Chapter 3 Cardiac conditions

INTRODUCTION

Although cardiac disease in pregnancy complicates few pregnancies, it continues to contribute significantly to maternal and fetal mortality and morbidity. Some 10–25% of all maternal deaths are due to cardiac disease (Avila et al 2003). The main causes of maternal mortality are: pulmonary hypertension, endocarditis, cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, coronary artery disease and sudden lethal cardiac arrhythmia. Medical advances have increased the number of women who survive to adulthood and successfully achieve pregnancy. The midwife must therefore have a good understanding of these disorders in order to care for them appropriately.

RELEVANT ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

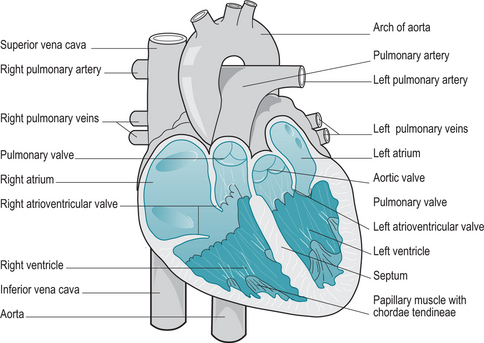

The heart is a cone-shaped muscular hollow organ situated in a space between the lungs – the mediastinum (Fig. 3.1). The muscular wall is composed of an outer protective layer, the pericardium, a middle muscular layer, the myocardium and an innermost layer – the endocardium. The pericardium is a double outermost layer which surrounds the heart preventing overfilling and also allowing free movement within the mediastinum. The muscular myocardium varies in thickness reflecting the work required by the underlying chamber of the heart. The endothelial endocardium lines the heart, the valves and the blood vessels leaving the heart and provides a smooth surface reducing friction between blood and the walls of the heart.

The four valves of the heart are:

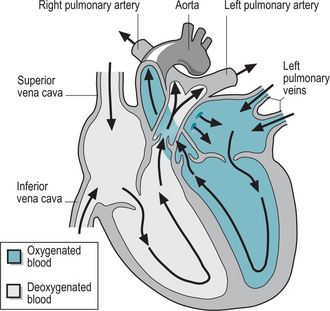

Deoxygenated blood from the body enters the right atrium of the heart via the vena cava (Fig. 3.2). Once the atrium is filled, the tricuspid valve opens and, assisted by contraction of the atria, the blood is moved into the right ventricle. Once this has filled, the ventricle contracts and pushes the blood into the pulmonary arteries. Blood is carried to the lungs where it is oxygenated and then returned to the left side of the heart. In synchrony with the right side, oxygenated blood pours into the left atrium, is moved into the left ventricle and then into the aorta, the largest artery in the body. The heart then rests for a brief moment of time. The entire cycle – the cardiac cycle – takes 0.8 s and is controlled by the pacemaker of the heart.

PHYSIOLOGICAL CHANGES IN PREGNANCY

Prenatally cardiac output increases from the first trimester until it reaches a plateau at 28–34 weeks. This is due to the increase in blood volume, the effects of the hormones of pregnancy and the increase in vasculature through the uterus. These alterations increase the workload of the heart considerably but healthy women are able to adjust to these physiological changes with ease (see alsoCh. 2). However, the changes provoke symptoms similar to mild cardiac disease such as dyspnoea, especially with exercise, fatigue and oedema. Additionally, the above changes may provoke the occasional dysrhythmia or episode of palpitations (Jordan 2002). There is also an increased risk of thromboembolism during pregnancy with the risk being highest after birth (Lee 2005).

CARDIAC DISEASE IN PREGNANCY

The presence of heart disease although rare, is associated with a significant risk to mother and fetus. In the most recent Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH) 2000–2002, cardiac disease was the leading cause of indirect death with 44 mortalities in the 3 years (Lewis & Drife 2004). Cardiac disease was the second most common cause of maternal death overall, second only to psychiatric causes and more frequent than thromboembolic disease. In women with congenital heart disease, the presence of pulmonary hypertension was the crucial factor. In acquired disorders, the main causes were cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction, aneurysm and dissection of the aorta. Eisenmenger’s syndrome, although rare, is a life-threatening condition in pregnancy, carrying a 40% mortality rate with each pregnancy

Cardiac disorders are classified as congenital or acquired. In women of childbearing age, acquired disorders are rare. The most common cause of an acquired cardiac disorder in fertile women is rheumatic heart disease as a complication of rheumatic fever as a child. Congenital heart disease is more common in the UK (Iserin 2001) and occurs in 0.5–2% of the population (Gilbert & Harmon 1998).

Pathophysiology of cardiac disease

Rheumatic heart disease

In those individuals with rheumatic heart disease, the endocardium becomes inflamed and subsequently scarred. This is found most commonly on the valves of the heart, particularly the mitral valve and to a lesser extent, the tricuspid valve. The valves become distorted and dysfunctional. The ends of the cusps of the valves become roughened, fuse together and the opening narrowed, a condition known asmitral or atrial (relating to the tricuspid valve) stenosis. Further, the damage may prevent the cusps of the valves from closing fully allowing backflow of blood in the heart, mitral/atrial incompetence. The result of these changes is a damaged heart in which circulation of blood is impaired (Box 3.1). The heart has to work harder to pump sufficient blood around the body. Over time, the heart increases in size, a condition known as hypertrophy. This weakens the heart and any further strain, such as pregnancy, may lead to heart failure.

Other conditions that have a similar effect are:

Ischaemic heart disease and myocardial infarction

With increasing dietary and obesity problems in the industrialized world, it is becoming increasingly common to meet women who have the early signs of ischaemic heart disease. Blood vessels are damaged by a high level of circulating fats and plaques of atherosclerosis (Box 3.2) begin to narrow the lumen of the blood vessels (Foxton 2003). Where this happens in the coronary arteries surrounding and nourishing the tissues of the heart, the heart becomes ischaemic and is unable to continue functioning properly. Women are increasingly leaving pregnancy until they are olderwith the added risk that ischaemic heart disease may be well advanced. The added workload to the heart, of pregnancy and childbirth, may result in angina or rarely a heart attack – myocardial infarction (MI). Acute myocardial infarction during childbirth is very rare, occurring in1 in 10 000–30 000 women (Baird & Kennedy 2006). However, maternal mortality from an MI may be up to 40%. Permanent changes to the heart due to chronic hypertension may also complicate pregnancy.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree