CHAPTER 23. Connecting clinical and theoretical knowledge for practice

Jane Conway and Margaret McMillan

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

• appreciate the interaction between clinical practice and classroom-based learning activities

• identify strategies that maximise learning opportunities in a range of contexts

• explore strategies for acquiring knowledge-ABILITY

• view themselves as autonomous, action-oriented learners

• appreciate the interaction between lifelong learning and professional development, and

THE CLINICAL AREA: THE SITE OF NURSING PRACTICE

A confident, competent nursing workforce that has the capacity to provide comprehensive, person-centred care and is part of a cohesive, interprofessional healthcare team is dependent upon the effective transition from being a student to a recent graduate who makes connections between clinical and theoretical knowledge. The curriculum underpinning a nursing program focuses on educating students for clinical practice and uses educational strategies that support the integration of clinical and theoretical knowledge.

Nursing programs globally recognise that the clinical area is an important, if not the most important, area for practice professions such as nursing (Campbell, 2003 and Lambert, 2005). Definitions of clinical teaching and learning invariably include some notion that clinical practice is the place where students apply theory in practice, or where contradictions between theory and practice, and nursing and educational values, are highlighted (Campbell 2003). The clinical environment is, in fact, where students begin to develop professional identities as nurses, but it is only the beginning of the pathway to personal confidence and competence. This pathway continues throughout the postgraduate transition year and beyond (Newton & McKenna 2007).

Individuals, employers, supervisors, education bodies and regulatory authorities have a collective responsibility to ensure that the knowledge and skills base from which a nurse operates is not only extensive enough for the roles and functions of a given position, but is also up-to-date, within the law and directed towards client benefit. This provides a series of safeguards, enhances risk management and contributes to quality improvement through promoting application of the principles of ethics, which include doing good, not doing harm, justice and autonomy.

Clinical practice provides the stimulus for students and practitioners alike to use these skills in order to recognise best practice and, if necessary, enhance and modify existing practice. This chapter is designed to encourage students to view clinical and on-campus learning as one entity—a continuum of development and lifelong learning that has the unifying goal of achieving and maintaining competence within the complexities of contemporary practice.

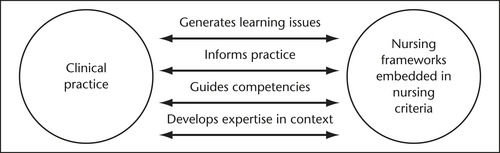

Figure 23.1 depicts the interrelationship between clinical practice knowledge and the theoretical knowledge embedded in nursing-specific frameworks within nursing curricula. This diagram indicates that clinical activity and on-campus learning are interdependent.

The curriculum provides formal structure to a student’s learning. However, beyond graduation, nurses are able to create their own curriculum by framing work experiences as learning experiences and drawing upon their abilities as lifelong learners, reflective practitioners and information-literate graduates who appreciate the importance of continuing professional development for fulfilment of the competency standards for nursing practice.

The transition from student to graduate provides an opportunity to launch a career in nursing. This requires the development of the ability to critically examine one’s own and others’ practice and be accountable for individual action. These abilities are often linked to the idea of being a lifelong learner (Department of Health, 2001 and National Review of Nursing Education, 2002), and are seen as increasingly important to professional nursing practice in the twenty-first century.

The changing nature of health service delivery continues to present challenges to both clinicians and students. In literature related to contemporary health service delivery, it is widely acknowledged that reduced average lengths of stay, an ageing clientele, increased throughput and acuity, developments in healthcare and educational technology, and increasing numbers of learners requiring clinical experience, impact on the clinical learning milieu and the extent to which it consistently fosters the cognitive skills required for professional practice (Jeffries, 2008, Lunney, 2008 and McMillan and Conway, 2004). It is imperative that learners capitalise on events in both clinical and on-campus settings that foster their ability to critically analyse situations, identify underpinning knowledge and ideas, and critically appraise their own professional development. Such critique needs to be managed carefully in order to maintain perspective and avoid overreaction.

Over decades, much has been written about the impact of a purported reality shock that students experience during clinical experience and/or upon entry into the workforce as a graduate. The transition period from graduate to practitioner has been seen as a time during which nurses are socialised into the workplace and its formal and informal rules, protocols, norms and expectations. It has been identified as an exciting, challenging and stressful period (Chang & Hancock 2003). A range of factors contribute to a sense of reality shock, including the need to adjust to the demands of shift work, time pressures associated with assuming a case load, coping with workplace staff shortages, experiencing potential intergenerational differences in work values and ethics, and the need to accept accountability for patient safety and to delegate to and supervise other staff. Etheridge (2007) has reported that new graduates experience a lack of confidence in their interpretation of assessment data and clinical decision making.

The transition from student to graduate has been likened to a grieving response (Halfer & Graf 2006) and is a period whereby the graduate initially focuses (we would say rightly) on themselves and their own development for the first 6 months in the workplace (McKenna & Green 2004). The aspirations of the profession of nursing are for the transition period to be positive and supportive. However, despite these aspirations, new graduates continue to experience fragmentation and frustration as clinical demands conflict with access to support, mentorship and continuing development (Fox and Henderson, 2005 and Moore, 2006).

It is our contention that there is a need to focus on the positive rather than the negative aspects of transition and to acknowledge the extent to which graduates have a repertoire of portable knowledge and skills, which provide a foundation for the development of individual agency as a practitioner. Individual agency is the mechanism that enables knowledge-ABILITY through continuing development of self-insight, a sense of self-efficacy and recognition of the need for self-determination. It is associated with moving beyond the initial and natural sense of alienation experienced in an unfamiliar context to a sense of self-confidence, composure and resilience. Development of self-agency is an iterative rather than lineal process that requires that nurses take responsibility for themselves and their learning. This self-agency requires an ability to create meaning in a given context and to embrace a view of learning as ‘volitional, curiosity-based, discovery-driven, and mentor-assisted’ (Janik 2005:144) and results in the continuing creation and transformation of perspective, through cognitive and affective engagement in reflective practice (Dirkx 2006).

The capacity to respond appropriately and effectively in nursing practice is dependent upon the extent to which we connect clinical and theoretical knowledge in order to make sense of the situations that students engage with during clinical learning experiences and that graduates encounter during their transition. Such sense making requires what we have termed knowledge-ABILITY. The concept of knowledge-ABILITY requires that learners are able to transfer concepts between the learning cultures typical of on-campus and clinical environments. Without clinical learning experiences which provide the opportunity to integrate classroom theory in ‘real-life’ practice situations, nursing students may have had little opportunity to develop the lifelong learning skills of critical thinking and reflective practice considered important to professional practice.

In her often cited, seminal work about the development of registered nurses, Benner (1984) has identified that the ability to integrate theory and practice to the point of being able to generalise is essential to development from novice (newly qualified nurse) to more advanced levels of nurse. However, Benner also acknowledges that there are particular challenges in being able to transfer concepts across clinical contexts. Effective clinicians are aware that context is the crucial moderator in nursing practice, and have developed mechanisms for managing situations contextually, rather than seeking to manage all situations in the same way.

Such ability to transfer core concepts across situations and modify actions according to context is an indication of ‘expert’ nursing practice (Benner 1984). Expanding upon this, we believe there is a need for learners to be able to transfer concepts between the learning cultures typical of on-campus and clinical environments. In the remainder of this chapter, we seek to reinforce to readers that throughout their learning as students, they will acquire a set of knowledge and skills in both nursing and learning that are transferable to a range of contexts and which are foundational for professional practice as a nurse.

CONNECTING CLINICAL AND THEORETICAL LEARNING TO BECOME KNOWLEDGE-ABLE

We recognise that, for many student nurses, clinical practice is the goal of nursing education.

Clinical educators, lecturers and clinicians often declare that they have a shared goal of ensuring quality education for nursing students. However, each of these sectors of the nursing community has what, at times, may seem to be very different definitions of nursing and, within that, different expectations of students and graduates. This results in what students may perceive as a lack of alignment between the values of, and experiences in, the education and health service sectors.

While much of this perceived lack of alignment has been attributed to what students and clinicians may hear described as the theory–practice gap (Howatson-Jones 2003), it is our view that nursing education has a single unifying focus—to assist people to be nurses. Being a nurse requires the ability to actively respond with nursing interventions, to think about the clinical judgments made and the consequences of action taken, and to develop a capacity to articulate that thinking to others.

The principles that underpin learning in the clinical area are used in on-campus learning activities. These are transferable across clinical and theoretical learning contexts.

Contemporary nursing curricula include discipline-specific knowledge, and integration of knowledge from other disciplines to inform the practice of nursing. This differs from previous practices of modifying knowledge from other disciplines to suit nursing situations. Thus, nursing education serves both an epistemological and political purpose, and students should be able to articulate and conceptualise the nature of their discipline and apply their thinking to actual practice.

The overarching structure of all nursing courses is the nursing curriculum, which determines both the outcomes that should be achieved and the processes by which these will be achieved. Nursing education programs include both on-campus and clinical learning experiences, which provide students with opportunities to practise the skills of nursing, to develop and demonstrate their knowledge base about nursing, and to acquire academic skills that support communication of their thinking about nursing. Increasingly, nursing curricula use problem-based teaching strategies to encourage development of the knowledge, skills and behaviours of effective clinicians. This type of learning fosters exploration of ‘real-life’ situations to enhance critical thinking and clinical decision making (Conway & Little 2003).

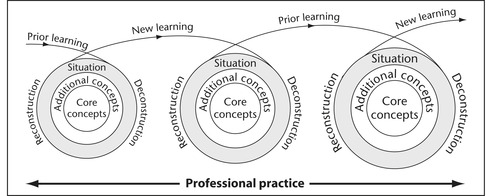

Figure 23.2 demonstrates the continual process of conceptualisation and reconceptualisation of nursing, which occurs through situation deconstruction, analysis and reconstruction. These enquiring and processing skills are essential to professional practice and the development of knowledge.

The curriculum should cause students to think about what they do as nurses, why they do what they do, and how they might do it differently. It is these enquiry skills that will cause the student to generate knowledge about nursing. For this reason, it is important that the nursing curriculum raises questions such as: ‘What is nursing?’ ‘What does it mean to nurse?’ ‘Whom do nurses nurse?’ ‘Where do nurses nurse?’ ‘Is nursing the same as caring?’ and so on, as well as helping students to learn the task-oriented content of how to nurse.

Conceptualising or thinking about nursing needs to both direct and emerge from practice. It is a process of enquiry in which students work with concepts and form networks of concepts that frame and impact on their practice. It is not our intention to give the impression that qualified nurses should only think about nursing. The goal of nursing programs is to develop a graduate who can apply concepts to practice, manage complex nursing situations, and accept accountability for practice. Of course, this also demands skills in doing nursing activities.

However, we believe that students should be aware that nursing is about the ability to analyse situations and respond appropriately. How we interpret and analyse situations depends upon how we think about them. As our thinking about nursing develops, the meaning we give to situations changes and learning occurs. We then take this learning with us to the next situation and create new meanings and experiential knowledge.

Experiential knowledge is not merely being exposed to an experience. It is that which emerges when the experience is structured to achieve learning as an outcome of the experience. Therefore, students should use the theoretical base developed from on-campus, university-based activities to frame the clinical experience so that learning, rather than merely experiencing, occurs. Students should ask themselves: ‘What is it that I want to achieve from this learning experience and how does this relate to my ability to practise nursing?’

Clinical learning experiences provide nursing students with the opportunity to begin to develop the skills of identifying general principles of practice, transferring these across contexts, and modifying actions based on principles of management. While clinical experience clearly is a powerful motivator for students to learn how to nurse, the literature suggests that clinical experiences are an important part of the transfer of learning from the classroom to the practice setting.

How we think about nursing practice shapes what we learn from or about practice and how we direct the transition from student to recent graduate and subsequent movement along a career pathway. However, as noted by Heartfield (2006), there are differing representations or constructions of nursing practice dependent on individual, professional, industrial, regulatory and organisational perspectives. Irrespective of perspective and context, ‘being a nurse’ requires the ability to integrate the knowledge, skills and attitudes of nursing into who we are and how we practise.

Now, more than ever before, contemporary health service delivery demands that nurses demonstrate the full suite of skills representative of the knowledge-ABLE worker. The knowledge-ABLE worker aspires to enhance patient and staff safety, minimise adverse circumstances, promote partnership initiatives, focus on ‘fitness-to-function’ and acknowledge that health service delivery is dependent upon multiprofessional team effort. Thus, the student nurse as a knowledge-ABLE learner sees connections between clinical and theoretical knowledge of nursing within a broader framework of learning that integrates his or her experience and the outcomes of education for a knowledge-ABLE worker.

Table 23.1 presents the elements of contemporary health service challenges and desired knowledge-ABLE worker responses. The table indicates that although the factors that impact on health service delivery and healthcare work can be viewed in isolation, nurses, as knowledge-ABLE workers, require a multifaceted education to respond meaningfully to the challenges in contemporary health service provision.

| Health service challenges | Knowledge-ABLE worker responses |

|---|---|

| Fragmented patient experience/changing health patterns/chronicity and consumerism | Contributors to systems review |

| Technology: increased emphasis on clinical and information systems interface | Effective managers of consumer expectations, competing value systems, and tensions in resource allocation |

| Changing workforce: unaligned skill mix and case mix | Procedurally competent, information fluent personnel |

| Inappropriate structures and process | Coordinators of throughput and care processes |

| Changing professional roles and functions | Participants in networked organisation and healthcare teams |

| Overcoming rigidity in professional frameworks and knowledge bases | Personnel who focus on consumer needs and outcomes, rather than profession-specific outcomes |

HOW TO BEST DEVELOP KNOWLEDGE-ABILITY

Classroom-based learning activity provides us with a relatively safe environment to explore what we know, what we do and who we are as nurses, so that we are more prepared for professional practice situations. Clinical learning activity provides us with the opportunity both to test out what we have learnt in practice and to confront new situations from which we can further our learning. However, we can only learn if we are prepared to do so. It is important that we value learning as much as we value what we have learnt. It is our ability to question ourselves and our practice that enhances our professional development.

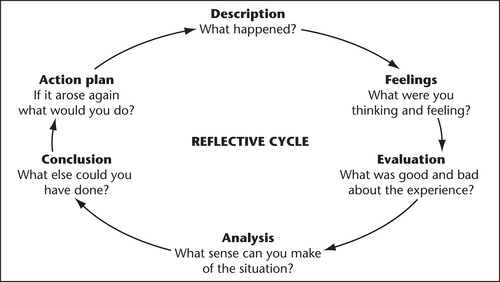

In order to learn we need to develop the process skills for lifelong learning (Armstrong et al.,2003, Griffitts, 2002 and Maslin-Prothero, 2001). These process skills are the basis of learning and are transferable across disciplines. In the case of nursing, nursing knowledge provides specific content which, when processed, results in nursing action. That is to say, when we become nurses we have developed general learning skills and we demonstrate our use of these through being able to ‘think and act like a nurse’. In order to be lifelong learners in relation to nursing practice, we need to become what has been termed ‘reflective practitioners’ (Johns 2000). We need to reflect about what we do as nurses, how we respond as nurses and individuals, and what we would do again in a similar situation. We then need to act when a similar situation occurs. The skills of reflective practice unite theoretical and clinical concepts; are both thought-oriented and action-oriented; allow for consideration of the affective aspects of nursing experience, and provide opportunity to explore how the learner as a reflective practitioner felt about the experience. Such an approach is particularly useful in nursing, as it acknowledges human and emotional, as well as intellectual, domains of decision making and encourages self-regulation and autonomy in learning (Morgan and Rawlinson, 2006 and Zimmerman, 2000).

In Figure 23.3, Gibbs (1988) provides a useful framework for situation analysis that is both thought-oriented and action-oriented, and allows for consideration of the affective aspects of nursing experience and provides opportunity to explore how the learner as a reflective practitioner felt about an experience.

|

| Figure 23.3 Source: Gibbs G 1988 Learning by doing: a guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit, Oxford Polytechnic, Oxford.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|