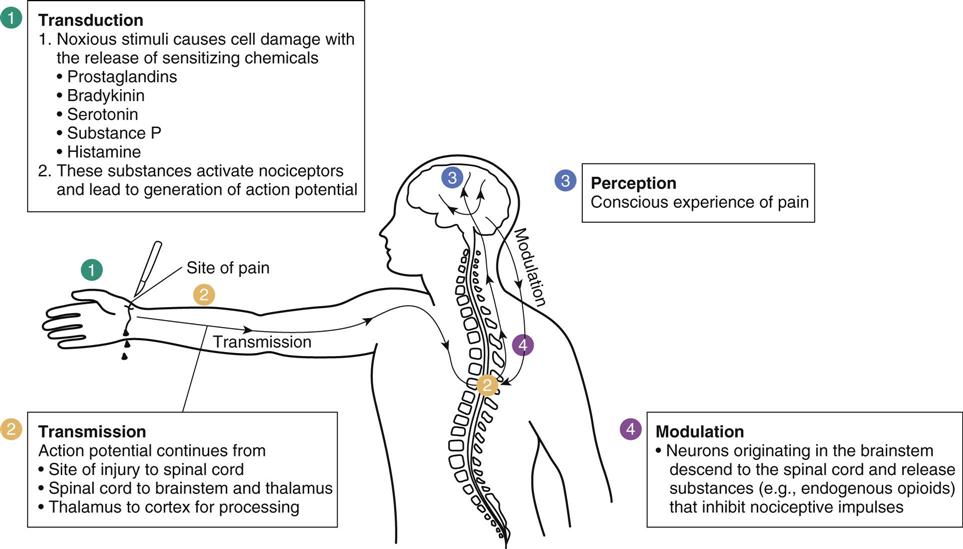

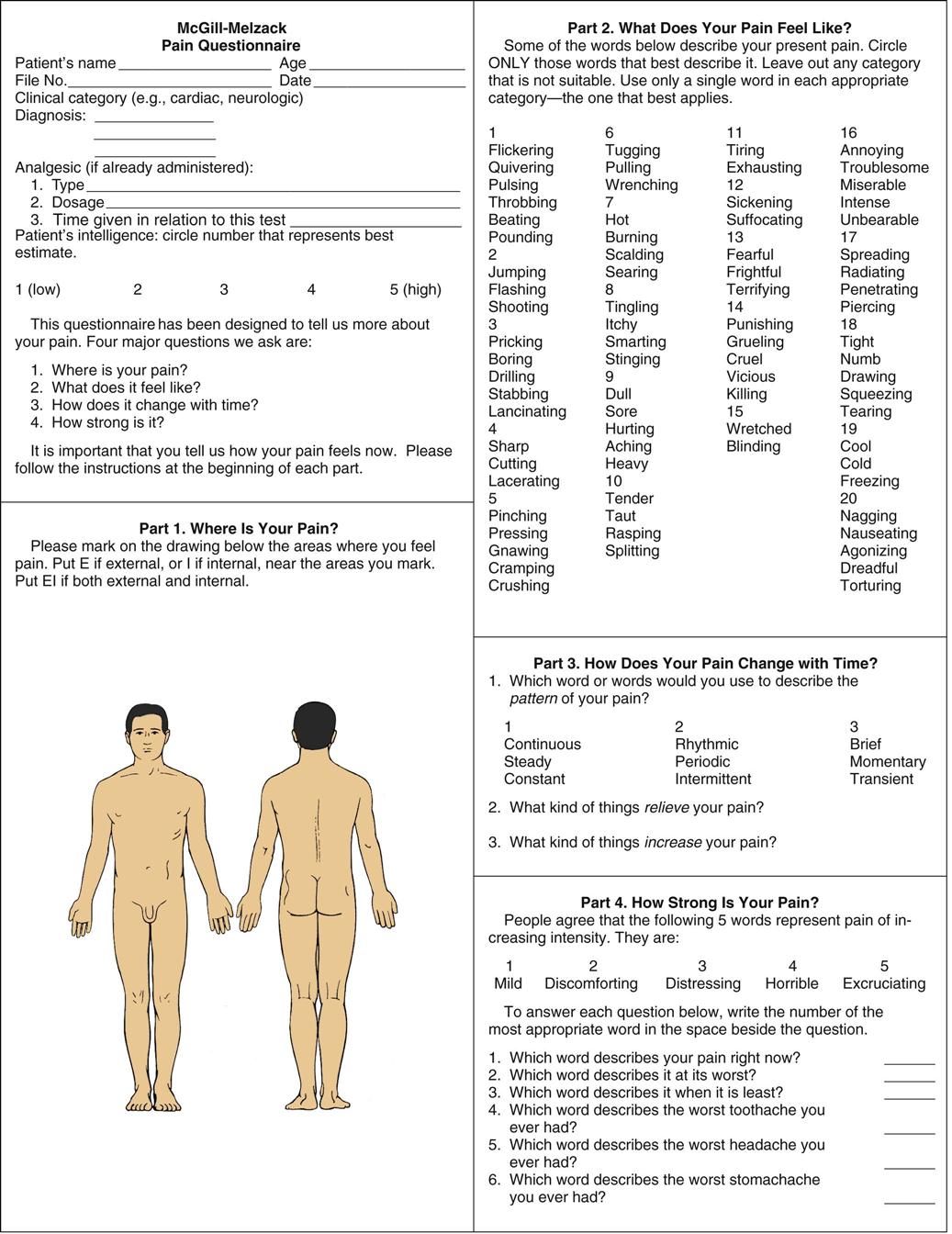

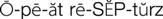

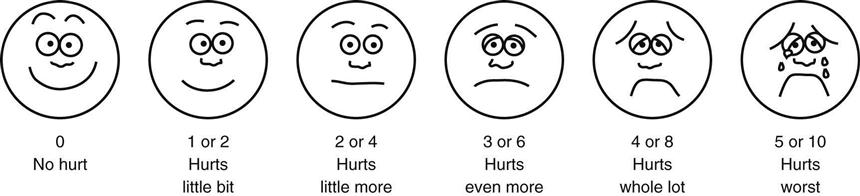

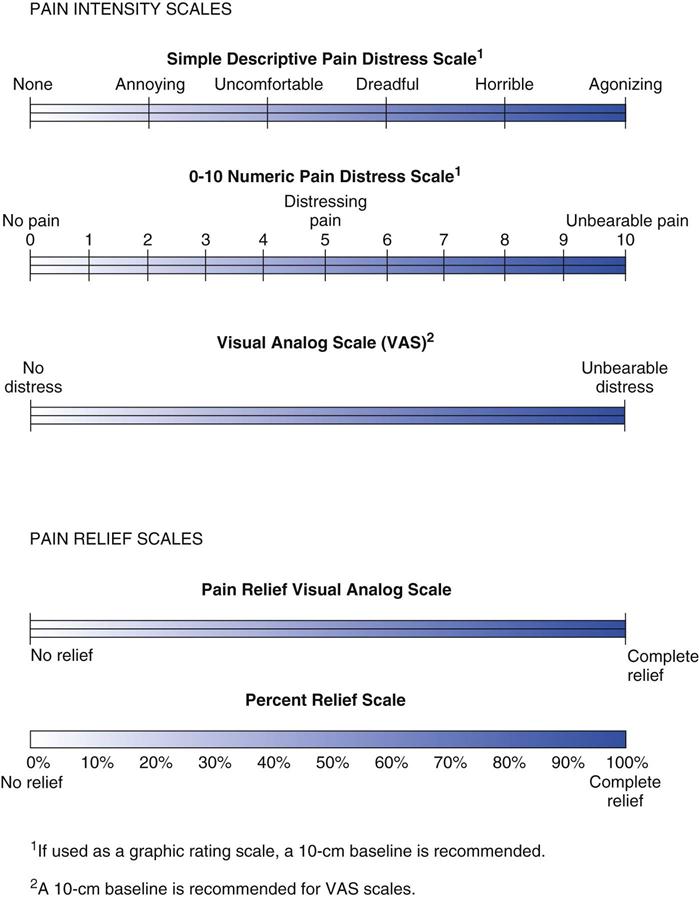

2 Describe the monitoring parameters necessary for patients receiving opiate agonists. 3 Cite the common adverse effects of opiate agonists. 5 Describe the three pharmacologic effects of salicylates. 6 List the common and serious adverse effects and drug interactions associated with salicylates. 7 Explain why synthetic nonopiate analgesics are not used for inflammatory disorders. 8 Identify the substances listed in Table 20-4 that are the active ingredients in commonly prescribed analgesic combination products. pain experience ( pain perception ( pain threshold ( pain tolerance ( nociception ( acute pain ( chronic pain ( nociceptive pain ( somatic pain ( visceral pain ( neuropathic pain ( idiopathic pain ( analgesics ( opiate agonists ( opiate partial agonists ( opiate antagonists ( prostaglandin inhibitors ( salicylates ( nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs ( nociceptors ( opiate receptors ( range orders ( addiction ( drug tolerance ( ceiling effect ( The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage.” An unpleasant sensation that is part of a larger situation is called a pain experience. The pain experience is highly subjective and influenced by behavioral, physiologic, sensory, emotional (e.g., attention, anxiety, fatigue, suggestion, prior conditioning), and cultural factors for a particular person under a certain set of circumstances. This accounts for the wide variation in individual responses to the sensation of pain. The three terms used in relationship to the pain experience are pain perception, pain threshold, and pain tolerance. Pain perception (also known as nociception) is an individual’s awareness of the feeling or sensation of pain. Pain threshold is the point at which an individual first acknowledges or interprets a sensation as being painful. Pain tolerance is the individual’s ability to endure pain. Pain has physical and emotional components. Factors that decrease an individual’s tolerance to pain include prolonged pain that is insufficiently relieved, fatigue accompanied by the inability to sleep, an increase in anxiety or fear, unresolved anger, depression, and isolation. Patients with severe, intractable pain fear that the pain cannot be relieved, and patients with cancer fear that new or increasing pain means that the cancer is spreading or recurring. Pain is usually described as acute or short term and as chronic or long term. Acute pain arises from sudden injury to the structures of the body (e.g., skin, muscles, viscera). The intensity of pain is usually proportional to the extent of tissue damage. The sympathetic nervous system is activated, resulting in an increase in the heart rate, pulse, respirations, and blood pressure. This sympathetic nervous system stimulation also causes nausea, diaphoresis, dilated pupils, and an elevated glucose level. Continuing or persistent pain results from ongoing tissue damage or from chemicals released by the surrounding cells during the initial trauma (e.g., a crushing injury). The intensity diminishes as the stimulus is removed or tissue repair and healing take place. Acute pain serves an important protective physiologic purpose that warns of potential or actual tissue damage. Chronic pain has slower onset and lasts longer than 3 months beyond the healing process. Chronic pain does not relate to an injury or provide physiologic value. Depending on the underlying cause, it is often subdivided into malignant (cancer) or nonmalignant (causes other than cancer) pain. It may arise from visceral organs, muscular and connective tissue, or neurologic factors such as diabetic neuropathy, trigeminal neuralgia, or amputation. As chronic pain progresses, especially poorly treated pain, other physical and emotional factors come into play, affecting almost every aspect of a patient’s life—physical, mental, social, financial, and spiritual—and causing additional stress, anger, chronic fatigue, and depression. Although pain has always been viewed as a symptom of a disease or a condition, chronic pain and its harmful physiologic effects are now regarded as a disease itself. Pain may also be classified by pathophysiology. Nociceptive pain is the result of a stimulus (e.g., chemical, thermal, mechanical) to pain receptors. Nociceptive pain is usually described by patients as dull and aching. It is called somatic pain if it originates from the skin, bones, joints, muscles, or connective tissue (e.g., arthritis pain) and visceral pain if it originates from the abdominal and thoracic organs. Nociception is the process whereby a person becomes aware of the presence of pain. There are four steps in nociception: (1) transduction, (2) transmission, (3) perception, and (4) modulation (Figure 20-1). Neuropathic pain results from injury to the peripheral or central nervous system (CNS; e.g., trigeminal neuralgia). Patients describe neuropathic pain as stabbing and burning. Phantom limb pain is a neuropathic pain experienced by amputees in a body part that is no longer there. Idiopathic pain is a nonspecific pain of unknown origin. Anxiety, depression, and stress are often associated with this type of pain. Common areas associated with idiopathic pain are the pelvis, neck, shoulders, abdomen, and head. Analgesics are drugs that relieve pain without producing loss of consciousness or reflex activity. The search for an ideal analgesic continues, but it is difficult to find one that meets this definition. It should be potent enough to provide maximum relief of pain; it should not cause dependence; it should cause a minimum of adverse effects (e.g., constipation, hallucinations, respiratory depression, nausea, vomiting); it should not cause tolerance; it should act promptly and over a long period with a minimum amount of sedation so that the patient is able to remain conscious and responsive; and it should be relatively inexpensive. At present, no completely satisfactory classification of analgesics is available. Historically they have been categorized based on potency (mild, moderate, strong), origin (opium, semisynthetic, synthetic, coal-tar derivative), or addictive properties (narcotic, non-narcotic). Research into the control of pain recently has given new insight into pathways of pain within the nervous system and a better understanding of precise mechanisms of action of analgesic agents. The current nomenclature for analgesics stems from these recent discoveries. In this section the medications have been divided into opiate agonists, opiate partial agonists, opiate antagonists, and prostaglandin inhibitors [acetaminophen, salicylates, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)]. The pathways of the pain transmission signal from the site of injury to the brain for processing and reflexive action have not been fully identified. The first step leading to the sensation of pain is the stimulation of receptors known as nociceptors (see Figure 20-1). These nerve endings are found in skin, blood vessels, joints, subcutaneous tissues, periosteum, viscera, and other tissues. The nociceptors are classified as thermal, chemical, and mechanical-thermal, based on the types of sensations that they transmit. The exact mechanism that causes stimulation of nociceptors is not understood; however, bradykinins, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, histamine, and serotonin sensitize these receptors. Receptor activation leads to action potentials that are transmitted along afferent nerve fibers to the spinal cord. A series of neurotransmitters (somatostatin, cholecystokinin, substance P) play roles in the transmission of nerve impulses from the site of damage to the spinal cord. Within the CNS, there may be at least four pain-transmitting pathways up the spinal cord to various areas of the brain for response. The CNS contains a series of receptors that control pain. These are known as opiate receptors because stimulation of these receptors by the opiates blocks the pain sensation. These receptors are subdivided into four types: mu (µ), delta (δ), kappa (κ), and epsilon (ε) receptors. Sigma (σ) is another receptor type that reacts to opioid agonists and partial agonists. The receptors are located in different areas of the CNS; κ receptors are found in greatest concentration in the cerebral cortex and in the substantia gelatinosa of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. They are responsible for analgesia at the levels of the spinal cord and brain. Stimulation of κ receptors also produces sedation and dysphoria. µ receptors are located in the pain-modulating centers of the CNS and induce central analgesia, euphoria, physical dependence, miosis, and respiratory depression. δ Receptors are located in the limbic area of the brain and in the spinal cord and may play a role in the euphoria produced by selected opiates. σ Receptors are thought to produce the autonomic stimulation and psychotomimetic (e.g., hallucinations) and dysphoric effects of some opiate agonists and partial agonists. The functions of the σ receptors are under investigation. Research is focusing on developing synthetic chemicals that target specific receptors to maximize analgesia but minimize the potential for adverse effects, such as addiction. As described, other chemicals—histamine, prostaglandins, serotonin, leukotrienes, substance P, and bradykinins—released during trauma also contribute to pain. Developing pharmaceuticals that block these chemicals is another effective way of stopping pain. Antihistamines (e.g., diphenhydramine), prostaglandin inhibitors (e.g., NSAIDs), substance P antagonists (e.g., capsaicin), and antidepressants that prolong norepinephrine and serotonin activity (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]) have analgesic properties. Other pharmacologic agents can suppress pain by a variety of mechanisms. Adrenergic agents such as norepinephrine and clonidine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor stimulants (e.g., baclofen, gabapentin) produce significant analgesia by blocking nociceptor activity. Valproic acid, phenytoin, gabapentin, and carbamazepine act as analgesics by suppressing spontaneous neuronal firing, as occurs in trigeminal neuralgia. Tricyclic antidepressants inhibit the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, causing the onset of analgesia to be more rapid, as well as improving the outlook of the person with chronic pain and depression. Some antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline) also block pain by antihistaminic and anticholinergic activity. Bisphosphonates (e.g., pamidronate) may be effective in treating pain associated with bony metastases. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a stepwise approach to pain management (Figure 20-2). Mild acute pain is effectively treated with analgesics such as aspirin, NSAIDs, or acetaminophen. Pain associated with inflammation responds well to NSAIDs. Unrelieved or moderate pain is generally treated with a moderate-potency opiate such as codeine or oxycodone, which are often used in combination with acetaminophen or aspirin (e.g., Empirin with Codeine No. 3, Tylenol with Codeine No. 3, Percodan). Severe acute pain is treated with opiate agonists (e.g., morphine, hydromorphone, levorphanol). Morphine sulfate is usually the drug of choice for the treatment of severe chronic pain. Other agents such as antidepressants or anticonvulsants may be used as adjunctive therapy with analgesics, depending on the causes of pain. The health care delivery system in the United States has an unfortunate, long-standing history of inadequate pain management. The Joint Commission’s current standards for pain management therapy include the following primary therapeutic outcomes: 1 Relief of pain intensity and duration of pain complaint 2 Prevention of the conversion of persistent pain to chronic pain 3 Prevention of suffering and disability associated with pain 5 Control of adverse effects associated with pain management 6 Optimization of the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) Although considered acceptable at one time, placebo therapy should never be used with pain management. One premise of pain management is that the patient should be believed when describing the presence of pain. The use of placebos implies a lack of belief in the patient’s description, and can seriously damage the patient-provider relationship. The American Pain Society has declared that the use of placebos is unethical and should be avoided. The management of all types of pain is a major health care concern. Rating pain as the fifth vital sign means that the patient’s pain should be assessed every time vital signs are taken and recorded. Vital signs charting now include a place for this record (see Figure 7-4, B); pain flow sheets have also been developed (see Figure 7-5). Taking the pain rating only when doing vital signs, however, is not sufficient. The nurse should also evaluate the pain level immediately before and after pain medications are given, at 1-, 2-, and 3-hour intervals for oral medications and at 15- to 30-minute intervals after parenteral administration. Most assessment data sheets have a section on pain management that contains the following elements: rating before and after medication, nonpharmacologic measures initiated, patient teaching performed, and breakthrough pain measures implemented. The pain flow sheet provides the health care team members with a quick visual reference to evaluate the overall effectiveness of the pain management prescribed. The American Pain Society publishes Quality Improvement Guidelines for the Treatment of Acute Pain and Cancer Pain. The American Pain Foundation has also developed the Pain Care Bill of Rights, which explains to the patient exactly what to expect and/or demand in the way of pain management (Box 20-1). Nurses must assist the patient in managing pain. The first important step in this process is to believe the patient’s description of the pain. Pain brings with it a variety of feelings, such as anxiety, anger, loneliness, frustration, and depression. Part of the patient’s response is tied to past experiences, sociocultural factors, current emotional state, and beliefs regarding pain. Psychological, physical, and environmental factors all must be considered in managing pain. Never overlook the value of general comfort measures such as a back rub, repositioning, and the use of hot or cold applications. A variety of relaxation techniques and diversional activities may prove psychologically beneficial. Decreasing environmental stimuli to ensure the patient gets successful periods of rest is essential. The patient’s pain must be evaluated in a consistent manner. A wide variety of assessment tools have been developed to enable health care providers to gain some degree of uniformity in interpreting and recording the patient’s description of pain. Some of the pain assessment tools for use with infants and young children include the following: Riley Infant Pain Assessment Tool; Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability (FLACC) Scale for use in nonverbal patients; Pain Observation Scale for Young Children (POCIS) intended for children 1 to 4 years of age; Modified Objective Pain Score (MOPS) intended for children 1 to 4 years of age after ear, nose, and throat surgery; Toddler-Preschooler Postoperative Pain Scale (TPPPS) for use in evaluating pain in smaller children during and following medical or surgical procedures; Postoperative Pain Score (POPS) for infants having surgical procedures; and Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPS) for pain in preterm and full-term neonates used to monitor pain before, during, and after a painful procedure. The list of tools available is extensive and the preceding is only a partial listing. For further information on pain scales and details of each, search the Internet to find the data needed. The Wong-Baker FACES scale (Figure 20-3) has widespread use for patients 3 years of age and older and is particularly useful for adults who have language barriers or who do not read, because they can select the face that best describes their pain. The McGill-Melzack Pain Questionnaire provides descriptive words and phrases that may be used to help the patient communicate the subjective pain experience (Figure 20-4). It is especially useful for individuals who have chronic pain. When possible, chart the description in the patient’s exact words. It may be necessary to seek additional data from significant others. Scales such as the ones shown in Figure 20-5 are often used to assess acute pain. The most common scale used asks the patient to rate the pain being experienced on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (intense or excruciating). The degree of relief for the pain after an analgesic is given is again rated using the same 0 to 10 scale. When different potencies of analgesic agents are ordered for the same patient, the nurse can use this numeric rating data in combination with the other data gathered to determine whether a more or less potent analgesic agent should be administered. Other scales sometimes used include faces depicting facial grimacing, smiles, and so forth. This approach is useful for those with a language barrier. The color scale is similar to a slide rule. The patient selects the hue or depth of color that corresponds with the pain being experienced. The nurse turns the slide rule scale over and a numeric value is identified that can be used to consistently record the patient’s response. Effective pain control depends on the degree of pain experienced. The previously described 0 to 10 scale is a useful way to determine the patient’s level of pain. For a patient with mild to moderate acute pain, a non-narcotic agent may be successful, but a patient with severe chronic pain may need a potent analgesic such as morphine. The route of administration is chosen on the basis of several factors. One major consideration is how soon the action of the drug is needed. The oral and rectal routes have a longer onset of action than the parenteral route. It is sometimes erroneously believed that oral medications are inadequate to treat pain, but they can provide excellent pain relief if appropriate doses are provided. Generally the oral route is used initially to treat pain if no nausea and vomiting are present. The patient may initially be treated effectively with oral medications; however, the rectal, transdermal, subcutaneous, intramuscular, intraspinal, epidural, and intravenous (IV) routes may be required, depending on the patient and course of the underlying disease. Before initiating a pain assessment, assess the patient for hearing and visual impairment. If the person is unable to hear the questions or see the visual aids used to assess pain, any data collected may be invalid. Nurses must evaluate and document the effectiveness of the pain medications given in the patient’s medical record. Record and report all complaints of pain for analysis by the health care provider. The pattern of pain, particularly an increase in frequency or severity, may indicate new causes of pain. The main reasons for increased frequency or intensity of pain are pain from long-term immobility; pain from the treatment modalities used (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy); pain from direct extension of a tumor or metastasis into bone, nerve, or viscera; and pain unrelated to the original cause or the therapeutic modalities used. Note the patient’s general body position during an episode of pain. Look for subtle clues such as facial grimaces, immobility of a particular part, and holding or resisting movement of an extremity. With pediatric patients, facial expressions, squinting, grimacing, and crying may also be used as indicators of pain level and pain relief. Developmental differences influence the pain experience and how children in different age-groups express pain. Realize that just because infants cannot speak does not mean that they do not have pain. Infants may express pain through continual inconsolable crying, irritability, poor oral intake, and alterations in sleep pattern. Preschool children may verbalize pain; exhibit lack of cooperation; be “clingy” to parents, nurses, or significant others; and not want the site of the pain touched—they may actually push you away as you approach the painful area. Older children may deny pain in the presence of peers and display regressive behaviors in the presence of support personnel. In the older adult, it is useful to perform the Katz Activities of Daily Living Measurement and the “get up and go” test to determine the individual’s functional status. What specific measures relieve the pain? What has already been tried for pain relief, and what, if anything, has been beneficial? In the presence of pain, always examine the affected part for any alterations in appearance, change in sensation, or limitation in mobility or range of motion. In older adults, it is particularly important to evaluate the musculoskeletal and neurologic systems during the physical examination. What coping mechanisms does the patient use to manage the pain experience—crying, anger, withdrawal, depression, anxiety, fear, or hopelessness? Is the individual introspective and self-focusing? Does the individual continue to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) despite the pain? Does the individual alter lifestyle patterns appropriately to enhance pain relief measures prescribed? Is the individual able to continue to work? Is the individual socially withdrawn? Is the person seeing more than one health care provider to try to obtain an answer about the origin of the pain or to obtain more pain medication from a different health care provider? Unless contraindicated, moderate exercise should be encouraged. Often, pain causes the individual not to move the affected part or to position it in a manner that provides relief. Stress the need to prevent complications by using passive range of motion. Regularly scheduled exercise is important to prevent further deterioration of the musculoskeletal system, especially in older patients who may also have diminished capacity. To enhance the effects of the medication therapy, use nonpharmacologic strategies such as relaxation techniques, visualization, meditation, biofeedback, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) units. (The patient will require instruction for using each of these prescribed techniques.) Assist with referral to a pain clinic for management of pain, especially chronic pain. • Goals should be established when initiating a treatment regimen. Prevention, reduction, or elimination of pain is an important therapeutic goal. The patient and caregiver(s) should be involved in the establishment of these goals so that outcomes important to the patient are incorporated into the treatment goals, and so that they have realistic expectations. Pain, especially chronic pain, may not be completely eliminated, but must be managed. Additional important goals include improving the patient’s quality of life, functional capacity, and ability to retain independence. Specific therapeutic goals established may include the following: • Pain at rest, <3 on pain scale • Pain with movement, <5 on pain scale • Able to have at least 6 hours of sleep uninterrupted by pain • Able to work at a hobby (e.g., doing crafts, playing cards, gardening) for 1 hour Even though pain medicine administration may be scheduled, encourage the patient to request pain medication before the pain escalates and becomes severe. Encourage open communication between the patient and the health care team regarding the effectiveness of the medications used. Although the smallest dose possible to control the pain is the goal of therapy, it is also important that the dose be sufficient to provide adequate relief. Therefore, the patient must understand the importance of expressing the degree of relief being obtained so that appropriate dosage adjustments can be made. Express understanding, provide diversional activities, and encourage frequent rest periods, especially after the administration of analgesics, antidepressants, and antianxiety medications. The medication profile may list more than one analgesic order for the same patient. This requires the nurse to use judgment in choosing the correct medication for the patient based on pain assessment data collected. The nurse must identify when the last dose of pain medication was administered by checking both the patient’s medication administration record (MAR) and the narcotic control record. It is common practice for analgesics to be ordered intermittently on a PRN basis. However, in the case of chronic pain or intractable pain, it has been found that administering analgesics around-the-clock, such as every 3 to 4 hours, will maintain a more constant plasma level of the drug (steady state), resulting in more effective analgesia. This approach can result in better control of the pain while using less of the analgesic ordered. Many clinical institutions have established policies for pain medications ordered on a PRN basis. These are referred to as range orders. Medication range order policies provide guidelines for the clinical staff to interpret the PRN ranges in the same way. The pain scale assessment is often used as a guideline for the purpose of pain relief range orders. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) has gained acceptance in both the inpatient and ambulatory setting. Pumps are available for inpatient use and in ambulatory units for home or nursing home settings. The PCA method of administration allows the patient to control a small syringe pump containing an opiate agonist, usually morphine, which is connected to an indwelling IV catheter. When initiating the PCA pump procedure, a loading dose is often given to gain rapid blood levels necessary for analgesia. The patient then receives a slow continuous infusion from the syringe pump; this is referred to as a basal rate. Depending on the activity level and level of analgesia needed, the patient may push a button, self-administering a small bolus of analgesic to meet his or her immediate need. A timing device on the pump limits the amount and frequency of the dose that can be self-administered per hour. Additional adjustments of the dosing and frequency may be required as therapy continues. This approach allows the patient to have some control over the pain relief and eliminates the need for the patient to wait for a nurse to answer the call light, check the last dose of analgesics given, and prepare and administer the medication. After discharge from the hospital, this method of administration also allows significantly more freedom of movement for the patient and caregiver. When PCA is used, the nurse should explain the use of the PCA pump to the patient and observe the patient using it to validate understanding. (It also should be explained to the family and significant others.) Record the amount used every 4 hours and notify the pharmacy well in advance of the need for more medication so that it is available when needed. The degree of pain relief achieved should always be recorded. When pain relief is inadequate, assess for other causes and contact the prescriber to discuss a modification of the regimen. PCA pumps are also used for chronic pain; however, the dose can be delivered intravenously or subcutaneously. For chronic pain treatment, the largest dose of the medication is given continuously with demand. Continuous subcutaneous opioid analgesia uses either a butterfly-type needle (25- to 27-gauge) or a special needle device placed subcutaneously into the subclavicular tissue under the clavicle or in the abdomen. The needle should be inserted in the body’s trunk, usually the abdomen, because of diminished circulation in the extremities. Epidural analgesia has long been used in obstetrics but is now recognized as an effective means for controlling acute pain in a variety of postoperative procedures. Epidural analgesia most commonly delivers morphine or fentanyl (sometimes combined with bupivacaine) into the subarachnoid space. It can be administered continuously with an infusion pump, intermittently by bolus administration, or via an implanted port. Nursing responsibilities during epidural analgesia involve the following: Transdermal opioid analgesia uses fentanyl (Duragesic) for relief of chronic pain. It takes approximately 12 to 24 hours for the initial patch of medication to reach a steady blood level, so other analgesics must be used during this time. Once placed, the patch provides relief for up to 72 hours. Intermittent “rescue” dosing may still be needed during the patch use. When terminated, the patient still needs to be monitored for an additional 24 hours because the drug may still be present in body tissues. Some patients will not ask for pain medication, so it is important to intervene and anticipate their needs. Do not make the patient wait unnecessarily for pain medication. The patient should eat a well-balanced diet high in B-complex vitamins and limit or eliminate sugar, nicotine, caffeine, and alcoholic intake. Drinking eight to ten 8-ounce glasses of water daily helps maintain normal elimination patterns. To minimize or avoid the constipating effects of opiates, the patient should increase intake of fiber and fluids. If long-term use of opiates is planned, stool softeners may be necessary. Teach the patient, family, and significant others the benefits of adequate pain control. Work with them to determine their perception of pain management, use of drug therapy, and nonpharmacologic approaches to pain management. If the patient is hesitant about these approaches, determine why. Stress that addiction is not a major factor with short-term use of analgesics, and that during long-term use, such as with cancer, it is not the primary concern. The major issues involved with long-term use of analgesics include obtaining sufficient pain control to provide comfort, ensuring that the patient has ample rest, and enhancing the patient’s quality of life. Inform the patient what medications are available for pain control and when and how to request them. Discuss the patient’s expectations of pain management and how to rate the severity of pain honestly so that the expectations can be met. Ask what level of exercise is attainable without severe pain. Is the pain control adequate for the individual to maintain ADLs or work? Assess changes in expectations as therapy progresses and the patient gains understanding and skill in the management of the diagnosis. In terminal illnesses, increasing pain necessitates careful management. The duration and intensity of the pain should be constantly reported to the health care provider for appropriate modifications of the medication regimen. Assist the patient to learn to cope effectively with the pain. Discuss changes in lifestyle needed to support adequate pain control. Include family members in discussions of pain management. Give praise when techniques are attempted, regardless of whether success is achieved. Teach the patient how to self-administer the analgesics ordered on an outpatient basis. This will include transdermal, transmucosal, oral, and rectal routes of administration and care of infusion ports and central lines. (Be sure to validate and record the degree of understanding of the prescribed pain regimen.) Include social services information in the patient education process, especially how to connect with community resources available for the patient and family. Not everyone has the financial resources to obtain the medicine prescribed. The degree of professional support needed to implement the planned pain control regimen at home must be carefully evaluated. Make sure that the patient and family understand how to obtain assistance with pain medication administration and patient care needs (e.g., visiting nurse, hospice). Throughout the course of treatment, discuss medication information and how it will benefit the patient. Drug therapy for the management of pain should be coupled with comfort measures, relaxation techniques, meditation, stress management, and meeting the total care needs of the individual to ensure maintenance of ADLs. Provide the patient and significant others with important information contained in the specific drug monograph for the medicines prescribed. Additional health teaching and nursing interventions for adverse effects are described in the drug monographs that follow. Seek cooperation and understanding of the following points so that medication adherence is increased: name of medications; dosage, route, and times of administration; and common and serious adverse effects. Enlist the patient’s aid in developing and maintaining a written record of monitoring parameters (e.g., frequency of pain attacks, activity performed when pain occurs, techniques used to control pain, degree of pain relief, exercise tolerance; see Patient Self-Assessment Form for Analgesics on the Companion CD or the Evolve Web site). Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient understands how to use the form and instruct the patient to bring the completed form to follow-up visits. During follow-up visits, focus on issues that will foster adherence with the therapeutic interventions prescribed. The term opiate was once used to refer to drugs derived from opium, such as heroin and morphine. It has been found that many other analgesics not related to morphine act at the same sites within the brain. It is now understood that opiate agonists and opiate antagonists act at the same site as morphine to stimulate analgesic effects (opiate agonists) or block the effects of opiate agonists (opiate antagonists). Another outdated term is narcotic. Originally, it referred to medications that induced a stupor or sleep. Over the past 80 years, it has gradually come to refer to addictive morphine-like analgesics. The Harrison Narcotic Act of 1914, which placed morphine-like products under governmental control, helped promote this association. The development of analgesics that are as potent as morphine but do not have its sedative or addictive properties makes the word narcotic outdated; the terms opiate agonists and opiate partial agonists should be used. Opiate agonists are a group of naturally occurring semisynthetic and synthetic substances that have the capability to relieve severe pain without the loss of consciousness. They act by stimulating the opiate receptors in the CNS. Most of these agents also produce physical dependence and are thus considered controlled substances under the Federal Controlled Substances Act of 1970. These agents can be subdivided into four groups: morphine-like derivatives, meperidine-like derivatives, methadone-like derivatives, and an “other” category (Table 20-1). Administration of these agents causes primary effects on the CNS (e.g., analgesia, suppression of the cough reflex, respiratory depression, drowsiness, sedation, mental clouding, euphoria, nausea and vomiting); there are also significant effects on the cardiovascular system and gastrointestinal (GI) and urinary tracts.

Drugs Used for Pain Management

Objectives

Key Terms

) (p. 310)

) (p. 310)

) (p. 310)

) (p. 310)

) (p. 310)

) (p. 310)

) (p. 310)

) (p. 310)

) (p. 310)

) (p. 310)

) (p. 310)

) (p. 310)

) (p. 311)

) (p. 311)

) (p. 311)

) (p. 311)

) (p. 311)

) (p. 311)

) (p. 311)

) (p. 311)

) (p. 311)

) (p. 311)

) (p. 311)

) (p. 311)

) (p. 311)

) (p. 311)

) (p. 312)

) (p. 312)

) (p. 312)

) (p. 312)

) (p. 312)

) (p. 312)

) (p. 312)

) (p. 312)

) (p. 312)

) (p. 312)

) (p. 312)

) (p. 312)

) (p. 312)

) (p. 312)

) (p. 312)

) (p. 312)

) (p. 318)

) (p. 318)

) (p. 320)

) (p. 320)

) (p. 320)

) (p. 320)

) (p. 324)

) (p. 324)

Pain

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

Pain Management

Actions

Uses

![]() Nursing Implications for Pain Management

Nursing Implications for Pain Management

Assessment

History of Pain Experience

Nonverbal Observations.

Pain Relief.

Physical Data.

Behavioral Responses.

Implementation

Comfort Measures

Exercise and Activity.

Nonpharmacologic Approaches.

Medication.

Pain Control.

Nutritional Aspects.

![]() Patient Education and Health Promotion

Patient Education and Health Promotion

Fostering Health Maintenance.

Written Record.

Drug Class: Opiate Agonists

Actions

![]() Table 20-1

Table 20-1

DOSAGE EQUIVALENT TO MORPHINE (10 mg)

GENERIC NAME

BRAND NAME

AVAILABILITY

INITIAL ADULT DOSAGE

DURATION (hr)

IM (mg)

ORAL (mg)

Morphine and Morphine-like Derivatives

codeine ![]()

Codeine Sulfate

Codeine Phosphate

Tablets: 15, 30, 60 mg

Injection: 30, 60 mg

Oral solution: 15 mg/5 mL

PO, subcut, IM, IV

Analgesic: 15-60 mg q4-6h

Antitussive: 10-20 mg q4-6h

4-6

130

200

hydrocodone ![]()

—

Hydrocodone available only in combination with other ingredients for pain (e.g., acetaminophen, ibuprofen) See Table 20-4

—

—

—

—

hydromorphone ![]()

Dilaudid, Dilaudid-HP

Tablets: 2, 4, 8 mg

Liquid: 1 mg/mL

Suppositories: 3 mg

Injection: 1, 2, 4, mg/mL

PO: 2 mg q4-6h

Subcut, IM: 2 mg q4-6h

IV: 1-2 mg q4-6h

Rectal: 3 mg q6-8h

4-5

1.5

7.5

levorphanol ![]()

—

Tablets: 2 mg

PO: 2 mg q6-8h

4-8

2

4

morphine ![]()

Morphine Sulfate

Tablets: 15, 30 mg

PO: 10-30 mg q4h

Subcut, IM: 10 mg/70 kg

IV: 4-10 mg slowly

Rectal: 10-20 mg q4h

4-5; 8-24 for sustained release products

10

30

Morphine Sulfate CR, MS-Contin

Tablets, sustained-release (12 hr): 15, 30, 60, 100, 200 mg

Avinza

Capsules, extended-release beads (24 hr): 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, 120 mg

Morphine Sulfate

Solution: 10, 20, 100 mg/5 mL; 20 mg/mL

Suppositories: 5, 10, 20, 30 mg

Injection: 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 10, 15, 25, 50 mg/mL;

150 mg/5 mL

Morphine sulfate/Naltrexone

Embeda*

Capsules, extended release:

Morphine (mg)/naltrexone (mg): 30/1.2, 50/2, 60/2.4, 80/3.2, 100/4

PO: Start with lowest dosage; dose no more frequently than q12h. Requires individual patient adjustment

12

—

—

oxycodone ![]()

Roxicodone

Tablets: 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 mg

PO: 5 mg q6h

4-5

15

30

OxyContin

Tablets, controlled release (12 hr): 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 60, 80 mg

PO:10-160 mg q12h (controlled-release)

Oxycodone

Roxicodone

Capsules: 5 mg

Oral solution: 5 mg/5 mL; 20 mg/mL

oxycodone with aspirin ![]()

Percodan (with aspirin, 325 mg)

Tablets: 4.8 mg

PO: 4.5 mg q6h

4-5

15

30

oxycodone with acetaminophen ![]()

various

Tablets: 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10 mg plus acetaminophen 300, 325, 400, 500, 650 mg

PO: 2.5-10 mg q4-6h

4-5

N/A

N/A

oxymorphone ![]()

Opana, Opana ER

Tablets: 5, 10 mg

Tablets, sustained release (12 hr): 5, 7.5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40 mg

Injection: 1 mg/mL

PO: 10-20 mg q4-6h

PO: 5-10 mg q12h (sustained release)

IV: 0.5 mg

Subcut, IM: 1-1.5 mg q4-6h

3-6

1

10

Meperidine-Like Derivatives

alfentanil ![]()

Alfenta

Injection: 500 mcg/mL in 2, 5, 10, 20 mL ampules

IV: Variable

>45 min

—

—

fentanyl ![]()

Sublimaze

Injection: 50 mcg/mL

IM: 50-100 mcg

1-2

—

—

Fentora

Buccal lozenges: 100, 200, 300, 400, 600, 800 mcg

Buccal: 200 mcg

1-2

Actiq

Oral transmucosal lollipop: 200, 400, 600, 800, 1200, 1600 mcg

Variable

Duragesic

Transdermal patch: 12, 25, 50, 75, 100 mcg

Upper torso: One patch q72h

72

meperidine ![]()

Demerol

Tablets: 50, 100 mg

Solution: 50 mg/5 mL

Injection: 10, 25, 50, 75, 100 mg/1 mL

PO, subcut, IM: 50-150 mg q3-4h

IV: 25-100 mg very slowly

2-4

75-100

300

sufentanil ![]()

Sufenta

Injection: 50 mcg/mL in 1, 2, 5 mL ampules

IV: Variable

2-3

—

—

Methadone-like Derivatives

methadone ![]()

Methadone, Dolophine

Tablets: 5, 10, mg

Tablets, orally disintegrating: 40 mg

Solution: 5, 10 mg/5 mL

Injection: 10 mg/mL

Oral concentrate: 10 mg/mL

Analgesia:

PO, subcut, IM: 2.5-10 mg q8-12h

Maintenance:

PO: 20-40 mg; up to 120 mg daily

4-8 (may become substantially longer due to variable half-life)

10

20

Other Opiate Agonists

tramadol ![]()

Ultram

Tablets: 50 mg

Tablets, extended release: 100, 200, 300 mg

PO: 50-100 mg

4-6

—

—

100

—

Ultram ER; Ryzolt

Capsules, extended release (24 hr): 100, 200, 300 mg

tapentadol ![]()

Nucynta

Tablets: 50, 75, 100 mg

Tablets, extended release (12 hr): 100, 150, 200, 250 mg

PO: 50-100 mg

4-6

—

— ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

20. Drugs Used for Pain Management

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue