CHAPTER 3. Getting started

rapport and agendas

• Introduction

• Establishing rapport

• Setting the agenda

• Strategy 1. Multiple behaviors – agenda-setting

• Strategy 2. Single behavior — raise subject

1 What would you like to talk about today? We could talk about smoking, exercise, eating, or drinking, all of which affect your recovery from the heart attack. But what do you think? Perhaps you are more concerned about something else?

2 Would you like to talk about any changes to your health like eating or smoking, or have you come here today with other concerns on your mind?

3 Which of exercise or diet do you feel most ready to talk about?

4 Some people find that changing X [behavior] can improve Y [condition]. What do you think?

5 I am concerned about your chest. I wonder how you feel about your smoking?

6 How does your use of alcohol affect this problem [the presenting complaint]? What have you noticed?

Introduction

Practitioner: Your blood pressure is higher than it was last time.

Patient: Really? I feel OK.

Practitioner: Well it is definitely up. Are you taking the tablets regularly?

Patient: Pretty well.

Practitioner: What about cutting down on the alcohol?

Patient: [Starting to look a bit defensive!] Yes, I’m trying to.

Practitioner: Are you sticking to the diet we gave you?

Patient: Trying to.

Sometimes it is difficult to get started on a discussion about behavior change. Good rapport is essential for an honest discussion and for constructive understanding of patients’ behavior and openness to change. Rapport is sometimes quickly established or re-established, and the agenda is often obvious. In some settings, for example, in primary health care, there may already be an existing relationship between the practitioner and the patient, and this will provide a backdrop to the current consultation. In other settings, such as a first appointment with a dietitian, a relationship will need to be established quickly. Rapport is easy to understand and recognize, although sometimes it is taken for granted, and it can be difficult to repair once damaged.

Along with establishing a general rapport is the need to agree the topic for discussion. This may involve raising the issue with patients and also giving them a chance to raise issues with the practitioner. Where there are several possible topics for discussion and time is limited, a choice will need to be made. How this is done can affect how empowered the patient feels during the rest of the consultation.

Establishing rapport

It is not difficult to get things off to a good start. Experienced healthcare practitioners are often highly skilled at this. The guidelines below are basic but essential for avoiding damage to rapport. The most common cause for this damage is prematurely focusing on the topic that is of most interest to the practitioner, and this challenge will be discussed in the next section of this chapter.

Physical setting

The physical setting for the consultation may either promote or obstruct development of a good rapport. An equal power relationship is essential if the consultation is to be conducted in the right spirit. Consider the following factors that may affect this:

• Is the patient’s first encounter in the clinic one in which he or she will be listened to, even if just for a few minutes? Or are they obliged to undergo routine testing which is primarily of concern to the practitioner?

• Do they feel safe to talk? Is there appropriate privacy for patients (sound muffling as well as visual screening)? In some settings, such as pharmacist consultations at a drugstore, much physical work has been done to create environments conducive to health promotion work.

• Can the patient see the computer screen when entries are made in the notes?

• Do the wall posters create an appropriate ambience?

• Does the practitioner’s style of dress unnecessarily suggest a power imbalance?

• Are patients unnecessarily in a vulnerable physical position that may lead to their feeling disempowered; for example, lying back in the dentist’s chair wearing a bib?

• Has everyone in the room (e.g. students) been introduced?

Thoughts and feelings about the consultation

Patients’ expectations will affect rapport. They will expect or hope to be handled by the practitioner in a certain way. These can be checked and any misunderstandings clarified. Patients may also have come with immediate problems or concerns that will need addressing before they will be able to focus on other matters like behavior change. It is important to identify these and respond appropriately.

It is also worth acknowledging the context of the consultation for patients, and their feelings about this, for example: I’m sorry you’ve been kept waiting at the end of the day. I expect you’re impatient to get home. or It must have been a worrying time for you since your heart attack [diabetes diagnosis, etc.] and I know you’ve already seen several other members of the team to discuss ways to keep you healthy in the future.

It may be necessary to switch focus from treating the patient to guiding them to consider behavior change. After giving an injection, doing a dressing, scaling and polishing teeth, or some other procedure where the patient has (appropriately) been a more or less passive recipient of your ministrations, there will need to be a clear change in focus: Now that’s out of the way, let’s sit down and think together about some of the other things affecting your…

Some situations offer particular challenges. When someone has been very ill and has adjusted to being a compliant and passive patient, for example, after a heart attack, the move into a rehabilitation phase – Let’s look at what you can be doing to help yourself get better – can feel like a real shift. In some healthcare settings, patients have had a lot of their autonomy stripped away and have had to learn to be obedient. A secure psychiatric unit might be an example of this. Setting the scene for them to take some control over their health might be particularly challenging in such a context. If the patient feels respected and cared for from the beginning, any subsequent discussion will be easier.

One strategy: a typical day

One useful strategy for establishing rapport is the Typical Day strategy, which is described in detail in Chapter 6 where its benefit to information exchange is highlighted. Here the patient describes a typical day, and explains how the behavior under discussion fits into this context. The practitioner’s role is to practice restraint and develop an interest in the layers of personal detail provided. It is also useful close to the beginning of a consultation, even if the subject of behavior change has not been raised. If one has time to spare, say 6–8 minutes, it can be a most worthwhile experience for both parties. One can follow the account of a typical day in general without reference to any behavior, or can relate the account to a particular behavior: Tell me what you might eat in a typical day. If carried out skillfully, rapport will be strengthened immeasurably.

Setting the agenda

Jennifer, 35 years old and asthmatic, finds it very difficult to remember to take her medication regularly, smokes 20 cigarettes a day, lives in a family where all the adults smoke indoors and is very inactive. She says that after being on her feet all night, the last thing she wants to do in her spare time is exercise!

Sometimes there are so many things contributing to a person’s poor health that it is difficult to know where to begin.

Of all the judgments made in a behavior change, the poorest often arise from a premature leap into specific discussion of a change when the patient is more concerned about something else. Indeed, this kind of premature leap can become almost institutionalized in a treatment setting, where patients are encouraged to change their behavior before they are ready to do so.

Sometimes it can be a relatively mundane matter that prevents a focus on behavior change; a patient who arrives at a consultation upset about a minor car accident might not be able to concentrate well on anything the practitioner says. Sometimes it is a personal matter that the patient is more concerned with, and might want to talk about; someone who has recently had a heart attack might be pre-occupied with matters of life and death. To talk about getting more exercise under these circumstances could be poorly timed, even insensitive. A critical early task therefore is to agree on the agenda.

Even when behavior change is a viable topic for discussion, one is often faced with multiple, interrelated health behaviors. For example, many excessive drinkers also smoke, and many who eat a fatty diet do little exercise. Thus, several health behaviors deemed to be risky often co-exist in individuals. Sufferers from diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic conditions frequently face the challenge of more than one change. Deciding what to talk about first is thus a crucial initial step.

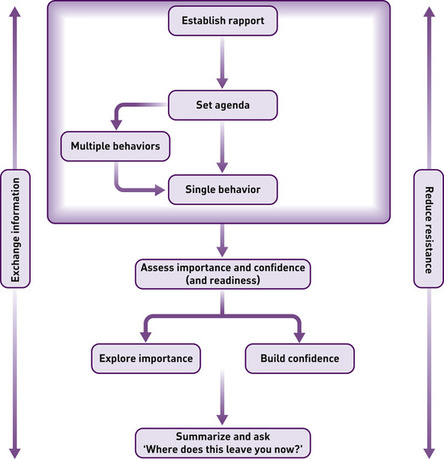

We have made a distinction in this chapter between single and multiple behavior change discussions when setting an agenda. We advise practitioners to make a clear and conscious choice between using either Strategy 1 (for multiple behaviors) or Strategy 2 (for a single behavior). This is because we have noticed so many practitioners who, when faced with a range of possible changes, prematurely oblige a patient to discuss one particular behavior at the expense of others. If someone is more ready to change their pattern of exercise than their diet, why focus on diet? At this stage of the consultation, our assumption is that the patient should be given control of its direction.

Strategy 1. Multiple behaviors — agenda-setting

Negotiating change is a specific process. It is applicable to a range of behaviors but can only be used with regard to one specific behavior at a time. It is not possible to effectively negotiate a ‘healthier lifestyle in general’. We are all at different stages of readiness to change over different issues. Even within one topic such as diet, we may be ready to make one change (e.g. snack on fruit instead of chocolate) but not ready to make another (e.g. eat cereal or oatmeal/porridge for breakfast instead of bacon). Sometimes changing one behavior will have a positive effect on another, but it is important to keep the consultation process to one topic at a time. When there is a range of behaviors that could be discussed, it is essential to prioritize and focus upon one clear objective. This makes the whole process more manageable. How do you decide what to talk about?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access