Section Twenty-Five Miscellaneous Procedures

PROCEDURE 186 Drug and Alcohol Specimen Collection

PROCEDURE 187 Preservation of Evidence

PROCEDURE 188 Sexual Assault Examination

PROCEDURE 189 Collection of Bite Mark Evidence

PROCEDURE 190 Application of Restraints

PROCEDURE 191 Preparing and Restraining Children for Procedures

PROCEDURE 193 Preparation for Interfacility Ground or Air Transport

PROCEDURE 186 Drug and Alcohol Specimen Collection

INDICATIONS

1. To identify whether the patient is intoxicated by a drug or alcohol

2. To obtain evidence in a criminal case

3. As required by an employer for job-related injuries

4. To obtain laboratory data for a differential diagnosis for an altered mental status or specific signs and symptoms, such as the following (Ohio Chapter of the International Association of Forensic Nurses, 2002; Kerrigan & Goldberger, 2006):

5. To help determine a cause of death and the manner of a patient’s death

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND CAUTIONS

1. Life-threatening conditions should be managed before evidence collection.

2. Blood or body fluid specimen collection for evidence in an alleged crime generally requires patient consent or a court order. Each emergency department should have protocols that govern the collection of blood and/or urine for alcohol and drug screening. Some states have laws or regulations that stipulate that specimens can be obtained without the patient’s consent in specified circumstances, such as a motor vehicle crash resulting in serious injury or death.

3. Collection of blood/urine for alcohol or drug screening for an alleged crime without patient permission may be considered assault and battery.

4. If the patient is exhibiting altered mental status, always rule out organic causes for the patient’s behavior, signs, and symptoms. Hypoglycemia, shock, traumatic brain injury, and drug interactions are only a few of the conditions that can cause signs and symptoms similar to those of drug and alcohol intoxication.

EQUIPMENT

Most states have a specific kit that is used for the collection of blood/urine for legal purposes (Figure 186-1). These kits may be stored in the emergency department or supplied by the law enforcement agency requesting the test.

PATIENT PREPARATION

1. If not covered by state law/regulation or court order, obtain patient consent according to institutional policy.

2. Ensure that the law-enforcement agency requesting the test has explained the procedure and the patient’s rights before the blood or urine is collected.

3. The law enforcement officer should witness the collection of the specimens whenever possible.

4. For all specimen collection, in order to ensure evidence security use the four Ws (Kerrigan & Goldberger, 2006):

PROCEDURAL STEPS

3. Follow and document chain of custody procedures carefully.

4. Blood and urine may require refrigeration if they are not immediately transported by law enforcement or taken to the laboratory.

5. If the specimen must be sent to a laboratory, the laboratory should provide directions for packaging, chain-of-custody maintenance, temperature control, and shipment.

6. Provide the toxicologist with information concerning the suspected drugs, the time the drugs were ingested, how they were ingested, and if the patient has been given any medications in the emergency department.

COMPLICATIONS

1. If only legal specimens are requested and no medical screening examination is performed, the patient may not be appropriately evaluated and could suffer serious injury or even death.

2. If the specimens are not appropriately collected and handled, they may be considered contaminated and ruled inadmissible.

3. If the chain of custody is not preserved and documented, the evidence may be ruled inadmissible.

PATIENT TEACHING

1. Provide the patient with information related to the law enforcement agency that requested the specimens for follow up regarding legal procedures.

2. Instruct the patient/family when to return to the emergency department or call 911 for problems related to alcohol or drug intoxication.

3. Refer the patient/family to the appropriate agency for substance abuse counseling as indicated.

Kerrigan S., Goldberger B.A. Forensic toxicology. In: Lynch V., ed. Forensic Nursing. St Louis: Mosby; 2006:123–139.

International Association of Forensic Nurses. Ohio Chapter of the International Association of Forensic Nurses. The Ohio Adolescent and Adult Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner Training Manual, 2002. Columbus: Author

PROCEDURE 187 Preservation of Evidence

Evidence is something legally submitted to a court of law as a means of determining the truth related to an alleged crime (Doyle, 2001). The sources of evidence are the victim, the suspect, and the scene of the crime (Burgess, 2000). The patient’s body, hospital supplies used to care for the patient, documentation, and the emergency department itself can be sources of evidence in a criminal investigation (Saferstein, 2006). Every emergency department should have a protocol for evidence collection and preservation. The most common types of evidence collected include clothing; bullets; hairs; fibers; blood stains; fragments of materials, such as paint, glass, and wood; dirt; or plants.

INDICATIONS

1. To properly preserve, document, and maintain the chain of custody for evidence that has been collected from the victim of an alleged crime or a suspected perpetrator. Evidence should be collected for (Lynch, 1995; Saferstein, 2006):

2. To properly store evidence so that it may not be altered.

3. See specific procedures on collection of evidence for drug and alcohol testing (Procedure 186), sexual assaults (Procedure 188), and bite marks (Procedure 189).

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND CAUTIONS

1. Medical interventions may destroy evidence. Emergency care providers should recognize and preserve evidence whenever possible. For example, placing paper bags over the hands of gunshot victim can help preserve trace evidence of gunpowder and identify whether it is a self-inflicted wound (Figure 187-1). Also, try not to cut through bullet or knife holes in clothing.

2. Some evidence may be misinterpreted or assumptions made that an injury is self-inflicted. The role of the emergency care provider is one of observation, collection, labeling, storing, and maintaining chain of custody, not interpretation (Lynch, 1995). For example, do not describe bullet wounds as per your interpretation of “entrance” and “exit.” Instead, limit your documentation to objective information, such as wound location, size, and appearance.

3. In order to ensure good evidence collection, emergency care providers should possess accurate knowledge about what may or may not be evidence. Emergency departments should have protocols that indicate when evidence should be collected.

4. If photographic evidence is being collected, photographs should be taken before any treatment, whenever possible. A consent form must be obtained prior to taking evidentary photographs. When the patient is unable to give consent, parents, guardians, or other representatives of the patient may provide consent (Saferstein, 2006).

5. All evidence must be properly collected, identified, and stored. The chain of custody must be maintained or the evidence may not be admissible in a court of law.

6. Do not handle bullets with forceps, because scratches on the bullet may interfere with ballistics analysis.

EQUIPMENT

Evidence collection kit (Kits are available for specific crimes, such as sexual assault or driving under the influence of alcohol. See Procedures 186 and 188 for specific information.)

Suitable containers and sample contents if an evidence collection kit is not available (Containers need to be puncture resistant or tamper evident and prevent exposure to blood and body fluids.)

Evidence tape (provides tamper-evident seal)

Camera and film (instant camera with close-up capability or high-resolution digital camera)

Locked box or area where evidence can be stored until law enforcement assumes custody

PROCEDURAL STEPS

1. Identify the indication for evidence collection and consult with law enforcement if you have any questions about what to collect. DNA profiling can be performed on saliva, bone, soft tissue, hair with roots, nasal secretions, blood or blood stains, semen or semen stains, vaginal secretions, skin and sweat, vomit, feces, and properly stored urine (Doyle, 2001).

2. Obtain the appropriate evidence collection kit (e.g., sexual assault kit) (see Procedure 188).

3. Obtain patient consent for evidence collection according to institutional policy. Note that in some cases, such as homicide or suicide, consent may not be required from the patient for evidence collection. Refer to your state laws and regulations.

4. Check the patient’s clothing for the following and collect clothing as appropriate. If in doubt, collect the item.

5. Change gloves often to prevent cross contamination (Ohio Chapter of the International Association of Forensic Nurses, 2002).

6. Do not perform wound care until injuries have been photographed.

7. Place all collected evidence in appropriate, separate containers. Each article of clothing should be placed in an individual bag or envelope. Avoid placing evidence from multiple victims on the same surface to prevent accidental transfer of vital evidence.

8. Wet evidence should always be dried before packaging. Evidence should always be placed in a paper bag. If you need to submit blood-soaked clothing, place the paper bags in open plastic bags to prevent exposure toblood and fluids. Notify the receiving law enforcement officer that it should be removed from the plastic and allowed to dry in a secure evidence room as soon as possible.

10. Evidence should be sealed with evidence tape. Never lick envelopes or use staples. Licking envelopes may contaminate the evidence with your saliva and DNA.

11. A professional forensic photographer is preferred for evidentiary photography. However, photographs taken by emergency nurses are often helpful.

12. Document the evidence collection procedure. A checklist may useful to ensure that all of the steps have been correctly followed (Johnson, 2003). Document any interventions that may have interfered with evidence collection, for example, cutting off clothing.

13. Place evidence in a locked, secured area. Maintain chain of custody and only release the evidence to the appropriate law enforcement agency.

14. Notify the appropriate law enforcement agency per institutional protocols.

15. Complete the chart and ensure that all pertinent documentation is completed, including a list of what was given to the law enforcement agency, the name of the receiving officer, and the date and time that the evidence was released.

AGE-SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS

1. For every infant death, all clothing, including soiled diapers, should be saved for the medical examiner.

2. Consider abuse or neglect as a cause of a child’s or elderly patient’s injury, and collect and document evidence.

3. There are conditions that mimic abuse and/or neglect and these must be carefully differentiated when examining a patient to avoid false accusations. For example, coining—which may be performed to relieve pain—can leave marks that may be misconstrued for patterned bruising (LaSala & Lynch, 2006).

Burgess A. Violence through a forensic lens. King of Prussia, PA: Nursing Spectrum, 2000.

Doyle, J. S. (2001). Evidence collection handbook from the Kentucky State Police. Retrieved October 8, 2006, from www.firearmsID.com, last updated 2005

Johnson M. Child sexual abuse. In: Thomas D., Bernardo L., Herman B. Core curriculum for pediatric emergency nursing. Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2003:585–592.

LaSala K.B, Lynch V. Child abuse and neglect. In: Lynch V, ed. Forensic nursing. St Louis: Mosby; 2006:249–270.

Lynch V. Clinical forensic nursing. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America. 1995;7:489–507.

Chapter of the International Association of Forensic Nurses. Ohio Chapter of the International Association of Forensic Nurses. The Ohio adolescent and adult sexual assault nurse examiner training manual, 2002. Columbus, Ohio: Author

Saferstein R. Evidence collection and preservation. In: Lynch V., ed. Forensic nursing. St Louis: Mosby; 2006:101–122.

PROCEDURE 188 Sexual Assault Examination

INDICATIONS

1. To provide the physical and psychosocial assessment and management for the survivor of sexual assault (ENA, 2007)

2. To provide nonjudgmental documentation of the history of the crime

3. To collect, preserve, and document forensic evidence

4. To prevent some of the physical and psychological health risks that may be associated with the sexual assault

5. To prepare documentation so that expert testimony can be given in a court of law

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND CAUTIONS

1. Consult state laws and regulations. In some states, sexual assault is a felony and must be reported to law enforcement authorities even if the victim decides she/he is not interested in talking to the police. Also, some states have procedures that allow evidence to be collected and held anonymously by the state crime laboratory for a period of time while the victim decides whether or not to report the assault.

2. Improper interventions may destroy or alter potential evidence. If sexual assault is suspected, every effort should be made to collect according to local law enforcement requirements.

3. Improper or incomplete evidence collection, preservation, and documentation may result in evidence that is inadmissible in a court of law. Survivors of sexual assault are best served by a sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) (Ledray, 2006; Ledray, Faugno, & Speck, 1997). SANEs are specially trained in evidence collection and management as well as in documentation and testimony related to sexual assault. Employment of SANEs in emergency departments is highly recommended (ENA, 2007).

4. Survivors of sexual assault should be triaged as emergent and taken to a private area for assessment as soon as they present to the emergency department.

5. Emergency care providers should receive additional training approved by the International Association of Forensic Nurses (IAFN) before performing pediatric sexual assault examinations (ENA, 2007; IAFN, 2002).

6. Research has demonstrated that the standardized collection of evidence contributes to easier identification of the perpetrator, improved testimony in court, and eventual conviction. Each state has its own legal definitions of sexual assault, and evidence should be collected according to state protocol. State protocols should comply with IAFN guidelines (U.S. Department of Justice, 2004).

7. See Procedure 186 and your local laboratory/crime lab procedures if testing for “date rape” or other drugs is indicated.

EQUIPMENT

PATIENT PREPARATION

1. Perform a primary and secondary assessment to identify any life-threatening injuries that must be managed before evidence collection can begin. In critical situations, the forensic evidence may need to be collected in the operating room or critical care unit. A protocol should be developed and approved jointly by the medical and SANE staff for the management of these patients.

2. Explain the procedures to the patient and have the victim sign the consent forms for evidence collection and photographs. Also have the victim sign consent for release of evidence to law enforcement.

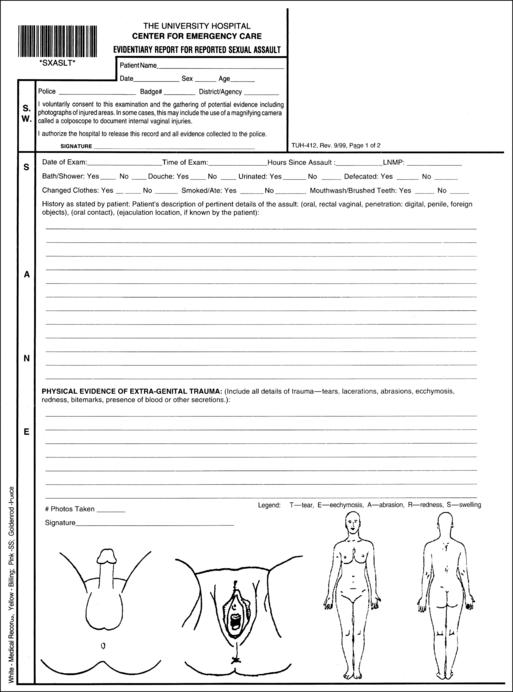

3. The sexual assault examination should be carried out in a private area. Many emergency departments have specific rooms used only for sexual assault patients (Figure 188-1). A patient advocate should be called to talk to the survivor. Some patients may request that a family member or friend accompany them during the examination. The patient’s request should be honored to encourage their attempts to regain control.

PROCEDURAL STEPS

1. Document the history of the assault using a standard form (Figure 188-2). If the patient has showered or changed clothing since the assault, document this and collect evidence regardless. It is suggested that the history be taken with law enforcement present if they have not already interviewed the patient to decrease the need to repeat the history of the assault multiple times. Take pictures of obvious injury at this time. Also take an orientation picture of the victim at this time. Label all pictures per protocol.

2. Unfold the paper sheet on the floor and have the patient remove all clothing. Be sure to give the patient a gown for cover and have her/him sit on the stretcher. At this time, observe the victim for signs of injury, such as bruising, bleeding, swelling, redness, or bite marks. Collect all pertinent clothing worn during or immediately after the assault. Do not shake the clothing, and place each item in a separate paper bag. Seal with evidence tape.

3. Collect oral swabs regardless of the history given. Make a smear with a swab on a slide. Allow the swabs to air dry or place in a swab dryer. When the swab is dry, place it in an envelope and seal with evidence tape.

4. Collect hair standards. Allow the patient to pull 10 to 15 strands of hair from various spots on the head with gloved hands. Place the hairs in an envelope, seal with evidence tape, and label. (Protocols vary and may allow cutting or pulling hairs).

5. Scrape/swab under the patient’s fingernails. If there are broken nails, cut a piece of the nail and place in the envelope, seal with evidence tape, and label.

6. Scan the patient’s body with the Wood’s lamp to identify any dried semen or saliva stains. Different fluids fluoresce under black light. Any areas that fluoresce should be swabbed. If the area is dry, use a moistened swab (water or saline) to sample. If the area if moist, use a dry swab. Air dry the swabs and place them in an envelope, seal with evidence tape, and label. Swab injured areas only after a photograph has been taken.

7. Place the patient in the lithotomy position. Comb through the patient’s pubic hair several times with an envelope or a paper towel under the patient’s buttocks. If there is an area of matted hair, cut the area out with scissorsand place it in the envelope. Place comb in the envelope with the hair. Seal with evidence tape and label. If there is no pubic hair, document that on the envelope.

8. With a gloved hand, the patient should pull 10 to 15 stands of pubic hair. Place these in an envelope, seal with evidence tape, and label. Refer to your state protocol for the required amount.

9. *For female patients: Inspect the genital area, photograph all injuries, and explain the speculum examination. Colposcopic photography may be performed at this time. Insert the speculum (plastic is recommended to provide better photography). Collect four swabs from the vaginal vault and cervix. Collect any foreign objects. If a tampon/pad is present, collect, dry, and seal in the kit. Make a slide from one of the swabs, dry, and seal in a labeled envelope. Allow the speculum to air dry and place in the evidence envelope.

10. *For male patients: Inspect the genital area, and photograph all injuries using the colposcope. Moisten four swabs with saline or water. Swab the glans and shaft of the penis. Make a slide, dry, and place in the labeled evidence envelopes.

11. *Examine the anal area for injury, and photograph all injuries. Collect four anal swabs regardless of the assault history. Make a smear with one of the swabs on a slide. Place this swab in a labeled evidence envelope.

12. Collect blood standard on filter paper provided in the kit. Wear gloves, label the filter paper, wipe patient’s finger with alcohol, perform a fingerstick, and place a drop of blood on each circle. Dry and place in the envelope. Alternatively, some jurisdictions require a tube of blood be drawn from the patient.

13. *Complete the assault history form (see Figure 188-2) documenting sites of injury and your findings during the examination. One set of photographs should be given to law enforcement with the kit. One set of photographs should be kept with the medical record.

14. Administer sexually transmitted infection (STI) prophylaxis and pregnancy prophylaxis as prescribed and indicated. Explain to the patient about the need for follow up with these treatments.

15. Make sure that all evidence is sealed correctly and that your documentation is completed according to protocol. The sealed completed kit and documentation should be immediately surrendered to a law enforcement officer to maintain chain of custody. If you are unable to give your kit to law enforcement immediately, a locked, secured cabinet should be available for storage until law enforcement retrieves the kit. It is critical to maintain the chain of custody with all evidence and documentation.

COMPLICATIONS

1. The patient may decline specific parts of the sexual assault examination. Document “the patient declines” as indicated.

2. Improper collection or handling of the evidence or a break in the chain of custody could cause the evidence to be inadmissible in a court of law.

3. Patients may experience nausea and vomiting from the STI and/or pregnancy prophylaxis. Discuss this with the patient and offer suggestions for successful completion of the medication regimen. Written discharge instructions should be given to the victim so that the victim or a family member can review it at a later time. Because of the traumatic circumstances of the assault, victims may not comprehend the instructions at the time of discharge. Provide a phone number for any follow-up questions.

4. STI and pregnancy prophylaxis may not be effective. It is imperative that the patient be instructed about follow-up care.

5. Male survivors of sexual assault tend to suffer more physical injuries and should be carefully examined so a life-threatening injury is not missed (Burgess, 2000).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree