CHAPTER 25. Blunt, Sharp, and Firearm Injuries

Patrick E. Besant-Matthews

The forensic nurse examiner must thoroughly understand the multiple characteristics of blunt and sharp force injuries or wounds and be able to predict the types of mechanical forces that might have caused them. This includes, in some cases, a specific weapon or wounding instrument. To make accurate annotations in the medical records or to convey pertinent information to members of law enforcement or the judicial system, it is essential that precise, nonambiguous descriptive terms are used in both oral and written communications. In addition, for known or potential forensic cases, photodocumentation is a vital element to record the size, location, and nature of blunt or sharp force injuries. The ability to relate this information to accident or crime scene reconstruction can assist in the identification of the wounding instrument and eventually the perpetrator.

This chapter introduces wound identification, classification, and documentation by focusing on the details that will contribute to appropriate medical care and later to a credible forensic investigation.

Wound Terminology

In the English language, many words have multiple meanings, which gives rise to the misuse of words, even common ones. A good example is the word fire, which has at least nine common meanings:

1. The phenomenon of combustion manifested in heat and light

2. To inspire a person

3. Liveliness of imagination

4. Brilliancy, luminosity

5. To discharge or let off

6. To discharge from a position, dismiss from employment

7. To process by applying heat

8. To fuel or tend a boiler or furnace

9. To eject or launch a projectile

Almost any large, unabridged dictionary will list several other less common meanings.

In the healthcare and law enforcement fields, doctors, nurses, paramedics, emergency medical technicians, and police officers devote considerable time during training to mastering necessary technical phrases. Failure to continue this education into description of injury often reduces the quality of documentation, even though reports may be lengthy. The surgeon’s report after an operation may contain numerous statements about an injury and what was done to it, yet this report often fails to specify where on the body surface the wound was located or to include other characteristics such as its size and appearance, which may be of great importance when a lawsuit is filed.

Anyone working in the medical or law enforcement fields may be called on to interpret injury patterns; to write reports concerning the condition of someone, dead or alive; and sometimes to testify concerning the appearance of an injured party. Proper use of descriptive terms greatly enhances one’s ability to write effective reports and to provide meaningful information in depositions or testimony. This also applies to day-to-day progress notes. Skill and effort are wasted if descriptions are not absolutely clear and meaningful.

Documenting wound characteristics

A common failing of treatment and surgical reports is that they do not mention the specific place, depth, and direction of force related to the identified injuries. After a critical surgery, the location of wounds should be included in the dictated report. For example, in the case of a single stab wound, failure to note that it entered the abdomen at a point located about 3 inches diagonally above and to the patient’s right of the umbilicus, penetrated for a maximum depth of about 3 inches, and was directed from front to back and slightly downward is a significant omission. What was injured and repaired will almost always be mentioned, but without a location this information will not be much use. Courtroom questions are inevitably centered on the location, depth, and direction, because these are the features that will fit or discredit the allegations and circumstances.

Body Diagrams

Outline diagrams of the human body and body parts can be useful. Simply draw the findings on these outlines and add notations. It is fast, accurate, helps to prevent right/left errors, and makes it easier to document angles and patterns. Body diagrams are excellent supplements to other documentation.

Clock Face Orientation

The clock face is sometimes used to document the angulation or inclination of a feature or wound. For instance, if a person is standing at attention (in the standard anatomical position) and has a streak of dirty material running from the inner part of the left eyebrow to the lower right corner of the mouth, then this might be described as being oriented from 1 to 7 o’clock when viewed from the front. If the standard anatomical position is not used, additional documentation is needed, such as “when viewed from the right, with the patient lying face up, the wound is angled from 10 to 4 o’clock.”

Track and Tract

A track (spelled with a “k”) is detectable evidence that something has passed, a vestige or trace, or the course along which something has moved. Note that the word tracks is also used to describe the linear scars overlying veins resulting from repeated intravenous injections associated with drug abuse.

A tract (spelled with a “t”) is a series of bodily parts that collectively serve a combined anatomical purpose. There are more than 50 tracts within the body.

So unless someone swallows or inhales a bullet, it will pass down a track, not a tract. Failure to distinguish between track and tract is a reliable indicator of the amount and quality of training received, as well as the care, or lack of it, in producing reports.

Instrument and Weapon

An instrument is something with, or through which, something is done or effected (i.e., a tool, implement, or utensil). Namely, it is an object with a primary function other than use as an offensive or defensive weapon. A weapon is an instrument of offensive or defensive combat, something to fight with, or an object of any kind used in combat to attack or overcome others. A weapon is essentially an object whose primary function is as an offensive or defensive device. An object such as a kitchen knife, although manufactured as an instrument, can be used as a weapon. Proper use of these terms will depend on the circumstances and fashion of use (e.g., to cut bread or to cause injury).

In this chapter there are many of the terms used to describe injuries. It is suggested that anyone who treats patients, evaluates injuries, or works in the fields of law or law enforcement be exposed to and be aware of these terms, not only for personal benefit but also to protect the interests of the institutions and individuals they serve.

Forensic nurse examiners may be requested to testify or to give a deposition; therefore, it is important to use appropriate and precise terms when describing injuries or wounds in forensic cases. The failure of a report to be completely accurate may cast doubt on one’s credibility as a witness or testifying expert.

Documentation and legal proceedings

An injury that is of little consequence medically may be extremely important to family members, investigators, insurance companies, attorneys, and the courts. For example, suppose there’s an L-shape abrasion (graze), about 11/4-inches in greatest dimension, on the inner aspect of the left lower leg near the bony prominence of the ankle joint. The wound is reported to be the result of an automobile collision, is not life threatening, and will soon heal. Later it turns out that both occupants of the vehicle are unconscious, the brake pedal is bent, and the main issue is determining who was driving. If the leg is in a cast, and nothing was noted in the chart, the wrong person may be charged with negligent driving, manslaughter, or even vehicular homicide.

There are several routes to good documentation. Here are some points to ponder:

• Describe wounds in logical sequence, such as from head to foot, or from front to back, or from wrist to elbow. Organization is important in court.

• Use landmarks that cannot easily be challenged by a skilled attorney. Good landmarks include the midline of the body, the notch at the top of the breastbone, the centerline of a limb, the base of a heel (provided the ankle is at 90 degrees), the top of the head, the external ear canals, or the Frankfort plane (the horizontal line between the bottom of the eye socket and the top of the external ear canal). The best choice depends on the case and even on the direction of force.

• When dealing with stab wounds (and bullet holes), measure from the body landmark to the center of each. This is important when there are many irregular wounds, or else the distances between them will not add up.

• If measurements are made around a body curvature, make it clear in the description. Failure to do so will cause a wound that’s recorded as 12 cm to the left of the front midline of the face to sound as though it is out in space somewhere, instead of 5 cm in front of the ear canal.

• Do not locate one injury and then say that another was at a certain distance from it. Doing this will accumulate measurement errors. This rule does not apply if injuries are obviously paired (e.g., carving fork) or grouped (e.g., dinner fork).

• Do not split up or disperse parts of a single injury within the notes. If there is no choice but to examine the outside before the inside, then “Subsequent examination of …” will get the narrative back on track.

• When describing marks that encircle or partly encircle the wrists, ankles, or neck, pick a starting point, and begin with “For descriptive purposes, the marking commences at a point,” continue on, until returning to the starting point.

• Use national standard or internationally accepted abbreviations. A common error is to use cc for fluid volumes, when fluids are measured in liters not centimeters. Thus, ml is technically correct. In many important cases, consultants will read the report, note minor errors, and bring them to the attention of the defense.

• If someone misinterpreted a birthmark as a bruise, but injuries were not substantiated, it will help to make notations such as “Not found—evidence of injury to the face” or “Incidental findings—birthmark (“port wine” stain) on face.”

Good forms and a notation system (using arrows and lines with clock face numbers at each end) make notes easier to read during a deposition or courtroom testimony.

Blunt and Sharp Injuries

From a medical perspective, the ability to distinguish between the various types of injuries is extremely important because it provides valuable information about causation and, in some cases, will determine treatment. For example, a confused young female patient is admitted to the emergency department with a linear injury to her upper forehead. If this injury has been caused by a sharp instrument such as a straight razor, there is little to be done except to suture the wound and then explore how it was incurred. Did it occur as an accident? Was it the result of interpersonal violence? Was it self-inflicted? Answers to these questions will be extremely important to the healthcare team and to law enforcement. Perhaps the patient had been drinking or taking drugs? However, if the linear injury was caused by being struck forcefully by the edge of a coffee table or a piece of angle iron, then the clinical problem is quite different and involves wound contamination, blunt force injury, potential for skull fracture, and neck injury, plus the need to consider brain injury with or without intracranial bleeding. Sharp force injury rarely contains trace evidence.

Proceeding appropriately requires distinguishing a sharp injury from a blunt injury. However, these are the two most frequently mistaken for one another in those areas of the body surface that have bone beneath them, including the skull.

The forensic nurse examiner must actively be involved as an investigator when providing wound care in a clinic or within the hospital emergency department. If the wound occurred as an industrial accident (on the job) rather than while the individual was engaged in recreation, workers’ compensation and other insurance coverage may be relevant. If the victim of injury subsequently has extended complications or dies from the wound, there may be issues of liability and criminal negligence. The cause of death or permanent disability also impacts the payment of claims on disability policies or life insurance. If the wound was self-inflicted, there are important mental health implications to explore. If an assailant caused the wound, there is the need for law enforcement to find the perpetrator. Forensic responsibilities cannot be taken lightly because they may make a huge impact on law enforcement, the judicial system, and the overall economy. Taking time to carefully remove clothing, to photograph and measure the wounds, and to precisely document the patient’s statements regarding how the wound was incurred will become extremely important if there are subsequent judicial proceedings.

Symmetry of abrasion, bruising, and undermining of tissue is consistent with a more perpendicular application of force. An example would be on the scalp, over the curved surfaces of the skull, if an individual were struck with the flat surface of a 2-by-6-inch piece of wood. Because lacerations result from blunt impact, shearing, or tearing, they are likely to be contaminated with foreign material such as road gravel and dirt, headlight glass and paint chips, or clothing fibers indicating the kind of surface that was contacted. For example, examination of a traffic accident victim may reveal the presence of small fragments of paint within a tear on the side of the head, indicating that the head contacted part of a vehicle; or it might contain gravel and greasy dirt, which is more in keeping with contact with the underside of a vehicle.

Improper description and interpretation of injuries may lead the police on a lengthy search for a knife or sharpened object when in fact they should be looking for a brick, angle iron, or other such angular object with a definite edge to it. Experience shows that sharp injuries (cuts and stabs) are better understood than blunt injuries (scrapes, bruises, tears, and fractures).

Pattern of injury

A pattern of injury is a combination or distribution of external or internal injuries that suggest a causative mechanism or sequence of events, indicating infliction of wounds over a period of time versus those occurring simultaneously. A pattern of injury may indicate repetitive abuse, whereas injuries occurring from a single incident are generally associated with nonintentional injury.

Pattern injury

A pattern injury is one that possesses features or configuration indicative of the object(s) or surface(s) that produced it (Smock, 2007). For instance, it may bear the imprint of clothing, an object such as the radiator grill of a car, or the head of a specific type of hammer.

Penetrating and perforating

A penetrating injury is one that enters but does not exit, whereas a perforating injury passes through and through. Thus, confusion may arise because a knife that entered the front of a thigh and stopped just short of the bone represents not only a penetrating injury of the thigh as a whole but also a perforating, through-and-through wound of the skin. It is necessary therefore to specify what was or is penetrated or perforated. Use penetration as the common term for the majority of injuries that enter and do not exit, and refer to all others as through-and-through injuries.

Blunt Force Injury

There are four main subdivisions of blunt injury:

1. Scratches and grazes—abrasions

2. Bruises—contusions

3. Tears—lacerations

4. Fractures of bone

These types of injury often occur in combination, but each will be reviewed separately.

Abrasions

An abrasion represents the removal of the outermost layer of the skin by a compressive or sliding force. Usually the skin is not perforated, but this can occur if the force and severity are sufficient or if the injury is great enough for areas to be physically worn away. Abrasions are seldom life threatening, but they are of great importance in interpreting what happened because they must, by their very nature, mark the exact point at which contact occurred (Fig. 25-1). Thus, the presence, form, and distribution of abrasions may need to be recorded in considerable detail. As blunt force is applied to the surface of the body, two vectors of force come into play. One is directed primarily inward and the other primarily longitudinally or parallel to the skin surface. The magnitude of each may differ, producing characteristics that allow subdivision into pressure or sliding types. It is well to consider abrasions in these terms, because it makes one think about the mechanism of injury and direction of force. The surface tissues may be pushed toward one end of a sliding abrasion, like dirt moved to the far end of the “push” by a bulldozer or road grader, in which case tags and tissue fragments frequently indicate the direction toward which the force was applied (Fig. 25-2).

Similar to most wounds, abrasions tend to darken as the tissues dry. In most instances, this is noted first at the edges of the wound or in more shallow areas of the abrasion. After death, when there is no longer circulation or body movement to keep them moist, abrasions will dry and darken. This may lead to the false interpretation that the injury resulted from burning, bruising, or even that a hot object contacted the tissues.

Abrasions are sometimes classified according to their shape. If long and narrow, as from contact with thorns, they are called scratches. If wider areas are involved, they can be called grazes. The claws of a cat will leave scratches. The knee of a child who fell from a tricycle onto blacktop will be described as grazed. The direction of force is useful in evaluating the patient’s statement of how the injury occurred. For instance, are the abrasions due to being struck on the thigh or buttock by the front of a car or due to the victim’s sliding along the road surface after being knocked down? The form and appearance of the injury should be noted because it may help interpret the mechanism and circumstances of injury.

In summary, abrasions have the following characteristics:

• Indicate contact with a rough surface or object

• Indicate the exact site of contact or impact

• Will eventually crust over or scab (i.e., dry and darken)

• May reveal the direction of the force of injury

• May exhibit characteristic patterns (e.g., knurled tool handles, motorcycle drive chains)

• May be seen in conjunction with bruises and lacerations because forces sufficient to produce scraping may distort the underlying soft tissues enough to tear vessels

Contusions

A contusion, or bruise, results from leakage of blood from vessels into the tissues after sufficient force has been applied to distort the soft tissues and tear one or more vessels—hence the term extravasation ( extra = outside; vasa = vessel). The vessels involved are usually small (such as capillaries), but they may be larger and on occasion, when a larger vessel is involved, leakage can occur quite rapidly. An abrasion may be observed nearby, and if present, it may signify the exact point of contact or application of force. Fresh bruises may be slightly raised above the adjacent surfaces if enough blood escapes, and even when a large bruise is deeply seated, swelling may be apparent when the size of a limb or body part is compared to its opposite member.

Contusions result when blunt forces distort the soft tissues to an extent sufficient to result in disruption and leakage of blood vessels. Escape of blood from the blood vessels is what produces the discoloration. The amount of blood that escapes from the vessels will depend on features such as the size of the contusion and the pressure within it, the ability to clot, the space available for blood to leak into, and so on.

The subcategories of contusions include the following:

• Deep seated, such as in the internal organs, often in the form of hematomas

• Beneath the skin, where contusions give the discolorations commonly know as bruises

• In the skin itself, where the contusions give rise to patterned bruises

There are two other meanings of the word contusion, both of which relate to the brain:

1. The clinical meaning of contusion describes a somewhat imprecise clinical diagnosis of a patient who, after a blow to the head, suffers prolonged loss of consciousness with appearance of clinical signs of brain injury. Note that the expression “contusion of the brain” is not typically used in the presence of dramatic and definite clinical signs such as paralysis. In such circumstances, the description becomes “head injury with hemiplegia.”

2. Contusion of the brain substance occurs when forces are exerted on the head, sufficient to cause the crests of the gyri (surface ridges of the brain) to contact the inner surface of the skull. This results, in the early stages, in small linear hemorrhages resembling splinters of wood under a fingernail. These hemorrhages may become larger and more confluent if injury is more severe.

Fresh Bruises and Color of Bruises

A fresh bruise usually begins with the reddish color of oxygenated blood, from the arterial side of the circulation, but like superficial vessels these bruises may appear blue. This is because blue light bounces (e.g., blue light bouncing off dust particles in the atmosphere gives blue skies) and red penetrates more deeply (e.g., restaurants use infrared lights over the food to keep it warm). Also think in terms of varying depths of skin and yellow fat. Later bruises turn a more purplish hue and ultimately, as the blood pigments break down, the sequence of colors passes through those of a ripening banana, through greens, yellows, and browns, at which point the coloration fades. A closed bruise with only a scrape on the skin above it will not behave the same as a bruise forming in distorted or torn fat, or one that can leak out through a defect in the skin.

The persistence of discoloration varies with age, location of the bruising on the body (circulatory efficiency), and the amount of blood released. Some individuals bruise more easily than do others of the same age and sex; others seldom bruise. Bruising can be masked by natural coloration of the overlying skin and may be almost invisible if the skin is heavily tanned or naturally dark. At late stages, long after injury, discoloration may remain. However, this remaining discoloration may well be more of a response to injury (scar formation, breakdown products of blood pigments, and melanin) than true bruising.

Estimating the Age of a Bruise

The rate at which a bruise appears and disappears depends on many factors, including the quantity of blood originally released, the effectiveness of the local circulation, age, location of the bruised area on the body, and the general physical activity and condition of the individual. Some textbooks and journal articles suggest the rate at which bruises fade is fairly predictable; however, the various authors disagree on the rate. Any opinion concerning the age of a bruise based on its color is extremely difficult and should be attained and stated with the greatest caution and circumspection (Smock, 2007).

Estimating the age of bruises based on appearance or coloration is difficult, both before and after death. To prove the difficulty during life, simply observe bruises of known age. In postmortem tissues, age estimation is difficult with both the unaided eye and the microscope. The pathologist should obtain a set of tissue sections to ensure a truly average and representative sampling. During testimony, it is prudent to admit that there is every reason to be both cautious and skeptical when trying to match changes in injured soft tissues in a person who may have been in shock and organ failure or undergone treatment (including advanced life support, transfusions, antibiotics, and dialysis), and then try to draw a parallel with results from studies in humans and experimental animals taken in the days before modern-day techniques were even thought of.

The forensic nurse examiner should make detailed annotations about the size and appearance of the bruise rather than attempt to estimate the age of the bruise based on literature. Photographs of bruises taken immediately upon examination are also helpful as a means of documentation because the characteristics of the affected area change gradually over hours and days.

Distribution of Bruises

The distribution of bruises may be important. Small bruises around the neck or on a limb may be the only external signs of violence. Indeed, it is possible to have massive internal injury with very little evidence on the body surface, and on occasion there may be no evidence whatsoever. Sometimes superficial patterned bruising may be of value in identifying a particular instrument or weapon such as a whip or cane in which the bruises may have a linear or double-line configuration. When called on to examine the victim of an alleged assault, remember that bruises may not become visible immediately and therefore may not be visible at the time of an examination performed soon after the event. Advances in technology using alternate light sources aid in detecting bruised tissue, even before the skin reveals any type of discoloration. Later on, even without special adjuncts, bruises are likely to become visible on the body surfaces. Reexamination of a victim, updated annotations in the medical record, and careful photodocumentation may provide helpful comparisons with the original observations. This is particularly true with cases of alleged abuse of an elderly person in a nursing home. Bruising may be found in the areas around the eyes and within the soft tissue of the eyelids themselves, particularly in the elderly who sustain minor impacts to these regions when they collapse or fall. Discolorations do not necessarily appear at the place(s) at which force was applied because the coloration may result from blood that has tracked around muscles and flowed in the tissue fluids on route to the surface. For example, hitting the ankle sometimes results in discoloration of the toes. Only an abrasion or a pattern in or near the bruising itself will indicate the actual point of contact.

Bruiselike discoloration can appear many inches away from the point at which force was applied and look just like bruising when it was not involved in the force and remains the same color until it fades. Bruises of many colors are seen simultaneously as a result of a single episode of injury. This should confirm that bruises do not develop at the same speed or progress and resolve in a uniform fashion. In addition, there are cases in which several bruises result from accidents such as a fall or walking into a door. Yet these bruises disappear at different rates, some taking far longer than others. The forensic nurse examiner should consider that one or more bruises of different ages may be adjacent to or overlapping one another, confusing the assessment.

Advanced Assessment Techniques

Because color tends to be an unreliable indicator for the age of the bruise, the forensic pathologist may need to use advanced techniques of tissue study to determine the timing or duration of the injury that caused the bruising. Subspecialists may also be used to provide additional information about certain body tissues such as the heart, brain, or liver. It is imperative, however, that representative tissue samples are obtained and that reference tissues from other body parts are used for comparison, especially when there are complicating factors such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation procedures, blood administration, or the use of mechanical ventilation.

If someone states the exact age of a bruise based on its color, continue to evaluate the case because there is a high probability that the estimate of age will be wrong. Arrests of suspects should not be based on bruise coloration alone but on the result of a comprehensive investigation of all pertinent factors.

Patient Populations with Easy Bruising

Bruising is accentuated in the presence of blood dyscrasias such as leukemia or any impairment of the blood-clotting processes, including hemophilia. Bruising is also commonly noted in patients who are on anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, a class of antidepressants (e.g., Zoloft), inhibit blood platelet activity and may be associated with bruising in unusual locations.

It is generally easier for blood to escape into loose tissues and fat; therefore, bruising is more common in the following circumstances:

• In certain parts of the body

• At the extremes of age

• After weight loss

• In obesity

• If there is disease of the blood vessels

Relationship between Blunt Forces and Bruising

The intensity and duration of forces associated with bruising are difficult or impossible factors to estimate unless other features such as abrasions or lacerations are also present. Significant blunt forces do not necessarily result in the formation of bruises. Not every blow a boxer strikes results in a bruise, and many such blows are forceful. Tissues exposed to repeated trauma may firm up and scar, making it harder for blood to enter and for bruising to occur. The forceful distortion of tissues necessary to result in bruising may itself selectively alter the ability of blood to make its way through injured tissue, such as fat, to the body surface to produce discoloration. If a vessel is lacerated, any blood that escapes will tend to depart through the open wound rather than permeate into the adjacent tissues. Thus, a laceration may have less bruising adjacent to it, not more, even though the force was greater. Likewise, if fat is slightly torn beneath a closed wound, the blood will pass more easily into some parts than others.

In the living, a bruise may appear more or less prominent, according to the amount of peripheral vasoconstriction (standing out in the cold) or vasodilatation (just after a hot bath) of adjacent and overlying skin.

Postmortem Bruising

The question often arises as to whether it is possible to produce bruising at and around the time of death or even after death. Limited bruising can be produced immediately following death if the body is mishandled or struck, assuming enough blood is present and is free to move (not set, sludged, fixed, clotted, or otherwise altered) under the influence of gravity. Therefore, everyone who handles the recently deceased should be cautious.

Postmortem bruises are, however, usually small, few in number, and localized, and they do not usually pose much of a problem. Bruises are easily overlooked in areas into which blood has been forced or has settled (including postmortem lividity) or in areas in which circulation is failing. In some instances of severe injury accompanied by rapidly falling blood pressure, bruises that are still forming at the time circulation ceases may assume colors that are more commonly associated with greater age. These often have a subtle, almost grayish appearance.

After death, it may be necessary to cut into the skin to demonstrate subtle or concealed bruising, especially if there is any significant degree of natural coloration of the overlying skin. In some European countries, where open-casket funerals are relatively rare, it is not uncommon to demonstrate the presence of bruising at autopsy by completely removing selected areas of skin. In the United States, where open-casket funerals are common, only the minimum number of incisions necessary to properly define the nature and extent of bruising are made.

Focal bleeding within the soft tissues of decomposed or decomposing bodies is difficult to interpret, requiring considerable experience on the part of the forensic specialist. Decomposition makes it much harder to tell antemortem from postmortem bruising. Bruising is harder to see in areas of postmortem lividity.

A body (following death from head injuries) was first examined in the autopsy room and had a normal color, normal face, and unswollen eyelids. Photographs that included the face were taken of injuries on the front of the body, and other photos were taken for identification purposes. After the examination of the front was completed, the body was turned facedown for examination, documentation, and photography of injuries on the back. By the time the body was once again turned faceup for opening and internal examination, both upper eyelids had swollen and turned blue-gray from leakage of blood from fractures of the supraorbital plates, the thin bone between the frontal lobes of the brain and eyes. Although uncommon, under the right circumstances, if blood is present and free to move, such effects can and do occur.

Keep these points in mind when assessing bruising:

• Bruises may not become visible for minutes, hours, or even a few days. This is possible because it may take time for blood leaking from vessels located beneath fat or behind other structures such as fascial planes to wend its way to the surface. Furthermore, in the presence of shock, the extravasation of blood may be retarded until adequate perfusion pressure has been restored.

• Bruises are often larger than the area of impact or the causative object because of the flowing and spreading of blood as it makes its way to the body surface (Box 25-1).

Box 25-1

To learn more about the practical aspects of bruising, use 3 × 5-inch file cards or make forms on a computer. Put the following headings on the cards or forms, and fill in the data whenever bruises of exact known age are observed. Be extremely selective, and include only those cases in which the time of injury is absolutely known and is therefore the true time since injury.

• Identifying information, such as hospital, ambulance, or dispatch number

• Date and time of observation

• Ambient/prevailing lighting

• Age, sex, skin color

• Location and size of bruise/bruises

• Bruise color in your own words

• Cause of the injuries and bruising (e.g., motor vehicle collision, bar fight, fall)

• Ambient/prevailing temperature and prior activity (vasoconstriction or vasodilatation)

• Any medications or conditions that would affect the clotting process

Look for injuries that occurred at the same time but that developed different colors (for instance, if someone falls and the bruise on the person’s face is yellow whereas another bruise on the trunk is purple).

Another worthwhile study is to make a note of the date and minute when you accidentally hit yourself hard enough to notice it. If a bruise appears, you will know the time of injury to a minute and be able to record any discolorations that result. If you do not bruise, you will be able to state that when you hurt yourself to the point of discomfort you only get a bruise a certain percentage of the time. Whether you do or do not bruise easily, the results may surprise you.

Ecchymosis

Ecchymosis is a term that is often misused by clinical personnel. Ecchymoses (plural) are not the same as contusions or bruises. They are small, nonelevated, painless hemorrhagic spots that tend to be somewhat larger than petechiae. Typically they are irregular and appear as blue or purplish patches. These ecchymotic spots are induced by bleeding of a hematological nature, not trauma. They are found in both skin and mucous membrane. Capillary fragility in older adults often leads to ecchymotic areas from slight to moderate pressure from an outside force. When described in forensic or medical documentation, they are often termed senile ecchymosis (Fig. 25-3) (Beutler, et al. 2001).

Lacerations or tears

The term laceration is commonly misused when describing injuries. Blunt objects produce lacerations, and sharp objects produce cuts, incisions, or incised wounds (Wright, 2003). A surgeon may make an incision with a surgical knife (scalpel) and call it an incision, then walk into the emergency department, examine a knife cut on a patient’s face, and call it a laceration. This misuse is not only incorrect, but it can also cause confusion with legal implications.

Strictly speaking, lacerations are defects in soft tissues resulting from tearing, ripping, crushing, overstretching, and shearing. Soft tissue defects should be described as tears (lacerations) or cuts (incised wounds) to indicate if an injury was from a blunt or sharp object when a medical record is reviewed.

In the boxing community, a tear near a boxer’s eyebrow is referred to as a cut. The tear in the skin near the eye occurs when the heads of the two boxers collide so that the soft tissues between the bony ridges and surfaces are forced aside. To illustrate, lay a line of toothpaste along the edge of a bathroom sink and then press a finger into it. The paste will escape from either side of one’s finger. So it often is with soft tissues and, to be technically correct, lacerations do not result from sharp objects. Use of the term laceration should be strictly reserved to those wounds that result from blunt force.

Compressive shearing force applied to a tissue or organ may cause an internal tear without external tearing; the impact site in such instances may only be denoted by an abrasion or nearby bruise. Because overstretching of tissue is an important factor in the production of lacerations, the plasticity or potential mobility of the tissues influences the occurrence of this type of blunt injury. Therefore, skin lacerations are frequently found overlying bony prominences of the body where the skin is relatively fixed and less able to move when stressed. Similarly, laceration of the aorta or other organs occurs most frequently at points of relative immobility or mechanical disadvantage, particularly if the energy of impact is conducted to a point at which the vessel or organ is fixed to an adjacent structure.

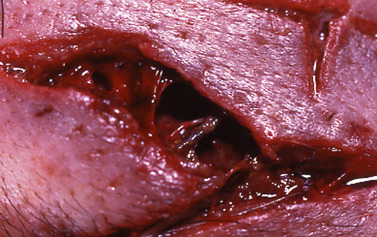

Typical Skin Lacerations

The typical skin laceration has an irregular margin that may be scraped or bruised, especially if there was an impact with an object or rough surface. Because the tissue is torn apart, there is frequently an incomplete separation with stronger tissue elements (such as little blood vessels, nerves, and connective tissue strands) surviving to bridge or span the gap from one part or side of the wound to the other. This bridging of tissue is particularly evident deep within a wound or at its corners and is helpful in accurately differentiating blunt from sharp force injury. Closer inspection of lacerations may reveal characteristics that are useful in interpreting the mechanism of wound production. For example, if one side is scraped/abraded and the opposite margin undermined, partly crushed, or pushed aside, these findings suggest that the force was directed at an angle over the surface, which was scraped and directed toward the side that is crushed, undermined, or pushed back (Figs. 25-4 and 25-5).

Internal Organ Lacerations

Lacerations of internal organs are a relatively common result of blunt force or impact applied to the exterior of the body. Classical injuries involve the liver, spleen, and kidneys, all of which tear with relative ease if the force is sufficient. The lungs may be torn by inwardly displaced ends of broken ribs or result from severe forces. It is noteworthy that it is possible to have serious internal blunt injures without surface manifestations such as abrasions and bruises. If this were not so, surgeons would never have to undertake exploratory procedures to rule out injury. Surface indications are often present, but they do not have to be, and their absence does not rule out the possibility of internal injury. The following list identifies key points to remember when assessing lacerations:

• Lacerations result from blunt force, crushing, tearing, ripping, shearing, overstretching, bending, and pulling apart of soft tissues.

• They have ragged, variably irregular margins.

• They will, in most cases, have scraping and bruising of the wound margins.

• They may bleed less and become infected in crushed tissues (especially if the victim survives).

• Lacerated tissue may survive the force and be observed “bridging” or “spanning” within parts of a wound if it is a stronger tissue component, such as blood vessels, nerves, tendons, and connective elements. Hair roots and other skin structures may be seen protruding from the margins, having been torn out of their supporting tissues.

• They frequently contain foreign materials including trace evidence such as glass, paint chips, bark, fibers, and grease.

• Their overall size and shape vary widely by virtue of their blunt, tearing, shearing, or crushing origin. When attempting to reapproximate the edges of a blunt torn injury, the examiner may notice that the wound still looks ragged, whereas most sharp injuries are more easily restored for suturing.

• Tears resulting from forceful contact with angular objects can, if there is underlying bone, lead to the formation of linear injuries, which may be mistaken for cuts from sharp objects.

• Lacerations may indicate direction of force when, for instance, the bent knee of a vehicle occupant hits the lower part of the dash in a frontal collision. Some people use the expression “trapdoor laceration” to describe the directional nature of such an evulsion injury, an inverted U- or V-shaped flap of skin that remains attached at its upper margin.

Fractures

The fourth major variant of blunt injury is bone fracture. Bone may fracture in different ways according to the amount of force and the fashion in which it is applied. The classical transverse or V-like fracture of the lower leg as a result of being hit by a car bumper is likely to be different from the spiral twisting of the fracture sustained by a falling skier. Most of the time it is not easy to tell what happened because most of the bones are covered by tissue and the fracture sites may have been dressed to prevent infection. An observant, well-trained orthopedic surgeon, nurse, or paramedic may see features at the time of treatment that can help solve the classic “hit from the front, back, or side” question. It may be easier at autopsy because tissue can be removed and there is less blood to impede the examination, but even then detection may not be possible.

Summary

The four major varieties of blunt injuries have been reviewed. The principal points to note are the following:

• Abrasions, although not life threatening, can be of great assistance in working out what happened.

• Assessing the age or duration of bruises is difficult and unreliable.

• Laceration is a term that is widely misunderstood and misused. Lacerations result from blunt injuries and may be contaminated with foreign material or contain trace evidence. Lacerations of soft tissue, brought about by contact with angular objects in areas that overlie bone, may be mistaken for cuts.

• Directional characteristics are frequently present in abrasions and lacerations, and occasionally in fractures, although broken ends of bone are seldom examined with direction of force in mind (with the exception of bullet wounds).

Sharp Force Injuries

There are two main subdivisions of sharp injuries: cuts (which include slashes and slices) and stab wounds.

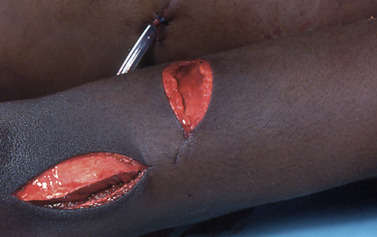

Cuts

In cuts, a sharp object comes against the skin with sufficient pressure to divide it. The force is usually directed mainly along the surface while some inward pressure is applied. Thus, such wounds are, by definition, longer than they are deep. Cuts may tail off at one end and be more superficial at one end than the other. The characteristics of the cutting instrument are usually not well reflected by a cut. After all, did a cut result from the last inch of a long blade or most of a short one? If only one edge did any cutting, how can one possibly tell anything about the edge that never made contact? It is also difficult to assess the amount of force required because this largely depends on the sharpness and configuration of the instrument and the resistance offered by clothing, if any (Fig. 25-6).

|

| Fig. 25-6 |

Two similar terms that refer to sharp injury are slash and slice. Slash means cutting or wounding with strokes or in a sweeping fashion with a sharp instrument or weapon: to gash, to strike violently or at random, to move rapidly or violently, to cut slits in, or to deliver cutting blows.

A slice is a relatively thin, flat, broad piece cut from the primary object, or it means a sharp cut or to cut cleanly.

Thus, these terms are commonly used in two circumstances:

1. When describing cuts on the wrists, neck, and other body parts of a person attempting suicide and as a descriptive term (e.g., “she slashed her wrists”)

2. In reference to reckless savage cutting, with overtly malicious intent, often forcefully and in a sweeping manner without careful aim. Such injuries are associated with gang wars, vendettas, crimes of passion, sex murders, control of prostitutes, and retaliation against suspected informants.

A slash, or slice, is a special variant of cut. Keep the following factors in mind when evaluating cuts:

• Cuts result from sharp objects coming against the skin with pressure to cause an injury.

• Cuts are longer than they are deep (in contrast to stab wounds).

• Cuts have clean-cut edges, usually without abrasion or bruising.

• In cuts, there is no bridging, spanning, or selective sparing of tissues.

• Overlying hair, the hair roots, and other small structures within the skin will be cut if the object is sufficiently sharp.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access