Drugs Used for Seizure Disorders

Objectives

2 Discuss the basic classification systems used for epilepsy.

3 Cite the desired therapeutic outcomes from antiepileptic agents used for seizure disorders.

6 Cite precautions needed when administering phenytoin or diazepam intravenously.

Key Terms

seizures ( ) (p. 287)

) (p. 287)

epilepsy ( ) (p. 287)

) (p. 287)

generalized seizures ( ) (p. 287)

) (p. 287)

partial seizures ( ) (p. 287, 288)

) (p. 287, 288)

anticonvulsants ( ) (p. 287)

) (p. 287)

antiepileptic drugs ( ) (p. 287)

) (p. 287)

tonic phase ( ) (p. 288)

) (p. 288)

clonic phase ( ) (p. 288)

) (p. 288)

postictal state ( ) (p. 288)

) (p. 288)

status epilepticus ( ) (p. 288)

) (p. 288)

atonic seizure ( ) (p. 288)

) (p. 288)

myoclonic seizures ( ) (p. 288)

) (p. 288)

absence (petit mal) epilepsy ( ) (p. 288)

) (p. 288)

seizure threshold ( ) (p. 289)

) (p. 289)

gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (

) (p. 289)

) (p. 289)

treatment responsive ( ) (p. 289)

) (p. 289)

treatment resistant ( ) (p. 289)

) (p. 289)

gingival hyperplasia ( ) (p. 291)

) (p. 291)

nystagmus ( ) (p. 295)

) (p. 295)

urticaria ( ) (p. 300)

) (p. 300)

Seizure Disorders

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

Seizures are a symptom of an abnormality in the nerve cells of the brain. A seizure is a brief period of abnormal electrical activity in these nerve centers. Seizures may be convulsive (i.e., accompanied by violent, involuntary muscle contractions) or nonconvulsive. During a seizure, there is often a change in the person’s consciousness, sensory and motor systems, subjective well-being, and objective behavior. Seizures may result from fever, head injury, brain tumor, meningitis, hypoglycemia, a drug overdose or withdrawal, or poisoning. It is estimated that 8% to 10% of all people will have a seizure during their lifetimes. If the seizures are chronic and recurrent, the patient is diagnosed as having epilepsy. Epilepsy is the most common of all neurologic disorders. It is not a single disease but rather several different disorders that have one common characteristic: a sudden discharge of excessive electrical energy from nerve cells in the brain. An estimated 2.3 million Americans have these disorders, and approximately 125,000 new cases are diagnosed annually. The cause of epilepsy may be unknown (i.e., idiopathic), or it may be the result of a head injury, a brain tumor, meningitis, or a stroke.

Epilepsy has been classified in several ways. Traditionally, the most important subdivisions have been grand mal, petit mal, psychomotor, and Jacksonian types. These conditions also can be grouped based on type of seizure, cause, location in the brain involved, causal factors, and the patient’s age at onset as well as their severity, frequency, and prognosis. An international commission reclassified epilepsies into two broad categories based on their clinical and electroencephalographic patterns: generalized and partial (localized). Generalized seizures refer to those that affect both hemispheres of the brain, are accompanied by a loss of consciousness, and may be subdivided into convulsive and nonconvulsive types. Partial seizures may be subdivided into simple and complex symptom types; a change in consciousness occurs with complex seizures. Partial seizures begin in a localized area in one hemisphere of the brain. Both simple and complex partial seizures can evolve into generalized seizures, which is a process that is referred to as secondary generalization. Epilepsy is treated almost exclusively with medications known as anticonvulsants or a term gaining more widespread use, antiepileptic drugs.

Descriptions of Seizures

Generalized Convulsive Seizures

The most common generalized convulsive seizures are the tonic-clonic, atonic, and myoclonic seizures.

Tonic-Clonic (Grand Mal) Seizures

Tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizures are the most common type of seizure. During the tonic phase, patients suddenly develop intense muscular contractions that cause them to fall to the ground, lose consciousness, and lie rigid. The back may arch, the arms may flex, the legs may extend, and the teeth may clench. Air is forced up the larynx, extruding saliva as foam and producing an audible sound like a cry. Respirations stop, and the patient may become cyanotic. The tonic phase usually lasts 20 to 60 seconds before diffuse trembling sets in. The clonic phase, which is manifested by bilaterally symmetrical jerks alternating with the relaxation of the extremities, then begins. The clonic phase starts slightly and gradually becomes more violent, and it involves the whole body. Patients often bite their tongues and become incontinent of urine or feces. Usually, within 60 seconds, this phase proceeds to a resting, recovery phase of flaccid paralysis and sleep that lasts 2 to 3 hours (the postictal state). The patient has no recollection of the attack on awakening. The severity, frequency, and duration of attacks are highly variable; they may last from 1 to 30 minutes and occur as frequently as daily or as infrequently as every few years. Status epilepticus is a rapidly recurring generalized seizure that does not allow the individual to regain normal function between seizures. It is a medical emergency that requires prompt treatment to minimize permanent nerve damage and prevent death.

Atonic or Akinetic Seizures

A sudden loss of muscle tone is known as an atonic seizure or a drop attack. This may be described as a head drop, the dropping of a limb, or the slumping of the body to the ground. A sudden loss of muscle tone results in a dramatic fall. Seated patients may slump forward violently. Patients usually remain conscious. The attacks are short, but injury frequently occurs from the uncontrolled falls. These patients often wear protective headgear to minimize trauma.

Myoclonic Seizures

Myoclonic seizures involve lightning-like repetitive contractions of the voluntary muscles of the face, trunk, and extremities. The jerks may be isolated events, or they may be rapidly repetitive. It is not uncommon for patients to lose their balance and fall to the floor. These attacks occur most often at night as the patient enters sleep. There is no loss of consciousness with myoclonic seizures.

Generalized Nonconvulsive Seizures

By far the most common generalized nonconvulsive seizure disorder is absence (petit mal) epilepsy. These seizures occur primarily in children, and they usually disappear at puberty; however, the patient may develop a second type of seizure activity. Attacks consist of paroxysmal episodes of altered consciousness lasting 5 to 20 seconds. There are no prodromal or postictal phases. Patients appear to be staring into space, and they may exhibit a few rhythmic movements of the eyes or head, lip smacking, mumbling, chewing, or swallowing movements. Falling does not occur, patients do not convulse, and they will have no memory of the events that occur during the seizures.

Partial (Localized) Seizures

Classification of partial seizures is subdivided into partial simple motor seizures and partial complex seizures. Partial simple motor (Jacksonian) seizures involve localized convulsions of voluntary muscles. A single body part such as a finger or an extremity may start jerking. Turning the head, smacking the lips, mouth movements, drooling, abnormal numbness, tingling, and crawling sensations are other indications of partial simple motor seizures. The muscle spasm may end spontaneously, or it may spread over the whole body. The patient does not lose consciousness unless the seizure develops into a generalized convulsion. Partial seizures with complex symptoms (psychomotor seizures) are manifested by a vast array of possible symptoms. The patient’s outward appearance may be normal, or there may be aimless wandering, lip smacking, unusual and repeated chewing or swallowing movements. The person is conscious, but may be in a confused, dreamlike state. The attacks, which may occur several times daily and last for several minutes, commonly end during sleep or with a clouded sensorium, and the patient usually has no recollection of the events of the attack.

Anticonvulsant Therapy

Identifying the cause of seizure activity is important for determining the type of therapy required. Contributing factors (e.g., head injury, fever, hypoglycemia, drug overdose) must be specifically treated to correct the underlying cause before chronic anticonvulsant therapy is started. After the underlying cause is treated, it is rare that chronic antiepileptic therapy is needed. When seizure activity continues, drug therapy is the primary form of treatment. The goals of therapy are to improve the patient’s quality of life, reduce the frequency of seizure activity, and minimize the adverse effects of the medication. Therapeutic outcomes must be individualized for each patient. The selection of the medication depends on the type of seizure, the age and gender of the patient, any other medical conditions present, and the potential adverse effects of the individual medications.

Actions

Unfortunately, the mechanisms of seizure activity are extremely complex and not well understood. In general, anticonvulsants increase the seizure threshold and regulate neuronal firing by inhibiting excitatory processes or enhancing inhibitory processes. The medications can also prevent the seizure from spreading to adjacent neurons. Phenytoin, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, zonisamide, and valproic acid act on sodium and calcium channels to stabilize the neuronal membrane and may decrease the release of excitatory neurotransmitters. Barbiturates, benzodiazepines, tiagabine, gabapentin, and pregabalin enhance the inhibitory effect of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), an inhibitory neurotransmitter that counterbalances the effect of excitatory neurotransmitters. Seizure control medications are sometimes subdivided into broad-spectrum and narrow-spectrum agents in relation to their efficacy against different types of seizures. The broad-spectrum agents are levetiracetam, topiramate, valproic acid, zonisamide, and lamotrigine. These drugs are often used for the initial treatment of a patient with a newly diagnosed seizure disorder. The narrow-spectrum agents are phenytoin, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, tiagabine, gabapentin, and pregabalin (French, 2008).

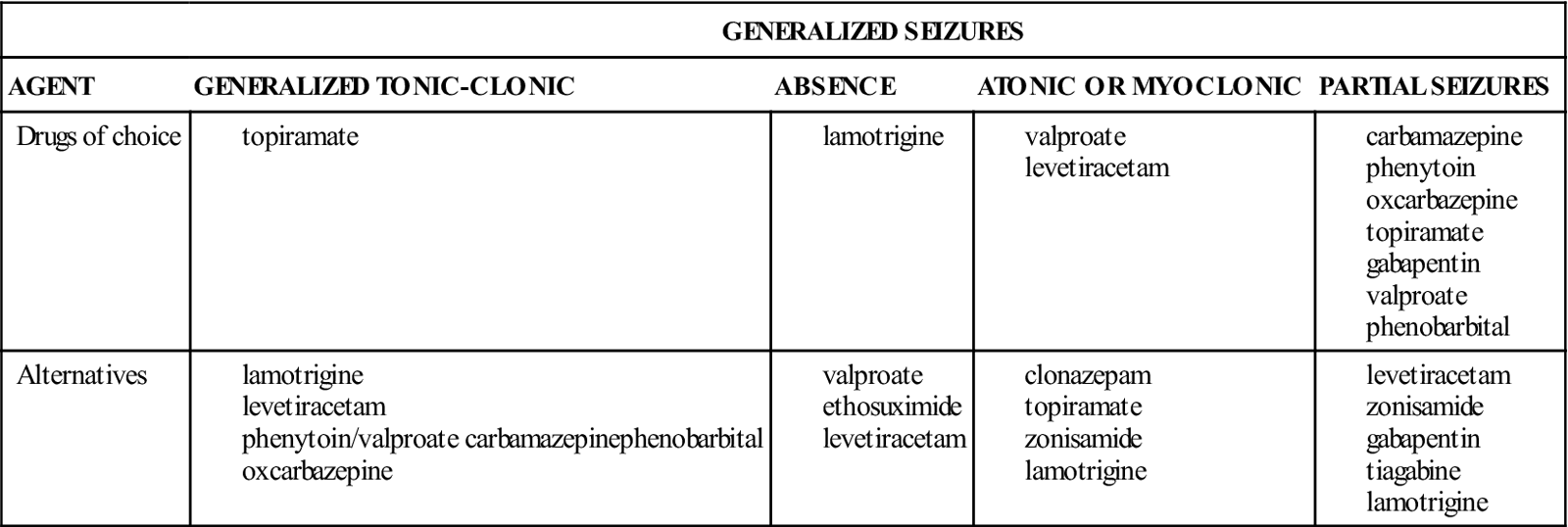

In general, anticonvulsant therapy should start with the use of a single drug selected from a group of first-line agents based on the type of seizure. Table 19-1 lists the antiepileptic drugs of choice for primary seizure disorders. The agents classified as first-line therapy are fairly similar with regard to their potential to prevent seizures, but their adverse effects vary. Thus, the drug chosen is selected first on its ability to control a certain form of epilepsy and then on its adverse effect profile and its likelihood to cause adverse effects in a particular patient. In general, if treatment is not successful with the first agent chosen, that agent is discontinued, and another first-line agent is started. If treatment fails with the second agent, the health care provider may decide to discontinue the second agent and start a third first-line agent, or combination therapy may be started by adding an alternative medication to one of the first-line therapies. Occasionally some patients will require multiple-drug therapy with a combination of agents and will still not be completely free of seizures. Those patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy who respond to treatment are referred to as “treatment responsive,” and those who do not respond to first-line agents are referred to as “treatment resistant.” About half of patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy become free of seizures while using the first prescribed antiepileptic drug. Almost two thirds of patients become free of seizures after receiving the second or third agent.

Table 19-1

Antiepileptic Drugs of Choice Based on Type of Seizure

| GENERALIZED SEIZURES | ||||

| AGENT | GENERALIZED TONIC-CLONIC | ABSENCE | ATONIC OR MYOCLONIC | PARTIAL SEIZURES |

| Drugs of choice | ||||

| Alternatives | ||||

Modified from Rogers SJ, Cavazos JE: Epilepsy. In DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, et al, editors: Pharmacotherapy: A pathophysiologic approach, ed. 8, New York, 2011, McGraw-Hill, p. 985.

Nonpharmacologic treatment of refractory seizures include surgical intervention, the use of an implantable vagus nerve stimulator for children who are 12 years old and older, and a ketogenic diet. The ketogenic diet is used for children, and it includes the restriction of carbohydrate and protein intake; fat is the primary fuel that produces acidosis and ketosis. Although the diet has been shown to reduce refractory seizures in children who have not achieved effective control with drug therapy, the adverse effects of this diet include high blood lipid levels with long-term effects that are not known.

According to a report by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2008), patients who were receiving antiepileptic drugs had approximately twice the risk of suicidal behavior or ideation (0.43%) as compared with patients receiving placebo (0.22%). The increased risk of suicidal behavior and suicidal ideation was observed as early as 1 week after starting the antiepileptic drug, and it continued through 24 weeks of use of the medication. Health care professionals should closely monitor all patients currently receiving antiepileptic drugs for notable changes in behavior that could indicate the emergence or worsening of suicidal thoughts or behavior or depression. The drugs included in the analysis were carbamazepine, felbamate, gabapentin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, pregabalin, tiagabine, topiramate, valproate, and zonisamide.

Uses

Anticonvulsants are used to reduce the frequency of seizures.

Nursing Implications for Anticonvulsant Therapy

Nursing Implications for Anticonvulsant Therapy

Nurses may play an important role in the correct diagnosis of seizure disorders. Accurate seizure diagnosis is crucial to the selection of the most appropriate medications for each patient. Because health care providers are not always able to observe patient seizures directly, nurses should learn to observe and record these events objectively.

Assessment

History of Seizure Activity

• What activities was the patient engaged in immediately before the last seizure?

• Has the patient been ill recently?

• Is there a history of fever, unusual rash, or tick infestation?

• Has the patient noticed any particular activity that usually precedes the attacks?

• When was the last seizure before the current one?

Seizure Description

Postictal Behavior

• Record the level of consciousness (i.e., orientation to time, place, and person).

• Assess the degree of alertness, fatigue, or headache present.

• Evaluate the degree of weakness, any alterations in speech, and memory loss.

• Patients often have muscle soreness and an extreme need for sleep. Record the duration of sleep.

• Evaluate any bodily harm that occurred during the seizure (e.g., bruises, cuts, lacerations).

Implementation

Management of Seizure Activity.

Assist the patient during a seizure by doing the following:

Psychological Implications

Lifestyle.

Encourage the patient to maintain a normal lifestyle. Provide for appropriate limitations (e.g., limits on operating power equipment or motor vehicles; swimming) to ensure patient safety. Make the patient aware of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which was initiated to ensure that individuals with disabilities do not experience discrimination in employment. Contact the Epilepsy Foundation of America and state vocational rehabilitation agencies for information about vocational rehabilitation and employment.

Expressing Feelings.

Allow the patient to ventilate his or her feelings. Seizures may occur in public, and they may be accompanied by incontinence. Patients are usually embarrassed about having a seizure in front of others. Provide for the ventilation of feelings about any discrimination that the patient feels at the workplace. Encourage the open discussion of self-concept issues related to the disease and its impact on daily activities, work, and the responses of others toward the patient.

School-Age Children.

Acceptance by peers can present a problem to a patient in this age-group. The school nurse can help teachers and other children to understand the patient’s seizures.

Denial.

Be alert for signs of denial of the disease, which are indicated by increased seizure activity in a previously well-controlled patient. Question the patient’s adherence with the drug regimen.

Adherence.

Determine the patient’s current medication schedule, including the name of the medication, the dosage, and the time of the last dose. Have any doses been skipped? If so, how many? If adherence appears to be a problem, try to determine the reasons why so that appropriate interventions can be implemented.

Status Epilepticus

Patient Education and Health Promotion

Patient Education and Health Promotion

Exercise and Activity.

Discuss what activities or actions trigger seizures and how to avoid them. Encourage the patient to maintain a regular lifestyle with moderate activity. Avoid excessive exercise that could lead to excessive fatigue.

Nutrition.

Avoid excessive use of stimulants (e.g., caffeine-containing products). Seizures are also known to follow the significant intake of alcoholic beverages; therefore, such ingestion should be avoided or limited. Ask the health care provider whether vitamin supplements are needed, because some anticonvulsants interfere with vitamin and mineral absorption.

Safety.

Teach the patient to avoid operating power equipment or machinery. Driving may be minimized or prohibited. Check state laws regarding how or if an individual with a history of seizure activity may qualify for a driver’s license. Be especially alert to signs of confusion and impaired coordination in older patients. Provide for the patient’s safety.

Stress.

The reduction of tension and stress within the individual’s environment may reduce seizure activity in some patients.

Oral Hygiene.

Encourage daily oral hygiene practices and scheduling of regular dental examinations. Gingival hyperplasia, which is gum overgrowth associated with hydantoins (e.g., phenytoin, ethotoin), can be reduced with good oral hygiene, frequent gum massage, regular brushing, and proper dental care.

Medication Considerations in Pregnancy

Expectations of Therapy.

Discuss the expectations of therapy (e.g., level of seizure control, degree of lethargy, sedation, frequency of use of therapy, relief of symptoms, sexual activity, maintenance of mobility, ability to maintain activities of daily living [ADLs] or work, limits on operating power equipment or motor vehicles). Assess changes in expectations as therapy progresses and as the patient gains understanding and skill with regard to the management of the diagnosis.

Fostering Health Maintenance.

Throughout the course of treatment, discuss medication information and how it will benefit the patient. Recognize that nonadherence may be a means of denial. Explore underlying problems regarding the patient’s acceptance of the disease and the need for strict adherence for maximum seizure control. Provide the patient and significant others with important information contained in the specific drug monograph for the medications prescribed. Additional health teaching and nursing interventions regarding the adverse effects are described in the drug monographs that follow. Seek cooperation and understanding of the following points so that medication adherence is increased: the name of the medication, its dosage, its route and times of administration, and its common and serious adverse effects.

Written Record.

Enlist the patient’s help with developing and maintaining a written record or seizure diary of monitoring parameters (e.g., degree of lethargy; sedation; oral hygiene for gum disorders; degree of seizure relief; any nausea, vomiting, or anorexia present). See the Patient Self-Assessment Form for Anticonvulsants on the Evolve![]() Web site. Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track the patient’s response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient and significant others understand how to use the form. Have others record the date, time, duration, and frequency of any seizure episodes. In addition, record the patient’s behavior immediately before and after seizures. Emphasize taking medications at the same time daily to help maintain a consistent therapeutic drug level. The patient should consult with a pharmacist before taking over-the-counter medications to prevent drug interactions. Have the patient bring the completed form to follow-up visits.

Web site. Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track the patient’s response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient and significant others understand how to use the form. Have others record the date, time, duration, and frequency of any seizure episodes. In addition, record the patient’s behavior immediately before and after seizures. Emphasize taking medications at the same time daily to help maintain a consistent therapeutic drug level. The patient should consult with a pharmacist before taking over-the-counter medications to prevent drug interactions. Have the patient bring the completed form to follow-up visits.

Difficulty With Comprehension.

If it is evident that the patient or family does not understand all aspects of continuing prescribed therapy (e.g., administering and monitoring medications; managing seizure activity, when present; dietary changes; follow-up appointments; the need for lifelong management), consider using social services or visiting nurse agencies.

Drug Therapy for Seizure Disorders

Drug Class: Benzodiazepines

Actions

The mechanism of action for benzodiazepines is not fully understood, but it is thought that benzodiazepines inhibit neurotransmission by enhancing the effects of GABA in the postsynaptic clefts between nerve cells.

Uses

The four benzodiazepines approved for use as anticonvulsants are diazepam, lorazepam, clonazepam, and clorazepate. Clonazepam is useful for the oral treatment of absence, akinetic, and myoclonic seizures in children. Diazepam and lorazepam must be administered intravenously to control seizures; they are the drugs of choice for treating status epilepticus. Clorazepate is used with other antiepileptic agents to control partial seizures. Diazepam administered as a rectal gel may be used to prevent breakthrough seizures.

Therapeutic Outcomes

The primary therapeutic outcomes expected from the benzodiazepines are as follows:

Nursing Implications for Benzodiazepines

Nursing Implications for Benzodiazepines

Premedication Assessment

Availability, Dosage, and Administration

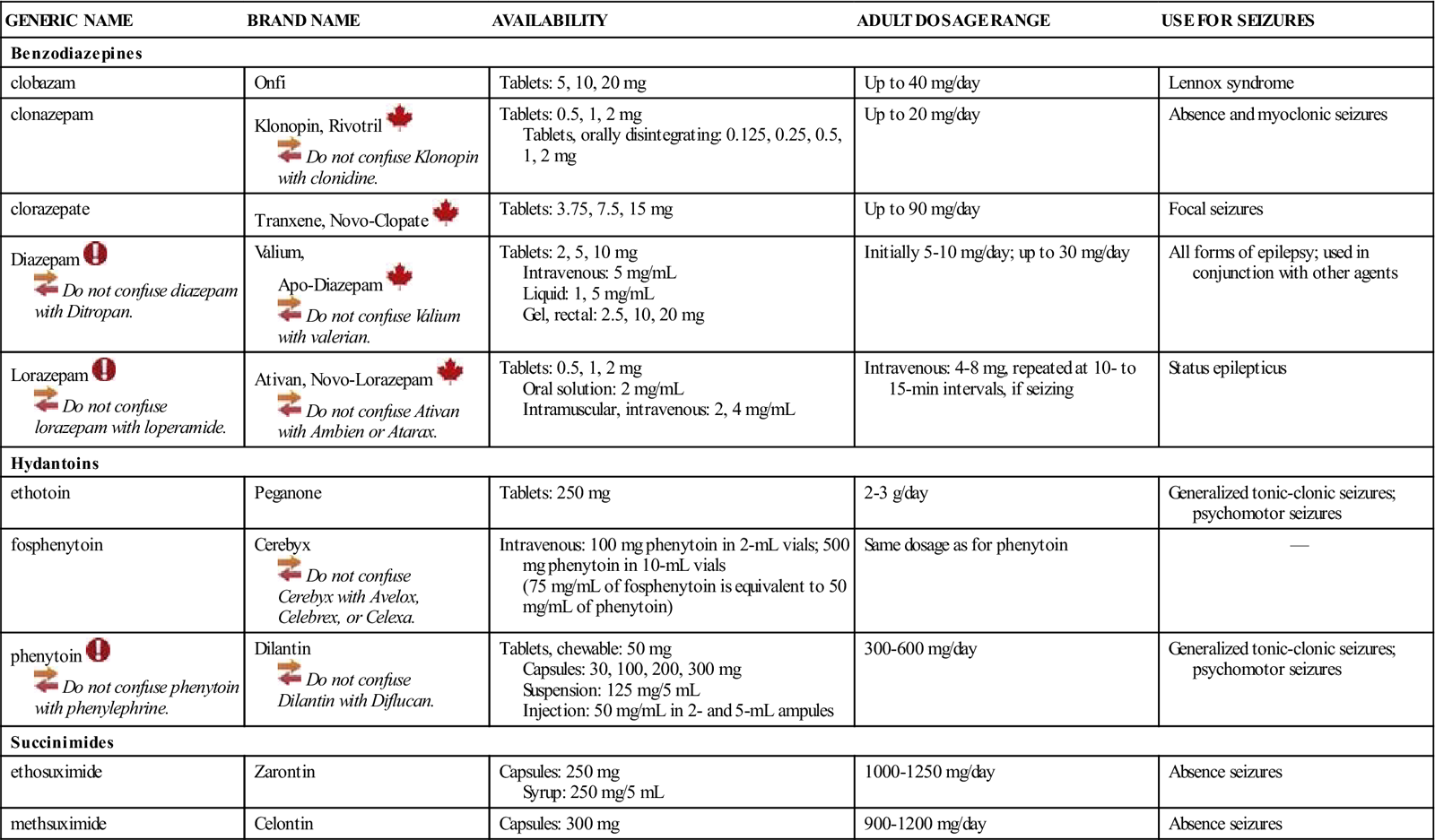

See Table 19-2.

![]() Table 19-2

Table 19-2

| GENERIC NAME | BRAND NAME | AVAILABILITY | ADULT DOSAGE RANGE | USE FOR SEIZURES |

| Benzodiazepines | ||||

| clobazam | Onfi | Tablets: 5, 10, 20 mg | Up to 40 mg/day | Lennox syndrome |

| clonazepam | Klonopin, Rivotril | Tablets: 0.5, 1, 2 mg Tablets, orally disintegrating: 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2 mg | Up to 20 mg/day | Absence and myoclonic seizures |

| clorazepate | Tranxene, Novo-Clopate | Tablets: 3.75, 7.5, 15 mg | Up to 90 mg/day | Focal seizures |

| Diazepam | Valium, Apo-Diazepam | Tablets: 2, 5, 10 mg Intravenous: 5 mg/mL Liquid: 1, 5 mg/mL Gel, rectal: 2.5, 10, 20 mg | Initially 5-10 mg/day; up to 30 mg/day | All forms of epilepsy; used in conjunction with other agents |

| Lorazepam | Ativan, Novo-Lorazepam | Tablets: 0.5, 1, 2 mg Oral solution: 2 mg/mL Intramuscular, intravenous: 2, 4 mg/mL | Intravenous: 4-8 mg, repeated at 10- to 15-min intervals, if seizing | Status epilepticus |

| Hydantoins | ||||

| ethotoin | Peganone | Tablets: 250 mg | 2-3 g/day | Generalized tonic-clonic seizures; psychomotor seizures |

| fosphenytoin | Cerebyx Cerebyx with Avelox, Celebrex, or Celexa. | Intravenous: 100 mg phenytoin in 2-mL vials; 500 mg phenytoin in 10-mL vials (75 mg/mL of fosphenytoin is equivalent to 50 mg/mL of phenytoin) | Same dosage as for phenytoin | — |

| phenytoin | Dilantin Dilantin with Diflucan. | Tablets, chewable: 50 mg Capsules: 30, 100, 200, 300 mg Suspension: 125 mg/5 mL Injection: 50 mg/mL in 2- and 5-mL ampules | 300-600 mg/day | Generalized tonic-clonic seizures; psychomotor seizures |

| Succinimides | ||||

| ethosuximide | Zarontin | Capsules: 250 mg Syrup: 250 mg/5 mL | 1000-1250 mg/day | Absence seizures |

| methsuximide | Celontin | Capsules: 300 mg | 900-1200 mg/day | Absence seizures |

Intravenous Administration.

Do not mix parenteral diazepam or lorazepam in the same syringe with other medications; do not add these to other IV solutions because of precipitate formation. Administer diazepam slowly at a rate of no more than 5 mg per minute or lorazepam at a rate of no more than 2 mg per minute. If at all possible, give these drugs with the patient under electrocardiographic monitoring, and observe closely for bradycardia. Stop boluses until the heart rate returns to normal.

Monitoring

Common Adverse Effects

Neurologic

Sedation, Drowsiness, Dizziness, Fatigue, Lethargy.

The more common adverse effects of benzodiazepines are extensions of their pharmacologic properties. These symptoms tend to disappear with continued therapy and possible dosage readjustment. Encourage the patient not to discontinue therapy without first consulting the health care provider. The patient should be warned not to work with machinery, operate a motor vehicle, administer medication, or perform other duties that require mental alertness. Provide for patient safety during episodes of dizziness and ataxia; report these changes to the health care provider for further evaluation.

Sensory

Blurred Vision.

Caution the patient that blurred vision may occur, and make appropriate suggestions for the patient’s personal safety.

Serious Adverse Effects

Psychological

Behavioral Disturbances.

Behavioral disturbances such as aggressiveness and agitation have been reported, especially in patients who are mentally handicapped or who have psychiatric disturbances. Provide supportive physical care and safety during these responses. Assess the level of the patient’s excitement, and deal calmly with the individual. During periods of excitement, protect the patient from harm, and provide for the physical channeling of energy (e.g., walk with him or her). Seek a change in the medication order.

Hematologic

Blood Dyscrasias.

Routine laboratory studies (i.e., red blood cell count [RBC], white blood cell count [WBC], differential counts) should be scheduled. Monitor the patient for sore throat, fever, purpura, jaundice, or excessive and progressive weakness.

Gastrointestinal

Hepatotoxicity.

The symptoms of hepatotoxicity include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, jaundice, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and abnormal liver function test results (e.g., elevated bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase [AST], alanine aminotransferase [ALT], gamma-glutamyl transferase [GGT], alkaline phosphatase levels; increased prothrombin time [PT]).

Drug Interactions

Drugs That Increase Toxic Effects.

Antihistamines, alcohol, analgesics, anesthetics, tranquilizers, narcotics, cimetidine, sedative-hypnotics, and other anticonvulsants increase the toxic effects of benzodiazepines. Monitor the patient for excessive sedation, and eliminate non-anticonvulsants, if possible.

Smoking.

Cigarette smoking enhances the metabolism of benzodiazepines. Increased dosages may be necessary to maintain effects in patients who smoke.

Drug Class: Hydantoins

Actions

The mechanism of action of the hydantoins is unknown.

Uses

The hydantoins (e.g., phenytoin, ethotoin, fosphenytoin) are anticonvulsants used to control partial (psychomotor) seizures and generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Phenytoin is the most commonly used anticonvulsant of the hydantoins. Fosphenytoin is a prodrug that is converted to phenytoin after administration. Fosphenytoin is particularly useful when loading doses of phenytoin must be administered.

Therapeutic Outcomes

The primary therapeutic outcomes expected from the hydantoins are as follows:

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree