CHAPTER 21. Becoming a critical thinker

Steve Parker

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

• describe the essential nature of critical thinking

• describe the main characteristics of a critical thinker

• explain the basic structure of an argument

• apply the basic structure of an argument to various areas of nursing practice, and

• identify resources for further reading and the study of critical thinking.

KEY WORDS

WHAT IS CRITICAL THINKING?

There are a variety of definitions of critical thinking and no consensus on any one of them (Riddell 2007). This situation means we need to be careful about relying on any one definition. In essence, however, critical thinking refers to the activity of questioning what is usually taken for granted.

Whether we are aware of it or not, all behaviour is based on certain values, assumptions and beliefs. These form the basis for our decisions to act in certain ways. In a professional context such as nursing practice, everything that we think, say or do is the result of a complex web of beliefs, values and assumptions that have formed as a result of our life experiences. As we grow up in our family, attend school, participate in religious communities, associate with friends, watch television, read newspapers, and work for various employers, we develop a ‘pair of spectacles’ through which we understand and interpret the world and all that happens in it. Just as a person who wears glasses eventually becomes unaware that they are even wearing them, so too each of us adjusts to our worldview ‘spectacles’ until, often, we are completely unaware what values, beliefs and assumptions are influencing us in a specific situation.

Critical thinking means stopping and reflecting on the reasons for doing things the way they are done or for experiencing things the way they are—focusing on what is frequently taken for granted and evaluating the values, beliefs and assumptions that are held, and asking whether or not what is done and thought is justifiable or not. These characteristics of critical thinking imply a self-consciousness of what, how and why we are thinking, with the intention of improving thinking. In short, ‘critical thinking is thinking about your thinking while you’re thinking in order to make your thinking better’ (Paul 2008). Improving thinking is essential because it is intimately related to the many decisions that need to be made each day. The quality of our lives is determined by the quality of our decisions, and the quality of our decisions is determined by the quality of our reasoning (Schick & Vaughn 1995). In particular, ‘[i]f nurses are to deal effectively with complex change, increased demands and greater accountability, they must become skilled in higher level thinking and reasoning abilities’ (Simpson & Courtney 2002:89).

An important aspect of critical thinking is healthy scepticism. This scepticism is necessary because there are many attempts to persuade people to accept various claims. These attempts to persuade also occur in professional contexts. For example, research reports suggest changes to practice; peers argue that their way of acting is the right one; therapists promote various interventions; administrators argue that certain changes need to be made to the workplace; and so on. Often these claims are contradictory, so they cannot all be acceptable.

Practitioners need to sort through all these, often competing, claims. To accept them all without question will, at best, be highly confusing and, at worst, may endanger the lives of others if actions are based on wrong information or conclusions. To adopt an attitude of healthy scepticism means to cautiously listen to or read the claims that others make, carefully evaluating their legitimacy, and not rushing to accept a conclusion without careful thought.

The same rigorous thinking needs to be done about our own nursing practice. We make decisions every moment, which we assume are of benefit to our patients. Asking questions about the practices we engage in, including what evidence is available to support their efficacy, is essential if our nursing practice is to produce positive outcomes for those for whom we care.

It is possible, of course, to become too pedantic, resulting in inaction because we are not prepared to accept anything unless it is 100% proven. This is why the scepticism needs to be healthy. There is a limit to what can be known for certain. And part of critical thinking is knowing these limits and making the best evaluation under the circumstances.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CRITICAL AND CREATIVE THINKING

Critical thinking is not the same as creative thinking. According to Miller and Babcock (1996:117), creative thinking is, among other things, more divergent, messy, unpredictable, provocative, spontaneous and playful than critical thinking. They describe critical thinking as selective, orderly, predictable, analytical, judgmental and evaluative.

Creative thinking, although different from critical thinking, is an essential, complementary process to critical thinking. As a practitioner, there are many situations that arise that do not fit with the ideal or that are not predictable. No individual person for whom nurses care ever fits the ‘average’ because each person and situation is unique. In order to solve problems for these unique situations and individuals, the practitioner needs to be able to develop new approaches and solutions so that all parties have their needs met. Miller and Babcock suggest that:

Creative thinking is very useful when what we know and what we know how to do are not working, including the rules of reason, common sense, gravity, and routine. The creative thinker is willing to think wildly, without having any idea where her or his path of thinking may lead. Deliberative cognition is temporarily held in abeyance (Miller & Babcock 1996:120).

Because creative thinking is so ‘chaotic’ it means that it needs to be evaluated to ensure that any conclusions that are reached are appropriate. In this regard, Ruggiero understands the mind to have two phases:

It both produces ideas and judges them. These phases are intertwined; that is, we move back and forth between them many times in the course of dealing with a problem, sometimes several times in the span of a few seconds (Ruggiero 1998:81).

In the past, critical thinking has often been presented apart from creative thinking. However, in practice, creative and critical thinking go hand-in-hand. Without creative thinking, critical thinking would be dry and mechanical. Without critical thinking, creative thinking would be chaotic and inefficient. As Ruggiero (1998:81) asserts, ‘[t]o study the art of thinking in its most dynamic form [where creative and critical thinking are intertwined] would be difficult at best’. Consequently, in practice, we need to consider them separately. However, although critical thinking and creative thinking are distinct from each other, they should never be separated.

THE CHARACTERISTICS OF CRITICAL THINKING

So what are the characteristics that a critical thinker will demonstrate?Jacobs et al (1997) have developed a set of observable skills that indicate the presence of critical thinking. These are grouped into categories, as described below.

First, a critical thinker needs the ability to integrate information from all relevant sources by being able to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant data, validate data that are obtained, recognise when data are missing, predict multiple outcomes, and recognise the consequences of actions.

Second, to think critically means to be able to examine assumptions by recognising them when they are present, detect bias, identify assumptions that are not stated, recognise the relationships of action or inaction, and transfer thoughts and concepts to diverse contexts, or develop alternative courses of action.

Third, it is important for the critical thinker to be able to identify relationships and patterns. This includes recognising inconsistencies or fallacies of logic, working out generalisations, developing a plan of action consistent with a model, and, where appropriate, seeking out alternative models.

Jacobs et al offer a definition of critical thinking that incorporates all these characteristics:

Critical thinking is the repeated examination of problems, questions, issues, and situations by comparing, simplifying, synthesizing information in an analytical, deliberative, evaluative, decisive way (Jacobs et al 1997:20).

Many more examples of various ways of describing the characteristics of critical thinking could be offered. One way of summarising these is to focus on critical thinking as reasoning. The heart of reasoning is the argument. In what follows, the nature of argument will be described, followed by a survey of the ways in which arguments ‘appear’ in nursing. Suggestions will then be offered regarding the way in which the principles of critical thinking might be applied in these areas. By doing so, the way in which this approach synthesises the skills of critical thinking will become obvious.

WHAT IS AN ARGUMENT?

In colloquial language the word ‘argument’ is often used for a shouting match between two people who are having a disagreement where the participants are very angry, abusive or physically aggressive. There may be shouting, pointing of fingers, threats, crying, name-calling, and so on.

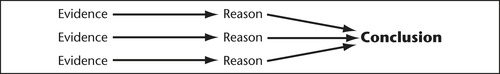

However, in critical thinking, the term ‘argument’ does not apply to these situations. In fact, these situations are the very opposite of critical thinking. In critical thinking, an argument consists of a conclusion and one or more reasons that are intended to support the conclusion. Figure 21.1 shows the relationship between these parts of an argument. Each reason may or may not have evidence that is intended to support the reason or reasons.

|

| Figure 21.1 |

Here is an example of an argument:

Every person has the right to choose how they live their lives. Therefore, a person has the right to choose to practise life-threatening behaviours if they wish.

This is an argument because it has a conclusion (‘A person has the right to choose to practise life-threatening behaviours if they wish’) and a reason intended to support that conclusion (‘Every person has the right to choose how they live their lives’). At this stage, we are not concerned whether this is a good argument or not, only with what makes something an argument. If it were desirable, a person presenting this argument could provide some evidence for the first statement by drawing attention, for example, to various statements of human rights, the constitutions of countries, or discussions about ethics. So an argument needs to have the following:

• a conclusion, and

• one or more reasons intended to support the conclusion.

WHAT MAKES A SOUND ARGUMENT?

For an argument to be sound, three criteria need to be met. First, the reasons need to be acceptable to the person evaluating the argument. Second, the reasons need to be relevant. And, third, the reasons need to provide adequate grounds for accepting the conclusion. Govier (1992) offers a useful way to remember these three criteria, which she calls the conditions of argument. If the first three letters of the word argument (ARG) are taken on their own, each letter stands for one of the conditions of argument. That is:

A Acceptability

R Relevance

G Grounds

Govier’s definitions of each of these conditions are also useful:

• Acceptability: The premises [reasons] are acceptable when it is reasonable for those to whom the argument is addressed to believe these premises. There is good reason to accept the premises—even if they are not known for certain to be true. And there is no good evidence known to those to whom the argument is addressed that would indicate either that the premises are false or that they are doubtful.

• Relevance: [Premises are relevant to the conclusion] when they give at least some evidence in favor of the conclusion’s being true. They specify factors, evidence, or reasons that do count toward establishing the conclusion. They do not merely describe distracting aspects that lead you away from the real topic with which the argument is supposed to be dealing or that do not tend to support the conclusion.

• Grounds: The premises provide sufficient or good grounds for the conclusion. In other words, considered together, the premises give sufficient reason to make it rational to accept the conclusion. This statement means more than that the premises are relevant. Not only do they count as evidence for the conclusion, they provide enough evidence, or enough reasons, taken together, to make it reasonable to accept the conclusion (Govier 1992:68–69).

The following example illustrates these criteria:

Nurses must have a practising certificate to be employed as a nurse.

Sue does not have a practising certificate.

Therefore, Sue is not permitted to be employed as a nurse.

Statements 1 and 2 are both reasons, which are intended to support the conclusion in Statement 3. If this is a sound argument, then the reasons must be relevant and acceptable, and they must provide adequate grounds for accepting the conclusion.

Statement 1 is certainly acceptable. Most countries have a requirement that nurses need to be licensed to practise. Statement 2 is hypothetical, so we will assume that it is true for the sake of the discussion. All the reasons, then, are acceptable. The two reasons are also relevant to the issue under consideration.

The next question is whether these reasons provide adequate grounds for accepting the conclusion. We can test this by asking:

Is it possible to reject the conclusion and still believe the reasons to be true? Or, in other words, even though the reasons are true, is there a legitimate way that we can escape accepting the conclusion?

In other words, could one believe that Sue could practise and still believe that the two reasons offered are true? In this case, the answer is no. If it is true that a nurse must have a practising certificate to practise, and Sue does not have one, we are ‘compelled’ to accept the conclusion that Sue cannot practise. This argument, then, is a sound one.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree