Section 2 Assessment and investigations of a child

2.1 Identification of problems and scoring systems

Early warning scoring (EWS)

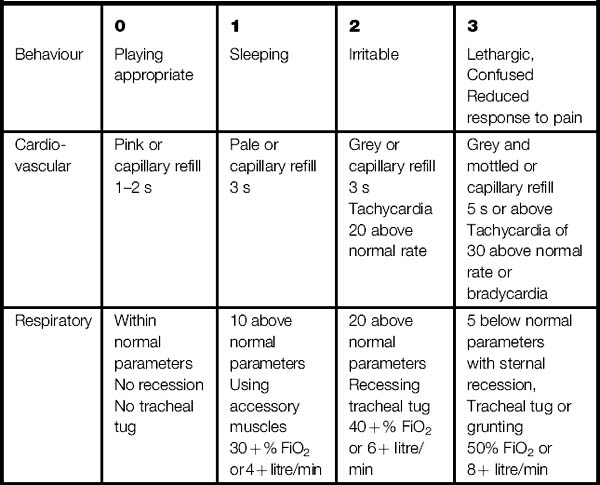

Combining these with observations of the airway, breathing and circulation (ABC), measures of fluid balance and neurological status forms the basis of this simple system of early detection. Deviations from the normal score points allows a total to be calculated (Table 2.1). A total score of 3 or more generally results in the patient’s condition being reviewed by the nurse in charge or the ward medical staff and help sought from the outreach team or medical emergency team (MET) if appropriate.

Assessment of a deteriorating child

A standardized assessment for life support practice is now in place when dealing with multiple trauma or cardiopulmonary/respiratory arrest using the ABCDE style approach (see Section 1). This approach can also be used when assessing the deteriorating patient. The aim of this assessment is to halt the deterioration in the child’s condition and prevent cardiac/respiratory arrest.

A = airway

Determine if the airway is clear/obstructed/either:

Determine if the airway is clear/obstructed/either:

Check for the use of the accessory muscles, e.g. neck and shoulders or tracheal tug.

Check for the use of the accessory muscles, e.g. neck and shoulders or tracheal tug.

Observe the pattern of the chest movement and are they expanding symmetrically.

Observe the pattern of the chest movement and are they expanding symmetrically.

B = breathing

Is there any distress observed in the child?

Is there any distress observed in the child?

Check if the respiratory rate is normal for the child’s age range; if this is very high the child will become exhausted very quickly.

Check if the respiratory rate is normal for the child’s age range; if this is very high the child will become exhausted very quickly.

– Palpation of the chest may indicate surgical emphysema.

– Percussion may reveal differences in note:

If oxygen is prescribed then it should be administered immediately.

C = Circulation

Look at the child carefully – are they distressed, pale or cyanosed?

Look at the child carefully – are they distressed, pale or cyanosed?

What is the consciousness level?

What is the consciousness level?

Check fluid balance for documentation of any urine output.

Check fluid balance for documentation of any urine output.

In the initial stage of shock blood pressure is not a good indicator so use:

In the initial stage of shock blood pressure is not a good indicator so use:

Is the pulse bounding (sepsis) or weak (reduced cardiac output)? ECG may be indicated if it is available.

Is the pulse bounding (sepsis) or weak (reduced cardiac output)? ECG may be indicated if it is available.

D = Disability

The priority of ABC is paramount, but rapid assessment of disability now needs to be observed.

Check consciousness level using the AVPU method (alert, vocal stimuli, pain, unresponsive).

Check pupil reactions to light:

• bilateral pinpoint may indicate drug overdose, e.g. opiates, brainstem stroke

• unilateral dilated unresponsive to light indicates brainstem death, cancer lesion or cerebral oedema.

Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) if time (see section on assessment).

E = Examination

Hypothermia – has the child recently been to theatre where loss of body heat may occur?

Hypothermia – has the child recently been to theatre where loss of body heat may occur?

Electrolytes – urea, creatinine, potassium, sodium levels.

Electrolytes – urea, creatinine, potassium, sodium levels.

Fluids – check fluid balance chart over the past few days:

Fluids – check fluid balance chart over the past few days:

GIT – examine patient for any abnormalities:

GIT – examine patient for any abnormalities:

Haematology – clotting factors, haemoglobin, white blood cell count (WBC), full blood count (FBC).

Haematology – clotting factors, haemoglobin, white blood cell count (WBC), full blood count (FBC).

Infection – do not forget to check for:

Infection – do not forget to check for:

Lines – check if they are source of infection/sepsis:

Lines – check if they are source of infection/sepsis:

Medication – check the drug chart:

Medication – check the drug chart:

2.2 Assessment of a child – scoring systems

Developmental assessment

Child development may be grouped into five domains (areas):

1. Physical (physical growth and maturation)

2. Language (ability to speak and use words)

3. Cognitive (the ability to reason, think, perceptions, attention, memory)

4. Psychological/emotional (feelings and emotions)

Early identification of developmental delay and disorders

Children grow and develop through various stages

Children grow and develop through various stages

There are critical time periods when a child is ready to develop a particular skill

There are critical time periods when a child is ready to develop a particular skill

Children develop at different rates, so assess development broadly

Children develop at different rates, so assess development broadly

Assess and document child’s stage of development

Assess and document child’s stage of development

Deviations should be investigated and documented

Deviations should be investigated and documented

Provide support and stimulation for children’s developmental needs.

Provide support and stimulation for children’s developmental needs.

Roles of professionals in developmental assessment

Developmental assessments should focus on five key areas:

Developmental tests and scales

Developmental screening should consist of the following:

Take a detailed history from the parents

Take a detailed history from the parents

Use suitable age-appropriate materials for the assessment

Use suitable age-appropriate materials for the assessment

Create varied and near natural situations for eliciting behaviour

Create varied and near natural situations for eliciting behaviour

Make close observations of the child’s responses

Make close observations of the child’s responses

Combine personal observations with that from the parents

Combine personal observations with that from the parents

Consider quality of performance across the domains

Consider quality of performance across the domains

Monitor child’s progress over time as child may ‘catch up’ if there is a delay evident.

Monitor child’s progress over time as child may ‘catch up’ if there is a delay evident.

Developmental milestones

Developmental milestones for infants 0–6 months

Babies are born with a large collection of reflexes which are physical responses triggered involuntarily by a specific stimulus.

Babies are born with a large collection of reflexes which are physical responses triggered involuntarily by a specific stimulus.

Newborns are light sensitive, can feel pain and seem to prefer the human face.

Newborns are light sensitive, can feel pain and seem to prefer the human face.

At 1 month babies can recognize different speech sounds and can smile.

At 1 month babies can recognize different speech sounds and can smile.

At 4 months, babies can link familiar sounds with objects.

At 4 months, babies can link familiar sounds with objects.

At 5 months babies begin to respond to their name.

At 5 months babies begin to respond to their name.

Developmental milestones from 8–24 months

At 8 months they can sit without support.

At 8 months they can sit without support.

At 8–9 months they begin to crawl on hands or knees or buttocks.

At 8–9 months they begin to crawl on hands or knees or buttocks.

At 12 months they can stand and some can walk. They develop a pincer grip. They can recognize familiar people and turn when their name is called. They can drink from a cup and can hold utensils for feeding.

At 12 months they can stand and some can walk. They develop a pincer grip. They can recognize familiar people and turn when their name is called. They can drink from a cup and can hold utensils for feeding.

When toy falls out of visual field, they look for the toy in the correct place

When toy falls out of visual field, they look for the toy in the correct place

At 18 months they can walk safely, backwards and sideways. Can use delicate pincer grasp to pick up small objects.

At 18 months they can walk safely, backwards and sideways. Can use delicate pincer grasp to pick up small objects.

Developmental milestones from 3–8 years

At 3–4 years can walk and run easily, walk upstairs, and pedal a tricycle. Holds pencil between thumb and fingers. Can draw and name primary colours. Can cut paper with scissors. Can sing nursery rhymes and enjoys doing jigsaw puzzles.

At 3–4 years can walk and run easily, walk upstairs, and pedal a tricycle. Holds pencil between thumb and fingers. Can draw and name primary colours. Can cut paper with scissors. Can sing nursery rhymes and enjoys doing jigsaw puzzles.

At 5–8 years can ride a bicycle easily, undress and dress self, balance, skip, climb, play ball games and dance.

At 5–8 years can ride a bicycle easily, undress and dress self, balance, skip, climb, play ball games and dance.

Growth and development

Infants grow very quickly in the first year of life, adding 20–30 cm to their height and doubling their birth rate by the age of 5 months (Table 2.2A). There is a rapid increase in size by the age of 2 years. From 2 onwards the child usually gains about 5–7.5 cm in height each year and approximately 3 kg in weight per year. Weight has a similar growth curve to height (Table 2.2B). When the child reaches adolescence, usually from 10 years onwards, there is a rapid growth in height, called a ‘growth spurt’. The hands and feet grow to full adult size earliest, followed by the arms and legs, and the trunk. Children will grow at different rates depending on genetics, nutrition, environment and illness conditions. So these are broad parameters which are a guide to assessment of growth and development.

Table 2.2 Height and weight gain by age

| A Height gain by age | |

|---|---|

| Age | Height |

| Birth–6 months | 2.5 cm per month |

| 6–12 months | 1–5 cm per month |

| 12 months–4.5 years | 7.5 cm per year |

| B Weight gain by age | |

|---|---|

| Age | Weight |

| Birth–6 months | 140–200 g per week (doubles by end of 5 months) |

| 6–12 months | 85–140 g per week (triples by end of 1 year) |

| 12–4.5 years | 2–3 kg per year (quadruples by end of 2.5 years) |

Measuring growth

To measure an infant’s length, the infant is placed supine on a measuring board with the head firmly at the top of the board and heels at the foot of the board.

To measure an infant’s length, the infant is placed supine on a measuring board with the head firmly at the top of the board and heels at the foot of the board.

To measure a child who can stand, use a wall-mounted stadiometer. Remove footwear and ask child to stand tall, with head in the mid-line and child looking straight ahead (parallel to the floor).

To measure a child who can stand, use a wall-mounted stadiometer. Remove footwear and ask child to stand tall, with head in the mid-line and child looking straight ahead (parallel to the floor).

To weigh an infant, undress the infant, ensure the room is warm, and the weighing machine is calibrated and then record the weight.

To weigh an infant, undress the infant, ensure the room is warm, and the weighing machine is calibrated and then record the weight.

To weigh a child, remove only shoes and stand child on weighing machine.

To weigh a child, remove only shoes and stand child on weighing machine.

Language development (ability to speak and use words)

Infant – cooing, babbling, laughing, gurgling

Infant – cooing, babbling, laughing, gurgling

1 year – can say few words, imitates sounds, recognizes some words

1 year – can say few words, imitates sounds, recognizes some words

2 years – can use 2–3 words in phrases and knows about 200–300 short words, e.g. ‘want my teddy’

2 years – can use 2–3 words in phrases and knows about 200–300 short words, e.g. ‘want my teddy’

3 years – can use 4–5 words in sentences and has a vocabulary of 800–900 words

3 years – can use 4–5 words in sentences and has a vocabulary of 800–900 words

4–5 years – can use complete sentences clearly and has a vocabulary of 1500–2500 words

4–5 years – can use complete sentences clearly and has a vocabulary of 1500–2500 words

Deviations from normal

Pre-schoolers (< 5 years)

Communication delay or disorders may be present with preschoolers who:

Have atypical comprehension of commands or requests

Have atypical comprehension of commands or requests

May have few words or exhibit unintelligible speech

May have few words or exhibit unintelligible speech

May omit many speech sounds or produce unusual combinations of speech sounds

May omit many speech sounds or produce unusual combinations of speech sounds

May grunt or point to items rather than attempt to produce words

May grunt or point to items rather than attempt to produce words

May show disinterest in toys or games suitable for their age group

May show disinterest in toys or games suitable for their age group

May be withdrawn or prefer to play alone if speech disordered

May be withdrawn or prefer to play alone if speech disordered

May display aggression (e.g. tantrums, biting, kicking) because of frustration with communicating needs

May display aggression (e.g. tantrums, biting, kicking) because of frustration with communicating needs

Cognitive development (the ability to reason, think, perceptions, attention, memory)

Problem-solving may be seen in delayed development of basic concepts such as object permanence

Problem-solving may be seen in delayed development of basic concepts such as object permanence

Memory can be demonstrated by inability to remember an event or words that were previously known

Memory can be demonstrated by inability to remember an event or words that were previously known

General learning skills can be seen in reduced ability to acquire new skills, learn simple tasks or to apply skills to new events

General learning skills can be seen in reduced ability to acquire new skills, learn simple tasks or to apply skills to new events

May play and interact with younger children

May play and interact with younger children

May have poor social skills and poor ability to assess social situations (e.g. autism)

May have poor social skills and poor ability to assess social situations (e.g. autism)

May have age-appropriate language skills but display cognitive deficits (e.g. high functioning autism)

May have age-appropriate language skills but display cognitive deficits (e.g. high functioning autism)

May display impulsivity, hyperactivity, and inattention (e.g. attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, ADHD).

May display impulsivity, hyperactivity, and inattention (e.g. attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, ADHD).

Nutritional assessment

History, psychological and social status

Been ill at home or on the ward for a long period of time prior to admission to hospital

Been ill at home or on the ward for a long period of time prior to admission to hospital

Has recently suffered a bad experience (death of close family member, friend)

Has recently suffered a bad experience (death of close family member, friend)

Is the family on income support, one parent family

Is the family on income support, one parent family

The appearance of their skin in terms of colour and condition

The appearance of their skin in terms of colour and condition

Look in the mouth: are the gums swollen, teeth discoloured

Look in the mouth: are the gums swollen, teeth discoloured

Physical examination

Check the oral cavity – is there a sore mouth or lips?

Check the oral cavity – is there a sore mouth or lips?

Check for the presence of difficulty in chewing and swallowing or any physical difficulties with feeding.

Check for the presence of difficulty in chewing and swallowing or any physical difficulties with feeding.

Is there any nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea; this results in reduced absorption and appetite.

Is there any nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea; this results in reduced absorption and appetite.

Any constipation will affect nutritional intake and can lead to a feeling of fullness, discomfort, depression and confusion, thereby reducing food intake.

Any constipation will affect nutritional intake and can lead to a feeling of fullness, discomfort, depression and confusion, thereby reducing food intake.

Simple respiratory function tests can be recorded, such as vital capacity, maximum inspiration and maximum expiration, to determine respiratory muscle strength.

Simple respiratory function tests can be recorded, such as vital capacity, maximum inspiration and maximum expiration, to determine respiratory muscle strength.

Diet history

Likes and dislikes, e.g. fruit and vegetables, meat

Likes and dislikes, e.g. fruit and vegetables, meat

Religion – are there any long periods of fasting in the family – are they vegetarian?

Religion – are there any long periods of fasting in the family – are they vegetarian?

Changes in weight; loss of subcutaneous fat, apathy or lack of energy

Changes in weight; loss of subcutaneous fat, apathy or lack of energy

Type, quantity and texture of food eaten since the onset of illness, as disease often alters appetite

Type, quantity and texture of food eaten since the onset of illness, as disease often alters appetite

Have there been any changes in taste and the ability to obtain food?

Have there been any changes in taste and the ability to obtain food?

Ask to recall food intake over the previous few days

Ask to recall food intake over the previous few days

Consider issues related to the parents/carers:

Consider issues related to the parents/carers:

Anthropometric measurements

A baby or infant should be weighed naked (any additions e.g. splint/medical equipment should be noted in the notes)

A baby or infant should be weighed naked (any additions e.g. splint/medical equipment should be noted in the notes)

Do not leave a baby/infant unattended in the scales

Do not leave a baby/infant unattended in the scales

Always record exact weight, do not round the figures up or down.

Always record exact weight, do not round the figures up or down.

Height can also be used to determine if a child is growing at an optimal rate. Any reduction in growth rate may indicate a pathological disorder requiring possible diagnosis and intervention. The differences between measuring a baby’s/infant’s length and a child height is detailed in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3 Measuring a baby’s/infant’s length and a child’s height

| Baby’s / infant’s length | Child’s height |

|---|---|

| The baby/infant should be lying down perfectly flat on a solid even surface | A child may require some input from a play specialist or nurse prior to the procedure |

| With assistance of another nurse/parent/carer position the baby on the measuring mat | Remove shoes and in some instances socks as well, hair clips |

| Baby/infant’s head should be touching the top of the mat | Position the child with their feet together, flat on the floor, legs straight, back against the wall, arms by their side, their head should be facing forward |

| The body should be in alignment | Put pressure on the child’s mastoids and take the reading of the height after full expiration |

| Record the baby/infant’s length | Record the reading viewed at eye level |

Biochemical measurements

Biochemical measurements can also be used, the most common in use are:

Serum albumin: with a level of less than 35 g/l being indicative of protein-energy malnutrition, it can be inaccurate as conditions such as stress, nephrosis and burns also exhibit hypoalbuminia. This makes the measurement often misleading and not altogether reflective of nutritional deficiency in the short term. In the chronic situation, serum albumin remains a simple and reliable indicator of malnutrition.

Serum transferrin: levels could be considered a better marker of acute nutritional depletion. Interpretation of serum levels is complicated by factors such as iron deficiency, which directly affects transferrin production and so may not be wholly appropriate as a predictor of malnutrition.

Serum haemoglobin: measurements will highlight the presence of anaemia, which has been correlated with pressure sore development. Anaemia can occur for a variety of reasons, but may be directly related to dietary inadequacy and questioning of dietary intake should always follow this up.

Malnutrition

Physiological effects of malnutrition

During the first day of fasting, low glucose levels stimulate glucagon secretion by the pancreas. As a result, glycogen is converted to glucose and released from the liver. This restores blood glucose levels to normal. Glycogen can be lost without any physiological consequences.

During the first day of fasting, low glucose levels stimulate glucagon secretion by the pancreas. As a result, glycogen is converted to glucose and released from the liver. This restores blood glucose levels to normal. Glycogen can be lost without any physiological consequences.

These mechanisms supply blood glucose but cannot sustain blood glucose for a long period of time.

These mechanisms supply blood glucose but cannot sustain blood glucose for a long period of time.

Fat stores may be used for energy. This method requires a major body adjustment, as all other body tissues must reduce their oxidation of glucose and switch over to fat as their energy source.

Fat stores may be used for energy. This method requires a major body adjustment, as all other body tissues must reduce their oxidation of glucose and switch over to fat as their energy source.

As the liver metabolizes fat, ketone bodies are produced in large quantities. These are oxidized by the body into carbon dioxide, water and adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

As the liver metabolizes fat, ketone bodies are produced in large quantities. These are oxidized by the body into carbon dioxide, water and adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

Heal wounds, which increases risk of pressure sore development

Heal wounds, which increases risk of pressure sore development

Manufacture haemoglobin, which reduces the oxygen carrying capacity of the blood

Manufacture haemoglobin, which reduces the oxygen carrying capacity of the blood

Produce white blood cells, causing suppression of the immune response and reducing child’s defence mechanisms

Produce white blood cells, causing suppression of the immune response and reducing child’s defence mechanisms

Maintain adequate respiratory drive due to the reduction in pulmonary diaphragmatic muscle mass and strength, predisposing patient to respiratory failure.

Maintain adequate respiratory drive due to the reduction in pulmonary diaphragmatic muscle mass and strength, predisposing patient to respiratory failure.

Consequences of malnutrition in children

Higher incidence of pneumonia due to impairment in respiratory function.

Higher incidence of pneumonia due to impairment in respiratory function.

Catabolism and weight loss are accelerated

Catabolism and weight loss are accelerated

There is impaired gut integrity.

There is impaired gut integrity.

Delayed wound healing; this can lead to reduced healing of surgical sites.

Delayed wound healing; this can lead to reduced healing of surgical sites.

Have an increased susceptibility to wound or systemic infections.

Have an increased susceptibility to wound or systemic infections.

There are decreased visceral proteins.

There are decreased visceral proteins.

Information should be based on nurses’ observations of the child

Pressure area risk assessment

those who are in a poor state of health and have numerous medical, surgical problems

those who are in a poor state of health and have numerous medical, surgical problems

babies, infants, children who have some degree of immobility, e.g. those nursed in intensive care, neonates, those undergoing prolonged surgery, spinal injury.

babies, infants, children who have some degree of immobility, e.g. those nursed in intensive care, neonates, those undergoing prolonged surgery, spinal injury.

1. Pressure greater than 25 mmHg will occlude capillaries. The tissues are thus deprived of blood, and if the pressure is maintained for a sufficient length of time, the tissues die.

2. Friction is a combination of pressure and friction caused by dragging children up the bed, which seriously damages the micro-circulation.

3. Pressure and strain to structures so great that they tear the muscle and skin fibres from their bony attachments cause shearing forces.

1. Intrinsic factors – aspects of the patients’ condition, mental, physical, and medical states, e.g. malnutrition, age, altered consciousness, immobility.

2. Extrinsic factors – external effects of drugs, treatment regimes, manual handling techniques, personal hygiene, and weight distribution.

1. The Braden Q tool – used for children between the ages of 21 days to 8 years, contains the same six criteria for use with adults, which have been modified to make them developmentally appropriate for children. There is the addition of tissue oxygenation and perfusion:

2. The Glamorgan Scale – developed especially for children and takes into consideration:

Wound assessment

1. A body diagram to record the child’s wound sites and in the case of multiple wounds these should be numbered individually.

2. A separate assessment sheet should determine the site of each wound and/or the number identified from the initial body diagram.

3. Consider the major areas in relation to the condition of any wound (Table 2.4).

4. The maximum dimensions should be traced and recorded, giving the length, width and depth of the wound in centimetres, in order to have a standard method of measurement.

5. Consider the child’s age and weight and take into account current diagnosis and any medications.

Table 2.4 Major areas that should be included in a wound assessment

| Record of wound site | Body diagram from different angles: Back Front Legs Front Back Medial Lateral |

| Condition of wound | Wound dimensions Nature of wound bed Exudate Odour Pain (site, frequency, severity) Wound margin Erythema of surrounding skin Condition of surrounding skin infection |

| Dimensions/drawing | Length Width Depth Outside tracking Health granulating tissue Sloughy areas |

| Documentation | All these points need to be taken into consideration when documenting nursing observations and wound treatments in relation to wound care |

Neurological assessment

Alert responds to vocal stimuli, responds to painful stimuli or unresponsive to all stimuli. Alternatively, use the Glasgow Coma Scale.

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)

The GCS assesses two aspects of consciousness, arousal and cognition:

1. Arousal: involves being aware of the environment:

2. Cognition: demonstrates an understanding of what the observer has said through an ability to perform tasks.

Record consciousness level and the activity of the ANS or mental state.

Record consciousness level and the activity of the ANS or mental state.

assess consciousness with ease and standardize clinical observations of patients with impaired consciousness.

assess consciousness with ease and standardize clinical observations of patients with impaired consciousness.

Monitor the progress of head-injured patients, and children undergoing intracranial surgery.

Monitor the progress of head-injured patients, and children undergoing intracranial surgery.

Monitor any other neurological disorder (cerebral vascular accident, encephalitis, meningitis).

Monitor any other neurological disorder (cerebral vascular accident, encephalitis, meningitis).

Minimize variation and subjectivity in the clinical assessment of children.

Minimize variation and subjectivity in the clinical assessment of children.

Provide a neurological assessment that might indicate the level of patient dependency and subsequent need for nursing interventions.

Provide a neurological assessment that might indicate the level of patient dependency and subsequent need for nursing interventions.

Assess the infant/toddler/child from afar; note their interaction with parents or carers, involve them, discuss your observations and ask them if they are happy with the way the child is behaving. You will need to use your knowledge of normal development landmarks (see Section one). The GCS is based on three aspects of brain function:

1. Eye opening – tests a primitive response managed by the reticular activating system, which extends from the brain stem through the thalamus into the cerebral cortex. Consciousness depends on the interactions between them.

2. Verbal response – tests higher functions of the brain in the cerebral cortex; the most likely stimulus to initiate a response is the sound of the child’s mother’s voice or the sound of their name.

3. Motor response – tests higher functions of the brain in the cerebral cortex; this varies with age.

The rating for eye opening based on a four-point scale (1–4)

Assessing eye opening response in infants:

If the child is not opening their eyes spontaneously, ask the parents to speak to the infant or child by calling his/her name, they may need painful stimuli to initiate a response (see later).

If the child is not opening their eyes spontaneously, ask the parents to speak to the infant or child by calling his/her name, they may need painful stimuli to initiate a response (see later).

If there is no response to speech, attempt to wake him or her up by touch by rubbing or stroking the infant’s limbs.

If there is no response to speech, attempt to wake him or her up by touch by rubbing or stroking the infant’s limbs.

If there is no response to speech or touch use painful stimuli. This will depend on local hospital policy and the age of the infant; the principle is to do no harm. The ear lobe is often used in infants; it is not very painful but may provide enough stimulation to arouse an infant.

If there is no response to speech or touch use painful stimuli. This will depend on local hospital policy and the age of the infant; the principle is to do no harm. The ear lobe is often used in infants; it is not very painful but may provide enough stimulation to arouse an infant.

For best results the stimulus should last between 20–30 seconds.

For best results the stimulus should last between 20–30 seconds.

Assessing eye opening response in a child:

As applied to an infant, involve the parents or carers and check with them if they are happy with the child’s behaviour.

As applied to an infant, involve the parents or carers and check with them if they are happy with the child’s behaviour.

If the child is not opening his/her eyes spontaneously, ask the parent to call the child’s name, if there is no response then attempt to wake them up with touch e.g. rubbing or stroking limbs.

If the child is not opening his/her eyes spontaneously, ask the parent to call the child’s name, if there is no response then attempt to wake them up with touch e.g. rubbing or stroking limbs.

If there is no response to speech or touch use a painful stimulus:

If there is no response to speech or touch use a painful stimulus:

These can all lead to bruising so alternate stimuli points to prevent unnecessary bruising.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree