- Anatomical features of the urinary tract

- Distinction of upper and lower urinary tract infection (UTI)

- Factors that predispose to UTI

- Bacterial species causing UTI

- Collection of urine for microbiological testing

- Microbiological examination of urine

- Application of rapid dipstick testing of urine in diagnosis of UTI

In this chapter and Chapter 22, attention is focused on the work of the clinical microbiology laboratory. Of all microbiological tests conducted in clinical laboratories, urine microscopy, culture and sensitivity is the most frequently requested. The test is used to help make or exclude a diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) among patients who exhibit signs and symptoms of UTI, and among patients who are asymptomatic, but at high risk of UTI. After the respiratory tract, the urinary tract is the most frequent site of bacterial infection.

Normal physiology

The urinary tract

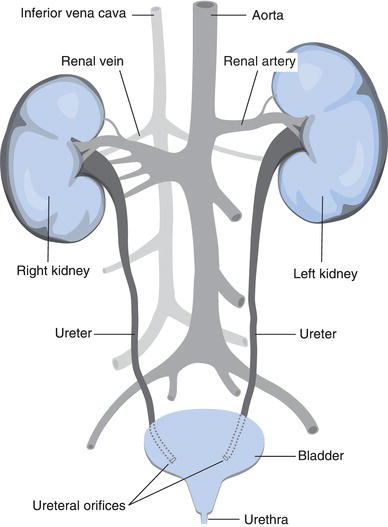

The urinary system (Figure 21.1) comprises the kidneys and ureters (the upper urinary tract), and bladder and urethra (lower urinary tract). The nephrons in kidneys are the site of urine formation, a topic considered in Chapter 5. Urine flows from nephrons into a system of collecting ducts. These ducts join at the pelvis of the kidney, where urine leaves the kidney.

Urine is continuously conducted from the pelvis of each kidney to the bladder, via two tubes called ureters. The walls of the ureters contain smooth muscle. Peristaltic contractions of this muscle wall, occurring around three times per minute, propel urine towards the bladder. The ureters are joined obliquely to the bladder at its base, and urine enters the bladder in continuous spurts due to the peristaltic action of the ureters. The oblique entry of ureters to bladder ensures that the opening to the bladder is kept closed, except during peristaltic contraction when urine enters. This effectively prevents urine passing from the bladder in the reverse direction up the ureters.

The bladder is an innervated muscular bag whose function is to store urine prior to urination, and expel all the urine it contains at the time of urination. The volume of the bladder increases as it fills with urine. Between 150 ml and 400 ml of urine are collected in the adult bladder before the conscious need to urinate arises; as accumulated volume increases beyond 400 ml this need becomes increasingly urgent and painful. A sphincter muscle (the external urethral sphincter), situated where the urethra joins the bladder, prevents accumulating urine leaving the bladder. At the time of urination this sphincter is relaxed; the detrusor muscle in the wall of the bladder contracts, forcing urine out of the bladder and urine flows from the bladder down the urethra.

The urethra is the tubular structure through which urine flows on the final part of its journey from the bladder out of the body. In females the opening of the urethra (called the meatus) is above and in front of the vaginal opening, and in the male it is at the tip of the penis. The male urethra is thus significantly longer than the female urethra.

Bacteria in the urinary tract

The urinary tract, from kidney to the final distal third of the urethra, normally contains no bacteria, so that in health the urine present in the bladder is sterile. Bacteria normally present on the skin of the perineum and in faeces can find their way up the urethra, so that bacteria may be present without any untoward effect in the lower third of the urethra. The normal flushing effect of urine as it passes down the urethra and other non-immune and immune defence against bacterial invasion serve to keep this bacterial contamination of urethra under control. In health, normally voided urine is either sterile (contains no bacteria) or contains low numbers of bacteria, flushed from the urethra during urination.

Urinary tract infection

Route of infection

Urinary tract infection (Figure 21.2) most often results from ascending infection by bacteria that constitute part of the normal bacterial flora of either the gastrointestinal tract or skin. Bacteria normally present in the gastrointestinal tract are present in faeces. These bacteria find their way from the perianal region via the perineum to the urethra and up into the bladder. The skin of the perineum is also a source of urinary tract pathogens. Bacteria that are normally present specifically in the female genital tract are a less common cause of UTI.

Infection and resulting inflammation of the bladder is called cystitis. This is the most common form of UTI. In a minority of individuals infection spreads up the urinary tract, infecting the kidney. Although far less common than infection of the lower urinary tract, infection of the kidney (pyelonephritis) is more serious than cystitis. Scarring of kidney tissue can in the long term reduce kidney function. Chronic infection of the kidney may result in renal failure. Pyelonephritis is associated with increased risk of infection spreading to the blood causing septicaemia and sepsis.

Although the ascending route of infection is the most usual, UTI may be caused by septicaemia. In this case bacteria present in blood may initiate descending infection of the urinary tract affecting first the kidneys and then the lower urinary tract.

Predisposing factors

Gender

The relatively short female urethra is considered the principle reasons for the particular susceptibility of women to ascending UTI. Around a third of all women have a UTI before the age of 261, whilst for men under the age of 50 UTI is rare. The incidence of UTI infection among men increases significantly with age past 50 years, so that there is no gender difference in UTI prevalence among elderly patients. Among children, girls are more prone to UTI than boys.

Sexual activity

Women who are sexually active are more likely to suffer UTI than those who are not.

Pregnancy

Changes in the urinary tract from early in pregnancy increase the risk of bacteria present in the bladder spreading up the urinary tract with resulting pyelonephritis. For this reason all pregnant women are screened for the presence of significant numbers of bacteria in urine (bacteriuria) at least once during the first half of pregnancy.

Urine stasis

One of the principle physiological processes that prevents UTI is the flushing effect of sterile bladder urine through the lower urinary tract. Any disease process that inhibits urine flow or complete bladder emptying increases the risk of UTI. Obstruction of the urinary tract by stones (urinary calculi) or tumour, and disease of the prostate, which all impair urine flow, contribute to the increased incidence of UTI in older men, compared with younger men. Constipation is associated with incomplete bladder emptying and resulting predisposition to UTI, particularly among those with chronic constipation.

Immunosuppression

A suppressed immune system reduces host defence against bacterial invasion of the urinary tract. This explains the increased incidence of UTI among HIV patients and those who have been given immunosupressive drug (e.g. transplant patients). Generalised reduced immunity is a feature of advancing years and contributes to pathogenesis of UTI in the elderly.

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetics are more likely to suffer infections than non-diabetics. Urinary tract infection is a particular complication of long-standing diabetes.

Vesicoureteral reflux

Anatomy of the normal urinary tract prevents urine from passing from the bladder back into the ureters. Vesicoureteric reflux is a pathological condition in which reflux of urine from bladder to ureters greatly predisposes to ascending infection with resulting pyelonephritis. This is a particular problem among children and is a major cause of pyelonephritis among this age group. Other congenital abnormalities of the urinary tract cause UTI in babies and young children. If not identified and treated these anomalies, and associated recurrent UTI can lead to renal failure later in life. For this reason, UTI in childhood often warrants intensive urological investigation2.

Hospitalisation

Illness that necessitates a stay in hospital is quite commonly associated with a temporary state of reduced immune defence against infectious disease. Furthermore the hospital environment is one in which the risk of coming into contact with infectious organisms is high. It is perhaps not surprising then that many patients acquire an infection as a direct result of being admitted to hospital. Around half of all patients in hospital who are suffering an infection, acquired the infection after admission. The principle site of hospital acquired (nosocomial) infection is the urinary tract; around 40% of all nosocomial infections are UTIs3. Patients at particularly high risk of nosocomial UTI are those who require urine catheterisation or cystoscopy (endoscopic examination of the urinary tract). Urological surgery is also associated with an increased risk of UTI. All patients who require long-term catheterisation, that is for more than a month, whether in hospital or the community, almost inevitably contract a UTI, though most are asymptomatic (i.e. they have significant bacteriuria, but do not feel unwell).

Signs and symptoms

Lower UTI (cystitis)

The principle signs and symptoms of cystitis are:

- Frequent urge to urinate even when there is not much urine in the bladder (frequency and urgency).

- Burning pain during and immediately after urination (dysuria).

- Supra-pubic pain (i.e. pain in the lower central abdomen).

- Fever may be a feature.

Upper UTI (acute pyelonephritis)

Those with upper UTIs are usually significantly more unwell than those with uncomplicated cystitis. Principle signs and symptoms include:

- Fever and rigors (fits of shivering).

- General malaise with nausea and vomiting.

- Renal (i.e. low back/flank) pain.

- Symptoms of lower UTI may also be present.

Microbiological examination of urine

Specimen collection (MSU)

The sample required is a ‘clean catch’ mid stream specimen of urine (Table 21.1). It is important that the sample is taken before antibiotics are given, as these can reduce the numbers of any bacteria present, resulting in a falsely negative result. If antibiotics have been given, then this should be stated on the accompanying request card.

Specimen collection (CSU)

The once widely adopted practice of catheterising patients simply to obtain a specimen of bladder urine for microbiological testing was abandoned when it was realised that the process of catheterisation itself increases the risk of UTI. However the collection of a catheter specimen of urine (CSU) is necessary for the investigation of catheterised patients. Any bacteria present in bladder urine will quickly multiply as it stands in a catheter drainage bag. Urine should not therefore be sampled from the drainage bag; it will give a false impression of the bacterial content of bladder urine. Urine should instead be sampled using scrupulous aseptic technique by syringe and needle from the self-sealing sleeve of the drainage tube. Aseptic technique is important for three reasons:

| OBJECTIVE To collect a specimen of bladder urine uncontaminated by bacteria which may be present on:

Any bacteria present in the urethra are washed away in the first portion of urine voided. This is not collected. All other potential contamination is avoided by thorough cleansing and effective asceptic technique. PROTOCOL (for women) 1. Wash hands thoroughly with soap and water and dry.

2. With one hand separate the labia. 3. Area around the urinary meatus must be cleansed from front to back with soap and water and dried. 4. Still with labia separated, the patient voids the first 20 ml or so of urine into the toilet bowl, and then collects a portion of the remaining urine passed into a sterile universal container. 5. Screw on cap of urine bottle immediately taking care not to touch either the rim of the bottle of inside of the bottle cap. Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|