Populations Affected by Mental Illness

Jane Mahoney and Nancy Diacon

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Explain the concept of mental health, and discuss the importance of mental health promotion.

2. Discuss the historical context for contemporary mental health care.

3. Describe biological, social, and political factors associated with mental illness.

4. Illustrate the impact of natural and man-made disasters on the mental health of communities.

5. Describe some of the most common types of mental illnesses encountered in community settings.

6. Discuss the problem of suicide and recognize suicide warning signs.

8. Describe the role of mental health nurses in the community.

Key terms

agoraphobia

anorexia nervosa

anxiety disorders

attention deficit disorder

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

bipolar disorder

bulimia nervosa

Community Mental Health Centers Act

deinstitutionalization

depression

generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

major depression

mental health

mental illness

obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

panic disorder

Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act

phobia

posttraumatic stress disorder

Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT)

psychotherapeutic medications

schizophrenia

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

Mental health refers to the absence of mental disorders and to the ability for social and occupational functioning. Mental health can be affected by numerous factors, such as biological and genetic vulnerabilities, acute or chronic physical dysfunction, environmental conditions, and stressors. Threats to mental health are numerous and pervasive. Indeed, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) (2007) reported that more than 25% of adults 18 years of age and older have at least one mental disorder, and approximately 5% have three or more. Additionally, visits for mental illness and substance abuse in community health centers tripled from 2004 to 2009.

Community mental health nurses face multiple challenges such as complex patient comorbidity, lack of resources, the need for a broad base of expertise, physical facility inadequacies, and the stigma of mental illness, which affects clients and clinic staff (Cristofalo, Boutain, Schraufnagel et al., 2009). The purpose of this chapter is to describe critical issues that affect the mental health of individuals, families, groups, and communities and to explore the potential influence that nurses have on these issues. It also provides basic information on mental illnesses encountered in community settings and explores the environmental, biological, social, and political factors that influence mental health. Finally, some of the most commonly encountered options for management of mental illness are discussed.

Overview and history of community mental health

The 1999, the Surgeon General’s Report on Mental Health defined mental health as a state of successful performance of mental function that results in productive activities, fulfilling relationships with others, and an ability to adapt to change and cope with adversity. Mental illness includes all diagnosable mental disorders (i.e., those health conditions characterized by alterations in thinking, mood, or behavior associated with distress and/or impaired functioning). The report emphasized the importance of the mind-body connection and the detrimental effects of the stigma of mental illness (USDHHS, 1999).

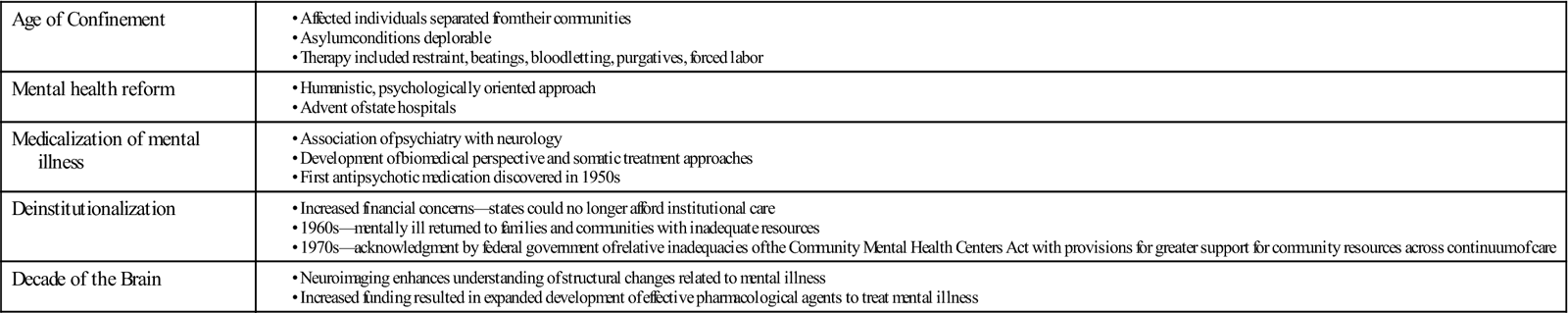

Since recorded history, communities have been caring for the mentally ill. The history of community mental health has included the Age of Confinement, mental health reform, medicalization of mental illness, deinstitutionalization, and Decade of the Brain. Historically, mental illness has been associated with behavior different from the social norm. Table 24-1 provides a snapshot of the evolutionary phases of community mental health.

TABLE 24-1

Evolutionary Phases of Community Mental Health

| Age of Confinement | |

| Mental health reform | |

| Medicalization of mental illness | |

| Deinstitutionalization | |

| Decade of the Brain |

Age of Confinement

The “Age of Confinement” refers to the early years of establishment of the colonies. Individuals whose behavior was inconsistent with social norms were labeled “mad,” separated from their communities, and placed in the custodial care of the state. Poverty, alcoholism, seizure disorders, and mental illness created rationale for asylum placement. Conditions in the asylums were deplorable. Individuals were often restrained, whipped, ill-fed, unwashed, and treated with bloodletting, purgatives, and other “curative” therapies. Madness was attributed to idleness; therefore, treatment included forced labor (Foucault, 1965; Hunter, 1963).

Mental Health Reform

By the end of the eighteenth century, inhumane conditions in houses of confinement gained the attention of philanthropists and humanists. A belief was established that humane treatment could abate mental illness. Humanistic person-centered principles replaced indentured servitude and confinement (Grob, 1991).

In the mid-nineteenth century, Dorothea Dix took up the cause of reform in the United States. Aided by changed attitudes toward suffering and social welfare, she helped effect reform in American hospitals and prisons. She established Saint Elizabeth’s Hospital in 1885 in Washington, DC, and eventually thirty-two state mental hospitals (Grob, 1983).

Medicalization of Mental Illness

After treatment reform in the mid- to late eighteenth century, collaborations were developed between the fields of psychiatry and neurology. This association proved to be pivotal for the development of psychiatry and community mental health. Scientific and political respectability for psychiatry depended on a biomedical perspective (Grob, 1983).

Numerous somatic treatments for mental illness followed biomedical theories, including lobotomy, electroconvulsive therapy, insulin shock therapy, and hydrotherapy (Deutsch, 1949). It was not until the early 1950s that the antipsychotic medication Thorazine (chlorpromazine) was discovered; this medication alleviated, in a more humane fashion, some of the most troubling symptoms experienced by individuals with psychotic disorders (Deutsch, 1949; Grob, 1991).

Community Mental Health and Deinstitutionalization

Treatment reform was based largely on the premise that mentally ill people were sick and in need of treatment. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, most states could no longer afford the expense of institutional care for the mentally ill. Caregivers, families, and communities became viable alternatives to costly institutional care.

In 1946, the National Mental Health Act established the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). In 1955, the Mental Health Study Act called for “an objective, thorough, nationwide analysis and reevaluation of the human and economic problems of mental health.” These efforts pointed to the need for a national program to help meet the needs of the mentally ill.

The Community Mental Health Centers Act of 1964 provided federal support for mental health services. The Act supported measures to implement facilities to care for those who were mentally retarded and to construct community mental health centers. The Act also mandated deinstitutionalization, or a halt to the long-held policy of keeping the severely mentally ill hospitalized. The intention was to reduce long-term care of seriously mentally ill persons, by transferring treatment to the community (Sharfstein, Stoline, and Koran, 2002).

Individuals with serious mental illness were returned to families and communities who were ill-prepared to care for them, compounding problems. Funding did not follow the change in policy, and many individuals with mental illness found themselves homeless, in shelters, or in prisons or jails, as families and communities were ill-prepared to deal with the shift to community-based care. Shortly thereafter, the federal government recommended linking community mental health services with informal community support services to improve treatment options.

Decade of the Brain

Although legislation improved environmental conditions, treatment for mental illness remained relatively unchanged. The development of neuroimaging in the 1980s provided new data on the anatomical and neurochemical nature of the brain (Buchsbaum and Haier, 1982). These data rendered the foundation for developing new pharmacological agents to treat mental illness. In the late 1980s, Congress declared the 1990s the Decade of the Brain (USDHHS, 1999) resulting in an increase in funding for the NIMH. An increased understanding of the biomedical components of mental illnesses led to new effective psychotropic medications (Kandel, 1998).

Although great strides have been made in understanding and treating mental illness, challenges remain for those affected by mental illness and those who work with mental illness in community settings. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have released data suggesting an ongoing prevalence of untreated mental illness within communities with great variability across states. It is estimated that 53.4% of individuals experiencing serious psychological distress go untreated in the United States. The percent untreated ranges from 33.3% in Alaska to 67% in Hawaii (Strine, Dhingra, Okoro et al., 2009). Factors such as social stigma or lack of transportation to facilities impact utilization of available services (Roberts, Robinson, Topp et al., 2008). Symptoms associated with mental illness may limit an individual’s capacity to make use of available resources. This may contribute to a lack of treatment effectiveness when services provided do not include a residential component (Burns, Robins, Hodge et al., 2009).

Healthy people 2020 and mental health

Healthy People 2020 is a broad-based collaborative effort among federal, state, and territorial governments and private, public, and nonprofit organizations to set national disease prevention and health promotion objectives to be achieved between 2010 and 2020 (USDHHS, 2009). The Healthy People 2020 table lists several objectives from Healthy People 2020 that cover issues related to mental health.

Factors influencing mental health

Treatment of mental disorders has dramatically improved, yet the cause of most mental illnesses is not well understood. Research has identified a number of biological and sociological factors that contribute to mental health and mental illness. Natural and man-made disasters also influence the mental health of individuals, families, and communities, and social and political factors that may be associated with development of mental illness. Some of these factors will be presented in this section.

Biological Factors

For centuries, mental illnesses were viewed as bizarre conditions that needed to be contained in institutions. Neuroscience research has provided a better understanding of the biology of mental illnesses; however, many questions remain unanswered. Biological factors associated with mental illness include genetic factors, neurotransmission, and brain structural and functioning abnormalities.

Genetic Factors

There is little information linking a specific gene to a specific disorder. Rather, the major psychiatric disorders appear to be genetically complex (Smoller, Sheidley, and Tsuang, 2008). Genetic expressions, combined with neurochemical and metabolic changes and environmental insults, may result in the display of mental disorder characteristics. A new field known as genetic imaging offers promise for understanding the complexities associated with gene variation, brain structure, and the physiological response to information processing (de Geus, Goldberg, Boomsma et al., 2008).

Neurotransmitters

In recent years, dysregulation in one or more neurotransmitter systems has been described in mental illness. No single neurotransmitter is implicated in any mental illness. Rather, the regulation/dysregulation of neurotransmission is complex and involves multiple intertwined neurotransmitters. For example, serotonin, dopamine, gamma-aminobutyric acid, and norepinephrine are involved in neurotransmission dysregulation associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (Olszewski and Varrasse, 2005).

Brain Structural and Functioning Abnormalities

Evidence indicates that structural brain abnormalities can be related to some mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, depression, and Alzheimer’s disease. As the science of neuroimaging evolves, a more refined view of the role of brain structure and functioning is unfolding. For example, neuroimaging studies are beginning to explain the role of different central nervous system structures in regulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis that controls responses to stress (Pruessner, Dedovic, Pruessner et al., 2010). Scientists are also recognizing how other systems of the body can impact brain functioning. For example, in one study researchers found a greater than 60% activation of the amygdala in sleep-deprived subjects as compared with controls. This suggests that sleep plays an important role in regulation in the emotional center of the brain (Yoo, Gujar, Hu et al., 2007).

Although a number of theories of the etiology of mental disorders have been developed, information is insufficient to establish a definitive biological cause for mental illness. Scholars have concluded that mental disorders are multifactorial, complex phenomena. The important point for community health nurses to understand is that mental illnesses have a very strong biological basis, much like other chronic conditions such as diabetes or heart disease, but other factors are highly influential.

Social Factors

Social factors can contribute to the etiology of mental illness (Institute of Medicine, 2006a; 2006b). Stress associated with social phenomena such as bullying, social rejection, domestic violence, and unemployment, for example, has been identified as causing mental illness (USDHHS, 1999). Mental illness also results in social isolation, which may compound the problem. Throughout history, the symptoms of mental illness have been perceived as permanent, dangerous, frightening, and shameful. People with a diagnosis of mental illness have been described as lazy, idle, weak, immoral, irrational, and feigning illness. On the basis of these characterizations and assumptions, many people with a diagnosis of mental illness have experienced widespread social rejection (Sadler, 2009). One of the key social implications of mental illness is the impact on the job market and employment. Individuals who have serious and persistent mental illness rarely have the luxury of private medical insurance because of the difficulties they experience in maintaining employment. In one study for example, researchers found that anxiety and depression had a major impact on employment outcomes among women (Cowell, Luo, and Masuda, 2009).

Another social concern is the trend for communities to make use of prisons rather than psychiatric hospitals as a solution to the “mental health problem.” The number of persons with mental illness in prison has quadrupled in the last 10 years, and nearly 50% of all inmates report mental health concerns (Human Rights Watch, 2008).

Prisons are woefully unprepared to provide adequate care to the mentally ill. To help address this problem, in 2008, Senate Bill S.2304—Mentally Ill Offender Treatment and Crime Reduction Reauthorization and Improvement Act was signed into law. This bill provided grants aimed at improving mental health treatment provided to criminal offenders with a mental illness. Other related initiatives have focused on establishing mental health courts in communities as a cost-effective means to address the needs of the community and those who are charged with a criminal offense and also experience a mental illness (Ridgely, Engberg, Greenberg et al., 2007). Thus, some progress is being made to promote social justice for the mentally ill, but there is a need for a much more intensive effort at creating structures and processes that support the treatment needs of the mentally ill in communities.

Natural and Man-made Disasters and Mental Illness

Natural and man-made disasters such as hurricanes, floods, violence, terrorism, war, and the global economic crisis are profound stress-inducing events that can lead to mental illness. Researchers reported high levels of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among survivors of Hurricane Katrina, the natural disaster that devastated New Orleans in 2005. Of those studied, 41% stated that they thought they would die; 16% witnessed someone become injured or die; 17% observed violence; and 6% experienced violence directly (Coker, Hanks, Eggleston et al., 2006). Furthermore, the levels of hurricane-related mental illness remained high years after the event (Kessler, Galea, Gruber et al., 2008). Community mental health nurses must not only be prepared to respond to the mental health needs of a community during a disaster, but also maintain vigilance in caring for survivors many years thereafter.

PTSD is highly prevalent among combat veterans returning from war to their homes and communities. PTSD is associated with extreme anxiety that can result in suicide. Male veterans in communities are twice as likely to die by suicide as their civilian counterparts (NIMH, 2007). In a report based on compiled data from sixteen states, the CDC (2005) noted approximately 1800 suicides by former or current military personnel that took place in 2005. Of those, nearly 30% had told someone of their intention to die by suicide within enough time for someone to have intervened. The tragedy of suicide to the victims, as well as to the surviving family members, friends, and community, is devastating. Early intervention is key to prevention and treatment.

The global economic crisis that began in late 2008 has led to enormous mental health consequences. The sense of hopelessness and powerlessness that accompanied the financial losses associated with dwindling retirement accounts for some, and layoffs for others, has contributed to much emotional distress throughout the world. The World Health Organization (2009) warned that the economic crisis will have a detrimental effect on the mental health of citizens of all nations and called for enhanced monitoring for indications of mental health decline.

Political Factors

Political factors can dramatically influence how mental disorders are managed. One significant factor in the politics of mental illness is parity in health care coverage, that is, the equal access to health care for physical and mental illnesses. Historically, health insurance companies have provided less access to treatment for a mental disorder than for a physical disorder. In 2008, the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act was enacted. The law requires health insurance to cover treatment for mental illness on the same terms and conditions as physical illness (Open Congress, 2008). Although this legislation is a victory for mental health, more laws are needed to provide improved mental health services to those who do not have access to health insurance.

Health care disparities have become a key issue in public health policy discussions. Members of ethnic minority groups have less access to mental health services than do their white counterparts. Minorities are more likely to delay seeking mental health care and are more likely to receive poor care when they are treated (Miranda, McGuire, Williams et al., 2008; USDHHS, 1999). There is a critical need to address this gap in health care.

Mental disorders encountered in community settings

The influence of untreated mental illness on communities and their social structure has been vastly understated. The NIMH estimates that the prevalence of diagnosable mental disorders in the U.S. population is about 26.2% at any given time. Approximately 6% have serious mental illness (Kessler, Chiu, Demler et al., 2005). Mental illness accounts for more than 10% of the disease burden worldwide, ranking it second, following all forms of cardiac disease (USDHHS/Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2005). In the United States, the estimated cost of mental illness exceeds $100 billion for costs of diagnosing and treating mental disorders and $193 billion in lost productivity (NIMH, 2008).

Recognizing that most mental illnesses are identified and managed in noninstitutional settings, it is essential that community health nurses be familiar with the most commonly occurring mental disorders. There is a need for screening, referring, and follow-up for those with mental health problems in order to meet the mental health needs of the community (Unutzer et al., 2006).

Overview of Selected Mental Disorders

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (fourth edition, text revision) (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000), classifies mental illnesses and outlines diagnostic criteria for more than 300 disorders. This section provides a summary of some of these disorders. More detailed information about specific disorders can be found at www.psychiatryonline.com.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is the most serious and profound of all mental illnesses; globally, it affects about 1% of the population (NIMH, 2005). The effect of this condition on the community is enormous in terms of social and economic burden. To the individual and families affected by schizophrenia, the impact is incalculable. It presents with (1) positive symptoms including hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thinking and speech, and bizarre behavior and (2) negative symptoms such as flat affect, poor attention, lack of motivation, apathy, lack of pleasure, and lack of energy. Onset typically occurs during late adolescence and early adulthood in males and somewhat later in females. There is an increased risk for alcohol use, depression, suicide, and diabetes among persons with schizophrenia. These factors compound the problems associated with living with a psychotic disorder.

Treatment for schizophrenia must be intensive and generally involves hospitalization (initially), antipsychotic medications, and psychotherapy/counseling. Long-term follow-up by mental health professionals is necessary to monitor medication compliance and to watch for side effects and complications, which may be severe and life threatening, and to evaluate the patient’s ability to integrate into the community.

Depression

Depression is the most frequently diagnosed and one of the most disabling mental illnesses in the United States. In 2004, more than 17 million adults experienced at least one major depressive episode (USDHHS/SAMHSA, 2005). Depression often co-occurs with serious physical disorders such as heart attack, stroke, diabetes, and cancer. About 25% of women and 12% of men will have at least one episode of depression during their lifetime. Although effective treatments exist, most people (almost two thirds) with depressive illness do not seek help (NIMH, 2000). Having a family or personal history of depression, suicide attempt, or sexual abuse, or current substance abuse or chronic medical condition increases the risk for depression (APA, 2000). Health education should include risk factor identification, as well as when and how to obtain treatment. Symptoms of depression are included in Box 24-1.

Depression in children and adolescents

According to the National Mental Health Association (2006), between 2% and 4% of prepubertal children and as many as 12% of adolescents may have depression. A family history of depression is a major risk factor for childhood depression. Other associated factors that may increase the risk of depression in children and adolescents include a history of verbal, physical, or sexual abuse; frequent separation from, or loss of, a loved one; poverty; mental retardation; attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; hyperactivity; and chronic illness. Children may refuse to go to school or pretend to be ill, and adolescents may appear sulky or irritable, common behaviors in this age group making identification of depression a challenge (NIMH, 2009). It should be noted that suicide is the third leading cause of death among persons 15 to 25 years and that the rate of suicide among young males is five times that among young females. Health care providers should recognize the symptoms of depression and refer for treatment as appropriate.

Treatment

Treatment for depression includes pharmacological therapy, psychotherapy, behavior therapy, electroconvulsive therapy, or a combination of these (APA, 2005; NIMH, 2009). In general, the most effective, first-line treatment is a combination of antidepressant medication and psychotherapy.

Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder refers to a group of mood disorders that present with changes in mood from depression to mania. The depressed phase is manifested by symptoms seen in major depressive disorder. The manic phase is characterized by a persistent abnormally elevated or irritable mood, impaired judgment, flight of ideas, pressured speech, grandiosity, distractibility, excessive involvement in goal-directed activities, few hours sleeping, and impulsivity. These symptoms may co-occur with psychotic features such as hallucinations and delusions. Persons with bipolar disorder are at increased risk for alcohol and substance abuse, as well as increased risk for suicide. The presence of bipolar disorder results in poor occupational and social functioning.

Management of bipolar disorder must be ongoing and involve close monitoring. Treatment generally involves use of mood-stabilizing medication, often in combination with antipsychotic and antidepressant therapy (APA, 2005). When working with persons with bipolar disorder, nurses need to monitor symptoms and response to psychopharmacological treatment.

Anxiety Disorder

Anxiety disorders are a group of conditions characterized by feelings of anxiety. Anxiety disorders affect up to 16% of the general population at any time. Anxiety disorders may be attributed to genetic makeup and life experiences of the individual. Some of the more commonly encountered anxiety disorders are generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder (sometimes accompanied by agoraphobia), phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and PTSD (APA, 2000). These are discussed briefly here.

Generalized anxiety disorder

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is characterized by chronic, unrealistic, and exaggerated worry and tension about one or more life circumstances lasting 6 months or longer (APA, 2000). Approximately half of cases of GAD begin in childhood or adolescence, and it is more common in women than in men. Symptoms of GAD include trembling, twitching, muscle tension, headaches, irritability, sweating or hot flashes, dyspnea, and nausea. Periods of increasing symptoms are usually associated with life stressors or impending difficulties.

Panic disorder

Approximately 6 million American adults have panic disorder (Kessler et al., 2005). Panic disorder can occur at any age, but it most often begins in young adulthood (average age, 17–30 years). Panic attacks consist of a period of intense fear that develops abruptly and unexpectedly. The initial attack may occur suddenly and unexpectedly while the client is performing everyday tasks. Typically, he or she experiences tachycardia; dyspnea; dizziness; chest pain; nausea; numbness or tingling of the hands and feet; trembling or shaking; sweating; choking; or a feeling that he or she is going to die, go crazy, or do something uncontrolled. This can be extremely frightening. A diagnosis of panic disorder is made when attacks occur with some degree of frequency or regularity.

As the disorder evolves, the anxiety attacks become increasingly frequent and severe, and the individual develops anticipatory anxiety (fear of having a panic attack). During this phase, events and circumstances associated with the attack may be selectively avoided, leading to phobic behaviors (e.g., if a woman has an attack while driving, she may become anxious the next time she needs to drive, and she may begin to avoid driving and then refuse to drive altogether). In this phase, the client’s life may become progressively constricted.

As the avoidance behavior intensifies, the client begins to withdraw further to avoid being in places or situations from which escape may be difficult or embarrassing or help may be unavailable in the event of a panic attack (e.g., church, elevators, movie theaters). The fear of being in these situations or places can lead to agoraphobia (literally, fear of the marketplace or open places). Individuals with agoraphobia frequently progress to the point where they cannot leave their homes without experiencing anxiety. Agoraphobia is the most common phobia leading to the use of health services, particularly when accompanied by panic attacks. Rates for co-occurring major depression range from 10% to 65% in persons with panic disorder (APA, 2000). Alcoholism is also common among individuals with panic disorders. Cognitive behavioral treatment and short-course benzodiazepines therapy are used to treat panic disorder.

Phobias

A phobia is an irrational fear of something (an object or situation), and as many as 8% of Americans are affected by phobias at any given time. Adults with phobias realize their fears are irrational, but facing the feared object or situation might bring on severe anxiety or a panic attack. Phobias may begin in childhood, but they usually first appear in adolescence or adulthood.

Social phobia, or social anxiety disorder, is a persistent and intense fear of, and compelling desire to avoid, something that would expose the individual to a situation that might be humiliating and embarrassing (APA, 2000). Its tendency is familial and may be accompanied by depression or alcoholism. The most common social phobia is a fear of public speaking. Other examples include being unable to urinate in a public bathroom and not being able to answer questions in social situations. Most people with social phobias can be treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication.

Simple phobias involve a persistent fear of, and compelling desire to avoid, certain objects or situations. Common objects of phobias are spiders, snakes, dogs, cats, and situations such as flying, heights, and closed-in spaces. The person often recognizes that the fear is unreasonable but avoids the situation or endures it with intense anxiety. Systematic desensitization and normal exposure are the most effective treatments for simple phobias.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by anxious thoughts and rituals that the individual has difficulty controlling. The person with OCD feels compelled to engage in some ritual to avoid a persistent frightening thought, idea, image, or event. Obsessions are recurrent thoughts, emotions, or impulses that cannot be dismissed. Compulsions are the rituals or behaviors that are repeatedly performed to prevent, neutralize, or dispel the dreaded obsession. When the individual tries to resist the compulsion, anxiety increases. Common compulsions include hand washing, counting, checking, or touching (APA, 2000). Most individuals recognize that what they are doing is senseless but are unable to control the compulsion. About 2% of Americans are afflicted with OCD, which often appears in the teenage years or early adulthood. Depression or other anxiety disorders often accompany OCD. Behavioral therapy and medication aimed at reducing accompanying symptoms have been found to be helpful.

Posttraumatic stress disorder

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a debilitating condition that follows a terrifying event. It affects about 3.5% of U.S. adults (Kessler et al., 2005). Individuals with PTSD have recurring, persistent, frightening thoughts and memories of their ordeal. Incidents may include “shell shock” or “battle fatigue” common to war veterans, violent attack, serious accidents, natural disasters, or witnessing mass destruction or injury, such as an airplane crash. Sometimes the individual is unable to recall an important aspect of the traumatic event. Highest incidence of PTSD occurs among combat-experienced military personnel (Smith, Ryan, Wingard et al., 2008). About 19% of Vietnam veterans, for example, have experienced PTSD (Dohrenwend, Turner, Turse et al., 2006).

People with PTSD repeatedly relive the trauma in the form of nightmares or disturbing recollections or flashbacks during the day, resulting in sleep disturbances, depression, and feelings of detachment or emotional numbness, or being easily startled. They may avoid places or situations that bring back memories (e.g., a woman raped in an elevator may refuse to ride in elevators), and anniversaries of the event are often very difficult. PTSD occurs at all ages and may be accompanied by depression, substance abuse, and/or anxiety. It usually begins within 3 months of the trauma, and the course of the disorder varies. Some individuals recover within 6 months; the condition becomes chronic in others. Infrequently, the illness does not manifest until years after the traumatic event. Treatment includes antidepressants and antianxiety medications and psychotherapy. Support from family and friends can be very beneficial.

Eating Disorders

Eating disorders, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, are increasingly prevalent in the United States, affecting about 3 million U.S. residents. Anorexia affects about 0.5% to 3.7% of females in their lifetime (NIMH, 2009), and as many as 4% to 15% of female high school and college women have some symptoms of bulimia (Cochrane, 2005).

Eating disorders primarily affect females; males account for 5% to 10% of cases, although this may be underreported. Most clients with a diagnosis of eating disorders are white; however, this may be because of socioeconomic factors rather than race. Anorexia and bulimia are often triggered by developmental milestones (e.g., puberty, first sexual contact) or another crisis (e.g., death of a loved one, ridicule over weight, starting college).

Bulimia nervosa

Bulimia nervosa refers to binge eating, discreetly consuming an abnormally large amount of food, accompanied by maladaptive compensatory methods to prevent weight gain (APA, 2000). For example, a person with bulimia might eat an entire pie, half a cake, or a half gallon of ice cream at one sitting. Snacking throughout the day is not considered bingeing. To lose or maintain weight, the person with bulimia practices purging, which usually involves self-induced vomiting, caused by gagging, using an emetic, or simply mentally willing the action. Laxatives, diuretics, fasting, and excessive exercise may also be employed to control weight.

Bulimia nervosa typically begins in adolescence or during the early 20s, usually in conjunction with a diet. High school and college students, as well as members of certain professions that emphasize weight and/or appearance (e.g., dancers, flight attendants, cheerleaders, athletes, actors, models), are at high risk. The condition may lead to electrolyte imbalance resulting in fatigue, seizures, muscle cramps, arrhythmias, and decreased bone density. Vomiting can damage the esophagus, stomach, teeth, and gums.

Anorexia nervosa

The person with anorexia nervosa becomes obsessed with a fear of fat and with losing weight. Anorexia nervosa often develops with a fairly gradual decrease in caloric intake. However, the decrease in caloric intake continues until the person is consuming almost nothing. Anorexia usually begins in early adolescence (12 to 14 years is the most common age-group) and may be limited to a single episode of dramatic weight loss within a few months, followed by recovery, or the illness may last for many years.

Risk factors for eating disorders are perfectionism, low self-esteem, stress, poor coping skills, sexual/physical abuse, poor self-image, dependency on others’ opinions and deference to others’ wishes, and being emotionally reserved (Cochrane, 2005). In response to the severely decreased caloric intake, the body tries to compensate by slowing down body processes. Menstruation ceases; blood pressure, pulse, and respiration rates slow; and thyroid activity diminishes. Electrolyte imbalance can become very severe. Other symptoms include mild anemia, joint swelling, and reduced muscle mass. Anorexia nervosa can be life threatening and has a mortality rate of 5% to 21%.

Treatment for eating disorders includes long-term nutrition counseling, psychotherapy, and behavior modification. Hospitalization may be required for clients with serious complications. Self-help groups and support groups can be very beneficial for both the client and the family.

Nurses need to be aware of the “ProAna” websites, which promote the lifestyle associated with eating disorders. Such knowledge is important, as community health nurses assess the social influences that contribute to the condition. Also, nurses who frequently work with adolescent girls and young women in community settings such as schools and clinics should be aware of the risk factors, signs, and symptoms of anorexia and bulimia and be prepared to intervene.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Two of the most common conditions encountered by nurses who work with children in community settings are attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and attention deficit disorder (ADD). ADHD/ADD affects 4.5 million children in the United States (CDC, 2009). Behaviors that might indicate ADHD/ADD usually appear before age 7 years and are often accompanied by related problems, such as learning disability, anxiety, and depression. The three major characteristics of ADHD/ADD are inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity.

The cause of ADHD/ADD is not known, but it is important to note that it is not caused by minor head injuries, birth complications, food allergies, too much sugar, poor home life, poor schools, or too much television. Maternal substance use and abuse (e.g., alcohol, cigarettes, cocaine) may affect the brain of the developing baby and produce symptoms of ADHD/ADD later in life. This, however, accounts for only a small percentage of those affected. Attention disorders run in families.

Although parents may notice symptoms and signs, it is often teachers who recognize the behaviors consistent with attention deficit disorders and suggest referral for assessment and treatment (NIMH, 2009). Experts caution that diagnosis of attention disorders should be made following a comprehensive physical, psychological, social, and behavioral evaluation and not based solely on anecdotal reports from parents or teachers. The evaluation should rule out other possible reasons for the behavior (e.g., emotional problems, poor vision or hearing, physical problems) and should include input from teachers, parents, and others who know the child well. Intelligence and achievement testing may also be performed to rule out or identify a learning disability.

Symptoms of ADHD/ADD are typically managed through a combination of behavior therapy, emotional counseling, and practical support. Use of medication is becoming increasingly commonplace in the management of ADHD/ADD. It is very important, however, that children with attention disorders and their families understand that medication does not cure the disorder; it just temporarily controls symptoms.

Stimulants have been shown to be successful in treating attention disorders. The most commonly used medications are methylphenidate (Ritalin) and amphetamines (Dexedrine, Dextrostat, or Adderall). Appetite suppression and poor sleep are common side effects. Body mass index monitoring and sleep promotion strategies are important (NIMH, 2009).

Suicide

There are approximately 1 million deaths by suicide per year throughout the world, and that number is projected to remain about the same through 2015 (Mathers and Loncar, 2005). The National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2009) reported there were more than 30,000 deaths by suicide in the United States in 2006. Suicide is the third leading cause of death among those aged 15 to 24 years. The highest rate of suicide occurs in males over 65 years of age; white males over the age of 85 years are particularly vulnerable.

In 1999, the USDHHS and the Office of the Surgeon General identified suicide as a primary public health problem of the new millennium. Consistent with the select aims of Healthy People 2020, the Surgeon General’s Call to Action attempts to “put into place national strategies to prevent the loss of life and the suffering suicide causes” (USDHHS, 1999, p. 7) through increased public awareness, expansion of mental health services, and continuation of support of research aimed at understanding and preventing suicide in the United States.

Historically, risk and protective factors have been used to identify those at highest risk for suicide. Recently, the American Association of Suicidology (AAS) (2008) has recommended recognition of warning signs as more relevant than risk and protective factors in preventing death by suicide. The AAS has organized the warning signs according to the easily remembered mnemonic, IS PATH WARM (Table 24-2). Recognizing the suicide-related behaviors that are occurring in the moment is more useful to health care providers than understanding risk factors that may have no bearing on the current situation and may not be modifiable. For example, if a person has a history of a previous suicide attempt, that does not mean that person is at risk of attempting suicide at any given moment. However, if a person is talking about suicide and describing feeling very anxious and trapped, the indications are much stronger that there is an imminent threat. Warning signs that indicate acute risk for suicidality may be observed in individuals who are threatening to hurt or kill themselves, attempting to identify access to lethal weapons or other means that could result in death, or communicating about dying when these thoughts or actions are out of the ordinary for them.

TABLE 24-2

Suicide Warning Signs: Is Path Warm

| Ideation | Does the person state that he or she is having thoughts of suicide? |

| Substance abuse | Is the person demonstrating increased use of alcohol or drugs? |

| Purposelessness | Does the person state that he or she feels as if there is no purpose in his or her life? |

| Anxiety | Is the person demonstrating anxiety-related behaviors such as: talking about being overly worried about things, ruminating, difficulty concentrating, or exhibiting increased psychomotor agitation? |

| Trapped | Does the person state that he or she feels trapped, that there is no way out of the current situation except to die? |

| Hopelessness | Does the person state that he or she feels hopeless? Is the person able to describe something to look forward to? |

| Withdrawal | Is the person withdrawing from others such as family and friends? Is the person isolating? |

| Anger | Is the person demonstrating uncontrolled anger? Is the person acting with rage or seeking revenge? |

| Recklessness | Is the person engaged in risk-taking behaviors? Is the person acting as if he or she “doesn’t care” or isn’t thinking about the consequences of the risk-taking behavior? |

| Mood changes | Is the person experiencing dramatic mood changes? |

From American Association of Suicidology: Know the warning signs, 2009: www.suicidology.org.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Healthy People 2020

Healthy People 2020