dilatation of bronchioles; noradrenaline influences peripheral vasoconstriction, increasing blood pressure.

Glucocorticoids – cortisol from the adrenal cortex leads to gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis, proteolysis and lipolysis and enhances adrenaline’s vasoconstrictive effects.

Glucocorticoids – cortisol from the adrenal cortex leads to gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis, proteolysis and lipolysis and enhances adrenaline’s vasoconstrictive effects.

Mineralocorticoids – aldosterone increases sodium reabsorption in the renal tubules, resulting in the reduction of urine output and increase in intravascular volume, providing compensation for stress and fluid/blood loss.

Mineralocorticoids – aldosterone increases sodium reabsorption in the renal tubules, resulting in the reduction of urine output and increase in intravascular volume, providing compensation for stress and fluid/blood loss.

Antidiuretic hormone (ADH) – targets kidney tubules and inhibits or prevents urine formation. Less urine is produced, blood volume increases and the thirst response will be aroused.

Antidiuretic hormone (ADH) – targets kidney tubules and inhibits or prevents urine formation. Less urine is produced, blood volume increases and the thirst response will be aroused.

Pain

The visual analogue scale – a straight line, usually 10 cm in length, with one extreme marked ‘no pain at all’ and the other end marked ‘worst possible pain’. Descriptive words may be added.

The visual analogue scale – a straight line, usually 10 cm in length, with one extreme marked ‘no pain at all’ and the other end marked ‘worst possible pain’. Descriptive words may be added.

Numerical rating scales are marked 0–10, with 0 signifying ‘no pain’ and 10 meaning ‘unbearable pain’.

Numerical rating scales are marked 0–10, with 0 signifying ‘no pain’ and 10 meaning ‘unbearable pain’.

Verbal rating scales or verbal descriptors use 4–5 preset categories and consist of a list of adjectives that describe levels of pain intensity by extremes (‘no pain’, ‘mild pain’, ‘discomfort’, ‘severe/distressing pain’, ‘excruciating/very severe pain’).

Verbal rating scales or verbal descriptors use 4–5 preset categories and consist of a list of adjectives that describe levels of pain intensity by extremes (‘no pain’, ‘mild pain’, ‘discomfort’, ‘severe/distressing pain’, ‘excruciating/very severe pain’).

The Bourbonnais pain assessment tool – two pain assessment tools designed to complement each other, one for the patient and one for the nurse. The tool consists of two parts: a scale ranging from 0 (reflecting no pain) to 10 (reflecting excruciating pain) and a list of adjectives which describe different perceptions of pain. The person experiencing pain is then asked to match the word or words that describe his pain to the number, which corresponds to the intensity of the pain.

The Bourbonnais pain assessment tool – two pain assessment tools designed to complement each other, one for the patient and one for the nurse. The tool consists of two parts: a scale ranging from 0 (reflecting no pain) to 10 (reflecting excruciating pain) and a list of adjectives which describe different perceptions of pain. The person experiencing pain is then asked to match the word or words that describe his pain to the number, which corresponds to the intensity of the pain.

The London pain chart – includes a body outline to record the site of pain, a verbal descriptor scale for intensity and measures to relieve pain.

The London pain chart – includes a body outline to record the site of pain, a verbal descriptor scale for intensity and measures to relieve pain.

Once assessed, it is imperative that the pain is treated, as a failure to relieve pain is morally and ethically unacceptable (see Section 5 for pain relief). Pain can have a detrimental effect on a patient’s condition and can significantly slow recovery. The under-treatment of pain can lead to:

Decreased tidal volumes and alveolar ventilation, leading to decreased oxygen delivery to organs.

Decreased tidal volumes and alveolar ventilation, leading to decreased oxygen delivery to organs.

Avoidance of coughing, resulting in an increase in secretions contributing to atelectasis and chest infections.

Avoidance of coughing, resulting in an increase in secretions contributing to atelectasis and chest infections.

Avoidance of movement, leading to an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Avoidance of movement, leading to an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Increased stress response and sympathetic stimulation, resulting in vasoconstriction and tachycardia, raising blood pressure and increasing the workload of the heart.

Increased stress response and sympathetic stimulation, resulting in vasoconstriction and tachycardia, raising blood pressure and increasing the workload of the heart.

Stress, which interferes with intestinal smooth muscle and leads to an increase in metabolic rate, leading to difficulties in meeting nutritional needs and possible loss of weight.

Stress, which interferes with intestinal smooth muscle and leads to an increase in metabolic rate, leading to difficulties in meeting nutritional needs and possible loss of weight.

Under-management of pain

Healthcare professionals

Poor knowledge of pain management.

Poor knowledge of pain management.

Inappropriate attitudes (cancer pain is inevitable).

Inappropriate attitudes (cancer pain is inevitable).

Poor clinical skills (assessing pain).

Poor clinical skills (assessing pain).

Inappropriate beliefs regarding the management of cancer pain (fears of addiction and tolerance to opiates).

Inappropriate beliefs regarding the management of cancer pain (fears of addiction and tolerance to opiates).

A lack of appreciation of the non-physical manifestations of cancer pain.

A lack of appreciation of the non-physical manifestations of cancer pain.

Individual patient

Low expectations of pain management and a belief that pain is inevitable.

Low expectations of pain management and a belief that pain is inevitable.

Inappropriate beliefs regarding pain management strategies (fear of addiction and tolerance).

Inappropriate beliefs regarding pain management strategies (fear of addiction and tolerance).

Beliefs that side-effects of medication are inevitable (sedation).

Beliefs that side-effects of medication are inevitable (sedation).

Good pain relief can reduce these responses to pain, and lead to a safer and improved recovery.