Case 20 A woman with microscopic haematuria

Alice was 56 when she consulted Dr Hendry. She had been feeling nonspecifically unwell with fatigue, poor sleep and headaches. In the course of examining her Dr Hendry found Alice’s blood pressure was 176/100 mmHg. Dr Hendry arranged for Alice to see the practice nurse for three blood pressure checks, blood tests and ECG and urinalysis. Alice’s blood pressure was satisfactory, her blood tests and ECG were normal and urinalysis showed 2+ blood. The practice nurse sent the urine sample off for microscopy and culture and this showed no growth and no cells.

What would you do now?

Alice consulted another partner a few months later. She had malaise and dysuria. Urinalysis showed blood, protein and leucocytes and she was treated for a urine infection. No follow up urine sample was sent. This pattern was repeated a year later.

At the age of 58 Alice underwent an insurance medical and was noted to have 3+ microscopic haematuria.

What would be your differential diagnosis and how would you discriminate between them?

The insurance report was sent to the practice but no action was taken. On her 59th birthday Alice was admitted into hospital with fever, vomiting and left renal colic. She was found to have a left hydronephrosis secondary to a stage 3 bladder cancer.

Alice brought a claim against Dr Hendry and the practice for failure to investigate persistent microscopic haematuria.

Do you think her claim will succeed?

Expert comment

Expert comment

Microscopic haematuria is a difficult condition for general practitioners because it is very common but can indicate serious disease. In the UK the July 2000 Referral Guidelines for Suspected Cancer (the ‘Two Week Rule’ referrals) recommended urgent referral of all patients with microscopic haematuria over the age of 50. In the June 2005 version this was changed to ‘unexplained’ microscopic haematuria.

The difficulty with this is that microscopic haematuria is relatively common and until recently it has been rather poorly defined. A 2003 review in the New England Journal of Medicine found studies quoting prevalence rates that varied from 0.18% to 16.1% (Cohen & Brown, 2003). Older studies suggest that 4% to 7% of the general population will have microscopic haematuria. One 1986 US study found a prevalence of 13% in asymptomatic males and females over the age of 50. On investigation 2.3% of those investigated had serious disease and 0.5% had renal or bladder cancer (Mohr et al., 1986).

More recent guidance has advised that the terms non visible and visible haematuria replace the terms microscopic and macroscopic. Nonvisible haematuria includes dipstick haematuria of more than a trace of blood and red cells detected on urine microscopy. Urinalysis (of 1+ or more) appears to detect levels of haematuria equivalent to 3–5 red cells per high-powered microscopy field (roughly the previous definition of haematuria). It is not necessary to confirm with urine microscopy (Kelly et al., 2009).

Common causes of nonvisible haematuria are menstruation, sexual intercourse and urinary tract infection (UTI). These need to be excluded before any other investigation. Athletes such as long-distance runners get nonvisible haematuria and should probably be re-investigated after three days’ abstention from activities.

Persistent unexplained nonvisible haematuria can be caused by glomerular renal disease (most often IgA nephropathy or thin basement membrane disease) or urological disease such as stones or cancer.

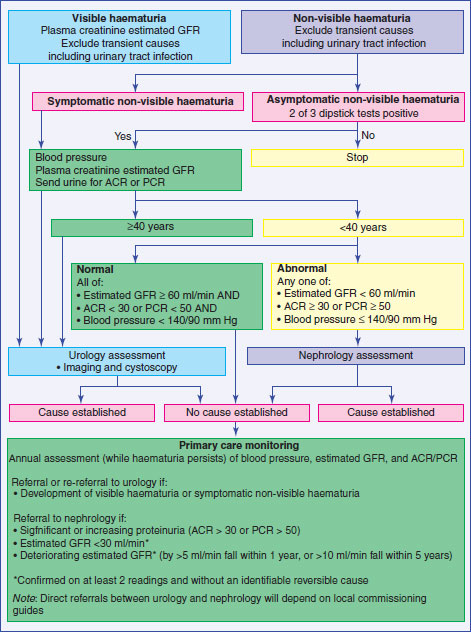

Recent guidance is that nonvisible haematuria in asymptomatic patients should be confirmed on two out of three urinalysis tests before being investigated. After treatment of a UTI with nonvisible haematuria urinalysis should be repeated and investigated if the haematuria is persistent. A 2009 algorithm by Kelly et al. (2009) is reproduced in Case Figure 20.1:

Figure 20.1 Assessment and management of non-visible haematuria in primary care.

Source: Kelly KD, Fawcett DP, Goldberg LC (2009) Assessment and management of non-visible haematuria in primary care. BMJ 388: bmj.a3021.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree