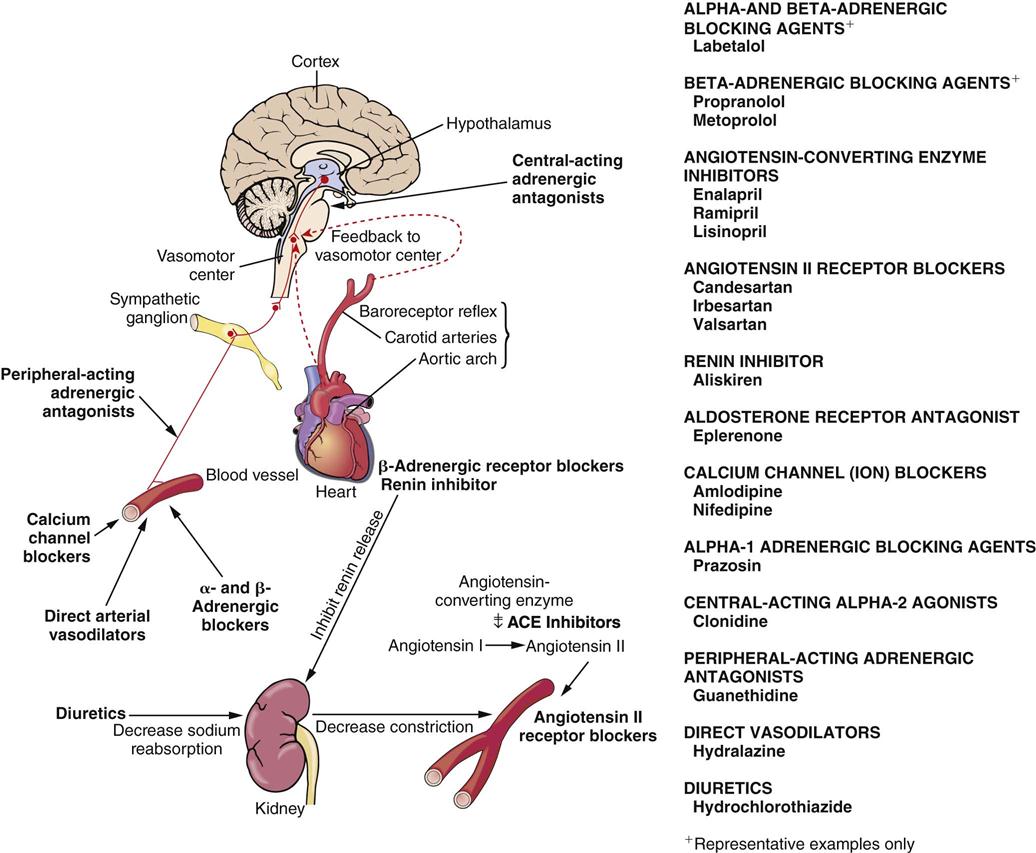

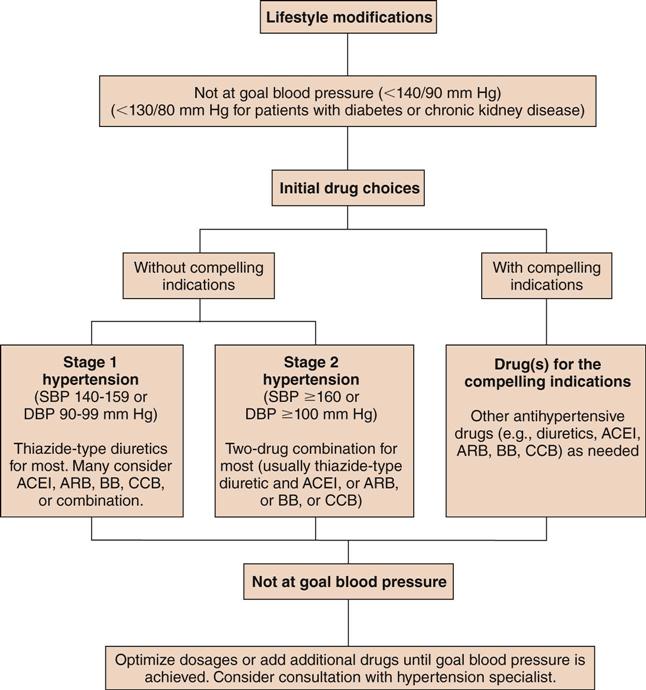

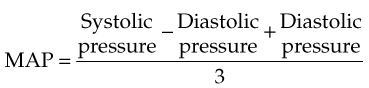

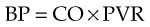

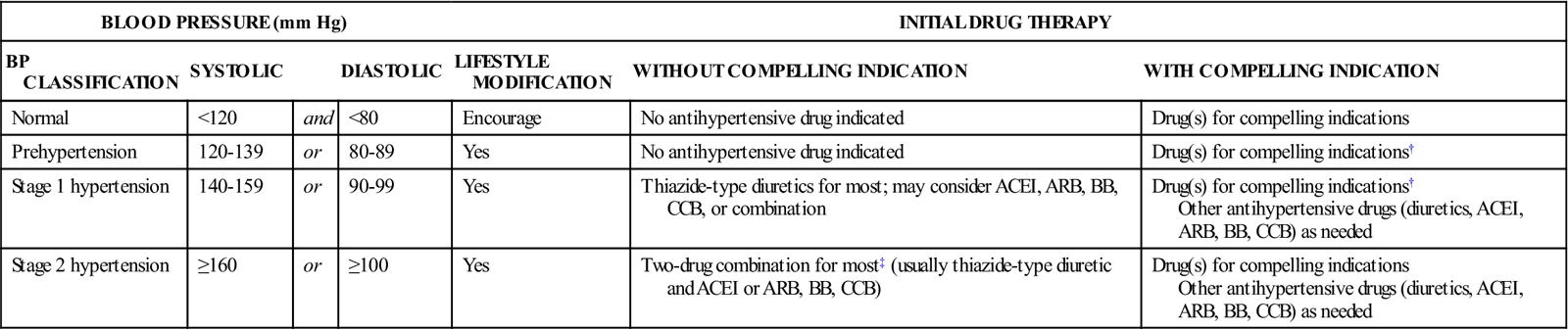

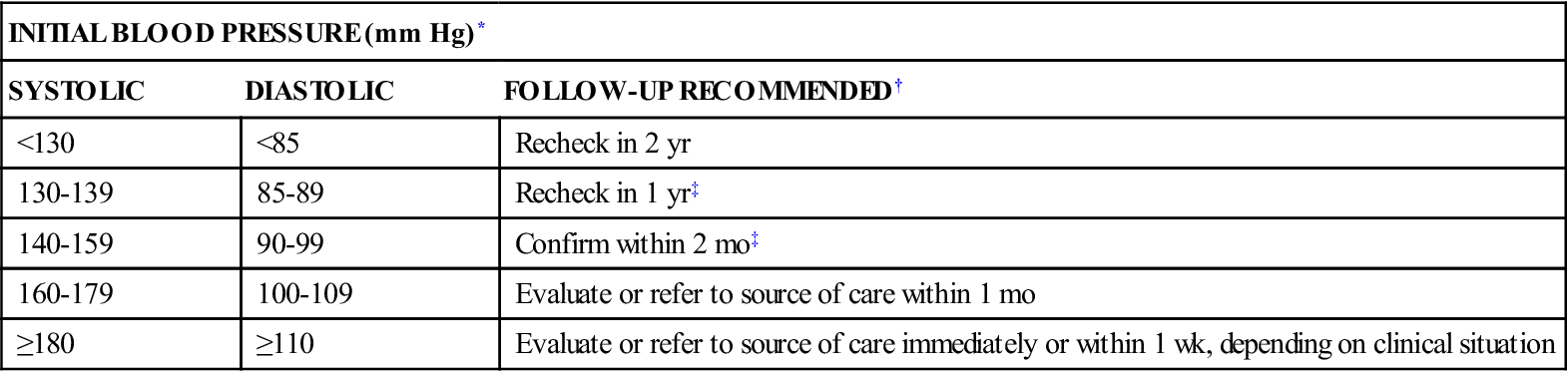

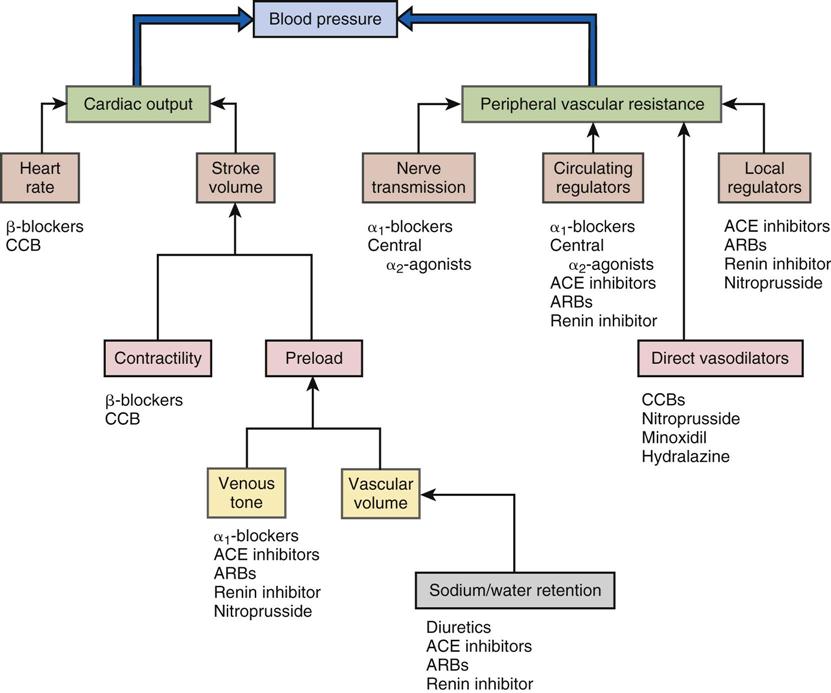

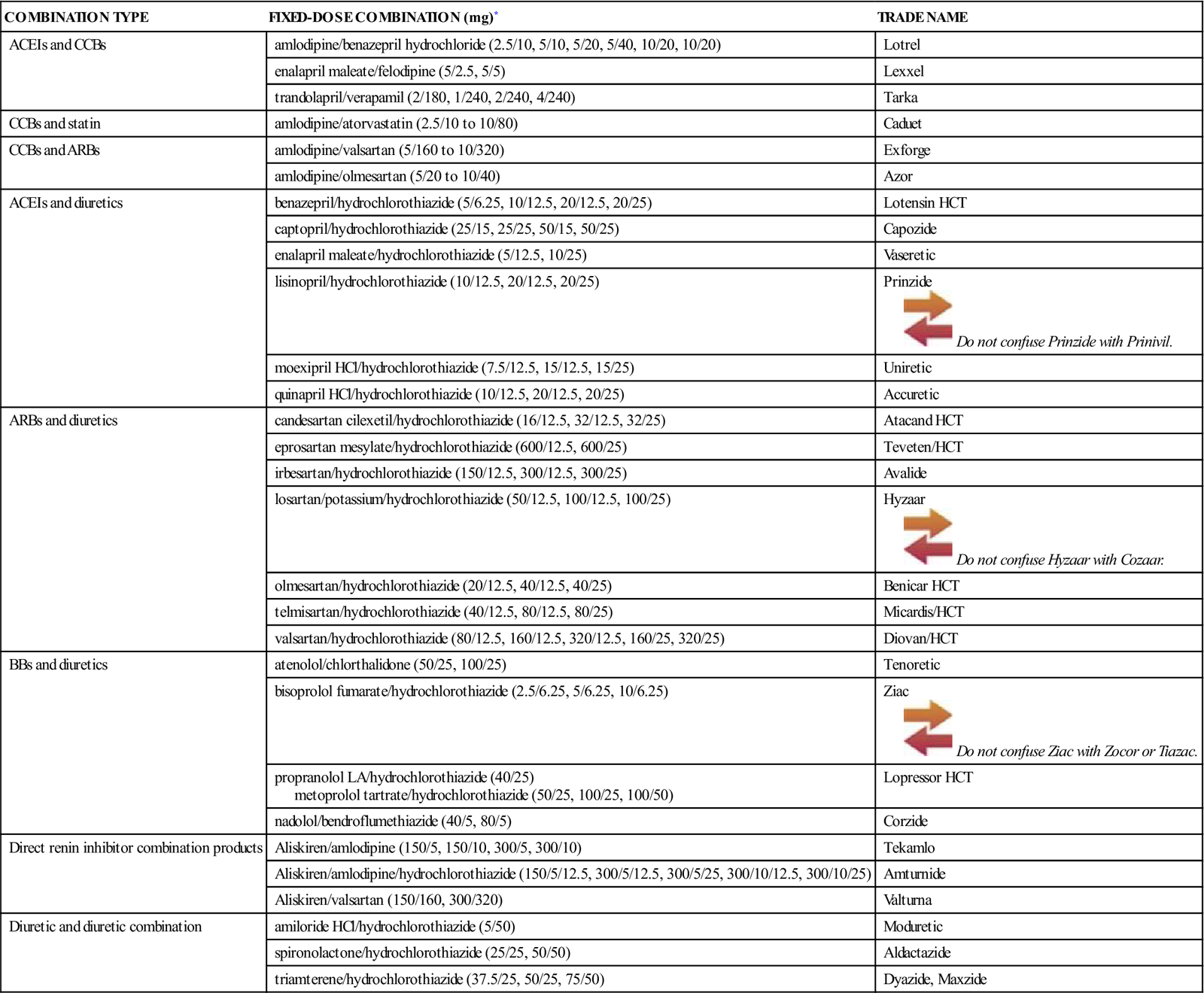

1 Discuss blood pressure and how to correctly measure blood pressure. 2 Define hypertension and differentiate between primary and secondary hypertension. 3 Summarize nursing assessments and interventions used for the treatment of hypertension. 4 Identify recommended lifestyle modifications for a diagnosis of hypertension. 5 Identify options and progression of treatment for hypertension (see Figure 23-2). 6 Discuss specific risk factors the hypertensive patient can manage. 7 Identify and summarize the action of several of the drug classes used to treat hypertension. arterial blood pressure ( systolic blood pressure ( diastolic blood pressure ( pulse pressure ( mean arterial pressure (MAP) ( cardiac output (CO) ( hypertension ( primary hypertension ( secondary hypertension ( systolic hypertension (p. 358) See Chapter 21 for an introduction to cardiovascular diseases. A primary function of the heart is to circulate blood to the organs and tissues of the body. When the heart contracts (systole), blood is pumped from the right ventricle out through the pulmonary artery to the lungs as well as from the left ventricle out through the aorta to the other organs and peripheral tissues. The pressure with which the blood is pumped from the heart is referred to as the arterial blood pressure or systolic blood pressure. When the heart muscle relaxes between contractions (diastole), the blood pressure drops to a lower level, the diastolic blood pressure. When recorded in the patient’s chart, the systolic pressure is recorded first, followed by the diastolic pressure (e.g., 120/80 mm Hg). The difference between the systolic and diastolic pressure is called the pulse pressure, which is an indicator of the tone of the arterial blood vessel walls. The mean arterial pressure (MAP) is the average pressure throughout each cycle of the heartbeat and is significant because it is the pressure that actually pushes the blood through the circulatory system to perfuse organs and tissues. It is calculated by adding one third of the pulse pressure to the diastolic pressure or by using the following equation: Normal MAP readings generally fall between 70 to 110 mm Hg; however, the number 60 or higher has been targeted as enough pressure to adequately perfuse organs and tissues. Under normal conditions, the arterial blood pressure stays within narrow limits. It reaches its peak during high physical or emotional activity and is usually at its lowest level during sleep. Arterial blood pressure (BP) can be defined as the product of cardiac output (CO) and peripheral vascular resistance (PVR): Cardiac output is the primary determinant of systolic pressure; peripheral vascular resistance determines the diastolic pressure. CO is determined by the stroke volume (the volume of blood ejected in a single contraction from the left ventricle), heart rate (controlled by the autonomic nervous system), and venous capacitance (capability of veins to return blood to the heart). Systolic blood pressure is thus increased by factors that increase heart rate or stroke volume. Venous capacitance affects the volume of blood (or preload) that is returned to the heart through the central venous circulation. Venous constriction decreases venous capacitance, increasing preload and systolic pressure, and venous dilation increases venous capacitance and decreases preload and systolic pressure. Peripheral vascular resistance is regulated primarily by contraction and dilation of arterioles. Arteriolar constriction increases peripheral vascular resistance and thus diastolic blood pressure. Other factors that affect vascular resistance include the elasticity of the blood vessel walls and the viscosity of the blood. Hypertension is a disease characterized by an elevation of the systolic blood pressure, the diastolic blood pressure, or both. North American studies have shown that blood pressures above 140/90 mm Hg are associated with premature death, which results from accelerated vascular disease of the brain, heart, and kidneys. Primary hypertension accounts for 90% of all clinical cases of high blood pressure. The cause of primary hypertension is unknown. At present, it is incurable but controllable. It is estimated that more than 75 million people in the United States—or about one-third of the population over age 20—have hypertension. The prevalence increases steadily with obesity and advancing age so that people who are normotensive at age 55 have a 90% lifetime risk of developing hypertension. In every age group, the incidence of hypertension is higher for African Americans than whites of both genders. Other major risk factors associated with high blood pressure are listed in Box 23-1. Secondary hypertension occurs after the development of another disorder within the body (Box 23-2). The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure 2003 (JNC 7) has classified blood pressure by stages that represent the degree of risk of nonfatal and fatal cardiovascular disease events and renal disease (Table 23-1). The category of “prehypertension” was added to the classification system in the 2003 report because of the very high likelihood of people with a blood pressure in this range of having a heart attack, heart failure, stroke, and/or kidney disease. People with blood pressure in this range are in need of increased education and lifestyle modification to gain control of their blood pressure to prevent cardiovascular disease. Table 23-1 Classification and Management of Blood Pressure (BP) for Adults* *Treatment determined by highest BP category. †Treat patients with chronic kidney disease or diabetes to BP goal of <130/80 mm Hg. ‡Initial combined therapy should be used cautiously in those at risk for orthostatic hypotension. Data from the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7), Bethesda, Md., National Institutes of Health Publication No. 03-5233, May 2003, National Institutes of Health. The JNC 7 guidelines consider an elevation in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings when making a diagnosis of hypertension. The individual should be seated quietly for at least 5 minutes in a chair (rather than an examination table), with feet on the floor and arm supported at heart level. An appropriately sized cuff (cuff bladder encircling at least 80% of the arm) should be used for accuracy. A person must have two or more elevated readings on two or more separate occasions after initial screening to be classified as having hypertension. When systolic and diastolic readings fall into two different stages, the higher of the two stages is used to classify the degree of hypertension present. Table 23-2 lists follow-up recommendations based on the initial set of blood pressure measurements. Measurement of blood pressure in the standing position is indicated periodically, especially for those at risk for postural hypotension. Table 23-2 Recommended Follow-Up Schedule after Initial Blood Pressure Measurement *If systolic and diastolic categories are different, follow recommendations for shorter time follow-up (e.g., 160/86 mm Hg should be evaluated or referred to source of care within 1 month). †Modify the scheduling of follow-up according to reliable information about past blood pressure measurements, other cardiovascular risk factors, or target organ disease. In 2003, the Coordinating Committee of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program updated the JNC 7 guidelines and urged health practitioners to use the systolic blood pressure as the major criterion for the diagnosis and management of hypertension in middle-aged and older Americans. Prior to this time, the diastolic blood pressure had been the major determinant for the control of blood pressure. Recent evidence indicates that systolic hypertension is the most common form of hypertension and is present in about two thirds of hypertensive individuals older than 60 years. When a person has been diagnosed with hypertension, further evaluation through medical history, physical examination, and laboratory tests should be completed to (1) identify causes of the high blood pressure, (2) assess the presence or absence of target organ damage and cardiovascular disease (see Box 23-1), and (3) identify other cardiovascular risk factors that may guide treatment (see Table 23-1). The primary purpose for controlling hypertension is to reduce the frequency of cardiovascular disease (angina, myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, renal failure, retinopathy). To accomplish this goal, the blood pressure must be reduced and maintained below 140/90 mm Hg, if possible. Patients who also have conditions such as diabetes mellitus or renal disease should have a goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg. The goal for patients with concurrent heart failure is 120/80 mm Hg. Major lifestyle modifications shown to lower blood pressure include weight reduction in those who are overweight or obese, adoption of the DASH (dietary approaches to stop hypertension) diet, dietary sodium reduction, physical activity, and moderation of alcohol consumption (Table 23-3). Treatment schedules should interfere as little as possible with the patient’s lifestyle; however, nonpharmacologic therapy must include elimination of smoking, weight control, routine activity, restriction of alcohol intake, stress reduction, a regular sleep pattern of at least 7 hours each night, and sodium control. If this therapy is successful in controlling high blood pressure, drug therapy is not necessary. Even if lifestyle changes are not adequate to control hypertension, they may reduce the number and doses of antihypertensive medications needed to manage the condition. Table 23-3 Lifestyle Modifications to Manage Hypertension* The effects of implementing these modifications are dose and time dependent and could be greater for some individuals. *For overall cardiovascular risk reduction, stop smoking. From the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7), Bethesda, Md., National Institutes of Health Publication No. 03-5233, May 2003, National Institutes of Health. Patient education is vitally important in treating hypertension. This education should be emphasized and reiterated frequently by the physician, pharmacist, and nurse. Drugs used in the treatment of hypertension can be subdivided into several categories of therapeutic agents based on site of action (Figure 23-1). Pharmacologic classes of agents used to treat hypertension are: diuretics, beta-adrenergic blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARBs), calcium channel blockers, direct renin inhibitor, aldosterone receptor antagonists, and alpha-1 adrenergic blockers. Less frequently used agents are the central-acting alpha-2 agonists, and direct vasodilators. Agents may be used alone or in combination with agents from different classes working by different mechanisms to optimize therapy while reducing adverse effects of the medicines. A key to long-term success with antihypertensive therapy is to individualize therapy for a patient based on demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, race), coexisting diseases and risk factors (e.g., migraine headaches, dysrhythmias, angina, diabetes mellitus), previous therapy (what has or has not worked in the past), concurrent drug therapy for other illnesses, and cost. As outlined in Figure 23-2, the JNC 7 recommends that if lifestyle modifications do not lower blood pressure adequately for patients with stage 1 or 2 hypertension, a diuretic or an alternative agent should be the initial treatment of choice. A low dose should be selected to protect the patient from adverse effects, although it may not immediately control the blood pressure. It must be recognized that it may take months to control hypertension adequately while avoiding adverse effects of therapy. Due to many physiologic compensatory mechanisms that may aggravate lowering blood pressure, about 75% of hypertensive patients require a combination of medications that act by different pathways to achieve blood pressure goals; (<140/90 mm Hg, or <130/80 mm Hg for patients who have diabetes or chronic kidney disease). If, after 1 to 3 months, the first drug is not effective, the dosage may be increased, another agent from another class may be substituted, or a second drug from another class with a different mechanism of action may be added (Figure 23-3). The guidelines also recommend that if the first drug started was not a diuretic, a diuretic should be initiated as the second drug, if needed, because most patients will respond to a two-drug regimen if it includes a diuretic. After blood pressure is reduced to the goal level and maintenance doses of medicines are stabilized, it may be appropriate to change a patient’s medication to a combination antihypertensive product to simplify the regimen and enhance compliance. See Table 23-4 for a list of the ingredients of antihypertensive combination products. Table 23-4 Combination Drugs for Hypertension *Some drug combinations are available in multiple fixed doses. Each drug dose is reported in milligrams. From the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7), Bethesda, Md., National Institutes of Health Publication No. 03-5233, May 2003, National Institutes of Health. Patients with stage 2 hypertension may require more aggressive therapy, with a second or third agent added if control is not achieved by monotherapy in a relatively short time. Patients with an average diastolic blood pressure higher than 120 mm Hg require immediate therapy and, if significant organ damage is present, may require hospitalization for initial control. The guidelines also provide recommendations for specific groups of patients. For example, older patients with isolated systolic hypertension should first be treated with diuretics with or without a beta blocker, or a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker alone. Patients with high blood pressure, diabetes, hyperlipidemia and/or chronic kidney disease should be treated with the ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Patients who have hypertension and have suffered a myocardial infarction should be treated with a beta-adrenergic blocking agent and, in most cases, an ACE inhibitor. Other studies have demonstrated that if a patient has heart failure, a diuretic, an ACE inhibitor, and an aldosterone receptor antagonist (e.g., spironolactone, eplerenone) may be beneficial. If a patient has angina pectoris, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (e.g., amlodipine, nifedipine) may be added to other therapy because they have been proven to relieve chest pain and reduce the incidence of stroke. Other combinations of therapy found to be particularly effective are an ACE inhibitor plus a diuretic or calcium channel blocker or an ARB plus a diuretic. See individual drug monographs for mechanisms of action of each class of antihypertensive agent. Patients who have modified their lifestyles with appropriate exercise, diet, weight reduction, and control of hypertension for at least 1 year may be candidates for step-down therapy. The dosage of antihypertensive medications may be gradually reduced in a slow, deliberate manner. Most patients may still require some therapy but occasionally the medicine can be discontinued. Patients whose drugs have been discontinued should have regular follow-up examination because blood pressure often rises again to hypertensive levels, sometimes months or years later, especially if lifestyle modifications are not continued. History of Risk Factors Smoking. Obtain a history of the number of cigarettes or cigars smoked daily. How long has the person smoked? Has the person ever tried to stop smoking? Ask whether the person knows what effect smoking has on the vascular system. How does the individual feel about modifying the smoking habit? Dietary Habits. Obtain a dietary history. Ask specific questions to obtain data relating to the amount of salt used in cooking and at the table, as well as foods eaten that are high in fat, cholesterol, refined carbohydrates, and sodium. Using a calorie counter, ask the person to estimate the number of calories eaten daily. How much meat, fish, and poultry are eaten daily (size and number of servings)? Estimate the percentage of total daily calories provided by fats. Discuss food preparation (e.g., baked, broiled, fried foods). How many servings of fruits and vegetables are eaten daily? What types of oils or fats are used in food preparation? See a nutrition text for further dietary history questions. What is the frequency and volume of alcoholic beverages consumed? Elevated Serum Lipids. Ask whether the patient is aware of having elevated lipid, triglyceride, or cholesterol levels. If elevated, what measures has the person tried for reduction and what effect have the interventions had on the blood levels at subsequent examinations? Review laboratory data available (e.g., cholesterol, triglyceride, low-density lipoprotein [LDL], very low-density lipoprotein [VLDL] levels). Renal Function. Has the patient had any laboratory tests to evaluate renal function (e.g., urinalysis—microalbuminuria, proteinuria, microscopic hematuria) or had a blood analysis showing an elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN) or serum creatinine level? Does the patient have nocturia? Obesity. Weigh and measure the patient. Measure the waist circumference 2 inches above the navel. Ask about any recent weight gains or losses and whether intentional or unintentional. Note abnormal waist-to-hip ratio. Patients with more weight around their waist have a higher incidence of developing heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes (see Chapter 21). Psychomotor Functions Medication History Physical Assessments Blood Pressure. Obtain two or more blood pressure measurements. Height and Weight. Weigh and measure the patient. What has the person’s weight been? Ask about any recent weight gains or losses and whether intentional or unintentional. Calculate the body mass index (BMI) (see Chapter 21 for more discussion and classification of BMI). Bruits. Check neck, abdomen, and extremities for the presence of bruits. Peripheral Pulses. Palpate and record femoral, popliteal, and pedal pulses bilaterally. Eyes. As appropriate to the level of education, perform a funduscopic examination of the interior eye, noting arteriovenous nicking, hemorrhages, exudates, or papilledema. • Examine data to determine the individual’s extent of understanding of hypertension and its control. Baseline and Diagnostic Studies. Review the chart and reports available that are used to build baseline information (e.g., electrocardiogram; urinalysis; blood glucose, hematocrit, serum potassium, BUN, creatinine, and calcium levels; a lipid profile [total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides] after a 9- to 12-hour fast). Smoking. Suggest that the patient stop smoking. Provide educational materials for smoking cessation Explain the increased risk of coronary artery disease if the habit is continued. It may be necessary to settle for a drastic decrease in smoking in some people, although abstinence should be the goal. Nutritional Status • Dietary counseling is essential for the treatment of hypertension. Control of obesity alone may be sufficient to alter the hypertensive condition. Most patients are placed on a reduced-sodium diet (2.3 g sodium or <6 g table salt per day). The goal of dietary therapy is a reduction of cholesterol, lipids, saturated fat, and alcohol consumption. Foods high in potassium and calcium are encouraged to decrease blood pressure. See the DASH diet for further information (see Table 23-3). Stress Management Exercise and Activity. Develop a plan for moderate exercise to improve the patient’s general condition. Consult the health care provider for any individual modifications deemed appropriate. Suggest including activities that the patient finds helpful in reducing stress. Nurses can help patients increase physical activity throughout the day by encouraging them to take part in the following: Blood Pressure Monitoring. Demonstrate the correct procedure for taking blood pressure. It is best to have the patient or family bring in the blood pressure equipment that will be used at home to perform the blood pressure measurement. Validate the patient’s and family’s understanding by having them perform this task on several occasions under supervision. Monitor blood pressure, pulse, and respirations at least every shift while hospitalized and on discharge in accordance with the health care provider’s orders, usually daily. The patient should be given some numeric guidelines, as established by the health care provider, for a desired goal of therapy and what to do if this is not being achieved. Normal home blood pressure should at least be lower than 137/85 mm Hg. Nighttime home blood pressure is usually lower than daytime pressure. Medication Regimen Fostering Health Maintenance Written Record. Enlist the patient’s aid in developing and maintaining a written record of monitoring parameters (e.g., blood pressures, weight, exercise; see Patient Self-Assessment Form for Cardiovascular Agents on the Evolve website). The diuretics act as antihypertensive agents by causing volume depletion, sodium excretion, and vasodilation of peripheral arterioles. The mechanism of peripheral arteriolar vasodilation is unknown. There are four classes of diuretic agents: carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, thiazide and thiazide-like agents, loop diuretics, and potassium-sparing diuretics (see Chapter 29). The carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are weak antihypertensive agents and therefore are not used for this purpose. The potassium-sparing diuretics are rarely used alone but are commonly used in combination with thiazide and loop diuretics for added antihypertensive effect and to counteract the potassium-excreting effects of these more potent diuretic-antihypertensive agents. The diuretics are the most commonly prescribed antihypertensive agents because they are a class of agents that have been shown to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with hypertension. The thiazides are most effective if the renal creatinine clearance is higher than 30 mL/min; however, as renal function deteriorates, the more potent loop diuretics are needed to continue excretion of sodium and water. Diuretics are also commonly prescribed in combination therapy. They potentiate the hypotensive activity of the nondiuretic antihypertensive agents, have a low incidence of adverse effects, and are often the least expensive of the antihypertensive agents. Diuretics are used (often with other classes of antihypertensive therapy) to treat all stages of hypertension. The agents are discussed more extensively in Chapter 29.

Drugs Used to Treat Hypertension

Objectives

Key Terms

) (p. 357)

) (p. 357)

) (p. 357)

) (p. 357)

) (p. 357)

) (p. 357)

) (p. 357)

) (p. 357)

) (p. 357)

) (p. 357)

) (p. 357)

) (p. 357)

) (p. 358)

) (p. 358)

) (p. 358)

) (p. 358)

) (p. 358)

) (p. 358)

Hypertension

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

BLOOD PRESSURE (mm Hg)

INITIAL DRUG THERAPY

BP CLASSIFICATION

SYSTOLIC

DIASTOLIC

LIFESTYLE MODIFICATION

WITHOUT COMPELLING INDICATION

WITH COMPELLING INDICATION

Normal

<120

and

<80

Encourage

No antihypertensive drug indicated

Drug(s) for compelling indications

Prehypertension

120-139

or

80-89

Yes

No antihypertensive drug indicated

Drug(s) for compelling indications†

Stage 1 hypertension

140-159

or

90-99

Yes

Thiazide-type diuretics for most; may consider ACEI, ARB, BB, CCB, or combination

Drug(s) for compelling indications†

Other antihypertensive drugs (diuretics, ACEI, ARB, BB, CCB) as needed

Stage 2 hypertension

≥160

or

≥100

Yes

Two-drug combination for most‡ (usually thiazide-type diuretic and ACEI or ARB, BB, CCB)

Drug(s) for compelling indications

Other antihypertensive drugs (diuretics, ACEI, ARB, BB, CCB) as needed

INITIAL BLOOD PRESSURE (mm Hg)*

SYSTOLIC

DIASTOLIC

FOLLOW-UP RECOMMENDED†

<130

<85

Recheck in 2 yr

130-139

85-89

Recheck in 1 yr‡

140-159

90-99

Confirm within 2 mo‡

160-179

100-109

Evaluate or refer to source of care within 1 mo

≥180

≥110

Evaluate or refer to source of care immediately or within 1 wk, depending on clinical situation

Treatment of Hypertension

MODIFICATION

RECOMMENDATION

APPROXIMATE SYSTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE REDUCTION (RANGE)

Weight reduction

Maintain normal body weight (body mass index 18.5-24.9 kg/m2).

5-20 mm Hg/10-kg weight loss

Adopt DASH eating plan

Consume a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products with a reduced content of saturated and total fat.

8-14 mm Hg

Dietary sodium reduction

Reduce dietary sodium intake to no more than 100 mmol per day (2.4 g sodium or 6 g sodium chloride).

2-8 mm Hg

Physical activity

Engage in regular aerobic physical activity such as brisk walking (at least 30 min/day, most days of the week).

4-9 mm Hg

Moderation of alcohol consumption

Limit consumption to no more than two drinks (1 oz or 30 mL ethanol [e.g., 24 oz beer, 10 oz wine, or 3 oz 80-proof whiskey])/day in most men and no more than one drink/day in women and lighter weight persons.

2-4 mm Hg

DASH, dietary approaches to stop hypertension.

Drug Therapy for Hypertension

Actions

Uses

COMBINATION TYPE

FIXED-DOSE COMBINATION (mg)*

TRADE NAME

ACEIs and CCBs

amlodipine/benazepril hydrochloride (2.5/10, 5/10, 5/20, 5/40, 10/20, 10/20)

Lotrel

enalapril maleate/felodipine (5/2.5, 5/5)

Lexxel

trandolapril/verapamil (2/180, 1/240, 2/240, 4/240)

Tarka

CCBs and statin

amlodipine/atorvastatin (2.5/10 to 10/80)

Caduet

CCBs and ARBs

amlodipine/valsartan (5/160 to 10/320)

Exforge

amlodipine/olmesartan (5/20 to 10/40)

Azor

ACEIs and diuretics

benazepril/hydrochlorothiazide (5/6.25, 10/12.5, 20/12.5, 20/25)

Lotensin HCT

captopril/hydrochlorothiazide (25/15, 25/25, 50/15, 50/25)

Capozide

enalapril maleate/hydrochlorothiazide (5/12.5, 10/25)

Vaseretic

lisinopril/hydrochlorothiazide (10/12.5, 20/12.5, 20/25)

Prinzide ![]() Do not confuse Prinzide with Prinivil.

Do not confuse Prinzide with Prinivil.

moexipril HCl/hydrochlorothiazide (7.5/12.5, 15/12.5, 15/25)

Uniretic

quinapril HCl/hydrochlorothiazide (10/12.5, 20/12.5, 20/25)

Accuretic

ARBs and diuretics

candesartan cilexetil/hydrochlorothiazide (16/12.5, 32/12.5, 32/25)

Atacand HCT

eprosartan mesylate/hydrochlorothiazide (600/12.5, 600/25)

Teveten/HCT

irbesartan/hydrochlorothiazide (150/12.5, 300/12.5, 300/25)

Avalide

losartan/potassium/hydrochlorothiazide (50/12.5, 100/12.5, 100/25)

Hyzaar ![]() Do not confuse Hyzaar with Cozaar.

Do not confuse Hyzaar with Cozaar.

olmesartan/hydrochlorothiazide (20/12.5, 40/12.5, 40/25)

Benicar HCT

telmisartan/hydrochlorothiazide (40/12.5, 80/12.5, 80/25)

Micardis/HCT

valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide (80/12.5, 160/12.5, 320/12.5, 160/25, 320/25)

Diovan/HCT

BBs and diuretics

atenolol/chlorthalidone (50/25, 100/25)

Tenoretic

bisoprolol fumarate/hydrochlorothiazide (2.5/6.25, 5/6.25, 10/6.25)

Ziac ![]() Do not confuse Ziac with Zocor or Tiazac.

Do not confuse Ziac with Zocor or Tiazac.

propranolol LA/hydrochlorothiazide (40/25)

metoprolol tartrate/hydrochlorothiazide (50/25, 100/25, 100/50)

Lopressor HCT

nadolol/bendroflumethiazide (40/5, 80/5)

Corzide

Direct renin inhibitor combination products

Aliskiren/amlodipine (150/5, 150/10, 300/5, 300/10)

Tekamlo

Aliskiren/amlodipine/hydrochlorothiazide (150/5/12.5, 300/5/12.5, 300/5/25, 300/10/12.5, 300/10/25)

Amturnide

Aliskiren/valsartan (150/160, 300/320)

Valturna

Diuretic and diuretic combination

amiloride HCl/hydrochlorothiazide (5/50)

Moduretic

spironolactone/hydrochlorothiazide (25/25, 50/50)

Aldactazide

triamterene/hydrochlorothiazide (37.5/25, 50/25, 75/50)

Dyazide, Maxzide

![]() Nursing Implications for Hypertensive Therapy

Nursing Implications for Hypertensive Therapy

Assessment

Implementation

![]() Patient Education and Health Promotion

Patient Education and Health Promotion

![]() Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient understands how to use the form and instruct the patient to bring the completed form to follow-up visits. During follow-up visits, focus on issues that will foster adherence with the therapeutic interventions prescribed.

Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient understands how to use the form and instruct the patient to bring the completed form to follow-up visits. During follow-up visits, focus on issues that will foster adherence with the therapeutic interventions prescribed.

Drug Class: Diuretics

Actions

Uses

![]() Nursing Implications for Diuretic Agents

Nursing Implications for Diuretic Agents

Premedication Assessment

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

23. Drugs Used to Treat Hypertension

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree