CHAPTER 26. Bite Mark Injuries

Gregory S. Golden

Forensic odontology is the branch of dentistry that deals with the collection, evaluation, and proper handling of dental evidence to assist law enforcement as well as civil and criminal judicial proceedings. Three main areas encompass the scope of forensic dentistry:

• Identification of unknown deceased

• Documentation and analysis of bite mark evidence

• Examination of oral-facial structures for determination of injury, possible malpractice, or insurance fraud

Certainly in the field of nursing, healthcare personnel occasionally find themselves providing medical care for the recipient of single or multiple bites that have been inflicted by another individual, animal, or, on rare occasion, self-inflicted. The practical aspects of collecting evidence from bites and documenting bite mark injuries falls under the purview of forensic nursing because many of these injuries become important as evidence later in judicial settings. For this reason, recognizing bite marks and applying the clinical protocol for documenting and handling bite mark evidence are essential components for the forensic nurse examiner.

Psychological Aspects of Biting

Crimes with an element of violence (rape, homicide, battery, child and elder abuse) have been identified as those most associated with biting events (Pretty, 2000). The psychological factors that motivate perpetrators of bites have been identified as varying themes of power, control, potency, and anger. The emotional overload and catharsis that occur can block any memory of the biting event and can suspend logical, rational behavior (Walter, 1985). Emerging research on domestic violence offenders who are prone to biting has identified numerous additional behavioral factors correlated with battery, abuse, alcohol use, emotional insecurity, and features of antisocial and borderline personality disorders (Murphy, 1994). In contrast to the previous situation is the event wherein the victim of the abuse bites the perpetrator. Although there are certainly fewer psychological implications in this situation, the act of biting nevertheless occurs as a response to motivational stimuli, especially in defending one’s own life. Whatever the circumstances or the crime, bite mark evidence can contribute an integral part of the forensic investigation.

Animal Bites versus Human Bites

The Centers for Disease Control reports that more than 4 million dog bites occur every year in the United States (Sacks, 1996). Treatment for nearly 368,000 bitten victims occurs annually under the supervision of nurses in urgent care facilities and emergency departments (MMWR, 2003). At first glance, animal and human bites can appear similar, but a closer evaluation will reveal some fundamental differences in their appearance.

Bite characteristics

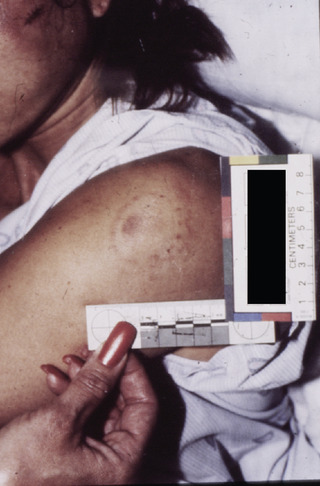

The prototypical human bite is generally an ovoid or circular bruise pattern that consists of two opposing U-shaped arches separated at their bases by open space (Fig. 26-1). Frequently there is a central area of ecchymosis or contusion between the opposing arches (Fig. 26-2). In many bite marks, individual tooth patterns or the dental signaturedental signature left by the anterior teeth can be seen. If the injury meets these criteria, chances are excellent that it is, in fact, a bite mark. Many factors affect bite mark dynamics and appearance, with both the victim and the biter. Age and race of the victim play an important role in the variation of wound healing and visibility of bites (Wilkes, 1973). The location of the bite will affect its manifestation. Bite marks can be distorted due to the biomechanical properties of skin and underlying tissue (Bush, 2009). Bites on unsupported tissue such as the breast usually are more diffused than bites on tissue that is well supported by muscle or bone. Thin skin such as one finds on the face will generally produce more classic characteristics and individualizing characteristics of the biter’s teeth than the thick skin found on the palms and soles of feet. The actual size of the bite mark will vary with the type of tissue and area where sustained. Unsupported tissue typically produces larger-than-life–sized bite marks. Thin, supported tissue generally produces bite marks smaller in size than the actual dentition that created it.

|

| Fig. 26-1 |

Factors linked with the perpetrator include the number of teeth, the strength of the biter, and movement during the act of biting. Bites made through clothing sometimes may result in a diffused bruise pattern. Additional variables to consider are time elapsed before the bite is documented and environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and contamination.

It must be said at this point that there are other blunt force injuries from a variety of instruments that can mimic the appearance of a bite mark; however, this chapter only shows examples of known bites. Ultimately the final determination should be made using the assistance of a qualified forensic odontologist.

Dog bites vary in degree of severity and can be more oblong and even V-shaped. In their least aggressive form, they can appear as a superficial bruise (Fig. 26-3). Similarly, human bites seen and analyzed are often limited to damage of the surface epithelium, dermis, and muscle tissue; or they can appear to be only superficial or predominantly contusions and abrasions. In contrast, the more severe dog bites typically involve punctures and laceration of the skin. Figure 26-4 shows an adult male who was fatally attacked by eight pit bull terriers. Even though there were numerous punctures and lacerations noted at autopsy, the cause of death was asphyxiation, not exsanguination.

|

| Fig. 26-3 |

The most noticeable difference between animal and human bites occurs as a result of the canine teeth. An examination of canine teeth in most domestic animals reveals that they are proportionally much longer, relative to the other anterior teeth, than are human canines to their adjacent anterior teeth. Figure 26-5 demonstrates the obvious size difference between the canines and anterior incisors in domestic dogs. Similar conditions exist in cougars, bears, and many other animals known to have bitten people. As the longest teeth, the canines create the most damage to the bitten victim. Animal canines typically produce telltale punctures and parallel linear abrasions or lacerations caused by movement of these teeth over the surface of the tissue as the bite occurs. Human canines, also typically the longest of the anterior teeth, do not usually inflict the same extent of damage or leave the same pattern as animal canines.

Both animal bites and human bites can take place either as single or multiple injuries. Some lacerations can be fatal, particularly in areas where large vessels are near the surface of the skin, such as in the neck. The crushing power of even a medium-sized dog’s jaws has also been documented to cause multiple fractures in infant skulls and adult bones as well.

Whatever the severity of the bite, in any emergency department setting, concern for the patient is most important and preempts collection of the bite mark evidence. Only after the victim is stabilized and out of danger is attention to be directed to collecting evidence from the bite mark injury.

Pathogenic considerations

The most critical determinant for any animal bite, wild or domestic, is the possibility of rabies transmission. Although studies on maternal periparturient grooming and in licking wounds have shown dog saliva to have bactericidal effects against certain pathogens ( Escherichia coli and Streptococcus canis) (Hart & Powell, 1990), other research has shown canine salivary bacterial content to often contain levels of Pasturella multocida and Staphylococcus aureus, both known human pathogens (Bailie, Stowe, & Schmitt, 1978). In any event, particularly deep bites contaminated by animal saliva frequently require antibiotic therapy (Peeples, Boswick, & Scott, 1980).

The human oral environment can support more than 250 known gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria as well as viral components at any particular time (Leon Levy Center for Oral Health Research 2002). A bite by a human is a much more serious injury than an animal bite from an infective standpoint. Likelihood of infection is virtually guaranteed if penetration of the skin has occurred and was left untreated. In the hospital emergency department or trauma care facility, after DNA sample collection and photographic documentation of a human bite have been completed, thorough cleansing of the wound with a professional-grade antimicrobial detergent should be performed and antibiotic therapy should be initiated. Suturing is typically unnecessary in the majority of human bites, but the opposite is true in animal bites and in the most severe human bites. If left untreated, a penetrative bite to the hand or foot will often ultimately require surgical debridement, parenteral and oral antibiotics, and continued monitoring for cessation of infection.

Bite Mark Recognition

For a bite mark to be recognized as a bite, the injury should first meet the criteria previously mentioned that establish its validity as a bite pattern injury. Occasionally only a single arch is represented, such as in the case of a bite to a finger, hand, or foot (Fig. 26-6). If a nurse examiner is unsure whether or not an injury is in fact a bite mark, the assistance of a qualified forensic odontologist should be requested.

|

| Fig. 26-6 |

Within the classic bite pattern are individual “tooth prints” generally created by the incisal or cutting edges of the six upper and six lower front teeth. Characteristics that may be used to individualize the dental signature to a particular suspect, or rule out others, are most important. Positional relationships of adjacent teeth, rotations, chips and fractures, spacing, and relative height in the dental plane of occlusion are all features that assist the forensic odontologist in the analysis of the bite mark. Some terms generally used to describe the extent of a bite mark injury are petechial hemorrhage, abrasion, contusion, erythema, ecchymosis, indentation, and laceration.

The size, shape, and appearance of a bite mark injury may vary according to the location on the body, skin support, and dynamics of motion during the act of biting. Bite mark analysis is based primarily on correlation of the bruise pattern to the arrangement of the teeth that caused the injury, giving less weight to the relative size of the injury to the teeth.

Types of Human Bites

Two-dimensional bite

A two-dimensional bite is the predominant type of injury that occurs during confrontational episodes. The typical two-dimensional bite has width and breadth but no penetration of the epidermis (see Figs. 26-1 and 26-2). Although one might misconstrue the pressure necessary to create such an injury to be minimal, usually the forces associated with the average human bite are significant and exceed normal pain threshold tolerances. The degree of subsequent bruising depends on a combination of factors, such as the age of the victim, elasticity of the skin, location of the bite including underlying structures, force applied, and morphology of the dentition.

Three-dimensional bite

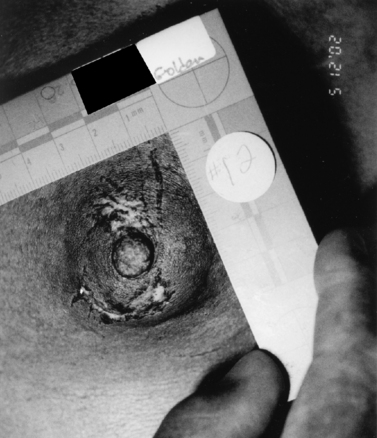

A three-dimensional bite has all the components of the two-dimensional bite plus depth of penetration (Fig. 26-7). When appropriate and useful as evidence, and when the skin surface has been broken during the act of biting, a reproduction of the injury may be obtained utilizing impression materials common to dentistry (Fig. 26-8). The impression should be taken by trained personnel and should be collected soon after the injury and before any long-term healing response occurs. The subsequent imprint of the damaged skin surface can then be used to create either a flexible or hard model of the injury that accurately represents the actual dimensions and depth of the bite. The replica of the injury may then be employed for comparison to suspects’ teeth and later introduced as evidence or used as an exemplar in court.

Avulsed bite

An avulsed bite is one that is so severe in force that the bitten tissue has been completely separated from the victim. Generally, avulsed bites result more frequently from large animals, although in rare instances humans have produced avulsed bites (Fig. 26-9). The avulsed bite is rarely useful as evidence because the actual dental information is lost in the process of forcible tissue removal. If recovered, the piece of tissue might be reattached surgically, but typically, no dental information exists after the suturing or surgical repair. For those people who are unfortunate enough to not survive an attack by animals such as bears, large cats and dogs, and sharks, supplementary information is usually available to confirm the source of the victim’s demise. On some occasions, measurements of the teeth will be taken and DNA samples collected if a suspected animal is located so that a comparison for consistency can be made to the bite mark pattern injuries.

|

| Fig. 26-9 (Photo courtesy Colton Police Department, Colton, California.) |

Bite Mark Analysis

A comparison of a suspect’s teeth to the dental signature left on the skin of the victim can be accomplished by a variety of methods. For several decades, the accepted protocol has included using transparent acetate overlays that indicate the biting edges of the six maxillary and six mandibular anterior teeth (Fig. 26-10). A 1-to-1 (life-sized) photographic print is then created from either a slide, negative, or digital image. The overlay created from the biting edges of the suspect’s teeth is then compared to the pattern injury for consistent features or concordant points (Fig. 26-11). Some odontologists prefer to work at even larger magnifications such as 2-to-1 or even a 3-to-1 for better visualization.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access