Learning outcomes

By the end of this section, you should know how to:

▪ prepare the patient for this nursing practice

▪ collect and prepare the equipment

▪ administer drugs via a nebuliser, either in the community or in an institutional setting

▪ maintain equipment safely before and after nebulisation

▪ document drug administration (Nursing and Midwifery Council 2004b).

Background knowledge required

Revision of anatomy and physiology of the respiratory system

Revision of ‘Oxygen therapy’ (seep. 245)

Revision of ‘Administration of medicines’ (seep. 13).

Revision of local policy on nebuliser therapy.

Indications and rationale for using nebuliser therapy

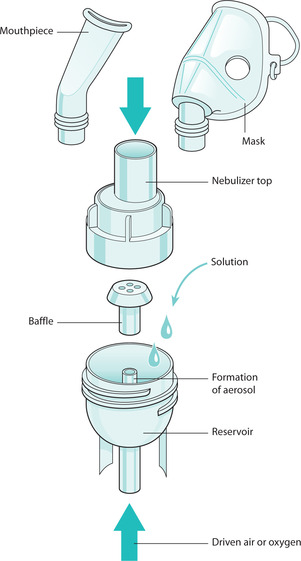

Nebulisers allow drugs to be administered directly into the lower respiratory tract. Drugs are usually available in solution, in single use containers called nebules. A nebuliser attached to a flow of air or oxygen converts the solution of a drug into an aerosol for therapeutic inhalation (British Thoracic Society 2004). The nebuliser will convert the drug into respirable particles that are small enough (2–5 microns in diameter) to reach the bronchioles. Lung deposition of the drug will be dependent upon the particle and droplet size, the type of nebuliser chamber, the volume of fluid, the flow rate of gas driving the nebuliser as well as the patient’s respiratory pattern. Treatment with nebulisers aims to deliver a therapeutic dose of a drug within a reasonably short period of time, i.e. between 5 and 10 minutes (British Thoracic Society 2004). Nebulisers can be useful when a large dose of a drug is required, or if a patient is unable to use any other device to inhale a drug, often in an acute situation. Nebulised drugs can be used without the need for the patient to co-ordinate breathing with inhalation, unlike using inhalers. Occasionally drugs for inhalation are unavailable in other forms of inhalers.

Nebulised drugs are used for patients with primary respiratory diseases such as asthma (Rees & Kanabar 2006) and also for patients with other diseases with respiratory symptoms, such as cancer or heart failure. Thus, the nebuliser can be used in acute, emergency situations such as acute asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), in primary health care or institutional settings. Equally, routine use for chronic disease management or palliative care can also occur in different care settings.

Common reasons for using nebulisers are:

▪ to administer bronchodilators, e.g.

— asthma

— COPD

▪ to administer an antibiotic (British Thoracic Society, 2003 and British Thoracic Society, 2004, Rees & Kanabar 2006), e.g.

— cystic fibrosis

— HIV.

The drug and driving gas for the nebuliser is prescribed by a medical practitioner and is often administered by the nurse. Sometimes treatment will be co-ordinated with chest physiotherapy. Compressed air is the most common driving gas used although high-flow oxygen may be used during an acute asthmatic event. A flow rate of 6–8L min−1 is required for either air or oxygen to ensure the drug particle size is small enough to allow lung deposition and drug effectiveness. For patients who have acute severe asthma, it is recommended that the driving gas is oxygen, to prevent desaturation of oxygen during nebulisation. For patients who have COPD, it is recommended that the driving gas is air to prevent diminishing the hypoxic drive leading to hypercapnia.

If long-term domiciliary nebuliser treatment is needed, the patient may become efficient in his or her own self-care using nebuliser treatment at home, with access to a local nebuliser service for ongoing support and education as well as maintenance of equipment.

There are currently three main types of nebuliser with research ongoing to create ones that have improved efficiency of drug delivery (Esmond 2001):

▪ jet: is most commonly used

▪ ultrasonic: is a more expensive system

▪ adaptive aerosol delivery: provides more precise drug delivery.

The decision to use a mask or mouthpiece depends upon the individual patient and the drug being administered. Some patients may be unable to hold a mouthpiece and so a mask would be more suitable. Some drugs have side effects and it is recommended that they are used in conjunction with either a mask or mouthpiece. For example, anticholinergic drugs (e.g. Ipratropium Bromide) can cause eye problems (glaucoma) and are better suited to a mouthpiece (British Thoracic Society 2004). It is important to follow the manufacturer’s instructions to ensure the most appropriate delivery devices and equipment are used to maximise drug delivery and minimise side effects to the patient.

For some patients requiring nebulisation, it is important to measure Peak Expiratory Flow Rate (PEFR) before and after nebulisation to measure the effectiveness of drug administration. It is commonly required in patients with asthma (Rees & Kanabar 2006).

Equipment

Equipment1. Prescribed air supply: most commonly an electric or battery-operated air compressor

2. Prescribed oxygen supply, either piped or in cylinders

3. Oxygen tubing

5. Mouthpiece or appropriate oxygen mask (Fig. 26.1)

6. Prescribed drugs

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access