CHAPTER 2. Principles

• Introduction

• The spirit of this approach

• The consulting style

• Change is a journey, not an event

• Importance and confidence as key elements of motivation

• Managing the internal conflict

• The difference between advice and information

• Listening as a key skill

Introduction

This book brings together the field of communication in health care, the study of motivation and how people change, and insights derived from listening to and observing patients and students. The book does not describe a new theoretical model or a specific protocol for consulting about behavior change. Rather, it offers suggestions on how to incorporate the fascinating things we now know about this topic into everyday clinical practice.

It has been said, apparently since Ancient Greek times, that the three basic tools of medicine are ‘the herb’, ‘the knife’, and ‘the word’ (Grant 1995). This chapter is about the use of ‘the word’ in behavior change consultations.

A lot has been written about good general consulting skills, much of which is clearly relevant to talking about behavior change. However, the behavior change consultation presents some unique challenges which make it quite different from, for example, the breaking of bad news to a patient, or the eliciting of a history of presenting symptoms.

This aim of this chapter is to describe the principles upon which the strategies described in the following chapters are based.

The spirit of this approach

We pay a lot of attention to technique and strategy in this book, yet by far the most important aspect is the spirit of the method. Put simply, this is a collaborative conversation about behavior change. Rather than wrestling, as a colleague once put it, it is more like dancing. The patient is encouraged to be an active decision maker. The practitioner provides structure to the discussion (an ‘expert facilitator’), expert information where appropriate, and elicits from patients their views and aspirations about behavior change, helping them to become more aware of what is important to them, and their intentions. This is not merely a matter of using techniques or strategies, but of approaching the consultation and the topic of behavior change with a set of attitudes that promote patient autonomy.

Most of us behave, at times, in ways that compromise our health, and we each have our own notion of what constitutes acceptable risk. Most of the risks we take are for pleasure or some type of benefit, or we wouldn’t do it. Our clinical approach is based on the principle that, in general, people met by practitioners in consultations usually have the freedom of choice to behave as they wish, within the confines of their social and economic circumstances. Seen in this light, the role of the practitioner is to help patients to make an informed choice about whether or not to change their behavior. The practitioner might want to increase the patient’s knowledge of, and access to, healthy options, but their freedom to choose is their fundamental right. Most health-threatening behaviors are, after all, not illegal! If a patient decides to change, it is the practitioner’s role to help them to take effective action based on their choice. It is important to remember that most attempts to change behavior occur naturally, outside of the consultation. We all have experience of this in our own personal lives. Sometimes we succeed, and many times we fail. Many successful attempts only occur after a few ‘false starts’. There is much to be learned from ‘failed’ attempts to change that give people a better chance of changing in the future.

If your work is based on the principle that patients are to have as much autonomy as possible, it is not appropriate to force your views upon them, however much you have their own best interests at heart. This approach is patient-centered but not without a clear structure and focus provided by the practitioner. Also, it does not mean that the practitioner should refrain from providing the patient with a clear, accessible account of the risks (and benefits) of health-threatening behavior. The practitioner’s role is to help patients to make decisions that make sense within their own frame of reference. Your own views as a practitioner are nevertheless highly relevant. You do have knowledge about behavior change, and about which behaviors are associated with optimal health. However, it is the way in which you share your knowledge with patients that is crucial. An appropriate approach to behavior change can be shown thus: What do you feel about your…? How does this fit into your everyday life? I believe that…, but it is your choice, whether to change or not. If you would like to consider change, remember, I am here to help you if you feel you need this.

Sometimes, making decisions to change behavior can have profound effects on patients’ lives. An idea like getting more exercise might seem simple to a practitioner, but in fact can involve a patient changing a lot in his or her life. For example, we have heard a practitioner express frustration that his patients, overweight single mothers, would not take his ‘simple’ advice to take a brisk half hour walk every day. He hadn’t thought (or asked them) about the logistics of going out for even a leisurely walk with a baby in a stroller and a complaining toddler in tow.

Other behaviors might be affected, and the patient might need to examine fears about these changes; for example: Will taking more exercise lead me to havea heart attack? Will giving up smoking make me put on weight? Understanding these issues from the patient’s point of view is crucial to the practitioner’s efforts to promote change. To achieve this, it is necessary to keep close to a basic principle of patient-centered medicine; you must want to understand and value the patient’s perspective. By seeing into the patient’s world, process and outcomes will be improved. This is both a matter of attitude and technique.

It is crucial to respect the autonomy of patients, and their freedom to change or to continue their behavior. Fundamental counseling skills can be used as a device for understanding, and demonstrating respect for, the patient’s views. This is an active, not a passive, process, in which the practitioner tries to empathize with the patient or, in other words, to see the situation from their frame of reference. A patient may come from a different gender/cultural/social background from that of the practitioner, and may have quite different, but equally valid, views and priorities. Conveying respect implies acceptance of whatever decision the patient takes about behavior change.

Assumptions that can, if we are not careful, obstruct our work

Many behavior change consultations fail because the practitioner falls into the trap of making assumptions. Patients are more likely to consider change openly if you avoid imposing these assumptions on them.

1. This person OUGHT to change

This is difficult to avoid, because you place a high value on health, you are concerned for the patient and their family, and often do feel that change would be a good idea. You cannot be dishonest about this but it may not be helpful to express it every time. The solution is either to hold back on giving your views until you understand those of the patient, or to express them openly but not in an imposing manner: for example: I think it is a good idea to change your diet, but what do you really think about this? In other words, you can express your views in a relatively neutral and non-judgmental way, placing emphasis on the patient’s freedom of choice while remaining open to the possibility that change, for them, may have negative consequences of which you are not yet aware. This also emphasizes that it is the patient’s view that matters most. Having a fixed view that the patient ought to change can lead to a judgmental approach seeping through; the patient will then feel at a disadvantage and behave defensively.

2. This person WANTS to change

It is easy to assume that someone whose behavior is clearly making them ill, worsening a condition or putting them at risk will want to change. Turning up at a weight loss clinic or smoking cessation group is often taken to be evidence that people are well motivated to change. There are, of course, many reasons why people attend and many mixed motivations. The assessment of how much the person wants to change will be crucial to the success of the consultation. Remember that patients sometimes feel intimidated by health practitioners; they might not want to be frank because they fear possible disagreement about behavior change or fear being judged. The practitioner’s general attitude and specific wording of questions can help to facilitate honest discussion. The risk of assuming that people want to change, without checking it out, is that of moving too fast into discussion of how they are going to change before they have really made a robust decision that they want to do so. Many are the times that practitioners are into action mode when patients are not yet at the point of deciding to change. Jumping ahead in this way can cause patients to feel misunderstood and badgered, and increase their resistance to change.

3. Health is the prime motivating factor for patients

This is a very common faulty assumption made in consultations. We become entrapped by our own role as caregivers. For example, fairly healthy patients are not necessarily motivated to change behavior in the interests of long-term optimal health. More immediate prospects such as looking better, managing the household budget, or building a career might be more important. Changing behavior has implications beyond health, and not everyone is committed to avoiding poor health for as long as possible at all costs. You are also working in the context of uncertainties. You do not know that a particular overweight man will become diabetic or that his smoker wife will get lung cancer. You do know that their chances of doing so are greater and that behavior change would improve their odds of avoiding these diseases. They will make personal choices whether or not to take that gamble.

Approaches to risk taking are fascinating. It is said that, in the UK, if you buy a ticket for the National Lottery in the last minute before they close the tills, your chance of winning the jackpot (about 14,000,000 to 1) is approximately the same as the chance of you dying before the draw, which takes place 2 hours later. Millions of people buy tickets in the hope of winning, but no one has been heard to say it is not worth buying one as they may not live to see the draw! When we tell patients that 50% of smokers will be killed prematurely by their smoking, some seriously consider those odds worth taking and reinforce this view by recalling all the smokers they know who were in the lucky 50% and died in old age from another cause. Assuming someone is motivated by health concerns can lead you to being blinkered regarding their real concerns, and make it impossible to be patient-centered. Living for a shorter time but doing the things that really bring fulfillment could be what counts most for a lot of people.

4. If the patient does not decide to change, the consultation has failed

This assumption is unrealistic and overambitious. Deciding to change is a process, not an event, and it takes time. People vacillate between feeling ready to take action and feeling unwilling to even think about doing so. Simply helping someone to think a little more deeply about change is a useful outcome of a consultation. A decision to change is more likely to be taken later, outside of the consultation.

Management cultures based on targets put pressures on practitioners to get results. This pressure can get passed on to patients. In reality, it is not within your power to make people change. Thank goodness, the human spirit is too strong; ultimately, people follow their own lights and even the most repressive and controlling regimes have dissidents. You may be right in considering you have failed if you omit to raise important issues with patients and do not give them a chance to think the matter through after taking account of relevant information. It is not within your power, however, to determine the outcome of that process. When you put pressure on yourself to get results, you can be so focused on the desired outcome that you do not pay enough attention to the interpersonal process and do not work as effectively as you might.

5. Patients are either motivated to change, or not

Motivation to do something is not an all-or-nothing phenomenon; it is a matter of degree. Readiness to change varies between individuals and within them over time. In this approach, we have tried to incorporate ways to elicit any little sparks of interest in change from the patient, in the expectation that, over time, these might be fanned into flames. Someone who expresses little interest in change one day might be more interested a few weeks later. Similarly, the person who is really keen and committed one week may lose that enthusiasm later. Both scenarios are normal and to be expected. The issue of readiness to change is discussed in more detail below.

6. Now is the right time to consider change

Choosing the right time is a delicate matter and not always based on rational considerations. There is a common expression to ‘psych yourself up’ for something. All sorts of practical and emotional factors affect people’s willingness to consider change and feeling ‘psyched up’ to do so. The best guideline is the patient’s reactions. If he or she has rushed into the consulting room, late for work after a disagreement at home, you have a problem of timing. Practitioners are used to making quick decisions in their everyday work. It is not helpful to apply this approach (which is highly appropriate in dealing with acute medical problems) to discussion about a patient’s change of lifestyle. Some change issues are urgent, such as HIV protective behaviors. A delay of a day or a week might really be dangerous. Others such as smoking might be, for some people, less urgent although still very important. Choosing the right moment and moving ahead at the right pace will enhance success rates. Moving too fast can lead to patients digging their heels in. Also, working on change in an area other than that prioritized by the practitioner might be the best route to success for the patient. Smoking usually trumps most health-threatening behaviors in terms of adverse effects on health. However, if a patient is not ready to tackle smoking but is ready to consider eating more healthily, smoking could be ‘parked’ for the meantime, and success in the area of eating could breed success later on in quitting smoking.

7. A tough approach is always best

How often have you been encouraged to change by someone who uses a tough approach? People take a hard line when they feel that no other approach is possible. With some patients, on some occasions, being very frank and directly persuasive might be justified and effective, but if we assume this to be necessary for every patient, our efforts will be wasted. Practitioners can enter a vicious circle when they use the tough approach; patients resist (because they do not like feeling cornered), the practitioner feels that they are inherently resistant to change, further tough action appears justified, and so on. A Yes, but… response from the patient is almost a knee-jerk reaction to being told what to do.

8. I’m the expert. He or she must follow my advice

Of course you have expertise. You know what the literature says and have experience of what has worked for other patients in the past. You also understand the physiology of what is happening for the patient. We are not suggesting that practitioners’ expertise is irrelevant, only that your role is to try to help patients to become more and more expert as well. Telling them what to do is unlikely to achieve this. Also, the way in which expertise is used is important. A useful analogy is that of a learner driver who employs a driving instructor. The pupil (or patient) does the driving, and the instructor watches, listens, and encourages, making crucial decisions about where to go, how much information to provide and when to provide it. In consultations about behavior change, the patient should be in control. They need to practice and develop skills in being effective on their own. If we want people to take care of their own health in the long term, it is probably better to support them and offer information so that they can make their own decisions and plans.

9. The approach described in this book is always best

This is a generalization. A lot more clinical and scientific evidence is needed to justify such a statement. Some patients may respond to a much simpler approach, a kind but firm nudge in what you decide to be the right direction. The most successful practitioners are probably not those who stick slavishly to one way of working but who are flexible, skilled in different styles, and sensitive enough to notice when they are doing something that is not helping the patient so that they can stop and do something different. This leads us on to discussion of the different consultation styles we use.

The consulting style

A patient- or client-centered method has been constructed in many fields, for example, in psychology, nursing, and medicine, where there is no shortage of evidence about the importance of taking into account the patient’s perspective when making decisions about treatment and behavior change.

Among the most well-developed statements of the patient-centered method is that provided by Stewart et al (2003):

• Assessment is when the practitioner actively seeks to enter into the patient’s world to understand his or her unique experiences of illness. The practitioner explores the patient’s ideas about illness, how the patient feels about being ill, what he or she expects from the practitioner, and how the illness affects the patient’s functioning.

• Ideas about disease (abnormal pathology) and illness (the patient’s experience of being unwell) are integrated with an understanding of the whole person in a broader context.

• Finding common ground involves both the patient and practitioner working together to define the problem, establish the goals of management, and to be clear about the roles expected of the practitioner and the patient.

• Each contact between the practitioner and the patient is seen as an opportunity for health promotion.

• Each contact is an opportunity to develop a therapeutic relationship between the practitioner and the patient.

• Throughout, the practitioner is realistic about resources (including time and his or her own emotional energy).

Research support for the effectiveness of various elements of the patient-centered method includes demonstration of improved quality of the processes of care, increased patient satisfaction after seeing the practitioner, improved compliance with medication, reduction of patients’ concerns, improved functional status, reduced use of tests, reduced use of emergency rooms and hospital admission, improved blood pressure control, improved postoperative recovery, reduction in blood sugar and improved well-being among people with diabetes (see Orth et al 1987, Kaplan et al 1989, Kinmonth et al 1998, Stewart et al., 2000 and Stewart et al., 2003, Epstein et al., 2005 and Epstein et al., 2007, Hsiao and Boult 2008).

The strengths of the patient

A subtle and powerful difference in your attitude starts to emerge as you encourage patients to harness their own ideas about behavior change; you find yourself working with their strengths rather than their weaknesses! You feel less like a problem- and pathology-seeker, and more like a facilitator of their motivation to change.

One example of where this attitude is well expressed is in the delivery of the Nurse Family Partnership project (see www.nursefamilypartnership.org). Here, an evidence-based program for young pregnant women is based on the fundamental principle that nurses work with the strengths and aspirations of the mothers; discussion of behavior change fits into what they want to achieve more broadly for themselves and their babies.

A more refined discussion of this topic can be found in the work of Dr Grant Corbett, who makes the distinction between ‘deficit’ and ‘competence’ worldviews. Within a deficit view, the patient is seen as missing things (knowledge, attitudes, and skills) that the practitioner must rectify by filling in the gaps. Within the competence view, the patient is seen as someone with knowledge, attitudes, and capabilities that the practitioner draws on as the primary focus for talk about behavior change (Corbett 2006).

Patients sense your attitude towards them, and respond accordingly. A genuine belief in their competence runs far deeper than being nice to them, or even in trying to encourage them. It forms the very basis of the healing powers that you have to promote change, and it is infectious! Change will be more likely if you adopt a view of your patients as competent people facing tricky choices, via which they can make settled decisions.

Following, directing and guiding

Rollnick et al (2008) discuss three communication styles used in healthcare consultations: following, directing, and guiding. Each reflects a different way of looking at the relationship between a practitioner and a patient, and each offers the patient a different sort of help.

Following entails listening attentively to what the patient has to say about the issue in order to understand, as well as possible, their viewpoint. The patient leads the process and owns the agenda.

Directing is the process of telling people what they should do (with or without an explanation of why). When in a directing mode, we are working on the basis that we know best what should be done and how the patient should do it. The patient is expected to listen and comply.

Guiding is accompanying someone on their journey towards change, offering expert knowledge where appropriate. It is gentler than direction and the patient has more autonomy. There has been a prior agreement regarding the agenda or destination, and the patient has consented to be guided in this direction.

All three styles are valid and useful in certain circumstances. Most healthcare practitioners have skills in using all three styles and use a different balance depending on their role and preference. In hospice work and bereavement counseling, following might be a dominant style as people are helped to come to terms with heartbreaking situations and find their own way through the dark times. In accident and emergency room work, a lot of appropriate directing might be heard as patients are told to keep still, hold your arm out, swallow this, while a crisis is managed. In health promotion consultations, guiding is probably the most useful style as patients are helped to work out whether behavior change would feel worthwhile to them, and how they could accommodate it in their lives.

A man who has had a heart attack is likely to be helped by each of these styles at different points, even within the same consultation. In the initial crisis when he is very frightened and does not know what to do to stay alive, he may be grateful for and comply with paramedics and emergency room staff’s direction, trusting that they know best. Later, he may benefit from the following style of a nurse or hospital chaplain helping him talk through this brush with death and its meaning for him. Even later, a cardiac rehab dietitian might be able to help him, using a guiding style to work through the changes he might consider making to his diet.

Writers on concordance (Marinker & Shaw 2003) have discussed similar ideas in the context of compliance with medication for long-term conditions. Traditionally, a role akin to directing has been taken by prescribers and they have been repeatedly frustrated that patients do not take the medicines that evidence tells us would help. Concordance refers to the creation of an agreement that respects the beliefs and wishes of the patient, and not to compliance – the following of instructions (Marinker & Shaw 2003).

The approach described in this book has most in common with guiding or concordance. It acknowledges the practitioner’s expertise while deeply valuing the patient’s input.

Change is a journey, not an event

There has been much interest over the last 25 years or so in exploring what leads up to someone making a change, and the factors affecting whether or not they maintain the change or revert back, eventually, to old habits.

The decision to stop smoking is, of course, always revocable. Once the smoker has embarked on an attempt to quit, he or she is repeatedly faced with another decision, namely whether to persevere with the attempt or abandon it (Sutton 1989, p. 66).

For most of our patients, changing a health-related behavior is an ongoing process with which they need continuing support. A lot of thinking often goes on before they even make the first attempt to change, and maintaining change can remain a struggle for months or years.

In working on this approach, we reviewed the literature on health psychology and behavior change. Some themes stood out very clearly. First, the idea of readiness, derived from the stages of change model (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983 and Prochaska & DiClemente, 1986, DiClemente & Prochaska 1998), was a useful starting point for understanding motivation and how best to work with patients. Depending on their degree of readiness to change, they have different needs and it makes sense to respond accordingly.

Second, standing out from the different models of behavior change, many of them overlapping and in apparent conflict with one another, were two concepts, importance and confidence, which helped to explain a patient’s degree of motivation or readiness to change. They appeared in different guises in different models, but seemed to point to the same conclusion; if a change feels important to you, and you have the confidence to achieve it, you will feel more ready to have a go and be more likely to succeed. When we are sitting in front of patients, understanding their feelings about these three topics will take us to the heart of the complex forces that surround the topic of behavior change.

Readiness to change is a state of mind that reflects the outcome of quite a lot of psychological activity. For example, Joe keeps ‘forgetting’ to renew his gym membership, Kim keeps his membership up-to-date and his gym bag in the back of the car but rarely finds time to go, and Grenville makes excuses to leave work early so as to catch the late afternoon cardio class. They differ in their readiness to follow an exercise program.

Looking at how readiness varies in your work with patients is a useful starting point. Of course, you will want to know why, in the above examples and many others, differences in readiness arise. The concepts of importance and confidence should help with this task and we will discuss these below. To begin with, however, we have been struck, like many other practitioners, by the value of simply being aware of this fluctuating and sometimes conflict-ridden state of mind, readiness. It has clear implications for how we speak to people, whatever debate there might be about other aspects of the stages of change model (Davidson 1998, Prochaska & DiClemente 1998, Wilson & Schlam 2004, West 2006).

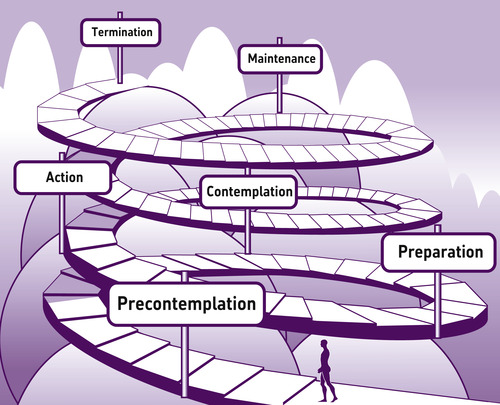

The transtheoretical stages of change model is an attempt to describe readiness and how people move towards making decisions and behavior change in their everyday lives. Its emergence in the field of health promotion and behavior change, which one commentator described as akin to the discovery of a new planet in astronomy (Stockwell 1992), clearly struck a chord with practitioners and researchers alike. People, whether they are patients, practitioners or the public at large, were described as moving through a series of stages when trying to change behavior, from precontemplation through to action and maintenance, along the lines illustrated in Figure 2.1. A thorough attempt was also made to describe the process needed to move from one stage to the next, and the therapeutic techniques likely to engage these processes. An overview and critique of this model can be found in Miller & Heather (1998).

|

| Figure 2.1 The stages of change model. From Prochaska, Norcross, Di Clemente: Changing for good, 2nd edition (William Morrow & Co, 1994), with permission. |

If we take the example of smoking, which was used in much of the research on this model, someone in the precontemplation stage can be expected to think and feel quite differently from someone in the preparation stage. While the former will not be actively thinking about stopping smoking, the latter will be planning very actively. Between these two people lies the person in the contemplation stage, who thinks about stopping, wants to do something about it, but also does not. It is common for smokers to fall into this stage. The model states that people are likely to move through these stages in the cyclical manner depicted in Figure 2.1. The model, originally drawn as a circle, was later drawn as a spiral to demonstrate that, on relapse, people do not necessarily go ‘back to square one’, but have the potential to learn from it and continue the journey onward and upward.

This model describes what happens to people as they change in everyday life with or without professional help. If we turn our attention to how one helps people who vary in their states of readiness, the usefulness of the model as a conceptual framework is striking; people have different needs and they do not all respond well to the same kind of help. Unfortunately, in the past, too many services have been action oriented, revolving around the small percentage of people who are ready to come forward and take action, typically less than 20% (DiClemente & Prochaska 1998). The appeal of this model to practitioners probably does not lie in the precise definition of stages or the intricacies of stage-specific interventions, but in the provision of general guidance; for example, if someone is not ready to change, action talk will be counterproductive. If this observation of the reason for its popularity is correct (see Rollnick 1998), unresolved issues such as whether or not stages exist and how to match interventions to stages might not be critically important for the present purposes.

The model provides a unifying concept, readiness to change, which is so clearly relevant to everyday practice that we should be able to use it as a platform for approaching behavior change.

In the context of substance misuse, that examination of the model helps researchers understand the larger processes of change where addict and treatment provider meet (DiClemente et al 2004, p. 103).

In a more everyday context, a colleague described the model’s usefulness as being similar to our understanding of the seasons. We cannot precisely determine when winter begins and we can be surprised by a warm winter’s day or a cold snap in summer, but the concept is still useful for deciding when to get the winter clothes out or get the garden furniture out of storage.

The challenge for practitioners is to maintain parity or congruence with the readiness to change of the individual. What happens when we fail to achieve congruence, when we talk in a way that is not suited to the readiness of the patient? If we talk to a patient who is not thinking about change as if he or she is ready for action and keen to get as much help as possible, we will encounter resistance. Jumping ahead of the patient’s readiness can be a risky activity. Resistance is discussed in more detail below.

For some years now, the stages of change framework has stimulated research and clinical development across a wide range of fields. Of particular interest are issues that revolve around the use of the stages of change model by practitioners to provide the rationale for intervention. The problem here is that making judgments about readiness, particularly if one is wedded to using stage labels, can be complex and have unfortunate, sometimes unintended, consequences. At best, these judgments are the outcome of genuine consensus between the practitioner and the patient. At worst, they can be oversimplified and driven by the prejudices of the practitioner. Four of the most commonly encountered difficulties are discussed below.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree