CHAPTER 24. Abdominal and Genitourinary Trauma

Vicki Bacidore

Abdominal injuries are a significant source of morbidity and mortality, ranking third as a cause oftraumatic death, preceded only by injuries to the head and chest. Although both penetrating and blunt injuries are common, blunt abdominal trauma is the leading cause of death and disability across all age-groups. One of the most frequent causes of preventable death is an abdominal injury that is unrecognized or missed by the emergency care provider. 13 The emergency nurse should initially manage patients with abdominal trauma in the same manner as all other trauma patients. Evaluation should begin with a rapid assessment and concurrent emergency management of any airway, breathing, circulation, and disability issues.

An understanding of the mechanism of injury and the forces involved in the wounding event allows the team to focus its assessment and raises the suspicion of specific organ involvement. Blunt injury occurs most often from motor vehicle crashes (MVCs). These injuries are often related to mechanisms of shearing, tearing, or direct-impact forces. Blunt abdominal trauma has a higher mortality rate than penetrating injuries because blunt injuries are more difficult to detect and are often associated with other concomitant injuries to the head, chest, and extremities. Multiple abdominal organ injuries are associated with higher mortality. Penetrating injuries are often caused by gunshots or stabbings but can be due to any sharp object. Stab injuries occur almost three times more often than gunshot injuries, are usually less destructive, and have a much lower mortality rate. 7 Penetrating trauma is more likely to involve vascular structures. Gunshot wounds can be deceiving because there is almost always some blast effect, and the dissipation of kinetic energy can damage structures that were not in direct contact with the bullet. Also, because of the force involved, the wound tract can close in on itself, making an accurate estimate of tissue damage difficult. See Chapter 20 for further discussion on blunt and penetrating trauma.

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

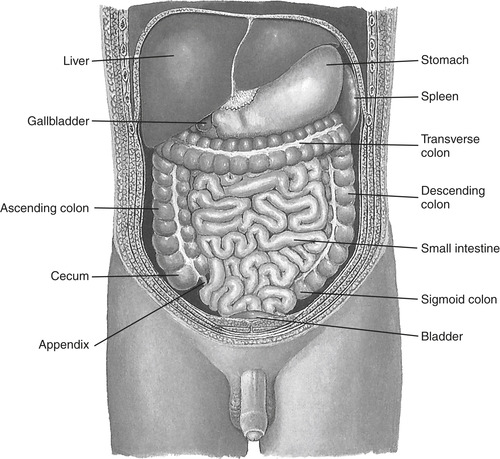

Knowledge of the anatomic boundaries of the abdomen is important as one considers injury patterns, such as hollow-organ injury, vascular injury, solid organ injury, or injuries to the retroperitoneal area (Figure 24-1). The oval-shaped abdominal cavity extends from the dome-shaped diaphragm, a large muscle separating the thoracic cavity from the abdomen, to the pelvic brim. The pelvic brim stretches at an angle from the intervertebral disk between L5 and S1 to the pubic symphysis.

|

| FIGURE 24-1 Abdominal viscera. (From Seidel HM et al: Mosby’s guide to physical examination, ed 6, St. Louis, 2006, Mosby.) |

The abdomen is divided into three sections: the anterior abdomen, the flanks, and the posterior abdomen or back. The outer boundary of the abdominal cavity is the abdominal wall on the front of the body and the peritoneal surface on the back of the body. The abdomen extends upward into the lower thorax at about the level of the nipples or the fourth intercostal space. The anterior part of the abdomen extends inferiorly to the inguinal ligaments and symphysis pubis, and laterally to the front of the axillary line. The flanks include the regions between the anterior and posterior axillary lines from the sixth intercostal space to the iliac crest. The back extends posteriorly between the posterior axillary lines, from the scapula to the iliac crests. The flanks and the back are protected by thick abdominal wall muscles that protect the region from low-velocity penetrating trauma.

Peritoneum

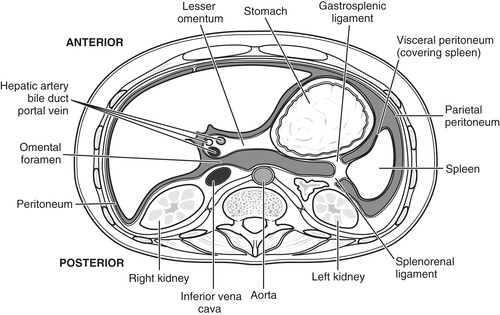

The peritoneum is a smooth, serous membrane that provides cover to the abdominal structures and allows the viscera to move within the abdomen without friction. The parietal peritoneum lines the abdominal wall, and the visceral peritoneum surrounds the organs of the abdomen. The mesenteries are double layers of the peritoneum; they surround, supply blood, and attach organs like the large and small bowel to the abdominal wall. Organs in the retroperitoneal space (e.g., kidneys, parts of the colon, duodenum, pancreas, aorta, and inferior vena cava) (Figure 24-2) are only partially covered by the peritoneum. In men the peritoneum is closed, but in women it is open where the ends of the fallopian tubes communicate with the peritoneum.

|

| FIGURE 24-2 Retroperitoneal structures. |

Solid Organs

The liver is a solid organ and is the largest organ in the abdomen. It is located in the right upper quadrant (RUQ) with extension into the midline and is extremely vascular. Circulation is through the hepatic artery and portal vein and represents about 30% of the total cardiac output. Aside from its metabolic functions, the liver releases bile to aid in fat emulsification and the absorption of fatty acids. It also filters and stores up to 500 mL of blood at any given time.

The spleen is also a large vascular organ located in the left upper quadrant (LUQ), beneath the diaphragm at the level of the ninth through eleventh ribs. The spleen is important in the body’s immune function for its clearance of bacteria. It also filters and stores up to 200 mL of blood.

The gallbladder is a saclike organ located on the lower surface of the liver that acts as a reservoir for bile, one of the digestive enzymes produced by the liver. The liver continually secretes bile, and the gallbladder stores it until it is released through the cystic duct during the digestive process.

The kidneys are retroperitoneal organs that lie at the level of the twelfth thoracic vertebra to the third lumbar vertebra. The kidneys lie posterior to the stomach, spleen, colonic flexure, and small bowel. They are enclosed in a capsule of fatty tissue and a layer of renal fascia, which maintains their position. They are well protected by the vertebral bodies and the back muscles, as well as the abdominal viscera. They are protected because of their deep location in the retroperitoneal space and by abdominal contents, muscles, and the vertebral spine. They filter blood and excrete body wastes in the form of urine.

The pancreas is located behind the stomach along the abdomen’s posterior wall in the retroperitoneum. Its exocrine cells produce enzymes, electrolytes, and bicarbonate to assist in the digestion and absorption of nutrients. Its endocrine cells produce insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin, which are involved in carbohydrate metabolism.

Hollow Organs

The stomach is located in the LUQ between the liver and spleen at the level of the seventh and ninth ribs. Entry to the stomach is controlled by the lower esophageal sphincter (sometimes referred to as the cardiac sphincter), and exit is controlled by the pyloric sphincter. The stomach stores food, secretes acidic gastric secretions, mixes food with the secretions, and then propels the mixture into the duodenum.

The small bowel connects to the pyloric sphincter and fills most of the abdominal cavity because it is approximately 7 m long. It is composed of three sections: duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, and it is held in position by the adjacent viscera, the peritoneal membrane attachments to the posterior abdominal wall, and ligaments. It functions by releasing enzymes that aid in digestion and absorption.

The large bowel is about 1.5 m long; it connects with the ileum proximally and ends distally at the rectum. Its divisions consist of the ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and the sigmoid colon. The primary functions of the large bowel are to absorb water and nutrients and store fecal matter until it can be eliminated.

The urinary bladder is an extraperitoneal organ that stores urine. When empty, it lies in the pelvic cavity, and when full, it can expand into the abdomen. Its blood supply is large and derived from branches of the iliac artery. The ureters are a pair of thick-walled, hollow tubes that carry urine from the kidneys to the urinary bladder. The female urethra is short and well protected by the symphysis pubis, whereas the male urethra is about 20 cm long and lies mostly outside of the body.

Reproductive Organs

The abdomen also contains organs of the reproductive system. The female reproductive system contains the uterus, a pear-shaped organ that allows implantation, growth, and nourishment of a fetus during pregnancy. The nongravid uterus is in the pelvis, and the gravid uterus is in the midline of the lower abdomen. The female ovaries, located in the pelvis, one on each side of the uterus, produce the precursors to mature eggs and produce hormones that regulate female reproductive function.

The male reproductive system contains the penis, the male external reproductive organ, as well as the testes. The penis has three vascular bodies (erectile tissue): the paired corpora cavernosa and the corpus spongiosum. A testis and epididymis lie in each scrotal compartment. Testicular blood supply is obtained via the spermatic cord and the testicular artery, the artery to the vas deferens, and the cremasteric artery. The scrotum is covered by a thin layer of skin and obtains its blood supply via the branches of the femoral and internal pudendal arteries.

Vascular Structures

The abdominal aorta lies left of the midline and bifurcates into the iliac arteries, which supply blood to the lower extremities. Three unpaired arteries originating from the abdominal aorta (the celiac trunk and the superior and inferior mesentery arteries) supply the abdominal organs. The celiac trunk branches into the hepatic, left gastric, and splenic arteries. The inferior vena cava is the major vein in the abdomen.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT

History

Because the patient with abdominal trauma may not exhibit any obvious injuries, it should be suspected based on the patient’s chief complaint and mechanism of injury. Abdominal trauma should also be considered in a patient with multisystem trauma or history of injury with unexplained hypotension or tachycardia. Complaints of pain, rigidity, guarding, or spasms in the abdominal musculature are classic signs of intraabdominal injury. Peritoneal membranes may be irritated due to free blood, air, or gastric or intestinal contents within the peritoneal cavity. Irritation of the inferior surface of the diaphragm and phrenic nerve can cause referred pain to the left shoulder This finding, known as Kehr’s sign, should alert the trauma nurse to a possible splenic injury. Patient history and assessment triggers that require further evaluation include the following12:

1. Presence of abdominal pain, tenderness, or distension

2. Mechanism of injury and prehospital details suggest potential for injury

3. Lower chest or pelvic injury

4. High-speed collisions or collisions in which there has been substantial deformity to the vehicle (particularly if the patient was unrestrained)

5. MVCs with fatalities or those in which there were others with substantial injuries

6. Unprotected injury (i.e., motorcycle crashes)

7. Inability to tolerate a delayed diagnosis (e.g., older adults, those with significant comorbid diseases)

8. Presence of distracting injuries (e.g., long-bone fractures)

9. Decreased level of consciousness/altered sensorium

10. Pain-masking drugs (e.g., ethanol, opiates)

Mechanisms of Injury

Understanding the mechanism of injury, the type of force applied, and the tissue density of the injured organ (solid, hollow) aids the trauma team by focusing the assessment and having a high index of suspicion regarding specific organ involvement. Blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma can cause extensive injury to the viscera, resulting in massive blood loss, spillage of intestinal contents into the peritoneal space, and peritonitis.

Blunt

Blunt trauma is the most common mechanism of injury seen in the United States; motor vehicle collisions are the leading mode of injury. This diffuse injury pattern puts all abdominal organs at risk for injury. The biomechanics of blunt injury involve a compression or crushing by direct energy transmission. If the compressive, shearing, or stretching forces exceed tissue tolerance limits, they are disrupted. This may result in injury to solid viscera (liver, spleen) or rupture of hollow viscera (gastrointestinal tract). Injury also can result from the movement of organs within the body. Some organs are rigidly fixed in place, whereas others are semifixed by ligaments, such as the mesenteric attachments of the intestines. During energy transfer, longitudinal shearing forces may cause rupture of these organs at their attachment points or where the blood vessels enter the organ. Examples of structures semifixed in place and therefore susceptible to injury include the mesentery and small bowel, particularly at the ligament of Treitz or at the junction of the distal small bowel and right colon. Falls from a height produce a unique pattern of injury. In this case, injury severity is a function of distance and the surface on which the victim lands. Intraabdominal injuries are uncommon from vertical falls; hollow visceral rupture is most frequent. Retroperitoneal injuries with significant blood loss, however, are common because force is transmitted up the axial skeleton.

Penetrating

Stab wounds directly injure tissue as the blade passes through the body. External examination of the wound may underestimate internal damage and cannot define the trajectory of the blade. Any stab wound in the lower chest, pelvis, flank, or back has caused abdominal injury until proven otherwise. Gunshot wounds injure in several ways. Bullets may injure organs directly, via secondary missiles such as bone or bullet fragments, or from energy transmitted from the bullet. Bullets designed to break apart once they enter a victim cause much more tissue destruction than a bullet that remains intact. Tissue disruptions presumed to be entrance and exit wounds can approximate the missile trajectory. Plain radiographs help to localize the foreign body, allowing prediction of organs at risk. Unfortunately, bullets may not travel in a straight line. Thus all structures in any proximity to the presumed trajectory must be considered injured. 12

Motor Vehicle Crashes

In MVCs there are five typical patterns of impact: frontal, lateral, rear, rotational, and rollover. Each of these different mechanisms, with the exception of rear impact, has the potential to cause significant injury to the abdominal organs. In a rear-impact collision, the patient is less likely to have an abdominal injury if proper vehicular restraints are used. However, if restraints are improperly worn or not used at all, the potential for injury is great. Rollover impacts present the greatest potential to inflict lethal injuries. Unrestrained occupants may change direction several times with an increased risk for ejection from the vehicle. The occupants involved in a rollover may collide with each other, as well as with the vehicle interior, producing a wide range of potential injuries.

Inspection

Observe the lower chest for asymmetric chest wall movement, which may indicate lower rib fractures and liver, spleen or diaphragmatic injury. Look at the contour of the abdomen: distension may be due to massive bleeding, pneumoperitoneum, gastric dilation, or ileus produced by peritoneal irritation; a flat or concave abdomen may be indicative of a ruptured diaphragm with herniation of abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity. Assess for bruising, abrasions, or lacerations. Ecchymosis in the LUQ may indicate soft tissue injury or a splenic injury. Bruising or patterning over where the seat belt would be located or steering wheel–shaped contusions suggest a significant mechanism of injury, and other intraabdominal injuries should be suspected. Cullen’s sign (i.e., periumbilical ecchymosis) may indicate intraperitoneal hemorrhage; however, this symptom usually takes several hours to develop. Flank bruising, Grey Turner’s sign, may raise suspicion for retroperitoneal injury and bleeding. Old surgical scars should be noted because this may help narrow the search for organs that may be injured. Inspect for gunshot or stab wounds, and inspect the pelvic area for soft tissue bruising.

Percussion and Auscultation

Percussion has been used to detect the presence of free fluid in the abdomen. With the ready availability of more sensitive, noninvasive diagnostic techniques (e.g., ultrasonography and computed tomography [CT]), listening to percussion sounds to diagnose abdominal injury is outmoded.

All four quadrants of the abdomen should be auscultated for the presence and frequency of bowel sounds. The presence of bowel sounds is a reassuring indicator of peristalsis, but it is not reliable for ruling out visceral injuries. Up to 30% of patients have active bowel sounds in the presence of intraperitoneal bleeding or rupture of hollow viscera. Conversely, about 30% of patients who have absolutely no bowel sounds after careful listening for at least 5 minutes have no visceral damage. 15 An abdominal bruit may indicate underlying vascular disease or traumatic arteriovenous fistula. Auscultation of bowel sounds in the thoracic cavity, especially on the left side, may indicate the presence of a diaphragmatic injury.

Palpation

Beginning in an area where the patient has not complained of pain, palpate the abdomen for pain, rigidity, tenderness, and guarding in all four quadrants. To determine the presence of rebound tenderness, press on the abdomen and quickly release. Fullness and doughy consistency may indicate intraabdominal hemorrhage. Crepitus or instability of the lower thoracic cage indicates the potential for splenic or hepatic injuries associated with lower rib injuries. Pelvic instability indicates the potential for lower urinary tract injury, as well as pelvic and retroperitoneal hematoma.

Initial Stabilization

Initial stabilization of the patient with abdominal or genitourinary (GU) trauma follows the same sequence as for any patient with major trauma and begins by securing airway, breathing, and circulation. Two large-bore intravenous (IV) catheters should be secured for administration of crystalloids (e.g., lactated Ringer’s solution or normal saline), blood products, and medications. Baseline laboratory studies are obtained, as well as a pregnancy test for any woman of childbearing age. Efforts should be made to limit hypothermia, including use of warm blankets and prewarmed fluids.

Medications

Analgesia

Pain relief is appropriate for most injuries. Morphine sulfate 2 to 5 mg or 0.1 mg/kg IV is commonly used. Fentanyl 50 to 100 mcg IV is an alternative agent. It has less histamine release than morphine and thus causes less hypotension; its shorter duration of action may be advantageous in trauma situations in which serial examinations are required. Avoid medications with antiplatelet activity potential such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

Antibiotics

Anaerobes and coliforms are the predominant organisms found in cases of intestinal perforation, and antibiotics active against these organisms should be given to decrease the incidence of intraabdominal sepsis.

Emergency Department Interventions

Urinary Catheter

A urinary catheter should be inserted to monitor urine output in all patients with major trauma. Before inserting a urinary catheter in patients with severe blunt trauma, a rectal examination needs to be performed to check the position of the prostate, look for any rectal blood, and check sphincter tone. If there is any suspicion of damage to the urethra as evidenced by blood at the urethral meatus, penile or perineal hematomas, a displaced prostate, or a severe anterior pelvic fracture, a retrograde urethrogram should be performed before a urinary catheter is inserted. 15

Gastric Decompression

Early gastric decompression with a gastric tube is particularly important when there is a possibility of intraabdominal visceral damage or when the patient may have eaten or drunk recently. All trauma patients should be assumed to have full stomachs, even if they deny recent ingestion of food or liquids. The gastric tube may be a valuable diagnostic tool for revealing injury to the upper gastrointestinal tract; oral rather than nasal insertion of the tube is recommended in patients with concurrent head injury (i.e., basilar skull fracture) or midface injuries. Injured patients tend to swallow air, especially if they have any respiratory distress. Patients resuscitated with a bag-mask device can also have large amounts of air forced into their stomachs. The resulting distension of the stomach not only increases the chances of vomiting and aspirating, but also raises the diaphragm, increasing the resistance to ventilation.

Wound Care

Penetrating wounds should be covered with sterile dressings. In cases of traumatic eviscerations, the intraabdominal contents extrude through the abdominal wall and are exposed to the environment. To prevent further injury and to keep the exposed organs viable for surgical replacement, the extruded contents must be kept moist at all times with sterile saline–soaked dressings. 3 Eviscerated organs, especially the small bowel, should never be allowed to dry out. Never attempt to push the eviscerated contents back into the peritoneal cavity, which may further injure the tissue. 16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access