Marilyn R. Mouradjian*

Substance Abuse

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Discuss the historical trends and current conceptions of the cause and treatment of substance abuse.

2. Describe the current social, political, and economic aspects of substance abuse.

3. Describe the ethical and legal implications of substance abuse.

4. Detail the typical symptoms and consequences of substance abuse.

Key terms

addiction

dual diagnosis

harm reduction

initiation

intervention

mutual help groups

professional enablers

social consequences

substance abuse

war on drugs

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

Perhaps no other health-related condition has as many far-reaching consequences in contemporary Western society as substance abuse. These consequences include a wide range of social, psychological, physical, economic, and political problems. Health problems and disability associated with substance abuse total approximately $276 billion annually. Each year, it costs an estimated $1000 per person for health care, law enforcement, accidents, treatment, and lost productivity. More deaths, illnesses, and disabilities are attributed to substance abuse than to any other preventable health condition in the United States (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2004c).

The social consequences of substance abuse include its role in crime (due to disinhibition), need for money to buy substances, and specific theft of drugs. Many offenders commit crimes while under the influence of drugs, alcohol, or both. Between 35% and 50% of inmates in correctional facilities reported that they had been under the influence of drugs when their crime was committed. Furthermore, almost 75% of inmates report prior drug use (Bureau of Justice Statistics [BJS], 2005).

All aggregates in society are potentially affected by substance abuse problems. Infants exposed in utero to alcohol, amphetamines, or opiates are at risk for withdrawal syndromes and later developmental problems. Indirect social effects of substance abuse include relationship conflicts, divorce, spousal and child abuse, and child neglect. Although well intended, many local and national efforts to fight substance abuse are often inadequate and ineffective (Drucker, 1999).

In the past, alcoholism and drug addiction were considered to be problems of the urban poor; society and most health professionals virtually ignored them. Substance abuse problems now pervade all levels of U.S. society, and awareness has increased. Community health nurses must be knowledgeable about substance abuse because it is a problem that frequently intertwines with other medical and social conditions.

This chapter focuses on helping community health nurses recognize substance abuse in their clients and in the larger community. The chapter reviews historical trends, the causes of substance abuse, the most common symptoms of these disorders, and treatment options. The author suggests nursing interventions appropriate for assisting those with substance-related problems, in a community context.

Historical overview of alcohol and illicit drug use

During the twentieth century, fluctuations in the use of alcohol and illicit drugs were influenced by shifts in public tolerance and political and economic trends. In general, alcohol use gained more social acceptance than other drug use. Alcohol consumption in the United States was higher during World Wars I and II and decreased during Prohibition and the Great Depression. Alcohol use was highest during the 1980s when states lowered the drinking age to 18 years of age. Lawmakers became alarmed at the increased rate of drinking and the increased number of alcohol-related deaths among 18- to 25-year-olds after lowering the drinking age and thereby reversed the decision. During the late 1980s, alcohol use declined after the minimum drinking age was reinstated to 21 years of age. The decline in alcohol consumption through the 1990s and into the twenty-first century is attributed to less-tolerant national attitudes toward drinking, increased societal and legal pressures and actions against drinking and driving, and increased health concerns among Americans. The identification of, and response to, driving under the influence is an example of a shift in thinking from addiction as the primary concern to other problems linked with, for example, alcohol use. These problems are thus termed substance-related problems and have become a significant community concern.

Public attitudes and governmental policies also have influenced the history of illicit drug use. Although nineteenth-century physicians prescribed morphine for a large variety of ailments, the discovery of the addictive properties of cocaine and opiates led to increased governmental regulation at the beginning of the twentieth century. The Harrison Narcotic Act of 1914, and subsequent laws, lessened the medical profession’s control over the use of addictive drugs; the legislation specified that the physician could prescribe these drugs only in the course of general practice and not to maintain an addiction (Brecher, 1972). This limitation on the physician’s power to prescribe and dispense addictive drugs, and restrictions on the importation of narcotics, limited the supply of these drugs until the 1950s and 1960s. At that time, an increase in illegal drug trafficking caused heroin use to proliferate, particularly in inner cities.

By the 1970s, drugs were increasingly available. During this period, a counterculture population, composed largely of young people, focused their efforts on enhancing social justice, ending the Vietnam War, and lessening “repressive” sexual mores; many conceptualized drug use as a way to liberate the mind. Marijuana use took place in communal, social settings; alcohol use was less favored because it was associated with the “establishment” they were critiquing. Consequently, the use of hallucinogens, cannabis, and heroin spread beyond urban drug subcultures to the general population. Alarmed by the social and personal problems inherent in this change, the public grew less tolerant of drug use, and prevention and treatment programs were given more attention and resources. After peaking in 1979, illicit drug use decreased among most segments of the population throughout the 1980s, reaching a low in the early 1990s. Between 1995 and 2000, it increased slightly before dropping again in recent years (SAMHSA, 2005).

To combat concerns of the physical, social, and psychological impact of drug abuse and dependence, federal drug policy has emphasized law enforcement and interdiction—the war on drugs—to reduce the supply. Despite the large amounts of money spent toward reaching this goal, this strategy has been only somewhat effective (Drucker, 1999). Trends have shown renewed interest in prevention and treatment efforts to decrease the amount of illicit drug use in society and to lessen its impact (SAMHSA, 2004c).

Prevalence, incidence, and trends

The increasing recognition of the widespread effects of substance abuse has initiated extensive collection of data by multiple agencies. This section describes selected statistics and current trends. The U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health is an annual survey conducted by SAMHSA, which estimates the prevalence of illicit drug and alcohol use in the United States. Findings from a 2008 report include the following (SAMHSA, 2008):

Alcohol

• Young adults aged 18 to 25 years had the highest prevalence of binge drinking and heavy drinking. Among older age groups, the prevalence of current alcohol use decreased with increasing age, from 67.4% among 26- to 29-year-olds to 50.3% among 60- to 64-year-olds and 39.7% among people aged 65 years or older (SAMHSA, 2008).

Illicit Drug Use

About 14.2% of the general U.S. population over age 12 years were drug users in 2008, compared with 7.1% in 2001 (SAMHSA, 2008). In 2008, marijuana was used by 75.7% of current illicit drug users and was the only drug used by 57.3% of them. Illicit drugs other than marijuana were used by 8.6 million persons, or 42.7% of illicit drug users aged 12 years or older. Current use of other drugs but not marijuana was reported by 24.3% of illicit drug users, and 18.4% used both marijuana and other drugs (SAMHSA, 2008).

In 2008, 9.3% of youths aged 12 to 17 years were current illicit drug users: 6.7% used marijuana, 2.9% engaged in nonmedical use of prescription-type psychotherapeutics, 1.1% used inhalants, 1.0% used hallucinogens, and 0.4% used cocaine (SAMHSA, 2008). Marijuana was the most commonly used illicit drug, especially among teens (15.2 million past month users). Interestingly, rates of current use among youths 12 to 17 years old declined significantly from 2002 to 2008 for several specific drugs including marijuana (from 8.2% to 6.7%), cocaine (from 0.6% to 0.4%), prescription-type drugs used nonmedically (from 4.0% to 2.9%), pain relievers (from 3.2% to 2.3%), stimulants (from 0.8% to 0.5%), and methamphetamine (from 0.3% to 0.1%).

Nonmedical Use of Prescription-Type Psychotherapeutics

There is a significant increase in the lifetime nonmedical use of pain relievers (20.8% of individuals aged 12 years and older) specifically Percocet, Percodan or Tylox, Vicodin, Lortab or Lorcet, Darvocet, Darvon or Tylenol with codeine, propoxyphene or codeine products, oxycodone, and hydrocodone (SAMHSA, 2008).

Hallucinogen, Inhalant, Needle, and Heroin Use

PCP, LSD, psilocybin, and ecstasy usage increase significantly after age 17 years (SAMHSA, 2008). Approximately 2% of individuals aged 12 to 25 years abuse inhalants. The inhalants of choice are amyl nitrite, “poppers,” followed by glue, shoe polish, or toluene; correction fluid, degreaser, or cleaning fluid; gasoline or lighter fluid; and spray paints and other aerosols (SAMHSA, 2008).

Gender Differences

Female illicit drug use for ages 12 years and older is increasing while there is little change in male illicit drug utilization. According to SAMHSA in 2008, males were more likely to be current illicit drug users. The rate of current illicit drug use among females (12 years and older) increased from 5.8% (2007) to 6.3% (2008) while the rate for males, during the same period, did not change significantly (10.4% and 9.9% for 2007 and 2008, respectively). Current marijuana use among females also increased (3.8% to 4.4%) but did not change significantly for males (8% and 7.9%, respectively).

Demographics

Demographic correlates show some regional, racial, and gender differences and changes over the past few years. For example, people living in the West have the greatest percentage of past month drug use at 12.9%, compared with 9.7% for those in the Midwest, 9% for those in the Northeast, and 9% for those in the South. Additionally, rates of current illicit drug use vary significantly among major racial/ethnic groups. Rates were highest among American Indians or Alaska Natives (19.5%), followed by African Americans (16.9%), whites (14.4%), and Hispanics (12.3%). Asians had the lowest rate at 7.4% (SAMHSA, 2008). Visit the SAMHSA Office of Applied Studies website at www.oas.samhsa.gov/nhsda.htm for more information about substance abuse trends and statistics.

Trends in Substance Use

Research has revealed that problems associated with substance use may or may not relate to classically or clinically defined dependence or addiction. Many are turning to recovery before they have developed physiological dependence. Thus many in the field have begun to differentiate between use and misuse (misuse being interchangeable with abuse), and these terms now appear in the literature. This section describes significant trends in substances that are being abused and discusses substance abuse among special populations.

Healthy People 2020 and Substance Abuse

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS, 2009) set goals and objectives related to substance abuse in Healthy People 2020 (USDHHS, 2000). The objectives consist of norms and targets for the decade for health conditions for the U.S. population. The use of harmful substances is indirectly and directly related to all of the leading health indicators (i.e., tobacco use, alcohol and other drug abuse, physical activity, overweight and obesity, mental health, injury and violence, environmental quality, responsible sexual behavior, immunization, and access to health care). The Healthy People 2020 table presents selected objectives and targets from Healthy People 2020 related to substance abuse.

On review, there were mixed results related to progress toward the Healthy People 2010 objectives. Whereas overall drug use, particularly among adolescents, declined, alcohol-related motor vehicle deaths remained steady, at about 30% of all fatalities (USDHHS, 2009). A disturbing trend is the large increase in the use of methamphetamines, steroids, and inhalants by young people.

Methamphetamine

Since 1997, methamphetamine (MA) has evolved as the most widely produced controlled substance in the United States. It is appearing in mass quantities, in part because of the ease in which the fertilizer anhydrous ammonia can be converted into MA; this has resulted in attracting more individuals into this clandestine business. Illegal street forms of the drug, often called crank, crystal, or meth, are available as a powder that can be injected, inhaled, or taken orally. In addition, a smokable form, known as ice or glass, is widely available. Currently, the preferred route of administration is by injection. This is possibly due to the undesirable physical difficulties related to smoking MA (e.g., damage to the nasal tract, coughing up blood, or difficulty breathing) (Cretzmeyer et al., 2003).

There is new attention being paid to MA manufacture and use because of the alarming increase in rates of abuse. The incidence of MA use rose steadily between 1990 (164,000 new users) and 2000 (344,000 new users). The new users during this time were approximately evenly split between 12- to 17-year-olds and 18- to 25-year-olds. This shift in age distribution from previous decades was reflected in the average age of new users, which fell from 22.3 years in 1990 to 18.4 years in 2000 (SAMHSA, 2004c). Hospital admissions for abuse of stimulants, mainly MA, increased from 1% to 7% between 1992 and 2002 (SAMHSA, 2003).

The pleasurable effects of MA are due to the release of high levels of dopamine in the brain, leading to increased energy, a sense of euphoria, and increased productivity. Short-term effects are increased heart rate, insomnia, excessive talking, excitation, and aggressive behavior. Prolonged use results in tolerance and physiological dependence. There are multiple negative effects for users of MA, their families, and communities. It appears to damage the brain in ways that are different from, and more severe than, damage from using other drugs. Currently, there is rudimentary understanding of ways it affects the brain, but it is known that profound neurological changes occur even with first administration (Volm and de Araujo, 2004). Negative consequences range from anxiety, convulsions, and paranoia to brain damage (Block, Erwin, and Ghoneim, 2002). Use of MA is associated with an increased incidence of violence such as domestic abuse, homicide, and suicide, whether as a victim or as a perpetrator (Logan, Fligner, and Haddix, 1998).

MA is used predominantly by white young persons, with an overrepresentation of females. Thirty-six percent indicate that they were first introduced to the drug when they were under 16 years of age (SAMHSA, 2004a). Rates of admission for treatment of methamphetamine vary by region. The highest is Utah; however, most areas of the country are reporting an exponential rise of its manufacture and use.

The impact of MA abuse on communities, families, and social networks is considerable. Reported use is highest among 20- to 29-year-olds. This group often has young children, which puts these children at risk for abuse and neglect. The incidence of prenatal use is also rising, increasing the risk for children to be born with developmental problems, aggression, and attention disorders (Logan et al., 1998). Furthermore, exposure to combustible secondhand fumes puts children at risk for not only complications related to primary ingestion but also fatalities and injuries related to the highly combustible nature of the chemicals used in manufacture of the drug (Haight et al., 2005). Another pediatric issue is the growing number of teens recruited in the manufacture and selling of MA (Block et al., 2002).

Steroids

Evidence suggests that steroid use among adolescents is decreasing. In its annual survey used to assess drug use among our nation’s teens in 2008, Monitoring the Future found that 0.9% of eighth graders, 0.9% of tenth graders, and 1.5% of twelfth graders had used anabolic steroids during the previous year. Steroid use is more commonly utilized in athletes and other individuals willing to risk potential and irreversible health consequences to build muscle (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2008). Data are scarce on the extent of steroid use by adults, but it has been estimated that hundreds of thousands of people aged 18 years and older use anabolic steroids at least once a year. Among both adolescents and adults, steroid use is higher among males than females (Gruber and Pope, 2000).

Use of steroids by popular sports figures may have influenced a generation of teenage athletes, girls as well as boys, to put themselves at risk. The health consequences of steroid use are well documented. Boys experience sexual changes, including decreased sperm count, impotence, shrinking of testicles, and difficulty urinating. In females, steroid use can manifest as masculinization, often producing increased facial hair and menstruation problems (Gruber and Pope, 2000). There are other more potentially fatal risks, including blood clots, liver damage, premature cardiovascular changes, and increased cholesterol (Sullivan, Martinez, Gennis et al., 1998). Evidence also points at behavioral changes leading to an increased potential for suicide and aggressive and risky behaviors among steroid users (Pope, Kouri, and Hudson, 2000). Most negative effects are reversible on discontinuation of the drug. Collaborative treatment programs that monitor both psychological and physical issues, including consideration of the drug use route as injection, are necessary to combat steroid abuse.

Inhalants

Inhalants are defined by mode of administration (inhalation of fumes) and encompass a range of substances as diverse as glues, aerosols, butane, paint thinner, and nail polish remover. These products are inexpensive, legal, and easy to obtain, making them attractive to younger adolescents who have less access to illicit drugs.

Use of inhalants has consistently been highest among eighth graders, but a recent survey showed that inhalant use has increased among older teens as well. Further, studies monitoring drug- and alcohol-related emergency department admissions show that the largest increases in admission between 1995 and 2002 were for inhalants (186%) and amphetamines (166%) (NIDA, 2005).

Adolescent substance abuse

Youth are a particularly susceptible aggregate for substance abuse. Individuals between 18 and 25 years of age have the highest prevalence of illicit drug use during their lifetime (65% of the population). One positive development is that teen use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco has declined since the peak levels in the mid-1990s. Indeed, 30-day prevalence of smoking has declined by 56% in eighth grade, 47% in tenth, and 32% in twelfth. It is noteworthy, however, that this significant decline in adolescent smoking and use of smokeless tobacco has decelerated sharply and seems to be on the verge of halting among tenth graders (NIDA, 2005). Cigarettes continue to be highly available to the young, and concerned groups continue to monitor advertising that targets new potential smokers, such as youth and women.

Trends in alcohol use by American teens are mixed. Throughout the early part of the century, there were drops in several indicators of alcohol use at all grade levels. In 2004, however, most drinking measures showed slight increases among twelfth graders (NIDA, 2005).

Most of the movement in teen substance use has been in a downward direction, but generally the declines have been marginal (Johnston et al., 2005). Between 1995 and 2002, there was no consistent increase or decline in marijuana users. However, the percentage of adolescents reporting that it is easy to obtain marijuana declined slightly, from 55% to 53.6% (SAMHSA, 2003). In addition, initiation of both LSD and ecstasy declined. Use of PCP, or phencyclidine, has been at low levels for some time, and use fell further in 2004. The resurgence of inhalant use among the eighth graders was one of the more troublesome recent findings, as was the continued rise in use of the highly addictive narcotic drug oxycodone (OxyContin) among high school seniors and eighth graders (NIDA, 2005).

In order to effectively plan for the present and future needs of the community, the community health nurse needs the most current overall perspective. Information on the prevalence, incidence, and trends in the amount and types of substance abuse at the general, state, and local levels is readily available on the Internet. As harmful, illicit substances come in and out of vogue, particularly among young people, the community health nurse needs a good understanding of drug culture, terminology, and differing signs and symptoms.

Conceptualizations of substance abuse

Conceptualizations of substance abuse and dependence have changed over the years, often for political and social reasons rather than for scientific reasons. Some conceptualizations focus on the phenomenon of addiction, which is manifested by compulsive use patterns and the onset of withdrawal symptoms when substance use is abruptly stopped. Other views focus on the problems resulting from the substance use itself, regardless of whether an addictive pattern is present. Problematic consequences of substance use include intoxication, psychological dependence, relational conflicts, employment or economic difficulties, legal difficulties, and health problems. For example, addiction need not be present for individuals to experience legal consequences of illicit drug use, such as driving while intoxicated, or alcohol- or drug-related domestic violence.

Drawing fine distinctions among ideas of dependence, addiction, and abuse concerning substance use may seem irrelevant if there is evidence that the substance use has become problematic. However, broadly labeling all habitual or compulsive behavior patterns as addiction or dependence may obscure the fact that interventions could precede the development of addiction, for example, in cases where use has become misuse and a problem is evident. It is also becoming increasingly evident that specific interventions may be needed for each separate addictive problem (e.g., overeating and gambling). Moreover, in each specific group, there is wide individual diversity.

Definitions

The term substance abuse came into common usage in the 1970s. Earlier conceptualizations generally focused on either alcoholism or drug addiction as singular addictive disorders. Most substance abuse theories identify core commonalties that occur in regard to use of a variety of different substances or in relation to compulsive behavior syndromes (Leshner, 1997). There is also an emphasis on relapse prevention that may include moderate use goals and abstinence (Larimer and Marlatt, 1990).

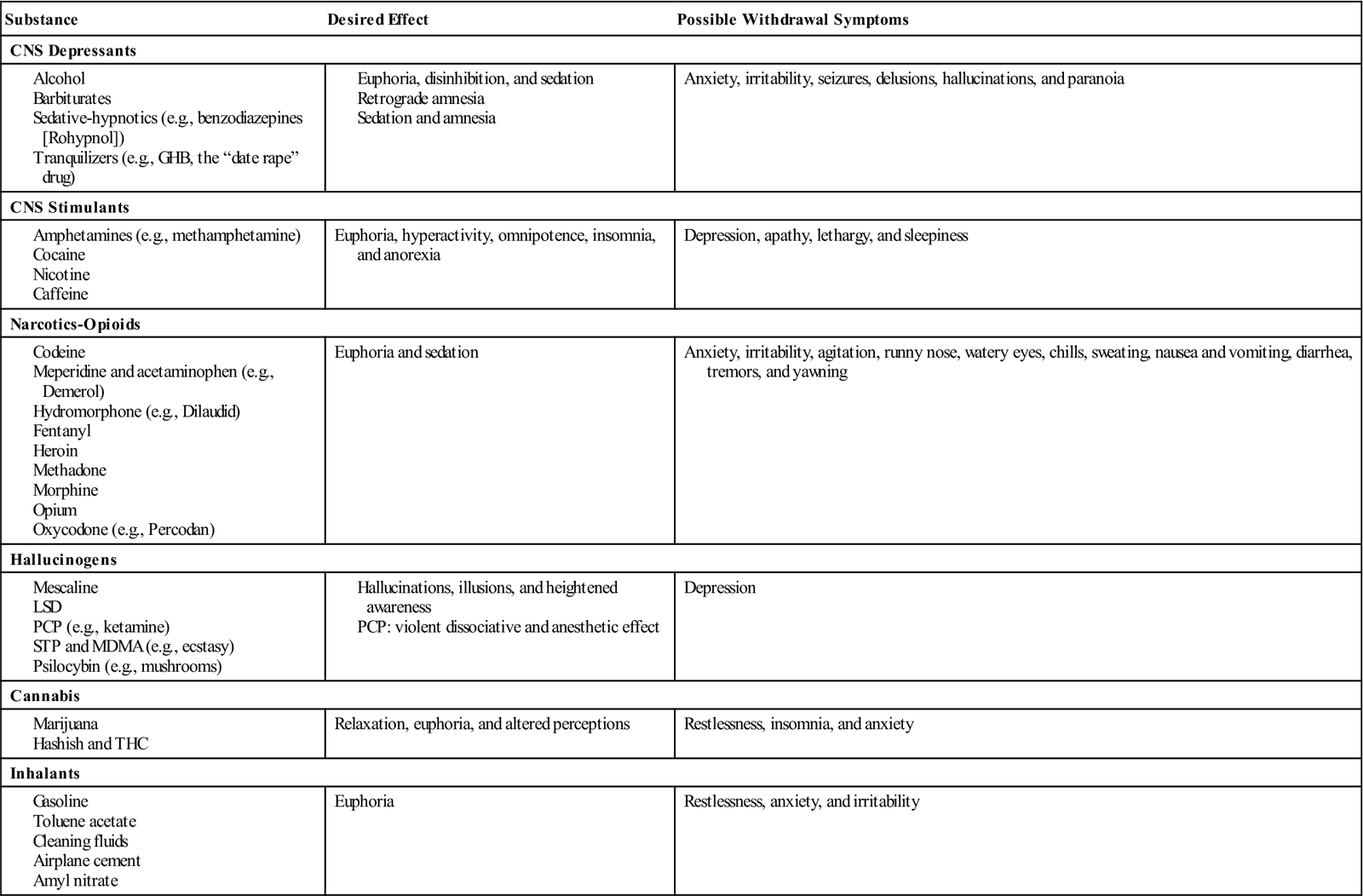

There remains debate about how substance use and substance abuse should be defined and what substances should be included under each definition. Traditional conceptualizations of substance abuse focus solely on alcohol and illicit street drugs. Other conceptualizations include prescription medications such as tranquilizers or analgesics. In eating disorders such as bulimia and compulsive overeating food is viewed as the abused substance. Table 26-1 shows a classification scheme for commonly abused substances.

TABLE 26-1

Classification of Commonly used and Abused Substances

Modified from Faltz B, Rinaldi J: AIDS and substance abuse: a training manual for health care professionals, San Francisco, 1987, Regents of the University of California. Used with permission.

In addition to varying in their abuse potential, substances vary in their degree of potential harm to those who use them and to others in the immediate environment. Tobacco is an example of a substance that is unsafe to the smoker and to those who inhale secondhand smoke. Those who abuse alcohol may also harm others by driving under the influence, and lowering of inhibitions may foster violent activities in some (e.g., child or partner abuse).

Integrating the various opinions regarding the diagnosis of substance abuse, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) has classified substance use disorders as either “dependence” or “abuse” (APA, 2000). The APA focused on the following psychoactive substances that affect the nervous system: alcohol, amphetamines, caffeine, cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, nicotine, opioids, phencyclidine, sedatives, and hypnotics or anxiolytics. Substance use disorders can also be categorized as being in partial or full remission. A diagnosis of substance abuse indicates a maladaptive pattern of substance use that is manifested by recurrent and significant adverse consequences related to repeated use of a substance. These adverse consequences include failure to fulfill major role obligations, repeated use in physically hazardous situations, multiple legal problems, and recurrent social and interpersonal problems.

The criteria for the diagnosis of dependence include a cluster of cognitive, behavioral, and physiological symptoms that indicate continued use of the substance despite significant substance-related problems. A pattern of repeated, self-administered use results in tolerance, withdrawal, and compulsive drug-taking behaviors, which are frequently accompanied by a craving or strong desire for the substance. This craving then motivates the user to be preoccupied with supply, money to purchase drugs, and getting through time between periods of use, all of which take up mental energy, effort that is diverted from work or school, and connectedness to significant others. This is how the use becomes problematic and how others around the user become confused and eventually often feel rejected, hurt, ignored, angry, or even responsible for the user’s behavior.

Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Dependence

The APA has established the following criteria for substance dependence: the maladaptive pattern of substance use, leading to clinically significant impairment or distress. Three (or more) of the following criteria must be exhibited anytime within the same 12-month period:

1. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following:

a. A need for markedly increased amounts of the substance to achieve intoxication or desired effect

b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of the substance

2. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following:

a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance

b. The same (or closely related) substance is taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms

3. The substance is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than intended.

4. There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control substance use.

6. Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced.

8. Specify if with or without physiological dependence (e.g., tolerance or withdrawal) (APA, 2000).

Substance abuse must be understood and differentiated from substance dependence. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision, uses the following criteria when diagnosing substance abuse, which is a maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by one (or more) of the following, occurring with a 12-month period:

Etiology of Substance Abuse

Substance abuse has an impact on virtually every aspect of individual and communal life, and many institutions and academic fields have addressed it. Several theories attempt to explain the cause and scope of these problems and offer solutions. Some theories address individual, physiological, spiritual, and psychological factors. Others deal with social influences involving family, ethnicity, race, access to drugs, environmental stressors, economics, political status, culture, and sex roles. Most theories suggest that a combination of factors is the underlying impetus for substance abuse.

Although physiological, medical model theorists have defined alcoholism as a loss of control over drinking or an individual malfunction, the cause of alcoholism was ambiguous in the past (Brown, 1969; Keller, 1972). Although previous research studies have suggested a link between genetics and alcoholism, there is growing evidence that genetic variations may contribute to the nature of alcoholism within families (NIDA, 2006).

Individual and environmental factors also contribute to an increased risk for alcohol abuse. On the individual level, a person’s inherited sensitivity to alcohol is a predictor for the development of alcohol abuse. Two broad personality dimensions are also associated with an increased risk for alcohol abuse. Impulsivity and ease of disinhibition add to risks for substance abuse. Proneness to anxiety and depression are also risks, and these comorbidities are not well understood. Alcohol expectancies (i.e., beliefs about anticipated consequences of drinking) are also a predictor of alcohol abuse. If one expects a certain effect, such as relief, one is more likely to feel it after use of a drug. The satisfied expectancies may set up neural pathways that are interpreted as pleasurable.

Medical models of alcoholism and other substance abuse conditions may not provide an understanding of commonalities among addictive behaviors (e.g., excessive drinking, gambling, eating, drug use, and sexual behavior). Cross-addiction, or multidrug use, is more prevalent now than in the past, and more studies point to the presence of both automatic and nonautomatic factors in physiological and psychological dependence. Specific biological medical models are giving way to multicausal models.

In the biopsychosocial model, risk factors interact with protective factors to develop a predisposition toward drug or alcohol use. This predisposition is then influenced by exposure to the substance, availability, and the experiential interpretation of the drug experience (e.g., pleasant or unpleasant). Continued availability of the substances and a social support system that enables or supports their use is also necessary. These factors combine to determine whether addiction develops and is maintained.

Sociocultural and political aspects of substance abuse

Within community settings, substance-related problems are not always easy to identify. For example, the consequences of the sale and use of crack cocaine in an inner-city, African-American neighborhood may be apparent through media attention. The traffic of these drugs into the middle classes, on the other hand, is less easily recognized. The increasing tendencies of elderly persons to rely on alcohol and other, even illicit, drugs may be shocking to some nurses. It can be understood, however, contextually and may be the result of multiple factors such as isolation, fears, uncontrolled chronic pain, anxiety, and sleep disturbances. Nurses must incorporate sociocultural and political dimensions into caring for clients in the community. Nurses must also possess knowledge that is useful in countering media stereotypes and can model a more holistic, multifaceted approach to prevention and management of substance abuse.

Although there are subcultural and regional variations, drinking norms of the dominant culture in the United States are relatively permissive. Traditional ethnic ceremonial and symbolic substance use patterns vary significantly. As acculturation occurs, however, cultural definitions of “appropriate” use of alcohol and drugs have been dulled, leaving a void regarding social expectations. Subcultural groups such as gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender persons have often had a social center that was a bar, and alcohol use was historically a way of demonstrating and celebrating differentiation from a more repressive majority. These cultural conditions create ambiguity in clearly determining when a substance abuse problem exists. Furthermore, each subculture may define abuse differently. It can be theorized that stigmatized minorities might be under more stress, and perhaps more likely to use substances, but this cannot be assumed in any individual case.

A particular drug experience can be understood as an interaction between the individual’s subjective mood and the actual pharmacological effects of the drug, but this interaction does not take place in a vacuum. Rather, the expectations of a drug’s effect are shaped by the user’s culture and involve the adoption of roles taught by more experienced users and reinforced by other social groups, including health care providers in some cases (Montagne and Scott, 1993).

Substances are also given economic value and are bought and sold as commodities in a variety of social arenas, both legal and illegal. The ways in which drugs, including nicotine, medications, and alcohol are produced and distributed among the various segments of the population are determined largely by economic, cultural, and political conditions. For example, the economic realities of poor Colombians and Peruvians who rely on the growth and production of the coca leaf for financial survival can be understood as a confluence of larger, society-level and individual-level factors. The drug trade is very lucrative for some; it raises their societal status, gives them access to material things, and provides an enhanced sense of power in that society. Among urban poor minority youth in the United States, the fact that drug trafficking often precedes drug use suggests that involvement in the drug trade satisfies a need for status and economic power (Greenberg and Schneider, 1994).

These changes in power can have other consequences as various subgroups attain and maintain status. A group without cultural values, or with competing cultural values, suffers from chaos and disorganization. Competing value systems lead to cultural disintegration and a sense of powerlessness and hopelessness. The group becomes susceptible to forces that further threaten the group’s ability to survive. When they are unable to organize or determine a collective direction because of conflicting values, the group and its members are separated and disempowered. The history of cocaine abuse and dependence among people of color is an example of how these conditions are interrelated. Indeed, cocaine use was epidemic in the 1980s and early 1990s, with crack cocaine most prevalent in poor communities, but its use has declined markedly in recent years (SAMHSA, 2004c).

Course of substance-related problems

There is no predictable course of addictive illness and no “addictive personality type.” When habitual use is well established, behaviors may be clinically visible and similar; this has led to assumption of a singular, addiction-prone personality. However, not everyone who initiates drug or alcohol use will progress to dependency or display associated behaviors. Because the path from initiation to dependency is multidimensional, the context of client and community experiences is key to understanding and responding to problems encountered. Nurses need to take a comprehensive health and substance use history and place this in a context of cultural, historical, family, and social factors. Neither addiction nor dependency is a unitary phenomenon with a single isolated cause; rather, it is the result of interactions among a host of variables.

The assessment process should include consideration of the triad: the person, the substance, and the context or environment. The person assessment includes demographic information, medical history, comorbidities, and known perceptions and meanings the individual displays. The drug assessment includes the qualities of the substance itself, physiopharmacological effects, pattern of use, availability, and toxicity. Context assessment should include family, social, employment, legal, cultural, and economic contingencies.

Hanson, Venturelli, and Fleckenstein (2002) categorize users of illicit substances as experimenters, compulsive users, or “floaters.” Experimenters begin using substances largely because of peer pressure or curiosity; they are usually able to set limits. In contrast, compulsive users devote much of their time and energy to getting high and tend to immerse themselves in conversations and social interactions around drugs and alcohol. “Floaters” focus more on using other people’s substances and generally have light to moderate use. This does not explain the meaning that substance use has for the individual, however, nor what kinds of experiences and perceptions are associated with use. The subjective experiences of using particular substances and other issues such as genetic predisposition, discrimination, past trauma, family strife, and economic status make each case of substance use or misuse as unique as one’s fingerprint.

Genetic traits have been found to be associated with addiction to certain substances. For example, people of Chinese or Japanese extraction may become ill after ingestion of even small amounts of alcohol. A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) that encodes opiate receptors is more frequent among some heroin addicts, and an SNP that encodes dopamine receptors is more frequent in some alcoholics. Certainly there is a genetic and disease component to addiction, implying that prevention efforts can be more efficient when targeted at vulnerable individuals. As a result, prevention efforts should focus on children of addicts, who should be advised not to experiment (Goldstein, 2001).

The progression from initiation to continuation, transition to abuse, and, finally, addiction and dependency varies. Individuals often describe a progression that began with initiation through social interactions. For some, the substance and setting is reinforcing and primes the individual for a pattern of use. For others, the experience will be unpleasant enough to prevent further use. It cannot be assumed, however, that an unpleasant initiation will always be preventive. In the case of stimulants, such as MA, the drug produces such strong feelings of euphoria, alertness, control, and increased energy that future use is enticing, especially when the drug is easily accessible (Cretzmeyer et al., 2003).

The continuation stage of substance abuse is a subsequent period in which substance use persists but does not appear to be detrimental to the individual. In stimulant abuse, continued use often occurs in a binge pattern. Individuals are able to exercise some control over use, but use becomes more frequent. Neither the individual nor the social network views use during this stage as problematic.

A critical point is the transition stage from substance use to substance abuse. There may be evidence to both the users and their social networks that the use of the substance is having adverse effects. During this stage, users begin to use more often and in more varied settings. Rationalizations that deny the seriousness and consequences of the substance use are commonly constructed during this stage.

The research on correlates and antecedents of substance abuse points to a variety of personal and social motivations. For many young people, motivators are the attraction of a rebellious subculture, peer pressure, and nationwide fads. Considerable research exists on the self-medication aspects of individuals with comorbid mental illnesses. Once the addiction is established, unpleasant physical and emotional withdrawal symptoms are strong motivators to continue use. Abstinence in the stimulant abuser can result in symptoms such as depression, lethargy, and anhedonia (i.e., inability to feel pleasure). The depression experienced by the user when not using stimulants is contrasted with the recalled euphoria produced by the use of the drug. These factors, coupled with associated cues, help initiate the cycle of binge use, with increased craving and continued self-administration to relieve symptoms. Brain imaging techniques have demonstrated that abuse of drugs such as cocaine and amphetamine produce immediate and long-lasting physical changes that are likely to contribute to the maintenance of dependency (Obert, London, and Rawson, 2002).

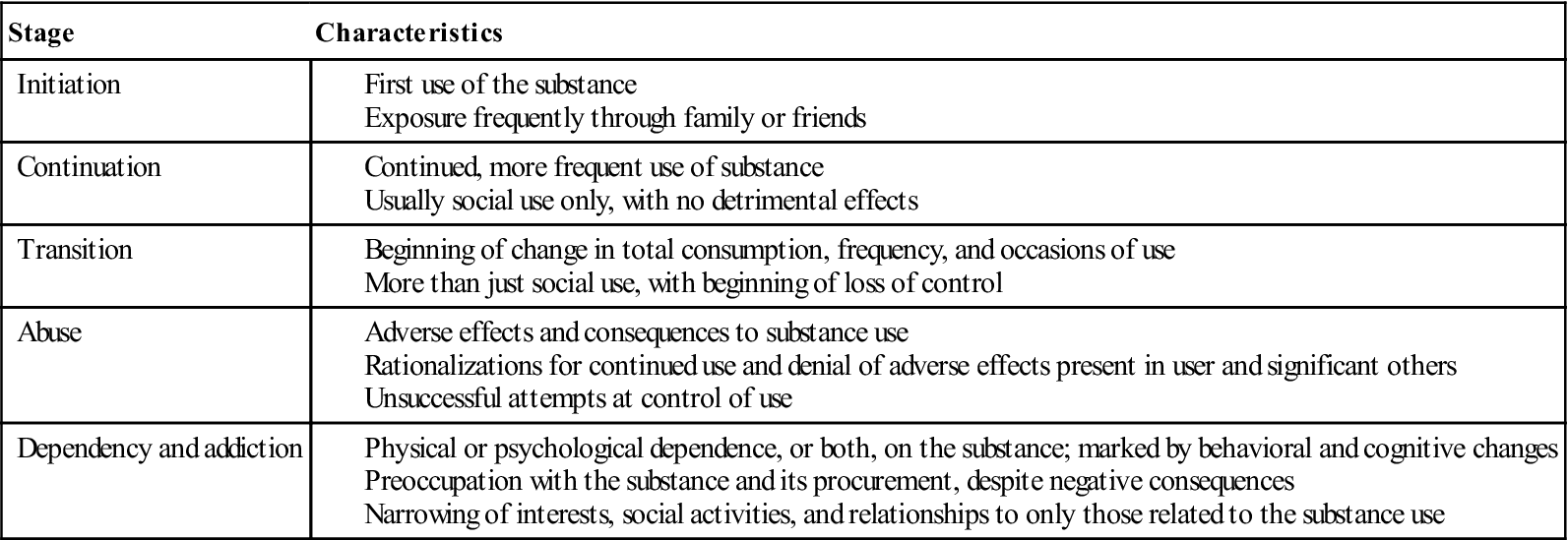

The development of addiction or dependency is marked by changes in both behavior and cognition. There is an increasing focus on the substance and a narrowing of interests, social activities, and relationships. The process of becoming dependent or addicted requires the individual to deny or ignore evidence or information that may challenge their behavior or rationalization of their behavior. There is a preoccupation with the substance and its procurement during this stage, even in the face of negative consequences. Table 26-2 outlines the stages in the process of stimulant addiction.

TABLE 26-2

Typical Course of Addictive Illness: Stages in Continuum from Initiation to Dependency

Legal and ethical concerns of substance abuse

For the past 30 years, the United States has pursued a drug policy based on prohibition and the active application of criminal sanctions against the use and sale of illicit drugs. During this time, the number of criminal penalties for drug offenses has climbed to 1.5 million offenses. There has also been a tenfold increase in imprisonment for drug charges since 1979, despite an overall decline in drug prevalence (BJS, 2002).

This increase in drug-related imprisonment is a result of harsher enforcement policies and longer mandatory sentences for possession of smaller quantities of drugs. Although some individuals are in prison for violent crimes or major drug trafficking, many drug offenders are arrested for small-scale drug deals made to support their personal use (BJS, 2005).

Alcohol use and abuse are different issues because the possession and sale of alcoholic beverages is only illegal if the individual involved is a minor. Concerns arise when individuals are intoxicated during work, while driving, or in situations that may affect the welfare of others. Legal penalties have increased for driving under the influence of alcohol because groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) influence legislation.

Drug testing, as part of preemployment assessment and random testing during employment, has become commonplace. Beginning in 1986, federal legislation, such as the Drug-Free Workplace Act and the Omnibus Transportation Employee Testing Act, has authorized drug and alcohol testing in specific job classifications. Although employees’ attitudes toward workplace drug testing are mixed, it has been shown to have a positive effect, and currently about 90% of large U.S. companies have a drug screening policy in place (Levine and Rennie, 2004; Sweeney and Penner, 1997). There is evidence that the most effective deterrent to drug abuse in workers is a comprehensive program combining testing with an employee assistance program, supervisory training, employee education, and a clearly written substance use policy (Quazi, 1993). The legal conflict in testing is its opposition to rights of privacy; therefore testing is random rather than universal (Levine and Rennie, 2004).

One area that has also received the attention of the legal system is the use by pregnant women of substances known to increase risks to the fetus in terms of future long-term developmental and behavioral problems. Pregnant addicts have been imprisoned and forced into treatment, and their children have been removed from their custody after birth. Many treatment providers and patient advocates view this approach as punitive and counterproductive to assisting these women and their children. There is concern that such sanctions may prevent addicted women from seeking treatment, for fear of legal consequences (Chavkin et al., 1998; Paone and Alpern, 1998).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Healthy People 2020

Healthy People 2020 Ethical Insights

Ethical Insights