IDENTIFYING THE PROBLEM

In Australia, responsibility for the mental health system is shared between the Commonwealth, or Australian government, state and territory governments and the private sector. Through the Australian Health Care Agreements (AHCA), the Australian government contributes to the public health system overseen by state and territory jurisdictions. State funding provides for inpatient and community services in the public sector, providing approximately two-thirds of funding for mental health services overall. The Australian government contributes funds to the private non-inpatient services and private health insurance. Importantly, the introduction of the Medibank national health insurance scheme in 1974, superseded by Medicare in 1984, provided major reform in healthcare funding and facilitated change in mental health policy. In particular, inclusion of a schedule of rebates for specialist psychiatric consultation meant that no longer was virtually all specialist mental healthcare provided by the state system. The Australian government also funds services provided by primary care practitioners (general practitioners [GPs]) through the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) and mental health pharmaceuticals through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) (see also Ch 4).

Both state and Australian government policy and funding decisions enabled the move from institutional-based to community-based care (‘deinstitutionalisation’) during the 1970s and 1980s. Underlying this move was the progressive ‘mainstreaming’ of mental health services, or the shift from stand-alone services to mental health being provided within the umbrella of general health services. These changes were accompanied by a significant reduction in the number of long-stay beds.

Initially adopted with enthusiasm, as time progressed problems and limitations of community-based care became evident. Symptoms that had been attributed to the institutional environment, such as withdrawal, self-neglect, self-harm and dangerous behaviour, were recognised as inherent to some illnesses and thus requiring ongoing attention irrespective of whether care was provided in an institution or in the community (Gruenberg 1969). In addition, it became clear that while social isolation, institutionalisation, neglect and ill treatment were seen in many asylums, they also occurred in hostels, halfway houses and other housing used by the mentally ill treated in the community (Finlay-Jones 1983). The needs of patients receiving care in the community for a range of non-health services, such as accommodation, vocational training, and recreational, social and disability supports, were often inadequate. Public concern about the care and treatment of the mentally ill, several well-publicised inquiries into psychiatric practices in specific hospitals in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and the Burdekin Report on the Human Rights of the Mentally Ill (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission 1993) set the scene for major reform.

THE POLICY RESPONSES

In 1992, the Australian government, state and territory governments demonstrated increased commitment to mental healthcare and service delivery with the development of a National Mental Health (NMH) Strategy. This comprised three seminal documents: the National Statement of Rights and Responsibilities, the National Mental Health Policy and the first National Mental Health Plan (Australian Health Ministers’ Conference 1992). These set out to articulate the broad objectives and principles that would underpin service development and related legislative frameworks. All state and territory health ministers endorsed these documents.

The aims of the National Mental Health Policy are:

- to promote the mental health of the Australian community and, where possible, prevent the development of mental health problems and mental disorders

- to reduce the impact of mental disorders on individuals, families and the community

- to assure the rights of people with mental disorders.

- to reduce the impact of mental disorders on individuals, families and the community

Specifically, the key elements of the policy are:

- to enhance consumer rights and involvement in mental health services

- to mainstream mental health services into the general health sector

- to integrate inpatient and community mental health services

- to continue to downsize psychiatric hospitals and expand community mental health services

- to link mental health services with other social and disability services needed by people with mental illness

- to enhance the promotion of mental health and the prevention of mental disorders

- to increase support for carers and non-government organisations (NGOs).

- to mainstream mental health services into the general health sector

Additional objectives address workforce and service standards and include: to enhance the role of primary healthcare service providers, especially GPs, in providing mental healthcare; to improve the training and skills of mental health professionals and to address the maldistribution of the mental health workforce; to adopt nationally consistent mental health legislation and service standards; and to encourage mental health research and evaluation.

It should be noted that despite a push towards model mental health legislation that would be consistent across all jurisdictions, the complexity of mental health service provision, and its interaction with other state/territory-based legislative frameworks, has meant that all states and territories have their own mental health legislation. The policy underpinning state/territory-based legislation has been congruent with the national approach – emphasising care in the community where clinically appropriate, with attention to patient rights and external review. There remains variability in the timing of external review and the mechanisms involved, but the principles across the states and territories are consistent. The capacity to provide treatment in the community under involuntary treatment orders is also present in state-based legislation. Unlike New Zealand, and more recently Canada, Australia has not to date set up a national Mental Health Commission to oversee and monitor the implementation of the NMH Strategy.

The National Mental Health Plans

Since 1992, there have been three National Mental Health Plans. These have been agreed to by governments on both sides of the political arena, and have provided a national framework for the Australian government and the state and territory governments to implement mental health reform as defined in the National Mental Health Policy. Progress towards implementation of the policy has been documented through the annual National Mental Health Reports.

The first National Mental Health Plan (1992–1997) (Australian Health Ministers 1992) addressed a range of issues fundamental to the planning and delivery of mental health services in Australia. Specifically, it focused on the following areas: structural and system reform; standards; consumer rights; resource priorities; legislation; and data.

Structural reform involved activity in three key areas: an increase in community-based mental health services; ‘mainstreaming’ of mental health services into the general health sector; and a reduction in the size of stand-alone psychiatric hospitals. While all states and territories worked towards these goals, the degree of change and progress towards these goals was not uniform (Whiteford 1995).

State and territory funding for NGOs providing services for people with mental illness and psychiatric disability was increased. In addition, the NMH Strategy ensured that people with psychiatric disability had access to Australian government disability programs, including Australian government-funded employment services, which they had previously been denied (National Health Strategy 1993).

The Second National Mental Health Plan (1998–2003) (Australian Health Ministers 1998) was released after the results of the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing became available (Australian Bureau of Statistics 1998). This large epidemiological study found that while almost one in five Australians met the criteria for one or more mental disorders during the 12 months before the survey, only 38% of people with a mental disorder used any type of conventional health service during this period. Informed by this study, the Second National Mental Health Plan (the Second Plan) acknowledged that some services had adopted an overly narrow interpretation of the original policy’s priority for people with serious mental illness, leaving many consumers without access to services. Thus, the plan included initiatives to address the clearly identified high level of unmet need.

As a consequence of the above, the Second Plan built on the first plan, but had a broader focus, with an emphasis on promotion of mental health and prevention and early intervention in mental disorders. This included the development of a Mental Health Promotion and Prevention Action Plan, which outlined a 5-year strategic framework and plan to meet the prevention and promotion priorities and outcomes in the Second Plan. The Second Plan also continued structural reform of mental health services with further expansion of community services and ‘mainstreaming’ of acute inpatient services into general hospitals.

In addition, the plan focused on developing partnerships in service reform and delivery. Informed by the work of the Joint Consultative Committee of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (1997) the plan also sought to achieve better integration between care provided by mental health professionals and primary care providers. Under the Second Plan, trials to integrate better public and private mental health sector services were undertaken with the aim of improving quality, appropriateness and efficiency of mental health service delivery (Eager et al. 2005).

The plan also promoted further developments in quality and effectiveness of care. Plans for the measurement and routine collection of consumer outcome measures in mental health services were introduced (Stedman et al. 1998), the National Standards for Mental Health Services (Department of Health and Family Services 1997) were incorporated into the Evaluation and Quality Improvement Program (EQuIP) Standards developed by the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (1996), and the National Standards for the Mental Health Workforce (Department of Health and Ageing 2002) were released. The plan explicitly stated that the focus of services should be expanded to improve treatment and care for a broader range of people with high-level needs, but emphasised the need to continue service reforms for existing clients. The particular needs of Indigenous people, people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds and those living in rural and remote areas were highlighted. In addition, a National Action Plan for Depression (Department of Health and Aged Care [DHAC] 2000) aimed to reduce both the prevalence and impact of depression. Target areas were defined to improve the level of mental health literacy about depression in the general community; to enhance the role of GPs through training, funding and support; and to ensure the workforce in Australian mental health services was used optimally.

The Second Plan was subjected to external review mid-way (Thornicroft & Betts 2001) by international experts. They concluded that the aims of the strategy and plans were admirable, and that Australia was well advanced in mental health policy and reform. They highlighted that progress had been uneven, and that many problems in access, and quality of service remained. The Second Plan, and mental health service delivery more generally, was also subjected to critical consideration by the Mental Health Council of Australia, a government-funded peak lobby group, which carried out extensive consultation through survey and community meetings. The conclusions of the council were far more critical, and were published in a report titled Out of Hospital; Out of Mind! (Groom et al. 2003).

The National Mental Health Plan (2003–2008) (Australian Health Ministers 2003) continued to build on the priorities of the previous two plans but expanded the focus of interest by adopting a population health framework. It included four priority themes: promoting mental health and preventing mental health problems and mental illness; increasing service responsiveness; strengthening quality; and fostering research, innovation and sustainability. The plan emphasised a whole-of-government approach and sought to improve Australia’s mental health through linkages with other areas of public policy, including housing, employment, justice, welfare and education. It continued to promote the rights of consumers and their families and carers, and emphasised the importance of a recovery orientation to service delivery. With its aim of achieving gains through a population health framework the plan considerably broadened the agenda, seeking to improve the treatment, care and quality of life for people with mental health problems as well as those with mental illness across the lifespan.

Changes under the National Mental Health (NMH) Strategy

State-funded mental health services

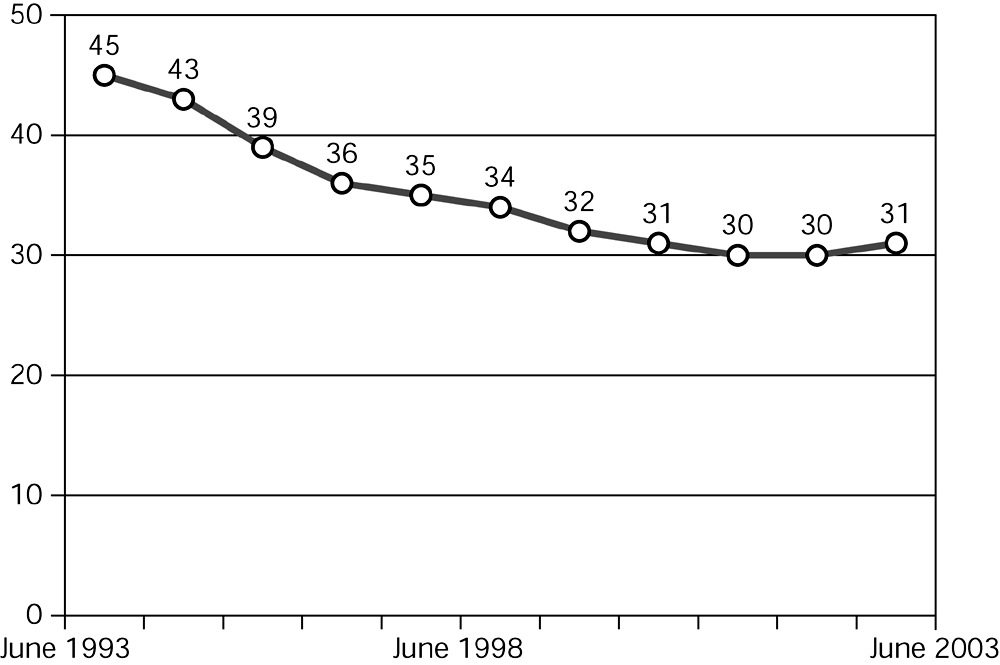

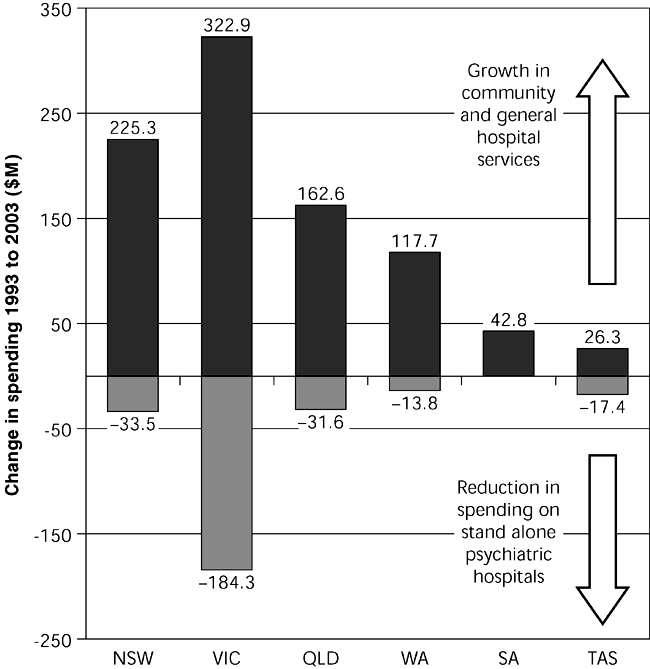

Under the NMH Strategy, there has been a significant reduction in the size and number of stand-alone psychiatric hospitals. They have been replaced by acute beds in general hospitals and a range of community-based services. In 1992–93, 71% of funds were allocated to hospitals and 29% to community-based services. By contrast, in 2002–03, 49% of funds were allocated to hospitals and 51% to community-based services (Department of Health and Ageing 2005; see Figs 18.1 & 18.2). The scale and pace of change has not been uniform across the states and territories. Victoria has implemented the most extensive structural changes. By contrast, in 2003 South Australia had not yet decreased its spending on stand-alone psychiatric hospitals relative to 1993 (Fig 18.2).

Figure 18.1 Total public sector inpatient beds per 100,000, June 1993 to June 2003 Source: Department of Health and Ageing 2005, Fig 22, copyright Commonwealth of Australia, reproduced by permission

Figure 18.2 Have savings from the reduction of state governments stand-alone psychiatric hospitals been transferred to alternative services? Source: Department of Health and Ageing 2005, Fig 17, copyright Commonwealth of Australia, reproduced by permission

Community-based services comprise three broad types of service: ambulatory care clinical services, specialised clinical residential services, and services provided by not-for-profit NGOs to provide support services for people with a psychiatric disability arising from a mental illness. In 1992–93, 23%, 4.4% and 2% of expenditure on mental health services was allocated to ambulatory, residential and NGO services respectively. In 2002–03 this had changed to 38.6%, 7.3% and 5.2%. (Department of Health and Ageing 2005). These figures disguise the significant variability across the states and territories. For example, in 2003 the percentage of total mental health service expenditure allocated to NGOs was 11.5% in Victoria, 11.4% in ACT, and least in South Australia (2.1%) and New South Wales (2.4%). Overall, although community treatment and support services have been strengthened, formal evaluation of progress has acknowledged that community treatment options are still inadequate (DHAC 2000).

Private sector and primary care services

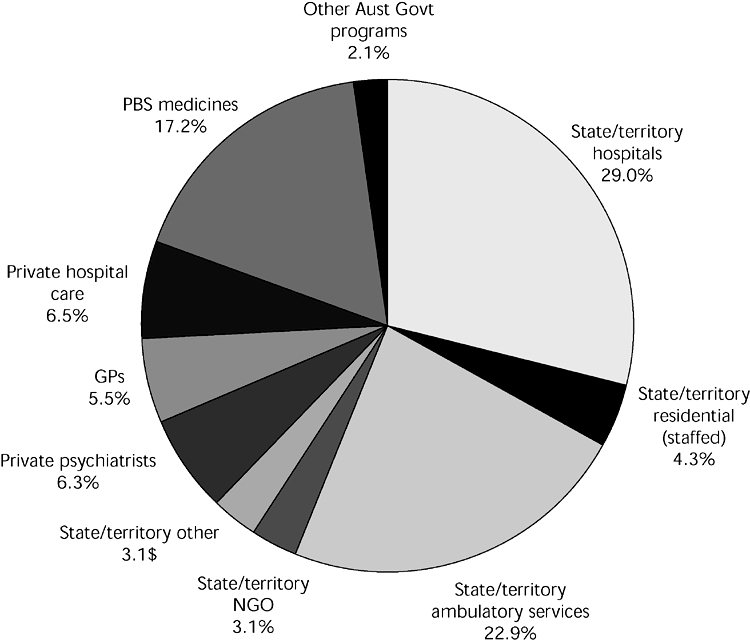

The importance of the private sector in the delivery of mental health services has been increasingly recognised. By 2002–03, the private sector provided 22% of total psychiatric beds and approximately 1.4% of Australians saw a private psychiatrist at least once a year (Department of Health and Ageing 2005; see Figs 18.3 & 18.4). However, there continues to be a significant maldistribution of private psychiatric services. Victoria and South Australia had the highest level of private psychiatrist services in 2002–03, with MBS benefits per capita 34% above the national average. By contrast, in the Northern Territory, Western Australia, Tasmania and the ACT, access to private consultant psychiatrist services is substantially lower than the larger states. Within individual states and territories, consultant psychiatrists are concentrated in capital cities and the majority of people attending for treatment come from metropolitan populations.

Figure 18.3 National spending on mental health, 2002–03 Source: Department of Health and Ageing 2005, Fig 4, copyright Commonwealth of Australia, reproduced by permission

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree