The Pregnant Adolescent and Maternity Nursing in the Community

Objectives

2. Review the phases of adolescent development.

3. Discuss the impact of pregnancy on the development of the adolescent.

4. Examine the influence of pregnancy on adolescent fathers.

5. Discuss the impact of unplanned adolescent pregnancy on achieving the tasks of pregnancy.

6. Explain the risks related to childbearing in adolescents.

7. Outline the health education needs of the adolescent.

8. Recognize two major risks for newborns of adolescent mothers.

9. Name three specific sexually transmitted infections that are increased in the adolescent population.

10. List reasons for the high rate of contraceptive failure in adolescents.

11. List the principles involved in counseling adolescents.

12. Discuss community approaches to pregnancy prevention in adolescents.

14. Describe a prenatal home visit.

15. Outline postpartum teaching that may be provided in the home.

16. Identify two high-risk newborn conditions that may be followed at home.

17. Discuss legal liability and home care.

18. Review the nurse’s role in home care of new mothers and newborns.

19. Review and discuss the Healthy People 2020 objectives related to maternal-infant care.

Key Terms

adolescence (p. 355)

advice telephone lines (p. 365)

hotlines (p. 367)

pelvic inflammatory disease (p. 362)

warm lines (p. 367)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer/maternity

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer/maternity

The Adolescent as Obstetric Patient

Adolescent pregnancy continues to be a social, economic, and health concern in the United States and worldwide. Rates of adolescent pregnancies, abortions, and live births are significantly higher in the United States than in most other developed countries. Clearly, nursing professionals must be aware of all aspects of teen pregnancy. They must be familiar with developmental tasks of adolescents and recognize that teen pregnancy comes at a time when the developmental tasks of adolescents are incomplete. The adolescent is not prepared psychologically or economically for parenthood; thus, both the adolescent (mother or father) and the child are at high risk. This chapter explores the physiologic and psychosocial aspects of pregnancy regarding the adolescent and society, risk factors and outcomes of pregnancy, parenting, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Adolescent Development

Adolescence is the period of transition from childhood to adulthood. It involves change, and adolescents often feel a sense of stress and anxiety throughout this period (Table 18-1). Nurses must understand the types of physical and psychological changes that face the adolescent and the sources of frustration they meet in society. Although specific ages are assigned to young or early adolescents (10 to 13 years), middle adolescents (14 to 16 years), and late adolescents (17 to 20 years), passage of these periods is smooth for some and stormy for others, and some adolescents never complete all aspects of the journey.

Table 18-1

Social Influences of the Community on Adolescent Behavior

| Task Within the Community | Influence | Results |

| Change from elementary school to middle school and high school with new organization of classes. | Changes from core home room classes to independent classes with different teachers are representative of leaving the family concept of elementary school to independent concept of middle school and high school. | The community reinforces the decreasing role of family values and controls and increases self-control and self-responsibility. Selection of classes and friends in this new setting is crucial to positive developmental outcome. |

| Respond to economic pressure and job availability for funds. | Teens need money for fad foods, stylish clothes, and dates and look for sources of income. | In the United States, laws concerning the number of hours young adolescents can work after school keep focus on school; decreased school attendance leads to increased risk behaviors. |

| Teens must develop their own sense of self as it relates to their own sexuality in order to prevent interpreting the public availability of condoms and other barrier control methods of contraception as permission to believe that it is OK to have sex if they use them and that they are safe from unintended pregnancy. | The devices available in public places do not come with detailed instructions on use. Often the teen will be embarrassed to ask questions. | Providing contraceptive devices without appropriate teaching on proper use leads to ineffective birth control, sexually transmitted infections, and unplanned pregnancy. |

The adolescent is confronted by developmental tasks, which vary slightly in different cultures. Tasks and issues that are especially significant during adolescence have been described by many researchers. Major tasks for the adolescent include developing:

Early Adolescence: Ages 10 to 13 Years

Early adolescence is a period of rapid growth and development. The physical changes involve all body systems but especially the cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, and reproductive systems. The adolescent’s self-image is affected as he or she attempts to incorporate both physical and psychological changes. These young adolescents have questions about menstruation, breast development, testicular and penis size, and wet dreams. They wonder whether they are normal and compare themselves with their peers. During early adolescence, exploratory sexual behavior may occur with friends of the same or opposite sex.

During this phase, thinking remains concrete, and the young teenager lacks the capacity for abstract thinking or introspection. The early adolescent has a rich fantasy life. Peer acceptance and conformity are important to the adolescent and may result in parental-adolescent conflict.

Middle Adolescence: Ages 14 to 16 Years

Physiologic growth and development of secondary sexual characteristics may be completed during this period. Middle adolescents focus on making their appearance as attractive as possible. At this time, in an effort to adjust to body changes, adolescents experiment with new images. They use peers to share experiences and try out new roles. Adolescents in this age group have the ability to think more abstractly and may begin to realize the limits of their potential. For those in disadvantaged situations, a feeling of hopelessness may begin. The middle adolescent may become increasingly self-centered and feel invincible. While testing the limits of power, teens may engage in high-risk behaviors. Experiments with drugs, alcohol, and sex are avenues for rebellion. This can be a period of great turmoil for the family as the adolescent struggles for independence and challenges family values and expectations. During this time, adolescents would like to be treated as adults; however, their behavior fluctuates. They may or may not recognize that risk-taking behaviors can bring negative consequences.

Late Adolescence: Ages 17 to 20 Years

Late adolescence is characterized by the ability to maintain stable, reciprocal relationships. The family becomes more important; however, independence from parents is a major part of the developmental task. By late adolescence, many teens have more realistic images of themselves and are more secure about their appearance.

Sexual identity is usually firmly established during late adolescence. Problem solving is used to view consequences of behavior, and plans are more future-oriented. Ideally, the late adolescent will have developed an ability to solve problems, assess many aspects of life situations, and delay immediate gratification. It is important for them to understand the impact of their choices on their future. For example, they need to think through the consequences of not using birth control; recognize that using contraception will prevent pregnancy; and be aware that unprotected sex can lead to illness, which may involve discomfort or be life threatening.

Adolescent Pregnancy

Influences on Sexual Behavior

The meaning of sexuality to adolescents is influenced by communication and visual images. Adolescents’ communication with their parents may be open or limited. Teenagers may avoid conversations about sexuality with their parents because they perceive that their parents send negative messages (admonitions) about sex, resulting in feelings of ambivalence, guilt, and fear for the teen. Some parents live vicariously through their teens and may send messages that actually encourage risk-taking behaviors.

Televisions and computers and the Internet in the home create an environment in which the adolescent can observe sexual activity and form opinions about sexuality. Some adolescents confuse what is portrayed by the media as moral standards or publicly acceptable standards of behavior.

Schools may or may not include sex education in the curriculum. The impact of learning about sexuality in school and from parents, peers, and the media has been studied, and broad well-prepared programs introduced early can have a positive impact. We do know that the outcomes of active sexual behavior are often an unplanned pregnancy and STIs. Health care providers must make use of every opportunity to counsel adolescents about their sexual behavior.

According to comments made by teenagers, risk-taking behaviors with uncertain outcomes are enjoyable, the consequences do not seem that great, and “everybody else is doing it—why shouldn’t I?” Some adolescents are known to brag about their sexual experiences. An adolescent boy may not want to be stigmatized as being the only virgin in his group, and, as a result, sexually inexperienced adolescents conform to their peers. In other words, many adolescent boys and girls become sexually active not because of sexual desire, but because of the need to belong to the group (Table 18-2)

Table 18-2

Psychosocial Tasks that Influence Sexual Activity, Pregnancy, and Parenting in Adolescents

| Psychosocial Task | Influences | Results |

| Develops sense of identity | Influenced by friends, media, and parents, young adolescents are interested in experimenting, whereas older adolescents are interested in commitment. | Dysfunctional, absent, or strict family may increase rebellious response, negative self-image, and risk-taking behaviors. |

| Is egocentric and self-centered | Does not think of others or effect of behavior on newborn or responsibility of parental role. | Self-centered behavior contributes to failed relationships. Adolescent may not respond to needs of newborn, resulting in safety concerns. |

| Seeks independence from family | Values of peers become more important than values of parents; late adolescent selects role models, rejects parents’ rules, and develops own personal values. | Young teens respond to peer pressure; this may influence need to “belong” and influence sexual behavior; scouts, sports, and church groups provide positive role models. |

| Develops emotional intimacy | Develops role models, heroes, close friends of same and, later, opposite sex. | Teen may misinterpret intimacy as sexual relationships and may be disappointed that early sexual relationships are not always related to intimacy or commitment. |

| Develops sexual identity | Accepts puberty and develops relationships. | Sexual abuse and peer pressure can influence early sexual activity and positive sexual identity; early sexual activity is correlated with poor school performance at all socioeconomic levels. |

| Develops sense of career and future | Choice of future depends on exposure and opportunities available. | Use of contraceptives is higher in adolescents with career goals. |

| Develops sense of morality | Operational thought begins in middle adolescence, and personal code of ethics emerges. | Knowledge does not consistently control behavior. Proper role models are helpful guides to adolescents. |

Prevention of Adolescent Pregnancy

In 1996, the U.S. Congress authorized Title V, Section 110 of the Social Security Act, providing funding to administer abstinence-only sex education in school programs and omitting content related to contraception, abortion, and safer sex. Sex education in the schools remains a controversial topic, and there is little agreement about specific content to be taught. Some schools teach abstinence-only programs, and some teach abstinence along with safe sex practices and STI prevention. In one study, abstinence-only programs did not delay intercourse, improve birth control, or decrease pregnancy rates (Oski, 2010). The effective prevention of teen pregnancies and STIs may need to involve theory-based education as well as behavior control (Jenmott, Jenmott, & Fong, 2010). The U.S. teen pregnancy rate for 15 to 17 year olds fell from 77.1 per 1000 in 1990 to 44.4 per 1000 in 2002. Sixty percent of adolescents today are using some form of contraceptive compared to 46% in 1991, and nearly half of the 15 to 19 year olds in the United States report having at least one sexual experience. Eighty percent of teen pregnancies are unplanned, and, although this is a decline since the 1980s and 1990s, it still indicates a need for teen education and counseling (Oski, 2010).

The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy is an organization that has a goal of reducing the rate of teen pregnancy by one third between 2006 and 2015. Teen pregnancy in the United States cost taxpayers $9.1 billion in 2004, with a $1 billion cost in Texas alone and a $12 million cost in Vermont. This organization distributes user-friendly educational materials for practitioners, policy makers, and advocates. Parents may not realize the impact they have in preventing teen pregnancy over their child’s teen peers. The organization also distributes a curriculum-based pamphlet for educational programs and offers tips for parents in how to intervene and prevent teen pregnancy.

The overwhelming consensus is that adolescent pregnancy is a serious problem. As the adolescent matures, parents have less influence on behavior, and peers have more. Peer pressure controls many behaviors. The desire to please peers, the feeling of invincibility, and the belief that the “everyone is looking at me” contribute to participation in high-risk behaviors. The occurrence of sexual abuse and date rape contribute to pregnancy in the adolescent (Box 18-1). Pregnancy prevention programs in schools and the media should assist teens in focusing on their future education and career goals and provide information concerning birth control and STI prevention.

Confidentiality and the Adolescent

Confidentiality laws differ in various states, meaning that some adolescents may not have access to confidential counseling and contraceptive advice. If the health care worker cannot ensure confidentiality, some teens will not seek health care. Adolescents are at greater risk for complications than adults because they are the least likely to seek early health care.

All 50 states have enacted legislation that entitles adolescents to consent to treatment with confidentiality for “medically emancipated conditions.” Although the law varies from state to state (see Online Resources), the list of medically emancipated conditions generally refers to contraception, pregnancy, pregnancy-related care, STIs, substance abuse, and sexual assault. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) ensures patient privacy in all adult cases. All 50 states allow confidential STI testing of adolescents.

Pregnancy and the Adolescent

Menstruation is a sign of a girl’s transition into womanhood and fertility and is celebrated in many cultures. However, in the United States, it is often viewed as a nuisance, stressful, and sometimes uncomfortable. Many young women opt to take medications to reduce the number of menstrual periods from the natural 12 times a year to 1 or 3 times a year. This may prevent unplanned pregnancies but these methods do not protect against STI infection.

Because teens may not receive accurate information elsewhere, parents must be open to discussing sexuality with their adolescent children, and the community must have input to educational programs through organizations such as the parent-teacher associations (PTAs). Providing education and accessible care can have a positive impact on preventing adolescent pregnancy and helping teens understand their own emotional and physical feelings. Nurses can use creative ways to incorporate sexuality information into regular clinic visits. Sexuality should be discussed in the context of relationship issues, rather than dos and don’ts of safe practice. The American Cancer Society recommends that regular Pap smears should begin about 3 years after sexual activity, and the test should be integrated into the health education plan. The impact of pregnancy on the adolescent is discussed in Table 18-3.

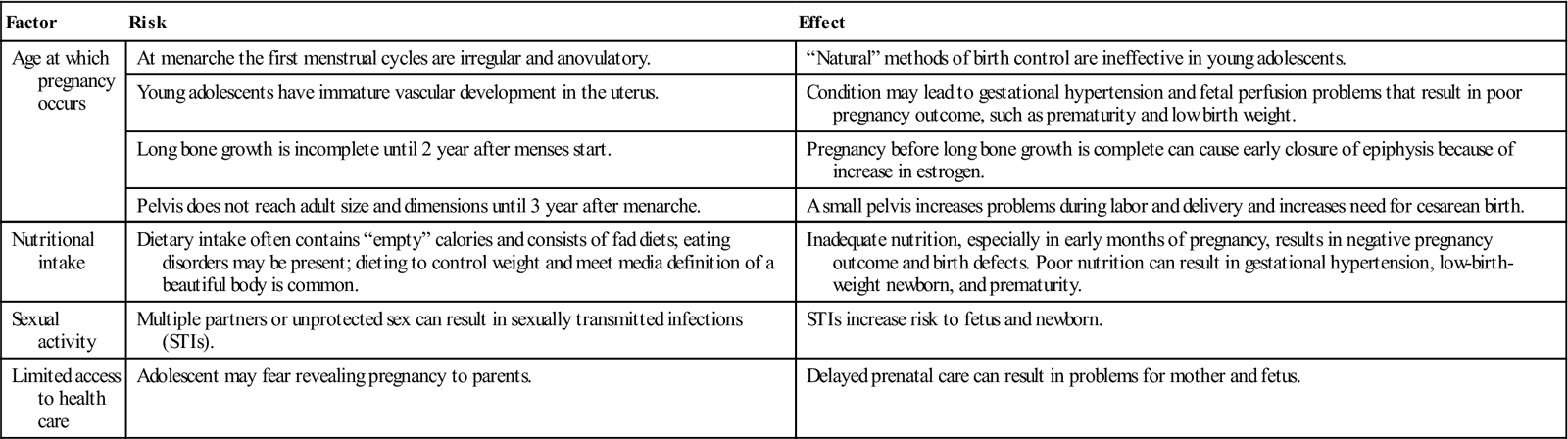

Table 18-3

Developmental and Physiologic Impact of Pregnancy on the Adolescent

| Factor | Risk | Effect |

| Age at which pregnancy occurs | At menarche the first menstrual cycles are irregular and anovulatory. | “Natural” methods of birth control are ineffective in young adolescents. |

| Young adolescents have immature vascular development in the uterus. | Condition may lead to gestational hypertension and fetal perfusion problems that result in poor pregnancy outcome, such as prematurity and low birth weight. | |

| Long bone growth is incomplete until 2 year after menses start. | Pregnancy before long bone growth is complete can cause early closure of epiphysis because of increase in estrogen. | |

| Pelvis does not reach adult size and dimensions until 3 year after menarche. | A small pelvis increases problems during labor and delivery and increases need for cesarean birth. | |

| Nutritional intake | Dietary intake often contains “empty” calories and consists of fad diets; eating disorders may be present; dieting to control weight and meet media definition of a beautiful body is common. | Inadequate nutrition, especially in early months of pregnancy, results in negative pregnancy outcome and birth defects. Poor nutrition can result in gestational hypertension, low-birth-weight newborn, and prematurity. |

| Sexual activity | Multiple partners or unprotected sex can result in sexually transmitted infections (STIs). | STIs increase risk to fetus and newborn. |

| Limited access to health care | Adolescent may fear revealing pregnancy to parents. | Delayed prenatal care can result in problems for mother and fetus. |

Termination of Education

Teenage pregnancy remains the main cause of dropping out of school for adolescent girls. Sexual activity is often associated with poor school performance. The level of formal education is an important predictor of job advancement and earning potential. Adolescent girls who have not completed high school are more likely to be unemployed or employed in entry-level jobs, and lack job security. Generally, in addition to holding low-paying jobs, they may have no health care benefits for themselves and their children.

Adolescent Fathers

It is estimated that 1 in 15 boys fathers a child while he is a teenager. In general, the adolescent father faces sociologic and psychological risks. Many adolescent couples do not plan to marry; however, if the adolescent boy is from a rural area or a specific cultural group, marriage is more likely. Some adolescent fathers, even without marriage, may be involved in the adolescent girl’s pregnancy and child rearing.

Adolescent fathers tend to achieve less formal education than older fathers, and they enter the labor force earlier and with less education. The stresses of pregnancy on the male adolescent come from several sources. He is likely to face a negative reaction from his own family and from the girl’s family. The young girl’s parents may refuse to let him see their daughter, which often makes him feel isolated, alone, and unable to give her support. His future career may be threatened by early marriage or quitting school to support the pregnant girl and new child. Also, his relationship with his peers is altered.

The lack of responsibility shown by some adolescent fathers is a reflection of cultural and community attitudes. Sometimes an adolescent’s ability to impregnate may be viewed, among peers, with a sense of pride and as a sign of manhood.

As part of counseling, the nurse should assess the young man’s stressors, his support system, and his plans for involvement in the pregnancy. If the father is involved in the pregnancy, the young mother may feel less alone and may be better able to discuss her future plans. The young father should be welcomed in the prenatal sessions.

A sizable number of fathers are 6 or more years older than the adolescent mother. Some younger girls are more likely to have much older sexual partners. Older sex partners may be supportive of the pregnant adolescent before the delivery, but their relationship with the mother and newborn may weaken over time. Before delivery, many unwed fathers may plan to contribute to the support of the mother and newborn, but during delivery, most adolescent girls select their mothers as their support person.

Nursing Care of the Pregnant Adolescent

Antepartum Care of Adolescents

During the first prenatal visit, the teen should be welcomed and praised for seeking prenatal care. Knowledge of the adolescent’s individual needs, cultural preferences, and developmental level is essential in planning effective prenatal care and education (Table 18-4). Teaching techniques most effective for adolescents include orienting care protocols to current needs and using visual aids and simple language. Immature communication skills may prevent the teen from expressing herself and asking questions about the pregnancy. Pregnant adolescents should be screened for STIs and substance abuse and offered detailed, mutually developed nutritional plans. Eating foods rich in calcium and vitamin D, regular exercise and muscle activity is necessary for bone health in the adolescent as well as fetal development during pregnancy. A support person who accompanies the adolescent to the clinic should be actively involved in the prenatal education. Community resources and agencies for additional information and counseling should be provided.

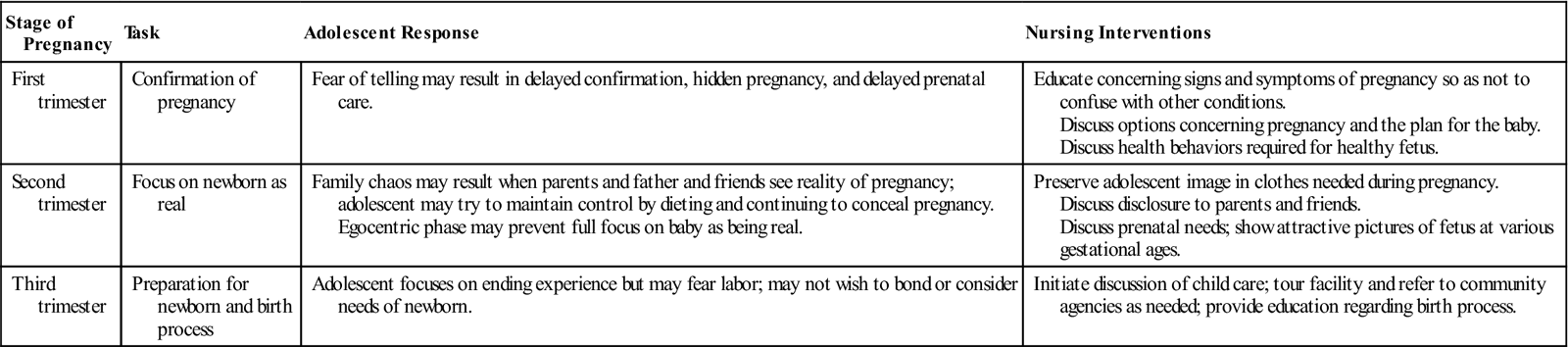

Table 18-4

Nursing Care and the Effect of Adolescence on the Tasks of an Unplanned Pregnancy

| Stage of Pregnancy | Task | Adolescent Response | Nursing Interventions |

| First trimester | Confirmation of pregnancy | Fear of telling may result in delayed confirmation, hidden pregnancy, and delayed prenatal care. | Educate concerning signs and symptoms of pregnancy so as not to confuse with other conditions. Discuss options concerning pregnancy and the plan for the baby. Discuss health behaviors required for healthy fetus. |

| Second trimester | Focus on newborn as real | Family chaos may result when parents and father and friends see reality of pregnancy; adolescent may try to maintain control by dieting and continuing to conceal pregnancy. Egocentric phase may prevent full focus on baby as being real. | Preserve adolescent image in clothes needed during pregnancy. Discuss disclosure to parents and friends. Discuss prenatal needs; show attractive pictures of fetus at various gestational ages. |

| Third trimester | Preparation for newborn and birth process | Adolescent focuses on ending experience but may fear labor; may not wish to bond or consider needs of newborn. | Initiate discussion of child care; tour facility and refer to community agencies as needed; provide education regarding birth process. |

Care of the Adolescent During Labor and Delivery

The adolescent is often modest and may not tolerate pain well. Breathing and relaxation and concentration techniques require patience that many teens lack. Pain control and adequate coaching are essential, especially if a support person is not present. Suggestions to an adolescent support person must be given in a clear, concrete, detailed manner and involve specific directions and activities. The nurse must carefully explain to the adolescent in labor what is being done and what can be expected in order to prevent fear from developing and establish a trusting patient-nurse relationship.

Care of the Postpartum Adolescent

The adolescent may have inadequate coping skills to manage the transition to parenthood and parenting responsibilities. She may feel overwhelmed. Issues of child care, finances, schooling, and family dynamics need to be addressed. Encouragement, support, instruction, and an opportunity to practice perineal self-care and care of the newborn should be provided. The nurse can help adolescent parents integrate the newborn into their lives and offer them resources in the community for follow-up care. Grandparents who take over the complete care of the newborn may interfere with the teen’s development of parent-newborn attachment and adversely affect the teen’s self-image and future parenting skills. Grandparents can be encouraged to help with household tasks and offer positive suggestions and guidance that enable the teen parent to develop coping and parenting skills.

Adolescent Parenting

The transition to parenthood is not easy for adolescents. Often they still have unmet needs in their own phase of development. Acceptance of the role of parenting, including the responsibility of newborn care and their changed self-image, now sets them apart from their peers. Often they feel excluded from desirable “fun” activities characteristic of others their age because they are prematurely forced into the adult role.

Parenting programs available for adolescent mothers may be limited or nonexistent in the community. Adolescent mothers may also find they have little social and financial support. Many adolescent girls welcome the assistance of newborn care offered by their mothers, aunts, or grandmothers. In some cultures, a designated member of the family may accept the complete responsibility of rearing the child.

Many adolescent mothers tend to have repeated pregnancies that are closely spaced, which increases the risks to their health, continued education, and economic future. These factors create family instability and further impair good parenting. If the couple marries as teenagers, divorce tends to be more common.

Characteristic adolescent mother child-rearing practices have been identified, including insensitivity to newborn behavioral cues (e.g., crying, soiling diaper), pattern of limited nonverbal interaction, lack of knowledge of child development, preference for aggressive behavior and physical punishment, and limited learning in their home environment. Adolescent mothers tend to be at risk for non-nurturing behaviors, particularly in areas of inappropriate expectations. They may expect too much of their children because of limited knowledge of child developmental tasks. Adolescents often characterize their newborns as being “fussy.” This description may relate to lack of knowledge that newborn crying is expected behavior. These findings suggest a need for parenting classes for high school students.

Nurses must understand that the adolescent faces many hardships of living in two worlds—adolescence and motherhood. Appointment schedules need to be flexible, or follow-up care may not be sought. Support groups and child care resources may be needed so the adolescent can finish school and participate in some adolescent-type activities. Referral to agencies or professionals to help the adolescent develop coping skills and adapt to the parenting role may be necessary to develop a plan for a more positive future.

Urinary Tract Infections and Sexually Transmitted Infections in Adolescents

Urinary Tract Infections

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) in sexually active young women must be differentiated from STIs. Periurethral bacteria ascend into the bladder, especially after sexual intercourse. Spermicidal coated condoms can alter vaginal flora allowing colonization of bacteria that increases the risk for UTIs. Voiding after sexual intercourse is encouraged. Signs and symptoms of UTIs include:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree