CHAPTER 22. Using informatics to expand awareness∗

Moya Conrick and Anthony C. Smith

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

• articulate and discuss the major concepts underpinning informatics

• critically reflect on informatics as a tool of nursing practice

• assess and critically reflect on the automation of nursing and health data

• critically evaluate the infostructure requirements for nursing information systems, and

• appreciate the importance of knowledge management in nursing at a beginning level.

NURSING AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

The health industry faces many challenges—because the health sector is complex and fragmented, involves multiple levels of government, numerous individuals and a large number of private sector organisations. Health services are becoming more expensive, and the demand on health services is growing due to factors such as the ageing population, the increasing burden of chronic disease, and the costs of new methods of diagnosis and treatment (Armstrong et al., 2007 and Conrick, 2006).

In a report by the Australian Department of Finance and Administration (2006), national spending on information and communication technology (ICT) is about $5 billion a year, while ICT expenditure in the Australian healthcare industry is estimated at $2 billion per year, which seems to be an indication by government policy makers that ICT is a useful resource in efforts to improve patient care and deliver quality health outcomes (Conrick et al 2004). Automation has much to offer healthcare workers and, indeed, the last ten years have seen the beginnings of a transformation in healthcare, triggered by a rapid rise in the use of information technology across all areas of healthcare and the rapid increase in the sophistication of information systems. While health administration was an early adopter of information technology, and new technology for diagnostic and treatment purposes is becoming commonplace, investment in systems and strategies to support clinicians lags well behind. Clinicians usually have to navigate myriad paperwork and often make decisions based on fragmented and poor-quality data.

There is potential for information technology to be used for the storage and delivery of health information, especially between clinicians, which in turn may contribute to better patient outcomes and reduction in errors, by delivering timely clinical information quickly and at the point-of-care in a form that can be read and understood. It also empowers clinicians by providing them with the tools of evidence-based decision making, with the deployment of knowledge databases and information repositories. Leonard et al (2004) suggest that information technology has the ability to address the communication failures that account for approximately 70% of causes of sentinel events reported to the Joint Commission for Hospital Accreditation. In retrospect, however, caution should be taken with the use of ICT, as some reports have emerged which suggest that the risk of errors (such as in medication prescribing) could increase in some circumstances due to inaccurate data entry (Magrabi et al 2007).

Information technology eases the burden of gathering and manipulating large amounts of data and can reduce repetition. Provided that appropriate protocols and standards are in place, computers manipulate complex data quickly and are able to communicate seamlessly across the health system. This supports the efficient collection and sharing of comprehensive, quality health information that can be used to improve the delivery of health services across populations. One only has to look at the changes in communications since the development of the internet to realise that information technology has permanently transformed the way in which we communicate. A simple example is that of the telephone with alpha designations, which allow short message services (SMS) to be sent to other telephones. Communication via SMS has become so widespread it is estimated around 10 billion messages are sent each year in Australia.

The benefits of SMS in the healthcare sector are very promising. In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service sends routine SMS to patients to make them aware of visits, follow-up or changes to appointments. According to work reported in Australia by Downer et al (2005), SMS reminders sent to patients prior to their scheduled outpatient appointment has a similar impact to standard telephone reminders, but was much more economical due to the ability to send large volumes of customised messages in one instance.

This chapter expands health professionals’ awareness of informatics as a tool for clinical practice and discusses the major issues for nursing in its uptake. It will expand readers’ awareness of the use of technology in the collection, use and sharing of digitised health information. There are many branches of health informatics, but it is predominantly nursing informatics that will be perused in this chapter. In such a complex discipline, it is not surprising for confusion in nomenclature to arise and it is pertinent here to discuss the common terms of e-health and health informatics.

HEALTH INFORMATICS OR E-HEALTH

The term nursing informatics was introduced into the nursing profession in the late 1980s in alliance with the many technical advances that have been reported to date. Among the definitions, a widely accepted definition is that of the Nursing Informatics Specialist Group of the International Medical Informatics Association (IMIA–NI). According to the IMIA–NI, nursing informatics is ‘the integration of nursing, its information, and information management with information processing and communication technology, to support the health of people world-wide’ (Conrick 2006:5). Other terms that are also sometimes associated with informatics but are used to describe the use of communication technology in healthcare are telemedicine, telehealth and e-health.

Telemedicine refers to the delivery of ‘medical’ services across a distance using a range of communication techniques, such as telephone, email and videoconferencing (Smith 2007). With recent advances in all areas of healthcare, including medical, nursing and allied health, a more general term ‘telehealth’ has often been adopted (see Ch 16). Despite this, there are always new terms being introduced that are often a cause for confusion. The introduction of yet another term (i.e. ‘e-health’) seemed to be in response to the growth of internet (web-based) services and exploitation of information technology in the healthcare sector.

‘E-health’ is defined by the World Health Organization (2008) as the use, in the health sector, of digital data—transmitted, stored and retrieved electronically— in support of healthcare, both at the local site and at a distance. It refers to the healthcare components delivered, enabled or supported through the use of information and communications technology. Examples include clinical communication systems such as online referrals, e-prescribing and electronic health records. E-health is identified as a platform for remote health service delivery, patient-centred care, supported self-care, remote access and monitoring, and health system sustainability.

Health informatics is an evolving sociotechnical and scientific discipline that deals with the collection, storage, retrieval, communication and optimal use of health-related data, information and knowledge. The discipline utilises the methods and technologies of the information sciences for the purposes of problem solving and decision making—thus, assuring quality healthcare in all basic and applied areas of biomedical sciences for the community it serves (Health Informatics Society of Australia 2007).

In healthcare, the use of information technology has caused some debate, some of which has been quite passionate. In time, we suspect that parallels will be drawn with the following quote, and healthcare workers might then wonder what the fuss was all about:

That it will ever come into general use, notwithstanding its value, is extremely doubtful because its beneficial application requires much more time and gives a good bit of trouble, both to the patient and to the practitioner because its hue and character are foreign and opposed to all our habits and associations (The London Times, 1834, commenting on the stethoscope).

INFORMATICS AS A TOOL FOR NURSING

Nurses focus on patients’ responses to illness, injury, treatment and care within the context of the patients’ family, social structure and location (Conrick et al 2004). In addition, their services are guided by patient risk assessments, which form the basis of preventative nursing interventions. These assessments and interventions include the broader health context of psychosocial, environmental and family/carer considerations, and are crucial to the ongoing health of our community. Nurses are the only professionals who work across health transitions and therefore the continuum-of-care. To effectively and efficiently engage with patients and clients across such diverse practice areas, nurses must use the most efficient and effective tools available to them, and technology is able to provide many of these.

Nurses are found in a diversity of practice areas and geographical settings supporting an increasingly transient community. This is an increasing challenge, particularly in rural and remote Australia, where they (nurses) are often isolated from other practitioners and must, by necessity, practise alone. The fragmented records of care and inadequate methods of communication are a major issue. Information technology has the potential to support clinicians by providing timely, quality data, and to largely negate the tyranny of distance, through high-speed broadband and satellite access. This is the domain of nursing informatics.

Nursing informatics may be defined as:

… a specialty area that integrates nursing science, computer science, and information science to manage and communicate data, information and knowledge in nursing practice settings. It facilitates the integration of data, information and knowledge to support patients, nurses and other providers in their decision-making in all roles and settings, by using information structures, information processes, and information technology (Staggers & Thompson 2002:262).

As information technology permeates nursing, all nurses must have a working knowledge of informatics and understand what it offers the profession. Nursing input is essential in the development of information systems, and anecdotal evidence suggests that it is a significant factor in the success or failure of these systems.

GATHERING EVIDENCE TO AID DECISION MAKING

It is crucial that robust and relevant electronic data are collected for use in clinical practice and professional collaboration, because these data are the basis for decision making and evidence-based practice in the healthcare sector. In informatics terms, the gathering of evidence for decision making actually begins with the most basic of language building blocks—that is, data.

The International Standards Organization defines data as the representation of real-world facts, concepts or instructions in a formalised manner suitable for communication, interpretation or processing by human beings or by automatic means (International Standards Organization 1999). Information builds on data and is the output of the data interpretation, organisation and structure (Standards Australia 2003). When information has been synthesised, interrelationships are identified and formalised knowledge is created (Standards Australia 2003). The evidence for use as clinical information and nursing knowledge result from the progressive cognitive or automated processing and manipulation of data, language and knowledge, and in turn governs it. Nurses are recognised as the key collectors, generators and users of patient/client data and information, and the delivery of good nursing care is dependent upon the quality and timeliness of the information available (Currell et al., 2002 and Hovenga and Hindmarsh, 1996a).

THE COLLECTION OF DIGITISED HEALTH INFORMATION

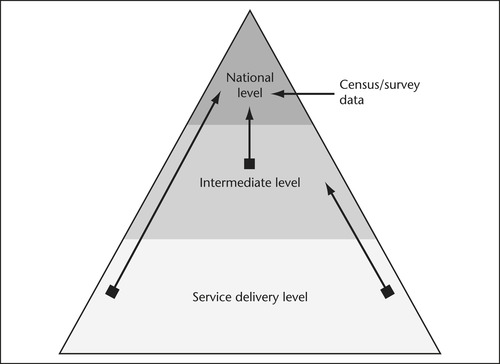

According to Mercer (2003), there are three levels at which the collection of digitised health information can be used and shared. The first level is the service delivery level and most data are generated here (see Fig 22.1). At this level, computer systems capture initial patient care data, but may also exchange data between different systems (e.g. a referral could be generated from the hospital to a community service or from one program to another). Data from this level also form the basis of population surveys. National standards operate here to ensure quality and clean data collection. Mercer describes the second level as the intermediate level, saying that:

|

| Figure 22.1 Source: Based on Mercer N 2003 Redevelopment of the AIHW knowledgebase—stage 1: scope and issues paper. AIHW, Canberra. |

… data from the lowest level of the pyramid are often required to be reported, perhaps within a service delivery outlet (total activity counts for a day), or to a regional or area agency or authority (total activity counts for a week, or agency expenditure totals for a financial year) (Mercer 2003:16).

The volume of data reported to the intermediate level will normally be less than the data generated at the service delivery level because not all data that are generated need to be reported. Data may also be aggregated for reporting, or may be reported in the form of individual records for each patient or client.

In the final level, or the national level, data from intermediate levels, or at times directly from the service delivery level, may be reported to national data collection agencies. Alternatively, data from census or surveys may be collected at this level, using data captured from the service providers, patients/clients or the general population (Mercer 2003). Data from intermediate levels, or at times directly from the service delivery level, may be reported to national data-collection agencies, the third level of use and sharing. Alternatively, data from census or surveys may be collected at this level, using data captured from the service providers, patients/clients or the general population. From this it is easy to realise that a breakdown of data collection in any stage has far-reaching ramifications for health.

Data input processes must be rapid and intuitive, without placing any additional burden on the user, or mistakes will follow. While it is unlikely that any method of data collection, other than voice, will be faster than handwritten notes, the benefits of an electronic clinical information system far outweigh any minimal change in work process that might be required.

The most obvious benefits are those of legibility, error reduction, reduced documentation of redundant data, completeness and cleanness of the data collected, and the ability to use the data for secondary purposes. By eliminating the duplication of services, improving communication and streamlining data collection, clinical information systems can improve care and the outcomes of care, reduce costs and help to offset the effects of a growing worker shortage that is especially hard-felt in nursing.

Nursing data, information, knowledge and evidence

It is acknowledged that whereas a medical practitioner may be seen as the major primary care provider, in longitudinal care, nurses embrace the concept of continuity of care as both an aim and a philosophy that affects the delivery of care (Conrick et al 2004). Continuity always involves transitions on the part of individuals, such as wellness to illness, home to hospital, and the gaps they may encounter along the way. In nursing, these transitions usually involve practice that deals with populations who have complex health issues. During times of transition, the nurse is very often the health professional most involved in evaluation, planning and delivering the changes in care that may be required (Conrick et al 2004). If patient care is not consistently and accurately recorded, the possible adverse effects on patient care, nursing practice and the development of nursing knowledge may be quite significant (Currell et al 2002).

A key strategy to assist with continuity of care and efficient access to health information is the standardisation of terminology used by nurses, in relation to assessment and clinical management of patients. In Australia, an initiative called the HealthOnline strategy, emphasised that nurses must decide how the ‘natural language’ text and oral data that are used in nursing can be entered into a computerised documentation system and translated, through the design of the computer software, into a database capable of supporting nationally agreed, consistent terms (Walker et al 2003). Without some type of organisation or classification, differences in language can be quite marked from hospital to hospital, and this is, of course, increased between states and territories, resulting in inappropriate interpretation of the record and the key process of nursing care being measured in different ways (Conrick 2005).

The development of a health information infrastructure in electronic format must (ultimately) be capable of supporting machine-readable terminology, as this will ensure that data can be readily accessed electronically. Nursing must be active in determining how health concepts are defined by computer software to ensure standardisation and accurate communication, meaning that a computer used by a nurse in one area is using the same concept (with the same meaning) when interacting with a computer used by a health practitioner elsewhere.

The development of classifications and terminologies is a priority, because they enable the standardised collection of machine-readable health information to:

• provide for the measurement of clinical care outcomes and support an evidence-based approach to client assessment—evaluating care outcomes for individuals requires the capacity to organise patient-based information from a variety of service delivery settings in both public and private sectors

• flow into case management and decision support software

• facilitate coordinated care across sectors (acute care, emergency, other ambulatory and community health settings, non-acute settings)

• improve the monitoring of safety and quality in healthcare

• enable statistical analysis and reporting of health information for decision making, policy development, service administration and financial management, and health research, and

• enable standardised indicator development (Walker et al 2003).

Defining the language of practice is also necessary so that all care settings are using the same unique terms. These factors are critical if service providers are to continuously improve safety, enhance the quality of health and healthcare, and to base their practice on evidenced-based research (Walker et al 2003). If language collection and definition can be achieved, it will enable activities such as outcomes research and benchmarking based on valid, consistent and reliable data. It will also underpin the development of nursing archetypes (discussed later in this chapter).

The patient’s health record, whether electronic or paper, should contain a complete record of nursing work. In fact, this is the only place that it can be captured, but frequently the care given and outcomes of nursing care are poorly reported. The lack of structure of nursing data also means that they are infrequently used to support nursing practice because retrieval from patients’ records is very difficult (Conrick 2005). These problems have existed for a long time, but it is still sobering to read recent studies that indicate that fragmented, disorganised and inaccessible clinical information continues to adversely affect the quality of healthcare and compromises patient safety (Gahart et al 2004). To provide better care for patients, it is essential that all clinicians and others involved in a patient’s care can accurately communicate treatment plans, assessments, patient diagnoses and symptoms.

Information technology enables the sharing and storage of data not possible with paper-based records and other current means of communication. However, it must be done in an appropriate, specific and accurate manner, and the only way to achieve this is the use of standard, accepted, relevant terminology or terminologies that both the senders and receivers of information can understand. In an electronic environment, standard reference terminologies are required, and nursing has developed an International Reference Terminology (IRT) for this purpose. Such terminologies communicate information well, but at a higher level, and they are not suited for counting information units for statistical purposes. In order to both communicate health information, and to count it accurately (for burden of disease studies, epidemiology, public health initiatives, resource planning and so forth), both classifications and terminologies are needed (Walker et al 2003).

While humans communicate with each other using ‘natural language’, computers cannot; they need to be told what things are and how they are related to each other, and this is achieved through use of terminologies. Despite the considerable terminologies work that is underway in Australia and internationally, little has been done to identify those that will be acceptable to Australian nurses. Nurses, as they should, have rejected language classification systems that were inadequate or inappropriate, but with the implementation of electronic health records, consensus on language classification must be achieved. One of the most difficult problems has been finding an appropriate terminology that represents the spectrum of nursing practice, while making sense to both the user and the computer. There are several datasets that appear to have some merit and that are in use elsewhere, and they must be trialled in Australia.

Workforce challenges

Other than the state of its data, there are a number of factors that have the potential to undermine the use of technology to support nursing. Nursing workflow issues are some of the most important of these and they must be understood if nurses’ information requirements are to be realised. Consideration of these issues is also necessary for nurses to work seamlessly across the continuity-of-care with individual patients or groups of patients or in interdisciplinary care teams. Although substantial investment may be expended on technology, this will not necessarily guarantee success, as nurses will not willingly use tools incompatible with their work or communication processes. Imposing information systems is also futile, as this usually results in the collection of sporadic, poor-quality data, which may impact on clinical decisions made by nurses.

Investment in information technology infrastructure also requires an investment in the health workforce to ensure that nurses have the skills required to effectively use the information and technology, and to enter the technology debate. Few universities offer sufficient informatics education to their undergraduate or postgraduate students, and nurses not recently qualified are likely to have minimal ‘training’ at work or may have undertaken self-education because of a particular interest in the field. A comprehensive national health informatics education framework is required to address this crucial issue.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access