CHAPTER 2. Concepts and Theory of Forensic Nursing Science

Virginia A. Lynch

The Science of Forensic Nursing

Among scientific disciplines, forensic nursing represents a departure from the traditional foundations of nursing practice while adding a new dimension to the forensic sciences. Forensic nursing science has evolved in response to the needs of a world in crisis. This emerging discipline should be viewed as an integral member of the multisectorial structures that make up a field of inquiry that applies clinical and scientific knowledge to questions of law in both civil and criminal investigations.

The science of forensic nursing has two foci:

1. The legal principles. This focus relates to evidence collection and reliability, chain of custody and security, and the healthcare provider role in judicial processes.

2. The establishment of the manner of injury and cause thereof. This element includes death, health system documentation, investigation of trauma, care of detainees, and rehabilitation of those who have suffered violence.

Science is defined as an accumulating body of knowledge. A scientist is one learned in science, especially one active in some particular field of investigation (Dorland’s Medical Dictionary, 2005). The forensic sciences refer to any aspect of science as it relates to law. Forensic nursing science is consistent with these other disciplines. The primary area of practice and research inquiry for the forensic nurse scientist is human trauma, both physical and psychological. The incorporation of existing bodies of knowledge with new scientific discoveries has provided a sound foundation for evidence-based forensic nursing practice.

Among other sciences incorporated in the study of forensic nursing are human anatomy and physiology, physical sciences, engineering, social and behavioral sciences, and biomedical sciences including chemistry and physics. Forensic nursing is a theory-guided and ethics-guided practice that requires an intellectual endeavor within its own distinctive knowledge base, experiences, purposes, and values. Contemporary social conditions involving human violence and abuse have shaped the evolution of forensic nursing education, holistic practice, and scientific research to provide a unique framework for the investigation of issues concerning healthcare and the law.

Violence-related trauma is central to the role of the forensic specialist in nursing (Lynch, 1990). Whether physical, sexual, or psychological, violence remains the single greatest source of loss of life and function worldwide (Reiss & Roth, 1993). Forensic nursing assumes a mutual responsibility with the forensic medical sciences and the criminal justice systems in concern for the loss of life and function because of human violence and liability-related issues.

The forensic nurse, as a clinical investigator, represents one member of an alliance of healthcare providers, law enforcement agencies, and forensic scientists involved in establishing a holistic approach to the evaluation and treatment of crime-related trauma. Forensic nurse investigators address relevant areas in the assessment of criminal violence, abuse, and data collection for establishing hypotheses about the interrelationship between healthcare and the law. Forensic nurses fill voids by accomplishing selected forensic tasks concurrently with other health and justice professionals and by establishing themselves as uniquely qualified clinicians who blend biomedical knowledge with the basic principles of law and human behavior (Lynch, 1991).

Theoretical Foundations

As nursing history delineates the principles and philosophies of nursing in general, it also addresses those of forensic nursing, which parallel traditional nursing care in all specialties within the scope and boundaries of nursing practice. Forensic nursing brings to each nursing specialty specific strategies and considerations for meeting the biological, psychological, social, spiritual, and now legal dimensions of patient care in a humanitarian, holistic, and pragmatic orientation. The theoretical perspectives for forensic nursing practice derive their broad construct from several mainstream nursing theories, including those presented by Paterson and Zderad, 1998, Conway and Hardy, 1988, Leininger, 1995, Giger and Davidhizar, 1991, Chinn and Kramer, 1995 and Brenner, 1984.

These nursing theories become integrated within the theories of sociology and philosophy, such as the theories of Mead (1934), Plato (427-347 B.C.) and those explored by Farrell and Swigert (1982), to design an integrated practice model for forensic nursing, as philosophers, sociologists, and others have focused on the construction of practice theory in nursing. Forensic nursing integrates their theories into a framework that helps to describe and explain phenomena specific to forensic nursing science. This common connectedness unites the philosophies of physical science with the legal dimensions and defines forensic nursing’s body of knowledge based on shared theories with other disciplines.

Assumptions applied and defined

Assumptions are statements accepted as given truths without proof. Assumptions set the foundation for the application of a particular theory. Central to the forensic nursing theory is the assumption that integrating disciplines of social science, nursing science, and the legal sciences involves the notion that the multiskilled forensic nurse benefits the patient, the healthcare institution, society, the law, and human behavior.

Truth

Truth is the mantra of the forensic sciences and central to the field of all scientific investigation. Truth explains the objective methodology of forensic sciences applied across a broad base of disciplines and facilitates the collective search for the truth. Reforms in criminal justice systems have come about through advances in DNA technology that have sustained truth and justice in cases where justice had been denied. The Innocence Project was founded in 1992 to determine the truth as it relates to the exoneration of incarcerated prisoners through postconviction DNA testing. It cannot be overemphasized that the forensic nurse is not a victim advocate but rather a patient advocate. The patient, however, may be the accused, a convicted felon, the condemned, or the victim. A forensic nurse is required to remain essentially unbiased and value neutral in all matters—an advocate for truth and justice. Objectivity and neutrality are essential values in the care of forensic patients. The role requires an incisive comprehension of fundamental medicolegal issues as well as the ability to prepare and present testimony in a court of law. It is the search for truth.

Truth, as the central implicit assumption to all forensic investigations, brings enlightenment to unknown, unanswered, and questioned issues related to the origin and manifestations of pathological conditions that affect the person, environment, health, and nursing. The philosophy of forensic nursing practice is based on an ancient philosopher’s love of truth (Plato, 347 B.C.). Without the discovery of truth, diagnosis, treatment, evaluation, rehabilitation, recovery, and prevention would be precluded. Without truth, reconciliation and justice are denied.

Research is an essential element for further developing the concepts, theories, and models of care that apply to forensic nursing. Research initiatives and clinical inquiries form the basis of evidence-based practices (Brenner, 1984). Yet research requires appropriate theoretical frameworks for practice, advanced nursing preparation, competency-based training, and experimental work-based academic development to move out of the shadows and forward into the pursuit of truth.

Paradigms, theories, and ways of knowing

Central to all nursing theories is the assumption that human beings are made up of various dimensions and that each dimension relates to health and well-being. Forensic nursing theory incorporates the human dimensions pertinent to all nursing theories of care, yet it projects beyond the aspects of bio-psychosocial spiritual and cultural beings to introduce and incorporate a dimension of laws. Laws that portend to govern human behavior and social needs represent the direct correlation among the human dimension, health, and well-being. Culture can advance or limit the human dimension. Cultural change can be seen as social learning. Cultural care and cultural interventions are essential components of the forensic and clinical investigation of trauma.

Forensic nurse examiners utilize Carper’s fundamental patterns of knowing in their practice with a variety of models and theories (Carper, 1978). Patterns of fundamental knowing consist of those described as empirical knowledge, aesthetic knowledge, personal knowledge, and ethical knowledge. Other nursing theories and models are symbiotically intertwined and functionally applicable to forensic nursing science.

Components of theoretical concepts

The following components are typically addressed in any theoretical concept of nursing practice: (1) role clarification, (2) role behavior, and (3) role expectation.

Role clarification identifies shared knowledge and skills. It establishes explicit expectations and boundaries between the role of the self and that of others, and it delineates goals as well as costs and rewards associated with enacting them. Role clarification also demonstrates the extent to which significant others reinforce or validate role behavior via complementary and counter roles.

Role behavior is the performance or enactment of differentiated behavior relevant to a specific position. Role expectation is the obligation or demands placed on the individual in a role position. It encompasses the specific norms associated with the attitudes, behaviors, and cognition required and anticipated for a role occupant.

A major component of the integrated model for forensic nursing is interactionism. The focus of interactionism concerns specific links or associations among persons, environment, concern for persons, social integration, development of meaning, and the integration of persons in a social context, as well as processes engaging persons. Not all social systems generate a sense of community, but those that do create a shared culture and social order among their members. Patient advocacy recognizes healthcare as a primary source of physical and emotional stability to the physically or psychologically traumatized patient. Patient advocacy, an aspect of social behavior that protects and provides patients with an emotionally supportive community, serves as one platform for the forensic nurse examiner role. The understanding and explanation of social order as community is the goal of social sciences. This includes the understanding and explanation of criminal behavior and human violence. It focuses on individuals involved in a reciprocal social interaction as they actively construct and create their environment through a symbiotic interaction. The main focus of this perspective reinforces the need for social order and interdisciplinary coordination in healthcare delivery and the social justice sciences.

Problematic social situations, such as the escalation of trends in criminal violence, demand new interpretations and new lines of action, which reinforce the need to continually redefine the role of the forensic nurse. This parallels the major focus of forensic nursing as it deals with change, dynamics, and the processes by which individuals creatively adapt to a society in flux. The ongoing problems in society and rapid social change place new demands on public service providers. Their role behaviors, in turn, quickly generate new and valid concepts that contribute to safe, effective patient care.

A dynamic role of the forensic nurse examiner has evolved in clinical and community nursing practice; it facilitates specialized and unique behaviors in forensic nursing. This role helps nursing, medical, social, and legal systems to clarify questioned issues in response to the epidemiology and query of murder, suicide, sexual assault, abuse, neglect, intentional trauma, communicable disease, and violent criminal acts that threaten lives. The principle of reciprocal social interaction represents the multifaceted relationships among patient, clinician, and multidisciplinary team members that involve law enforcement agencies, social services, legislative authorities, judicial systems, and healthcare operatives. The reciprocal interaction of interagency coordination and cooperation works to improve the structural and functional management, delivery, and effectiveness of services offered by health and justice institutions.

Assumptions of the theory

This theoretical framework makes the following assumptions:

• Clinical forensic nursing is a relatively new science, and there is limited awareness of this specialty on behalf of health professionals, law enforcement agencies, and forensic science practitioners, as well as healthcare consumers.

• Evolving healthcare systems ultimately require changes in the role of the professional nurse.

• The conception and perception of the clinical forensic nurse is currently evolving and developing and at times is poorly defined.

• The application of clinical forensic science is appropriate for the practice of nursing.

• The registered nurse, qualified by education and experience in a broad range of nursing specialties, is capable of identifying role behaviors of the clinical forensic specialist.

• Human rights are a priority for most members of society.

• Forensic nursing care encompasses a sensitivity to differences among culturally and ethnically diverse populations.

• Truth is the central goal of forensic investigative analysis, which involves patient history, assessment of forensic implications, and correlation with the conditions and circumstances of injury, illness, or death.

• Forensic patients hold equal rights in terms of law and ethics, whether victim, accused, or offender.

Propositions

Propositions are ideas brought forward for consideration, acceptance, or adoption. The basic propositions considered in the formation of forensic nursing theory include truth, presence, perceptivity, and regeneration. These propositions are explained as follows:

• Truth. The central force in the resolution of questioned issues that involve the physical, psychological, and social health or ills of a human population; includes past and future truths.

• Presence. The invisible quality that commands and comforts while directing attention away from one’s self and into the being of another, instilling confidence and respect in the self of that being.

• Perceptivity. The investigative tool of one who explores human behavior, awareness of the elements of one’s environment, and sensory phenomena interpreted in light of lived experiences that guide intuitiveness.

• Regeneration. A value and a goal of the advanced forensic praxis in patient healing that affects a victim or offender who has experienced the deepest wounds of the soul; becoming once again as before.

Application of propositions

Care that incorporates the nursing process—assessment, planning, intervention, and evaluation, to restore and promote health in the patient throughout the forensic process—is essential. The concepts of truth, presence, perceptivity, and regeneration will guide the forensic practitioner in the ways of knowing, patterns of being, and shared intuition between patient and practitioner.

The objectives of forensic nursing intervention are injury/illness/death assessment, objective documentation, the collection and preservation of forensic data and evidence, and the prevention of potential psychophysical/psychosocial/psychosexual health risks. Patient empowerment is also a significant issue, consequential to the criminal trauma, healthcare interventions, and the acceptance or rejection by society regarding the circumstances of the criminal act involved, regardless of the patient’s legal status.

Theoretical Components of Forensic Nursing

The theoretical support for forensic nursing care involves the biological, psychological, social, spiritual, and legal dimensions of the nursing practice. Forensic nursing is holistic in nature, addressing these concepts individually and collectively. The science of forensic nursing has been recognized by the professional bodies of nursing that direct the development of nursing education, research, and practice. Forensic nursing theory identifies interconnectedness with theories of the legal and physical sciences, which is reflected in The Joint Commission (TJC) guidelines that provide regulatory direction for healthcare practitioners (TJC, 2009).

These guidelines regard the identification of crime victims and the recovery and documentation of evidence, as well as the procedures for reporting abuse or suspicious patient behavior to a legal agency, as the foundations of forensic nursing practice. The legal sciences define and delineate the parameters of the law responsible for the behaviors of the nursing professional. Forensic nursing behaviors involve, among others, the identification of crime-related injury, the collection of evidence, the reporting suspicion of illegal acts to a legal agent, and the abuse or death of patients in custody or that of incarcerated or institutionalized persons. It is, then, the respective dimensions of the health and justice disciplines that integrate a variety of multidimensional theories into nursing practices and define the distinctive conjectures of forensic nursing science.

Descriptive Theory

In the clinical environs, this role is defined as the application of clinical and scientific knowledge to questions of law related to the civil and criminal investigation of survivors of traumatic injury and patient treatment involving court-related issues (Lynch, 1995a). It is further defined as the application of the nursing process to public or legal proceedings, as well as the application of the forensic aspects of healthcare in the scientific investigation of trauma or death-related issues involving abuse, violence, criminal activity, liability concerns, and traumatic accidents (Lynch, 1991).

Prescriptive Theory

Nurses have always been expected to care for crime victims, patients in legal custody, and victims of traumatic accidents and other liability-related injuries. However, in the past, there has been no specialty role or explicit education to ensure that these legal responsibilities were reasonably met as a component of nursing care. The complex legal needs of the patient were often in jeopardy because of the ignorance of forensic issues by the emergency medical response team and the nurse or attending physician. Investigating officers generally depended on the nurse or physician to accurately document injury and to recover evidence. Without specialized knowledge, neither objective was fulfilled. Complex recovery of evidence, specificity in documentation, and managing emotionally traumatized patients concurrently with life-saving intervention require separate roles for those who provide emergency intervention and those who provide forensic services.

The introduction of a forensic clinician in nursing is healthcare’s direct response to violence. This new discipline was intrinsic to the role nurses fill in the challenge to address the legal issues pertaining to forensic healthcare and to reduce a previously recognized injustice to society. As nurses acknowledged their role in the health and justice movement, they recognized crime-related issues as justifiable elements for healthcare professionals to integrate into their specialty-oriented practice models. They accepted the challenge to reach beyond the immediate treatment environs into the often-shadowed areas of legal issues surrounding patient care. The concept of an integrated practice model in forensic nursing science has initiated an accomplished clinician, cross-trained in the principles and philosophies of nursing science, forensic science, and criminal justice. The recognition and management of medicolegal cases require healthcare professionals to reconceptualize the nursing practice and its body of knowledge.

Patient care now requires a consideration of legal and human rights as well as an awareness of the greater connection the healthcare delivery system has to other social systems. It is no longer acceptable for the healthcare system to exist in isolation, ignorant of the wider world of interfacing systems.

Practice theory

An integrated practice model for forensic nursing science incorporates a synthesis of shared theory from a variety of disciplines including social science, nursing science, and the legal (forensic) sciences. It presents a global perspective on interrelated disciplines and bodies of knowledge that affect forensic nursing practice through social justice. The aspects of a multidimensional theory are activated in the investigation of injury, illness and death, socio-cultural crime, and liability-related questions. An integrated practice model is especially relevant to the applied health sciences.

An Integrated Practice Model

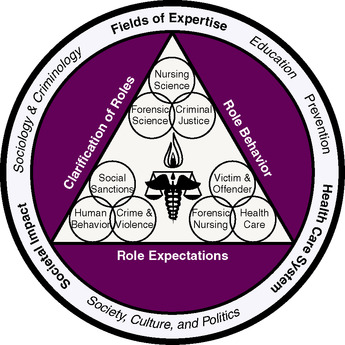

Figure 2-1 illustrates the dynamics symbolized in the following conceptual framework. Forensic nursing science and its humanitarian perspective have the potential to provide new solutions to problems that require a unique multidisciplinary approach. Forensic nursing is a critical component for minimizing the devastating impact of prevalent social and cultural problems in the twenty-first century. It provides a strong theoretical knowledge base for interactional analysis and its prevailing approaches to role development.

Description of the integrated practice model

The model is described as follows: Three principal components embracing the outer triangle constitute the theoretical basis of forensic nursing. The interlocking circles indicate interconnected, interagency coordination, cooperation, and communication essential to public health, safety, and social justice.

• A knowledge base of interrelated disciplines (fields of expertise)–nursing science, forensic science, and the law—use sociological, criminological, and nursing theory to connect role behaviors with the societal consequences of health and human behavior.

• The societal impact components are human behavior (broadly based sociological and psychological notions), social sanctions (legal and institutional sanctions and processes), and crime and violence (both recognized and hidden). Social, cultural, and political factors bring together role expectations within a system of roles.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access