CHAPTER 18. Intrafamilial Homicide and Unexplained Childhood Deaths

Stacey A. Mitchell

The death of a child is tragic whether it results from a natural disease process or from inflicted trauma. Although healthcare providers and law enforcement are exposed almost daily to childhood death, the death of a child seems to take more of a toll when it is due to child maltreatment. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that in 2006, more than 1500 children died from abuse and neglect. That is a rate of 2 per 100,000 children. Approximately 78%, occurred among children younger than four years old (CDC, 2008b). Between ages 4 to 7 years old, 12% died from abuse and neglect (CDC, 2008b). The National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) defines child fatality as the death of a child caused by an injury resulting from some form of abuse and neglect or in a situation where abuse and neglect was a factor (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2009). Most statistics are reported through state welfare agencies. However, information may also be obtained from state child fatality review teams and state health departments. Nonetheless, many researchers and healthcare practitioners believe that the numbers of child fatalities resulting from abuse and neglect are grossly underreported (USDHHS, 2009). Factors that contribute to this include the following:

• Variation in state child fatality review processes

• Differences in death investigation systems and training of investigators

• The ease with which circumstances surrounding the death may be concealed

• Inaccurate determination of cause and manner of death (USDHHS, 2009)

Mercy et al. (2006) discussed the impact that the National Violent Death Reporting System may have on alleviating some of these discrepancies. By linking several reporting systems, police reports, death certificates, and child protective services reports, a more accurate account of intentional childhood deaths may be identified. The information learned will also influence prevention strategies and serve as a means of evaluating those efforts (CDC, 2008a, National Violent Death Reporting System).

Although an understanding of the statistics and their impact on screening for abuse and the many prevention efforts in communities is critical, it is the death investigation that lays the foundation for the determination of cause and manner of death. Thus, the death investigation affects the way law enforcement agencies and child protective services approach a case, the family, and others who may be involved in the death. Without a proper death investigation, an accurate cause and manner of death cannot be identified, resulting in inaccurate statistics from which to base all future interventions.

The forensic nurse examiner (FNE) is an important member of the infant and child death investigation team. These cases are medically and socially complicated investigations. A forensic nurse is equipped with the knowledge and expertise to assist in gathering the appropriate information to enable the forensic pathologist to determine the cause and manner of death. This chapter discusses child homicide and unexplained deaths. The role of the FNE and its bearing on the investigation are also explored. Although this is a difficult category of death to investigate, it must be done thoroughly and in a timely manner so perpetrators may be brought to justice.

Types of Intrafamilial Homicides

To appropriately investigate an infant or child death, forensic nurse death investigators (FNDIs) must first understand the type of death that they have been called to investigate. The type of death will guide the investigation from a medical and social standpoint.

Neonaticide

Neonaticide is defined as the killing of a neonate shortly after birth. In most cases, the death occurs on the first day of life (Jenny & Isaac, 2006). The practice of neonaticide has been observed since ancient times. Evidence of ritual killings of infants with deformities has been documented in Aztec, ancient Chinese, and some African cultures. Weak or deformed infants were killed so that they would not become a burden on society. This was also seen in ancient Greece and Rome. Other evidence indicates that males were often preferred over females, and neonaticide was an effective means of birth control (Craig, 2004). Neonaticide is more common in teenage mothers than in older mothers (Craig, 2004). Today, the perpetrator is often the mother (Jenny & Isaac, 2006). She has denied the existence of the pregnancy and often has psychotic or dissociative disorders (Jenny & Isaac, 2006).

A connection to poverty has not been established, nor has a presence of congenital anomalies been identified. However, two factors for neonaticide in today’s society have been postulated: these are failed pregnancy concealment and a means for late-term abortion (Craig, 2004). Other areas are being studied, but research is limited. Although neonaticide is almost exclusively a “female crime,” infanticide is commonly committed by either the mother or the father or stepfather (Jenny & Isaac, 2006).

Infanticide and filicide

The intentional killing of an infant aged one day to one year has been identified as infanticide (Stone, Steinmeyer, Dreher, & Krischer, 2005). One out of four of all infant homicides occur by two months of age, whereas 50% of infanticide cases occur by age four months (Jenny & Isaac, 2006).

There are many definitions of filicide. It has been described as the murder of a child or the murder of a child by the mother (Friedman & Resnick, 2007; Rouge-Maillart, Jousset, Gaudin, Bouju, & Penneau, 2005). These older children are often the victims of physical abuse. One study shows that the some of the most frequent mechanisms of filicide include head trauma, strangulation, suffocation, and drowning (Rouge-Maillart, 2005). Firearms may be used, but not in many cases. Reasons for filicide vary throughout history. They may encompass one or many of the following factors: disability, questionable paternity, gender, and a lack of resources (West, Hatters Friedman, & Resnick, 2009). Researchers developed a classification system that categorized the death based on the motives or circumstances:

• Altruistic. The child is killed because it is perceived to be in the child’s best interests (parental reasoning may be due to psychotic or nonpsychotic factors).

• Acutely psychotic filicide. The parent is psychotic and there is no rational motive.

• Unwanted child. The child is regarded as a hindrance.

• Accidental or fatal maltreatment. The child is unintentionally killed as the result of abuse or neglect.

• Spousal revenge. One spouse kills the child in an effort to get back at the other (West, et al. 2009).

No matter the motive, a thorough investigation must be conducted for every infant and child death.

Victims

The victims in these cases are obvious. They are the youngest and the most vulnerable. Children are dependent on adults for everything. This makes them susceptible to injury and death. The risk of a child becoming a victim of homicide is highest during the first year of life (Friedman & Resnick, 2007). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported the most current statistics regarding demographics of fatal child abuse victims. Females are at a higher risk than males. Caucasian children are murdered the most, with African Americans being second, and Hispanics ranking third (CDC, 2006). However, the true incidence is not known. Murders may be hidden and signs are misinterpreted, as investigations are often substandard. Many of these deaths are medically complicated, and law enforcement investigators are not educated in medical topics (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 1999; CDC, 2008c). Thus the data gathered do not accurately reflect the true numbers.

Perpetrators

It is difficult to comprehend that a parent would kill his or her own child. But it does happen and happens often. In neonaticide, the mother is often young and is attempting to conceal the pregnancy (Craig, 2004). The child is killed shortly after birth as the final act in disguising the pregnancy. It is difficult to identify women who are at risk to abuse or kill their child. Many mothers who have killed have a significant history of trauma. This past trauma may affect how they bond and approach the maternal role (Mugavin, 2008). Mental illness has also been found to play a part in infanticide and filicide. Mothers with schizophrenia and severe depression are at risk for killing their children (Levene & Bacon, 2004). These mothers may be in their twenties or thirties and unable to care for their children. The mothers are often described as being immature. Some have been found to be unemployed; some are suicidal and some are not suicidal (Rouge-Maillart, et al. 2005).

Unfortunately, attempting to determine the motive is often difficult when the parent describes the act as senseless (Rouge-Maillart, et al. 2005). Mugavin (2008) surmised that when there is a predisposition to mental illness or a traumatic history or substance abuse, one of these will possibly trigger the fatal event. That trigger may be the result of faulty thought processes in connection to revenge, sometimes against the other parent, the effects of substance abuse, desperation, or a mercy killing (Mugavin, 2008; Rouge-Maillart, 2005). The peak lifetime prevalence for psychiatric disorders is within the first three months after childbirth (Spinelli, 2004). This has important implications for prevention efforts. Physicians should be involved in screening for mental illness. The possibility for homicidal tendencies should not be underestimated (Rouge-Maillart, et al. 2005; Spinelli, 2004). Child homicide may be prevented, but it involves diligence on the part of the healthcare system to identify the signs and symptoms so that the mother may be treated.

Although the literature focuses on maternal filicide, studies have shown that paternal filicide occurs in approximately half of the cases (West, et al. 2009). Fathers are the most frequent perpetrators in the deaths of older children, whereas mothers are more likely to kill younger children (Adinkrah, 2003). In comparison to biological fathers, stepfathers are more likely to kill the stepchild (West, et al. 2009). Many of these deaths are the result of physical abuse. The father or stepfather did not intentionally set out to kill the child (West, et al. 2009). The child is often left in the care of the father or stepfather and over the course of beating the child for whatever reason, the child is fatally injured. Other factors associated with paternal filicide include unemployment, substance abuse, mental illness, and other situations such as the possibility of spousal separation (Marleau, Poulin, Webanck, Roy, & Laporte, 1999). Common methods used to kill include beatings, strangulation, suffocation, and drowning (West, et al. 2009). The literature is sparse, but the studies show many of the same circumstances are consistent in paternal filicide as in maternal filicide, meaning that prevention strategies for fathers or stepfathers are important and should be implemented.

Role of the Forensic Nurse in the Death Investigation

In the child death investigation, the FNE’s knowledge and expertise may impact the outcome of the medicolegal investigation. Forensic nurses may be employed in medical examiner’s offices as death investigators or elected as coroners or appointed as deputy coroners. Regardless of the title, the forensic nurse conducting the death investigation utilizes the nursing process. This type of investigation is especially complicated as homicides are often mistakenly classified as natural. The forensic nurse possesses a depth of knowledge that allows her or him to thoroughly navigate these complex issues. Knowledge of pathophysiology, toxicology, pharmacology, anatomy, physiology, and child development are critical. In addition, the forensic nurse has the ability to interact with sensitivity to the family to obtain critical medical and social information.

The forensic nurse performs the duties that are outlined in medical examiner law, coroner law, and the State Nurse Practice Act. Medical examiner (ME) and coroner law each delineate which deaths are reportable and provide the statutory authority to investigate. The Nurse Practice Act discusses where the nurse’s scope of practice begins and ends. It is in combining these laws and regulations that the forensic nurse is able to function in the death investigator role.

Whether the child died in a hospital, at a residence, at the daycare or babysitter’s residence, or at some other location, the evaluation of circumstances surrounding the death requires a systematic, scientific approach, which is applied through the use of the nursing process (Lynch, 2006). In approaching each death investigation in this manner, the forensic nurse is able to systematically and consistently obtain the necessary information for the pathologist to determine the cause and manner of death:

• Assessment. This involves observing all findings concerning the scene and the decedent. The forensic nurse obtains information from the responding law enforcement officials, the family, and any healthcare providers who cared for the child. Medical records are reviewed for ongoing medical issues that may have impacted the death.

• Planning. In this step, the forensic nurse outlines a plan of action that includes the location of the initial investigative efforts. For example, if the infant was found unresponsive at the residence but later died in the hospital, the forensic nurse must decide which of these two locations should be investigated first. If the family is still at the hospital, for example, it would make the most sense to go there to speak with them and the healthcare providers.

• Intervention. The scene and the decedent are documented. Documentation includes narrative descriptions of what is observed at the scene and the physical assessment of the deceased. Medical evidence is also recovered. The forensic nurse may notify relatives of the death, if needed, and make appropriate referrals to community support agencies as well.

• Evaluation. The forensic nurse discusses the scene investigation with the pathologist. Supplemental information is obtained as required. In addition, the pathologist shares the autopsy and toxicology results with the nurse. This may lead to further investigation (California State University, 2006 and Lynch, 2006).

Nurses functioning in this role must be skilled in both forensic science and nursing science. This is what makes them unique and invaluable to the forensic pathologist. The forensic nurse becomes the eyes and ears of the pathologist and ensures that a complete scene investigation is conducted. In particular to the child death investigation, the forensic nurse is able to speak with the family, obtain the medical and social history, and educate the family as to the medical examiner or coroner procedures. The FNE is also able to explain the cause and manner of death and their implications once determined.

As part of the multidisciplinary team, the forensic nurse is able to work closely with law enforcement and child protective services. Important information is shared and then relayed to the examining pathologist by the forensic nurse. Each agency is required to conduct a separate, parallel investigation into the child’s death. However, collaboration among the agencies is crucial for ensuring an appropriate outcome of the case. The FNE is a key member of the team.

Medicolegal Death Investigation

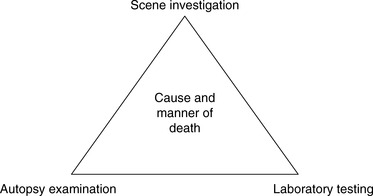

A child death investigation is emotionally charged. Each death must be examined thoroughly and appropriate testing completed. This type of investigation includes the scene investigation, autopsy examination, and laboratory studies (Corey, Hanzlick, Howard, Nelson, & Krous, 2007). Each component is dependent on the others, and missteps may negatively impact the determination of cause and manner of death (Fig. 18-1).

Time is critical. Therefore, the child death investigation must begin as soon as possible because scenes may change and potential evidence may be lost or destroyed (O’Neal, 2007). The forensic nurse must quickly choose which scene, if more than one, requires the immediate response. Communication between the FNDI and law enforcement is essential if the investigation is to run smoothly. The forensic nurse should never arrive at an unsecured scene without law enforcement. Safety is always the priority and must be considered first (CDC, 2007; U.S. Department of Justice [USDOJ], 1999).

The FNDI should first organize the scene response equipment and make sure all is in working order. Digital camera batteries should be fully charged. New batteries for the camera flash should be installed. All paperwork and any agency informational brochures should be packed in the scene response kit. Other adjuncts such as rulers, paper, gloves, and thermometer, both ambient and body, should be clean and functional (Box 18-1). Agency policy should dictate the specifics of the investigative procedure.

Box 18-1

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Forensic nurses who investigate deaths should have a scene kit that contains all but not limited to the following items:

• Scene kit (should be sturdy enough to withstand adverse weather conditions but allow the nurse to be organized; should have a handle or wheels)

• Camera

• Camera flash

• Extra batteries for camera and flash

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access