CHAPTER 27. Asphyxia

Kent Stewart

Asphyxia is a broad term used to describe conditions of inadequate cellular oxygenation. It can be caused by lack of oxygen in the blood, a failure of cells to use oxygen, or the failure of the body to eliminate carbon dioxide (Dolinak, Matshes, & Lew, 2005). Death investigators must recognize that asphyxia is used to describe many conditions in which there is a decrease in the concentration of oxygen in the body accompanied by an increase in the concentration of carbon dioxide. Lack of oxygen, either partial (hypoxia) or total (anoxia), can lead to unconsciousness and death. Asphyxia can occur rapidly or gradually, but death investigators often encounter victims in which this event is sudden in onset and precipitated by trauma or an act of violence.

Suffocation is an often misused word that actually means asphyxia caused by failure of oxygen to reach the blood. It is used to describe cases of entrapment, gaseous inhalations, smothering, and choking as well as mechanical and traumatic asphyxia. Because it is such a broad term, forensic personnel are urged to use precise terms to describe asphyxial phenomena when writing reports or explaining a scenario to jurors, attorneys, and judges.

Asphyxia can be categorized in physiological terms such as anoxic, hypoxic, anemic, stagnant, and histotoxic. However, this type of classification is typically not used in the courtroom because it would be difficult to explain to laypersons. Consequently, death investigators typically explain asphyxia in terms of its underlying causes. This approach facilitates explanations when several interacting causes have combined to cause injury or death.

Before pursuing the various causes of asphyxia, it is important to recall the distinction between the cause and manner of death. The cause of death is defined as the injury, disease, or combination of the two, responsible for initiating the sequence of disturbances, brief or prolonged, that produced the fatal termination. The manner of death is the fashion or circumstances in which the cause of death arose. There are five options in the United States: natural, accident, homicide, suicide, and undetermined. Other countries list additional manners of death such as open verdict, misadventure, and unclassified.

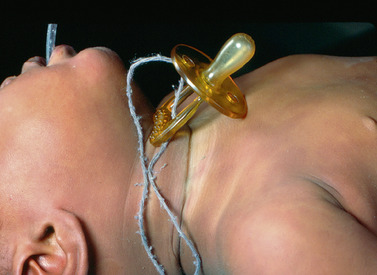

The most common and relatively consistent finding in asphyxial death is the presence of pinpoint bleeding sites, which are called petechiae (Fig. 27-1). Equally important to remember, this finding may be absent in asphyxial deaths (Ely & Hirsch, 2000). Petechiae can occur in many types of deaths including anyone who is found in the prone position, especially those who have died from coagulopathy or cardiovascular disease. They have also been noted in some burn victims (Dolinak, et al., 2005). Petechiae tend to be prominent in most asphyxial deaths and can be seen in the sclera, eyelids, cheeks, and the forehead, as well as other parts of the body. Other characteristic findings of asphyxial deaths include visceral congestion, cyanosis, and fluidity of blood.

Hanging

In hanging, asphyxia is caused by compression or constriction of the structures of the neck by the weight of the body. Hanging can be caused by complete or incomplete suspension of the body. It is not uncommon to come across hangings where the body is in a sitting position or where the feet, toes, or knees are in contact with the ground. The only requirement is that sufficient sustained pressure is applied to the neck. Death is caused by occlusion of the jugular veins and carotid arteries causing insufficient oxygen supply to the brain. Less commonly, obstruction of the airway can occur by obstruction of the trachea or when the ligature causes displacement of the tongue, obstructing air entry.

Examination of the scene of death is important. The best examination occurs if the body is still suspended; however, commonly the body is cut down before the arrival of police and the death investigator. Ideally, the body should be photographed in situ before any disturbance. The body should then be secured (lowered) where additional close-up photographs can be taken. The ligature should always remain in place until the autopsy. If for some reason the ligature has been removed or cut, or if there is a need to remove the ligature, this should be done carefully. If the ligature has been cut, the examiner should tie a string between the ends of the ligature illustrating the original configuration.

The posture, position, and method of hanging and the ligature used must all be examined. Injuries, other than those associated with hanging, require careful assessment and interpretation. Ligatures are most commonly towels, ropes, electrical cords, bed sheets, chains, or clothing (Fig. 27-2). Most hangings are suicidal or accidental, whereas homicidal hangings are rare. Accidental hangings more commonly involve children caught in drawstrings of clothing or exposed curtain drawstrings. In one case investigated by the author, a child was found hanging from the drawstring of a blind that hung into the crib.

As weight is applied, there is upward movement of the noose or loop, which increases constriction about the neck. This often produces surface abrasions, which eventually dry and darken, taking on a parchment-like appearance. There is frequently an inverted V-shaped furrow extending toward the point of suspension. If the noose is not tightly fitting or if the head leans away from the point of suspension, the suspending object may pull away from the neck on one side, leaving a mark that does not completely encircle the neck. In most circumstances, the marks are usually higher on the side of suspension. The characteristics of the marks on the neck are dependent on the ligature used; therefore, they are deep and narrow if the result of a wire but are nearly nonexistent if a towel or soft material is used. Natural attempts to release the ligature prior to unconsciousness occasionally may result in claw-type abrasions or even fingers entrapped under the ligature, leaving similar indentations. It is important to carefully examine and document the ligature mark.

After complete pressure is applied to the neck structures, loss of consciousness occurs quickly, usually in seconds. However, cessation of cardiac activity may not occur for as much as 15 to 20 minutes. The face may appear cyanosed or congested because of the overfilling of blood, but in some circumstances, it may be pale. Pressure on the base of the neck and areas in which the tongue is attached frequently causes the lower jaw to drop and the tongue to protrude from the mouth; with time, it dries and becomes blackened. As circulation ceases, blood drains to the dependent parts of the body. The combination of pressure and decreased oxygen can cause rupture of small vessels with the develop- ment of petechiae or Tardieu’s spots (ecchymotic hemorrhages) (Fig. 27-3) beneath the skin.

|

| Fig. 27-3 |

Fractures of the vertebrae are uncommon in hangings unless there is considerable force, as is seen in judicial hangings that are a common form of execution in many parts of the world. Fractures can also occur when the victim has jumped from a significant height. If fractures do occur, they are usually located in the upper cervical spine. The classic hanging fractures occur at C3 or C4, although this should not be confused to what has been called the “hangman’s fracture of C2” (Besant-Matthews, 2009).

The autopsy findings include the ligature mark, which is usually abraded and parchment-like and may show a specific pattern associated with the ligature. The deepest furrow is opposite the point of suspension and fades as it approaches the knot. Petechial hemorrhages are usually absent when the full weight acts on the body but may be present in varying degrees when the victim is only partially suspended. There is usually little focal bleeding into or between the soft tissues and muscles of the neck. Small fractures of the cartilage of the larynx or fracture of the hyoid bone may be observed. Frequently, postmortem lividity is a deep purple color because of complete oxygen depletion in the venous system.

Ligature Strangulation

Strangulation is a form of asphyxia caused by occlusion of the blood vessels of the neck as a result of external pressure on the neck causing cerebral anoxia. In ligature strangulation, pressure is applied to the neck by a ligature tightened by a force other than the weight of the body. Death is due to occlusion of the carotid arteries and jugular veins with resultant cerebral anoxia. Most ligature strangulations are due to assault or homicide, and suicides are very uncommon. Easily concealable weapons are often used as a ligature in combination with sudden attack. Certain victims, including children, the elderly, smaller individuals, the mentally or physically debilitated, and those intoxicated by drugs or alcohol, are more vulnerable and less capable of fending off the attack. Accidental ligature strangulations are rare and usually involve pieces of clothing becoming entangled in machinery. Children may also snag their clothing while climbing and playing on slides and become a victim of ligature strangulation.

Manual Strangulation

Manual strangulation, sometimes referred to as throttling, is asphyxia caused by pressure of the hands, forearm, or other limb on the neck, which compresses the internal structures causing occlusion vessels supplying blood to the brain. It is important to recognize that suicide is not possible by manual strangulation given that as unconsciousness occurs, the grip relaxes, blood flow is restored and consciousness returns. Again, certain victims such as children, the elderly, smaller individuals, the mentally or physically debilitated, and those intoxicated by drugs or alcohol are generally more vulnerable to and less capable of fending off such an attack. Injury or death by manual strangulation is always associated with violent assault and homicide.

At autopsy, the face appears congested in a large proportion of such deaths, and petechiae can be identified in the sclerae and conjunctivae as well as around the eyes and, at times, the cheeks. Abrasions and contusions can be seen on the neck and under the jaw. Fingernail marks may be identified on the neck. Hemorrhages may be seen in the strap (short) muscles of the neck and in the area of the thyroid gland. There may be fractures of the hyoid bone or thyroid cartilage depending on the amount of force used, such fractures being more common among elderly victims.

Law enforcement agencies have been known to use neck holds, including chokeholds or carotid sleeper holds, to restrain violent individuals. The arm or forearm is used to compress the structures of the neck, producing hypoxia and unconsciousness. In the “sleeper hold,” the forearm and upper arm are placed around the neck with the antecubital fossa sparing the midline of the neck. The carotid arteries and jugular veins are compressed. The free hand then grips the wrist of the arm creating a vicelike effect. If applied appropriately, decreased blood flow to the brain causes unconsciousness. When the hold is released, consciousness is restored within seconds (Dolinak, et al., 2005). It is important to recognize that the hold is used in violent and uncontrolled situations and, as such, death can occur from inadvertent compression of the airway or from prolonged use of the hold past unconsciousness, which can result in death from manual strangulation.

In chokeholds or bar-arm holds, the forearm or sometimes a flashlight or nightstick is placed across the neck while the other hand grips the wrist, pulling it back and causing collapse of the airway and displacement of the tongue to the back of the throat, occluding the hypopharynx. Airway and carotid artery obstruction causes decreased oxygen to the brain and unconsciousness. In some cases, injury such as fracture to the larynx or hyoid bone can occur. If the hold is held too long, death can occur as in manual strangulation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree