There are four parts to this section:

1 Commencing an intravenous infusion

2 Priming the equipment for intravenous infusion

3 Maintaining the infusion for a period of time

4 Care of a Hickman catheter for long-term intravenous therapy

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section, you should know how to:

▪ prepare and support the patient for these nursing practices, both at home and in an institutional setting

▪ collect and prepare the equipment

▪ assist the medical practitioner with the safe insertion of an intravenous cannula or catheter

▪ maintain an intravenous infusion as prescribed.

Background knowledge required

Revision of the anatomy and physiology of the cardiovascular system, with special reference to the circulation of the blood, and body fluids

Revision of ‘Aseptic technique’ (seep. 386)

Review of local policy in relation to intravenous therapy in both community and institutional care.

Indications and rationale for intravenous infusion

An intravenous infusion is the introduction of prescribed sterile fluid into the blood circulation; it may be indicated for the following reasons:

▪ to maintain a normal fluid, nutrient and electrolyte balance when the patient is unable to maintain adequate intake by mouth and nasogastric feeding is inappropriate, e.g.:

—a patient during the preoperative and postoperative periods

—a patient who has had surgery involving the alimentary system

—a patient who has malabsorption problems

▪ to replace severe fluid loss in emergency situations, e.g.:

—a patient who has severe haemorrhage and haemorrhagic shock

—a patient who has severe burns or scalds

—a patient dehydrated by vomiting or diarrhoea usually associated with enteric infection

▪ to administer medication when other routes are not appropriate or when there is a need for a rapid-onset action or accurate titration of the dose, e.g.:

—analgesic medication for effective pain relief

—chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with malignancy.

Outline of the procedure

Intravenous therapy is prescribed by the medical practitioner and initiated by a doctor or a nurse who has undertaken specialist training and is deemed competent to carry out this procedure. The non-specialist nurse may be required to help with the procedure, to maintain the infusion safely for a period of time and to undertake removal of the cannula.

Using an aseptic technique, the competent practitioner chooses a suitable vein site for access, body hair should be clipped as necessary and the site cleansed with antiseptic lotion such as a chlorhexidine and alcohol-based solution, which is allowed to dry fully before the skin is punctured (Pellowe et al 2004). Shaving body hair is no longer recommended as it has been suggested that it can increase bacterial colonisation of the skin (Royal College of Nursing 2003). A topical preparation of local anaesthetic, i.e. Emla cream, can be applied to the skin surface approximately 2 hours prior to the procedure, or Ametop, which can be applied 10 minutes before the procedure (Scales 2005).

A sterile cannula is inserted into the vein so that the prescribed infusion fluid can enter the patient’s blood circulation. The infusion fluid flows into the cannula through an administration set that will have been primed ready for use. The cannula is secured in position and covered by a sterile dressing. The flow of infusion fluid is maintained, and the containers of fluid replaced as prescribed, until the intravenous infusion is discontinued (Royal College of Nursing 2003).

Short-term intravenous therapy

The metacarpal veins and the dorsal venous arch at the back of the hand or the superficial veins of the wrist or lower arm such as the cephalic or basilica veins (Scales 2005) are chosen for short-term infusions expected to last for a few hours or days. Cannulation increases the risk of venous thrombosis in the veins used for access; if this occurs in the smaller branches of the peripheral veins following an infusion, it is still possible to use the larger branches of the same vein at a later date if required. The veins of the lower limbs are rarely used because of the increased risk of thrombosis as a result of a slower venous flow. The non-dominant limb should be used if possible to minimise the patient’s discomfort and promote independence.

Long-term intravenous therapy

1. Trolley or tray

2. Sterile dressings pack, if required

3. Sterile cannula sizes 18–22 gauge depending on fluids to be infused

4. An antiseptic solution such as chlorhexidine in alcohol for cleansing the skin (as per local policy)

5. Non-sterile gloves/apron

6. Sterile administration set

7. Prescribed sterile infusion fluid

8. Sterile semipermeable cannula dressing

9. Infusion stand

10. Tourniquet

11. Hypoallergenic tape

12. Receptacle for soiled disposable items.

Additional equipment if required

Scissors for clipping any body hair

Infusion fluids

The most commonly prescribed fluids are:

normal saline (sodium chloride 0.9%)

dextrose 5% in water

Ringer’s lactate/Hartmann’s solution

plasma or plasma expanders, e.g. Haemaccel or Gelofusine

blood (see ‘Blood transfusion’, p. 47)

parenteral nutrients (see ‘Parenteral nutrition’, p. 240).

Most prescribed fluids are commercially prepared in sterile containers, being labelled ‘FOR INTRAVENOUS INFUSION’. They may also be prepared by the hospital pharmacy. The containers used for these preparations are frequently soft plastic bags protected by an outer covering (see the manufacturer’s instructions), although glass bottles or semi-rigid plastic containers (Polyfusors) are still used for some preparations.

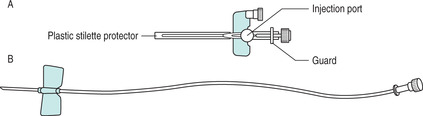

Cannulae

Various cannulae (Fig. 21.1) are available and are prepared commercially in sterile packs. Size 18–14 gauge can be used for the administration of fluids very quickly such as in a resuscitation event. However, smaller gauge cannulae are preferred, as they cause less damage to the inner vessel wall. A gauge 22 would be sufficient size to deliver maintenance therapy as it can deliver up to 42 ml min—1 or 2.5L h—1, (Scales 2005). Those chosen by the competent practitioner have an inner needle surrounded by a plastic cannula. The needle is withdrawn once the vein has been punctured, allowing blood to flow back. Once the cannula is safely in situ, the infusion fluid is connected and the cannula secured in position. Some cannula packs include an accompanying syringe, e.g. Medicut. Small winged needles are used for access to scalp veins in babies and young children, and for elderly patients who have fragile veins.

|

| FIGURE 21.1Intravenous infusion: cannulae in common use A Cannula used when intravenous drugs are to be administered with the infusion or post-infusion B Cannula used preoperatively for short-term infusion |

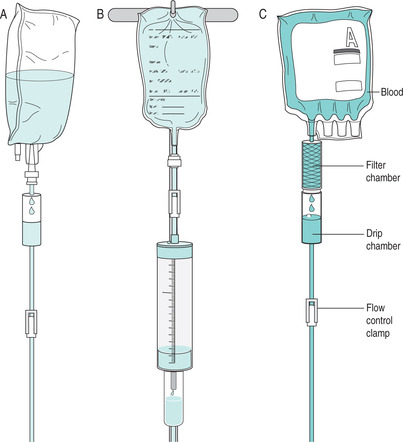

Administration sets

Administration sets are commercially prepared in sterile packs. The set contains specialised sterile tubing with, at one end, a rigid trocar protected by a sterile sheath. At the other end is a similarly protected Luer connector nozzle. Towards the trocar end, the tubing widens into a drip chamber. An adjustable roller clamp surrounds the tubing below the drip chamber, which allows the flow of fluid to be regulated at the prescribed flow rate. Blood administration sets include a filter and should be changed at the end of transfusion or at 24 hours (Royal College of Nursing 2003). Simple administration sets are available without a filter, for the infusion of crystalloid fluids (Fig. 21.2). These should be changed every 72 hours (Royal College of Nursing 2003).

|

| FIGURE 21.2A Standard administration set B Blood administration set C BuretteFrom Nicol et al 2003, with permission |

Specialised administration sets (burette sets)

A specialised administration set is used for infusions when a volumetric infusion pump is not available and a more accurate control of flow rate is needed. The burette can also be used to mix and administer drug infusions, which should be infused over short periods of time. They are also particularly important in reducing the risk of fluid overload when infusions are prescribed for babies or young children. The burette set has a calibrated drip chamber with one roller clamp above and one roller clamp below. The drip chamber is filled with the amount of fluid prescribed in millilitres per hour, and this amount of fluid is infused during 1 hour. The flow rate will depend on the drop factor and the amount prescribed (see the manufacturer’s instructions). For the infusion to continue, the drip chamber has to be refilled as prescribed each time it has emptied.

Volumetric infusion pumps

Some volumetric infusion pumps are used with specific sterile cassettes (e.g. Accuset) as well as a normal administration set so that an accurate flow of fluid can be maintained during the infusion. When primed and connected, these can be set to infuse fluid within a range of 1–999 ml h—1. Other volumetric infusion sets simply use a specifically adapted administration set. The infusion is controlled by a column of electronically controlled rollers that adjust the flow rate as required, constantly monitoring the rate, total volume infused and infusion pressure. This equipment must be mechanically serviced as per the manufacturer’s guidelines and local policy.

Syringe pumps

Syringe pumps are used to deliver drug infusions over a prescribed period of time. Patient controlled analgesia (PCA) is delivered via a syringe pump (Fig. 21.3).

▪ help to explain the nursing practice to the patient to gain consent and co-operation and encourage participation in care

▪ ensure the patient’s privacy, respecting his or her individuality

▪ help to collect and prepare the equipment. Wash hands using appropriate procedure (Jeanes 2005) and wear non-sterile gloves to prevent contamination with body fluids (Royal College of Nursing 2003)

▪ check the prescribed infusion fluid with a registered nurse or medical practitioner. This is a legal requirement and part of professional practice

▪ prime the administration set with the infusion fluid, maintaining asepsis, so that it is ready once the cannula is in position

▪ place the infusion fluid on the stand beside the patient, check that it is running freely and that all air has been expelled from the system. This prevents any danger of air embolus. If not connected immediately, the end should be protected by replacing the sterile cap to prevent contamination

▪ help the patient into as comfortable a position as possible so that he or she will tolerate the intravenous therapy without distress

▪ expose and support the area for cannulation to facilitate access

▪ help to prepare the sterile equipment as required, to maintain a safe environment

▪ apply pressure around the limb above the cannulation site as directed using a tourniquet. This will retain more blood in the veins and facilitate cannulation

▪ release the pressure as directed once the venous cannula is correctly positioned and the infusion lines are connected, to commence the flow of fluid to the veins

▪ regulate the flow rate as prescribed to maintain the prescribed fluid intake

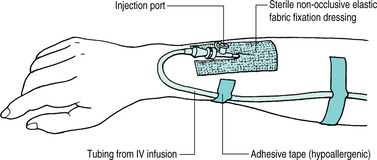

▪ help the competent practitioner to secure the dressing and tubing to maintain asepsis and prevent disconnection of the tubing and cannula (Fig. 21.4)

|

| FIGURE 21.4Anchoring the tubing with adhesive tape |

▪ apply a splint to the limb if the site of the infusion requires the limb to be immobilised. This is not routine practice

▪ ensure that the patient is left feeling as comfortable as possible so that he or she will continue to tolerate the intravenous therapy. Comfort helps to reduce stress levels and promotes healing

▪ dispose of equipment safely to prevent the transmission of infection

▪ document this nursing practice appropriately, monitor the after-effects and report any abnormal findings immediately, ensuring safe practice and enabling prompt, appropriate medical and nursing intervention to be initiated as soon as possible

▪ maintain the infusion at the prescribed flow rate for continuation of the treatment. To reduce the risk of infection, administration sets should be changed as per local policy and immediately following the infusion of blood products (Royal College of Nursing 2003). On-going care involves regular monitoring of the site to identify localised infection, infiltration of fluid into the surrounding tissue or the development of thrombophlebitis. Royal College of Nursing (2003) and Scales (2005) advocate the formal monitoring of cannulation sites daily using a graded 5-point assessment tool (Fig. 21.5)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access