Drugs Used to Treat Thromboembolic Disorders

Objectives

1 Explain the primary purposes of anticoagulant therapy.

2 Identify the effects of anticoagulant therapy on existing blood clots.

3 Describe conditions that place an individual at risk for developing blood clots.

4 Identify specific nursing interventions that can prevent clot formation.

5 Explain laboratory data used to establish dosing of anticoagulant medications.

6 Describe specific monitoring procedures to detect hemorrhage in the patient taking anticoagulants.

Key Terms

thromboembolic diseases ( ) (p. 424)

) (p. 424)

thrombosis ( ) (p. 424)

) (p. 424)

thrombus ( ) (p. 424)

) (p. 424)

embolus ( ) (p. 424)

) (p. 424)

intrinsic clotting pathway ( ) (p. 424)

) (p. 424)

extrinsic clotting pathway ( ) (p. 424)

) (p. 424)

platelet inhibitors ( ) (p. 426)

) (p. 426)

anticoagulants ( ) (p. 426)

) (p. 426)

thrombin inhibitors (p. 426)

thrombolytic agents ( ) (p. 426)

) (p. 426)

Thromboembolic Diseases

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

Diseases associated with abnormal clotting within blood vessels are known as thromboembolic diseases and are major causes of morbidity and mortality. Thrombosis is the process of formation of a fibrin blood clot (thrombus). An embolus is a small fragment of a thrombus that breaks off and circulates until it becomes trapped in a capillary, causing ischemia or infarction to the area distal to the obstruction (e.g., cerebral embolism, pulmonary embolism).

Major causes of thrombus formation are immobilization with venous stasis; surgery and the postoperative period; trauma to lower limbs; certain illnesses (e.g., heart failure, vasospasm, ulcerative colitis); cancers of the lung, prostate, stomach, and pancreas; pregnancy and oral contraceptives; and heredity.

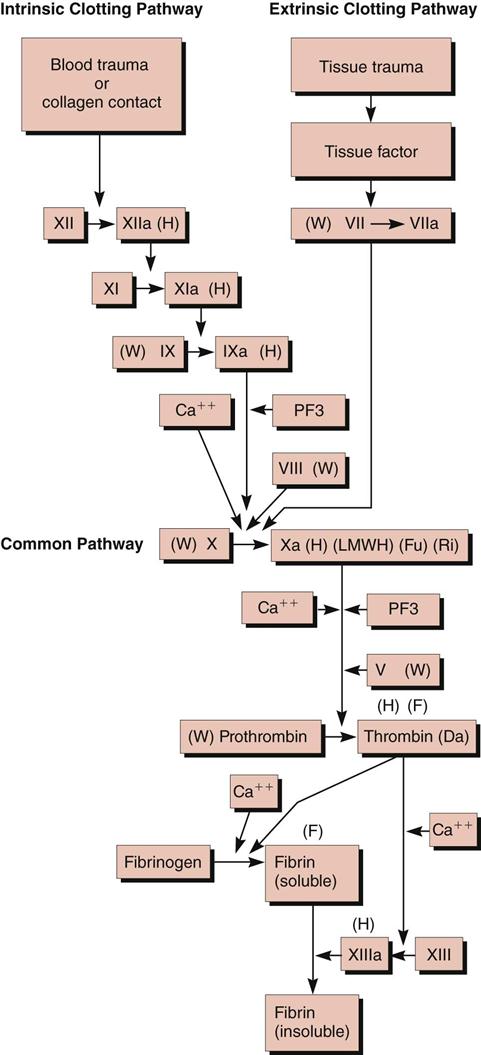

Normally, blood clot formation and dissolution constitute a fine balance within the cardiovascular system. The clotting proteins normally circulate in an inactive state and must be activated to form a fibrin clot. When there is a trigger, such as increased blood viscosity from bed rest and stasis or damage to a blood vessel wall, the clotting cascade is activated. For example, if a blood vessel is injured and collagen in the vessel wall is exposed, platelets first adhere to the site of injury and release adenosine diphosphate (ADP), leading to additional platelet aggregation that forms a “platelet plug.” At the same time platelets are forming a plug, the intrinsic clotting pathway is triggered by the presence of collagen activating factor XII. Activated factor XIIa activates factor XI to XIa, which activates factor IX to IXa. Factor IXa, in the presence of calcium, platelet factor 3 (PF3), and factor VIII, activates factor X. Activated factor Xa, in the presence of calcium, PF3, and factor V, stimulates the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin (Figure 27-1).

Sources outside the blood vessels, such as tissue extract or thromboplastin (tissue factor), can trigger the extrinsic clotting pathway by activating factor VII to VIIa. Factor VIIa can also activate factor X, which results in the formation of thrombin. After stimulation from the intrinsic or extrinsic pathway, thrombin, in the presence of calcium, activates fibrinogen to soluble fibrin. With time and the presence of factor XIII, the loose fibrin mesh is converted to a tight, insoluble fibrin mesh clot. Thrombin also stimulates platelet aggregation and stimulates further activity of factors V, VIIa, VII, and Xa. As the fibrin clot is being formed, it also triggers the release of fibrinolysin, an enzyme that dissolves fibrin, preventing the clot from spreading.

Historically, thrombi have been classified into red and white blood clots. A red thrombus is actually a venous thrombus and is composed almost entirely of fibrin and erythrocytes (red blood cells), with a few platelets. Venous thrombi generally form in response to venous stasis after immobility or surgery. The poor circulation prevents dilution of activated coagulation factors by rapidly circulating blood. The most common cause of red thrombus formation is deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremities. These thrombi may extend upward into the veins of the thigh and have the potential of fragmenting, subsequently causing life-threatening pulmonary emboli. White thrombi develop in arteries and are composed of platelets and fibrin. This type of thrombus forms in areas of high blood flow in response to injured vessel walls. Coronary artery occlusion leading to myocardial infarction is an example of a white thrombus.

Treatment of Thromboembolic Diseases

Diseases caused by intravascular clotting (e.g., deep vein thrombosis, myocardial infarction, dysrhythmias with clot formation, coronary vasospasm leading to thrombus formation) are major causes of death. When thrombosis is suspected, patients are admitted to the hospital, where they can be closely observed for further signs and symptoms of thrombosis formation and progression, and anticoagulant and thrombolytic therapy can be started. A combination of physical examination, patient history, Doppler ultrasound, phlebography, radiolabeled fibrinogen studies, and angiography is used to diagnose the presence and cause of a thrombus and embolism. Routine laboratory tests that are run to assess the clotting process and ensure that occult bleeding is not present are platelet count, hematocrit, prothrombin time (PT) reported as the international normalized ratio (INR), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), activated clotting time (ACT), urinalysis, and stool guaiac test.

Nonpharmacologic prevention and treatment of thromboembolic disease include patient education on how to prevent venous stasis (e.g., leg exercises, leg elevation) and clinical use of sequential compression devices (SCDs). If a patient having a heart attack (myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome) can be transported to a cardiac intensive care facility soon after symptoms develop, revascularization treatment to reopen the coronary arteries may be performed. Thrombolytic agents may be used to dissolve the clot before it is permanently attached to vessel walls causing complete obstruction. Revascularization procedures used may be a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG). In PCI, also known as angioplasty, a catheter is inserted into the femoral artery and advanced up the aorta into the site of the coronary artery obstruction. The tip of the catheter can be equipped with different types of devices, such as a balloon to dilate the artery obstruction, or blades or lasers to reduce or remove the obstruction. A vascular stent is then often placed in the artery to keep the formerly obstructed area open. If a patient has multiple narrowed or obstructed arteries, a CABG procedure is performed, wherein a segment of the saphenous vein from the leg is harvested and attached to the coronary artery above and below the obstruction, forming a bypass for perfusion to the myocardial tissues below. The internal mammary artery can also be used in this procedure. The major pharmacologic treatments used in the prevention and treatment of thromboembolic diseases are platelet inhibitors, anticoagulants, thrombin inhibitors, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, and thrombolytic agents.

Drug Therapy for Thromboembolic Diseases

Actions

The pharmacologic agents used to treat thromboembolic disease act either to prevent platelet aggregation or inhibit a variety of steps in the fibrin clot formation cascade (see Figure 27-1). See individual drug monographs for a more detailed discussion of mechanisms of action.

Uses

Agents used in the prevention and treatment of thromboembolic disease can be divided into platelet inhibitors, anticoagulants, thrombin inhibitors, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, and thrombolytic agents. Antiplatelet agents (e.g., aspirin, clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor) are used preventively to reduce arterial clot formation (white thrombi) by inhibiting platelet aggregation. Anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin, fondaparinux, rivaroxaban, heparin, heparin derivatives [enoxaparin, dalteparin]) are also used prophylactically to prevent the formation of arterial and venous thrombi in predisposed patients. The heparin derivatives are also known as low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs). The primary purpose of anticoagulants is to prevent the formation of new clots or the extension of existing clots. They cannot dissolve an existing clot. Dabigatran, an oral direct thrombin inhibitor, is used to prevent strokes and systemic emboli in patients with atrial fibrillation. The glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors are used to prevent clot formation during PCI procedures. Thrombolytic agents (e.g., streptokinase, alteplase) are used to dissolve thromboemboli once formed.

Laboratory Tests for Monitoring Anticoagulant Therapy

While receiving anticoagulant therapy, the patient will undergo regular monitoring of coagulation studies, including monitoring of the PT reported as the INR, ecarin clotting time (ECT), thrombin time (TT), aPTT, and platelet counts. These laboratory studies monitor the time it takes for the blood to clot. Results of these studies may be used as guidelines for drug dosing by the prescriber.

Nursing Implications for Anticoagulant Therapy

Nursing Implications for Anticoagulant Therapy

Assessment

History.

Ask specific questions to determine whether the patient or family members have a history of any type of vascular difficulty. Patients at greater risk for clot formation are those with a history of clot formation; those who have recently undergone abdominal, thoracic, or orthopedic surgery; and those on prolonged bed rest or anticoagulant therapy. Does the patient have any disease processes that could potentially increase the risk of bleeding (e.g., ulcer disease, concurrent chemotherapy or radiation therapy)?

Current Symptoms

Medications

Basic Assessment

Diagnostic Studies.

Review completed diagnostic studies and laboratory data (e.g., PT, aPTT, INR), hematocrit, platelet count, Doppler studies, exercise testing, serum triglyceride levels, arteriogram, cardiac enzyme studies.

Implementation

Techniques for Preventing Clot Formation

Patient Assessment.

Monitor vital signs and mental status every 4 to 8 hours or more frequently, depending on the patient’s status. Observe for signs and symptoms of bleeding caused by medications (e.g., blurred vision, hematuria, ecchymosis, occult blood in the stools, change in mentation).

Nutritional Status

Laboratory and Diagnostic Data.

Monitoring and reporting laboratory results to the prescriber are essential during anticoagulant therapy. Coagulation tests that might be ordered include the following: whole blood clotting time (WBCT), ECT, TT, PT, aPTT, and ACT. The PT, reported as INR, is routinely used to monitor warfarin therapy, and the aPTT is most commonly used to monitor heparin therapy. The ECT and TT are used to monitor dabigatran therapy.

Medication Administration.

Never administer an anticoagulant without first checking the chart for the most recent laboratory results. Be certain that the anticoagulant to be administered is ordered after the most recent results have been reported to the health care provider. Follow policy statements regarding checking of anticoagulant doses with other qualified professionals. Reduce localized bleeding at the injection site by using the smallest needle possible for injections and rotate injection sites. See individual drug monographs for specific administration techniques related to a particular medicine.

Patient Education and Health Promotion

Patient Education and Health Promotion

Nutritional Status

Exercise and Activity

Medication Regimen

Fostering Health Maintenance

Written Record.

Enlist the patient’s aid in developing and maintaining a written record of monitoring parameters (see the Patient Self-Assessment Form for Anticoagulants on the Evolve Web site![]() ). Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient understands how to use the form and instruct the patient to bring the completed form to follow-up visits. During follow-up visits, focus on issues that will foster adherence with the therapeutic interventions prescribed.

). Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient understands how to use the form and instruct the patient to bring the completed form to follow-up visits. During follow-up visits, focus on issues that will foster adherence with the therapeutic interventions prescribed.

Drug Class: Platelet Inhibitors

Actions

Aspirin is well known as a salicylate and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). A unique property of aspirin, when compared with other salicylates, is platelet aggregation inhibition with prolongation of bleeding time. The platelet loses its ability to aggregate and form clots for the duration of its lifetime (7 to 10 days). The mechanism of action is acetylation of the cyclooxygenase enzyme, which inhibits the synthesis of thromboxane A2, a potent vasoconstrictor and inducer of platelet aggregation.

Uses

There is controversy in the literature as to whether aspirin is equally effective for men and women. When used as primary prevention, aspirin therapy was associated with a significant reduction in myocardial infarction among men but had no effect on the incidence of stroke. Conversely, women taking aspirin had a lower rate of stroke, but no effect was found in relation to myocardial infarction. Nevertheless, aspirin is administered to both men and women at the onset of an acute myocardial infarction.

Therapeutic Outcomes

The primary therapeutic outcomes expected from aspirin therapy when used for antiplatelet therapy are reduced frequency of transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), stroke, or myocardial infarction.

Nursing Implications for Aspirin Therapy

Nursing Implications for Aspirin Therapy

Premedication Assessment

Availability

See Tables 20-3 and 20-4.

Dosage and Administration

See Chapter 20.

Prevention of Transient Ischemic Attacks and Stroke.

Adult: PO: 50 to 325 mg daily.

Treatment of Suspected Myocardial Infarction.

Adult: PO: 160 to 325 mg as soon as possible. Continue 160 to 325 mg daily for at least 30 days.

Prevention of Myocardial Infarction.

Adult: PO: 75 to 162 mg daily. Current literature mostly supports the use of 81 mg daily for prevention.

Actions

Dipyridamole is a platelet adhesiveness inhibitor that is thought to work by inhibiting thromboxane A2, increasing cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) in platelets, potentiating prostacyclin-mediated inhibition, and possibly reducing red blood cell uptake of adenosine, which also inhibits platelets.

Uses

Dipyridamole has been used extensively in combination with warfarin to prevent thromboembolism after cardiac valve replacement. It has also been prescribed in combination with aspirin to prevent myocardial infarction, TIAs, and stroke. Recent studies, however, have indicated that the combination is no more effective than aspirin alone.

Therapeutic Outcome

The primary therapeutic outcome from dipyridamole therapy is preventing blood clots secondary to artificial valve placement.

Nursing Implications for Dipyridamole

Nursing Implications for Dipyridamole

Premedication Assessment

Obtain baseline vital signs.

Availability

PO: 25-, 50-, and 75-mg tablets.

Dosage and Administration

Adult: PO: 75 to 100 mg, four times daily with warfarin, to prevent thromboembolism secondary to valve replacement.

Monitoring

Common Adverse Effects.

These symptoms are transient and disappear with continued therapy. Encourage the patient not to discontinue therapy.

Gastrointestinal

Abdominal Discomfort.

Encourage the patient not to discontinue therapy.

Cardiovascular

Hypotension.

Monitor the blood pressure daily in both the supine and standing positions. Anticipate the development of postural hypotension and take measures to prevent an occurrence. Teach the patient to rise slowly from a supine or sitting position, and encourage the patient to sit or lie down if feeling faint.

Drug Interactions

No clinically significant drug interactions have been reported with dipyridamole.

Actions

Clopidogrel is a second-generation thienopyridine chemically related to ticlopidine and prasugrel. Clopidogrel is a prodrug; one of its metabolites, as yet unknown, is thought to act by inhibiting the ADP pathway required for platelet aggregation. The full antiplatelet activity is seen after 3 to 7 days of continuous therapy. The anti-aggregatory effect persists for approximately 5 days after discontinuation of therapy. Clopidogrel also prolongs bleeding time.

Uses

Clopidogrel is used to reduce the risk of additional atherosclerotic events (e.g., myocardial infarction, stroke, vascular death) in patients who have had a recent stroke, recent myocardial infarction, or established peripheral arterial disease. The medical histories of patients at greatest risk include TIAs, atrial fibrillation, angina pectoris, and carotid artery stenosis. Because clopidogrel has a different mechanism of action from aspirin, it is anticipated that health care providers may use both drugs concurrently. The overall safety profile of clopidogrel appears to be at least as good as that of medium-dose aspirin and better than 250 mg of ticlopidine twice daily.

Therapeutic Outcomes

The primary therapeutic outcomes expected from clopidogrel therapy are reduced frequency of TIAs, stroke, myocardial infarctions, or complications from peripheral vascular disease.

Nursing Implications for Clopidogrel

Nursing Implications for Clopidogrel

Premedication Assessment

Availability

PO: 75- and 300-mg tablets.

Dosage and Administration

Adult: PO: Initial dose: 300 mg for acute myocardial infarction and PCI, otherwise, 75 mg. Maintenance: 75 mg once daily with food or on an empty stomach.

Monitoring

Common Adverse Effects

Gastrointestinal

Nausea, Vomiting, Anorexia, Diarrhea.

These effects tend to occur most frequently with early dosages and tend to resolve with continued therapy over the next 2 weeks. They can also be minimized by taking the medication with food. Encourage the patient not to discontinue therapy without first consulting a health care provider.

Serious Adverse Effects

Hematologic

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP).

TTP is a very rare but potentially life-threatening condition that may occur within 2 weeks of the initiation of therapy. Early indications are abnormal neurologic findings and fever, followed by renal impairment. If suspected, contact the prescriber immediately.

Neutropenia, Agranulocytosis.

Neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count below 1200 neutrophils/mm3) was discovered in 0.4% of patients in clinical trials. While neutropenic, patients are very susceptible to infection. Encourage the patient to report symptoms of infection (e.g., sore throat, fever, excessive fatigue) to the physician as soon as possible.

Bleeding.

A normal physiologic effect of clopidogrel is prolongation of bleeding time. Patients should report any incidents of bleeding as soon as possible. Incidents to be reported include nosebleeds, easy bruising, bright red or coffee-ground emesis, hematuria, and dark tarry stools.

Patients should inform other health care practitioners (e.g., other physicians, dentist) that they are receiving platelet inhibitor therapy.

Drug Interactions

Drugs That Increase Therapeutic and Toxic Effects.

Heparin, LMWHs, warfarin, aspirin, NSAIDs, fondaparinux, and direct thrombin inhibitors (e.g., lepirudin, argatroban) will have an additive bleeding effect on the patient. Monitor very closely for indications of bleeding. Caution should be used when any of these drugs are coadministered with clopidogrel.

Actions

Prasugrel is a third-generation thienopyridine that is similar to clopidogrel and ticlopidine. Prasugrel is a prodrug that must be metabolized to the active drug, which then irreversibly binds to the platelet P2Y12 receptors, inhibiting the ADP pathway required for platelet aggregation. The antiplatelet activity is seen after 1 to 2 hours and continues for 24 hours. The anti-aggregatory effect persists for 5 to 9 days after discontinuation of therapy with new platelet production. Prasugrel also prolongs bleeding time. The steady-state effect is seen after 3 days of continuous therapy.

Uses

When compared with clopidogrel, prasugrel shows a greater platelet inhibitory effect and has a more rapid onset of action, but it also has an increased risk of major bleeding. Prasugrel is approved for use in the prevention of blood clot formation in patients suffering a myocardial infarction who are undergoing a PCI with or without stent placement. Prasugrel may be more effective in patients older than 75 years and who have diabetes or a prior myocardial infarction. Clopidogrel remains the first-line thienopyridine in treatment of patients with a myocardial infarction who have a history of TIA or stroke, in those patients being treated with CABG and in those patients over 75 years (with the exception of those over 75 years with diabetes or prior myocardial infarction). Aspirin therapy should be continued with prasugrel therapy.

Therapeutic Outcome

The primary therapeutic outcome expected from prasugrel is reduced blood clot formation in the treatment of a myocardial infarction being treated with a PCI procedure.

Nursing Implications for Prasugrel

Nursing Implications for Prasugrel

Premedication Assessment

Availability

PO: 5- and 10-mg tablets.

Dosage and Administration

Adult: PO: Initially, 60-mg loading dose followed by a daily maintenance dose of 10 mg. If the patient weighs less than 60 kg, 5 mg daily is recommended. Patients should also continue to take aspirin, 75 to 325 mg once daily.

Monitoring

Common Adverse Effects

Hematologic

Bleeding.

The normal physiologic effect of prasugrel is prolongation of bleeding time. Patients should report any incidents of bleeding as soon as possible. Incidents to be reported include nosebleeds, easy bruising, bright red or coffee-ground emesis, hematuria, and dark tarry stools.

Patients should inform other health care practitioners (e.g., another physician, dentist) that they are receiving platelet inhibitor therapy.

Serious Adverse Effects

Hematologic

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP).

TTP is a very rare but potentially life-threatening condition that may occur within the first 3 months of the initiation of therapy. Early indications are abnormal neurologic findings and fever, followed by renal impairment. If suspected, contact the prescriber immediately.

Drug Interactions

Drugs That Increase Therapeutic and Toxic Effects.

Heparin, LMWHs, warfarin, aspirin, NSAIDs, fondaparinux, and direct thrombin inhibitors (e.g., lepirudin, argatroban) will have an additive bleeding effect in the patient. Monitor very closely for indications of bleeding. Caution should be used when any of these drugs are coadministered with prasugrel.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

)

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

)