Section Eighteen Integumentary Procedures

PROCEDURE 134 Wound Cleansing and Irrigation

PROCEDURE 135 Wound Anesthesia: Local Infiltration andTopical Agents

PROCEDURE 137 Intravenous Regional Anesthesia

PROCEDURE 138 Fishhook Removal

PROCEDURE 139 Wound Care for Amputations

PROCEDURE 140 Surgical Tape Closures

PROCEDURE 134 Wound Cleansing and Irrigation

Wound cleansing and irrigation is also known as wound preparation or scrub.

Cleansing and irrigation are the fundamentals of good wound care. Although these steps can be the most tedious and time consuming, it is essential that all contaminants and devitalized tissue be removed before wound closure. The risk of infection depends on the location, mechanism, host, and care—the risk in a clean facial wound produced by an incision is less than 1%, whereas a dirty crush injury to the foot may have a greater than 20% risk (Simon & Hern, 2006). Factors contributing to the greatest risk of wound morbidity are prolonged time since injury; crush mechanism; deep, penetrating wounds; high-velocity missiles; and contamination with saliva, feces, soil, or other foreign matter (Simon & Hern, 2006).

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND CAUTIONS

1. Injuries that require special care include:

2. Soaking macerates the skin, and povidone-iodine causes tissue destruction. There is no evidence that soaking wounds in saline and povidone-iodine is of any benefit (Simon & Hern, 2006).

3. Excessive scrubbing and powerful irrigation can damage healthy tissue.

EQUIPMENT

PATIENT PREPARATION

1. Obtain a history, including time of injury, mechanism of injury, location and extent of injury, other injuries, and potential for the wound to be contaminated with soil or dirt. Assess the wound for foreign objects, such as clothing, grass, and glass. Also assess tetanus immunization status and potential for rabies (bite wounds).

2. Assess and document neurovascular status. Assess for adjacent bony injury or open fractures. Suspect damage to muscle and tendons if deep fascia is involved.

3. Obtain radiology studies as indicated to rule out the presence of foreign bodies, fractures, and air in joint spaces.

4. Anesthetize the area as indicated (see Procedures 135, 136, and 137).

5. Drape or undress the patient to protect clothing if extensive wound preparation and irrigation is planned.

PROCEDURAL STEPS

1. Maintain hemostasis by direct pressure. * Clamp and ligate vessels if necessary. Use a pneumatic tourniquet or a blood pressure cuff to help control bleeding during wound cleansing and repair, if prescribed by a physician.

2. Shaving is seldom indicated. Shaving causes many small wounds and skin nicks and increases the chance of infection. If hair removal is necessary, clip the hair close to the wound edge or smooth hair out of the way with lubricant or antibiotic ointment. Never shave eyebrows because realignment is difficult to achieve without the landmark hair, and the hair may not grow back completely.

3. Begin wound cleansing using sponges or brushes and a cleansing agent. Preparation should begin at the wound site and should move distally, encompassing a large area of skin surrounding the wound. For example, with hand lacerations, clean the hand and arm to the elbow. Continue until the wound is clean.

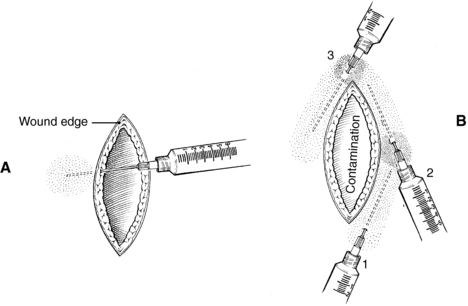

4. Irrigate wounds that are contaminated or those containing foreign bodies. Wound irrigation helps remove foreign bodies and dilutes bacteria. Irrigation is particularly important in bite wounds. Eight to 12 pounds per square inch of pressure is recommended to irrigate most wounds and can be achieved with an 19-G needle or plastic cannula and a 35-ml syringe held 2 inches from the wound (Figure 134-1) (Flippin, 2004). Mask, goggles, and gown are recommended in addition to a splash shield to prevent exposure to blood. Other options include a needle attached to a pressurized intravenous bag or tubing or a commercially available irrigation setup. Normal saline solution is most commonly used. Low-pressure irrigation (e.g., bulb syringe) is not effective.

The following formula for determining volume of irrigant has been associated with less than 0.01% wound infection (Daniels, 2003):

5. Abrasions with embedded foreign bodies (except glass) require careful wound preparation to remove the foreign bodies and prevent traumatic tattooing. Use surgical scrub brushes, sterile toothbrushes, and the point of a No. 11 or 15 blade for foreign body removal (Figure 134-2) (Flippin, 2004). Wounds with glass embedded require special evaluation and management; radiographic imaging may be needed. *Wound débridement may be necessary after anesthesia is completed.

6. Use petroleum jelly, antibiotic ointment, or mineral oil to facilitate tar removal. After application, allow tar to dissolve for 10 to 15 minutes before attempting removal. Repeat applications may be necessary.

COMPLICATIONS

1. The chance of infection, including cellulitis, soft tissue abscess, and osteomyelitis, increases in wounds to the hands and feet because of poor circulation in the extremities. Infection is also more common in dirty or old wounds. Bacterial growth begins in wounds after 3 hours.

2. Medications such as steroids and hormones may impair wound healing.

3. Other medical conditions may impair wound healing. Patients with diabetes, immune diseases, associated trauma, hypoxia, uremia, circulatory impairment, and infection, as well as the elderly, are all at increased risk for infection and delayed healing.

PATIENT TEACHING

1. High-risk patients should return for wound evaluation and dressing change within 24 to 48 hours.

2. The wound should be kept dry for the first 24 hours. The patient may then shower but should not soak in a tub. Wet dressings should be changed as soon as possible.

3. The wound should be cleaned four times a day with water and/or mild soap water. Crusted material should be gently removed with cotton swabs. Keeping crusted material off allows for quicker epithelialization.

4. Apply a light layer of topical antibiotic ointment after wound cleansing. A gauze dressing may be applied, depending on the wound location, especially for the first 48 hours.

5. Watch for bleeding, a wound that reopens, signs of circulatory compromise, or signs of infection (wound tenderness, redness, swelling, draining pus, fever). A minor amount of wound redness is normal.

6. Elevate the injured area as much as possible.

7. New wounds should not be exposed to the sun for 6 months. Permanent hyperpigmentation may result. Sun block is advisable, especially for facial wounds.

8. Complete wound healing and scar reduction may not be evident for 1 year.

Daniels J.H. Unpublished data. Sugarland, TX, 2003.

Flippin A.L. General principles of wound management. In: Reichman E.F., Simon R.R. Emergency medicine procedures. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004:693–709.

Simon B., Hern H.G. Wound management principles. In: Marx J.A., Hockberger R.S., Walls R.M., et al. Rosen’s emergency medicine: Concepts and clinical practice. 6th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2006:842–858.

PROCEDURE 135 Wound Anesthesia: Local Infiltration and Topical Agents

INDICATIONS

To provide local and topical anesthesia before:

• Removal of an embedded foreign body

• Incision and drainage of an abscess

• Invasive procedures, such as lumbar puncture or chest tube insertion

• Wound débridement and cleansing

• Insertion of nasal packing or nasal tubes

• Venous cannulation, venipuncture, or any needle insertion, including preinfiltration anesthesia

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND CAUTIONS

1. A known sensitivity or history of allergic reaction to a local anesthetic is a contraindication to its use. Patient-reported allergic reactions to amide preparations are rare (see Background Information).

2. The use of agents containing epinephrine may be contraindicated in patients with known peripheral vascular disease. Because of epinephrine’s vasoconstrictive action, it may delay healing and increase the risk of infection.

3. The use of epinephrine may be helpful in vascular areas, such as the face and scalp, to slow absorption and lower peak blood levels of anesthesia. Epinephrine also decreases bleeding at the site.

4. The use of epinephrine preparations is contraindicated in cartilaginous areas of the ear and nares and in areas served by end arteries (fingers, toes, and penis). Epinephrine also distorts and discolors the vermilion border of the lip and is contraindicated in lip lacerations that extend through the lip border.

5. Injection of anesthetic agents can distort wound margins, which may increase the complexity of plastics repair. Care should be used in flap-type lacerations to preserve vascularity of the flap by not injecting directly into the flap and avoiding the use of epinephrine-containing preparations.

6. Avoid rapid infiltration of the wound to decrease pain.

7. Amide preparations should be used cautiously in patients with liver disease (see Background Information).

8. The use of topical anesthetics containing cocaine (such as TAC) is not recommended because of potential adverse side effects and cost (Eidelman, Weiss, Enu, Lau, & Carr, 2005). Lidocaine (5%), epinephrine (1:2000), and tetracaine (1%) (LET) is a safe and effective alternative to TAC for topical use. LET can be used as a liquid or mixed with methylcellulose to form a gel. LET should be not used on mucous membranes, noses, pinna of the ear, fingers, toes, and penis.

9. Benzocaine is found in a wide variety of over-the-counter preparations for sunburn and abrasions. Toxic and allergic reactions are common. It may cause life-threatening methemoglobinemia.

10. Cetacaine spray has two principal ingredients: benzocaine and tetracaine. Tetracaine is rapidly absorbed by the pharynx and tracheobronchial tree and is long acting. Spray application greater than 2 seconds is contraindicated because of rapid mucosal absorption and potential toxicity of benzocaine and tetracaine.

11. Eutectic mixture of local anesthesia (EMLA) is an effective topic anesthetic for intact skin in the pediatric population. Local skin reactions are relatively common but are generally mild and transient, resolving after cream is removed. Methemoglobinemia may be caused by EMLA because of the metabolites of prilocaine, but this is rare when the preparation is used properly. EMLA should not be used in any infant younger than 3 months and in infants between ages 3 and 12 months old who are being treated with methemoglobinemia-inducing drugs, such as acetaminophen, phenobarbital, nitrites, sulfonamides, and antimalarial agents (McGee, 2004). Patients with anemia, respiratory or cardiovascular disease, or glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G-6-PD) or methemoglobin reductase deficiency are at higher risk for untoward effects (McGee, 2004).

12. When blood or central nervous system concentrations exceed safe limits of local anesthetics, systemic toxicity can occur (see Table 135-1). Epinephrine potentiates cardiac toxicity when added to a local anesthetic (Paris & Yealy, 2006).

Table 135-1 GUIDELINES FOR MAXIMUM DOSES OF COMMONLY USED AGENTS1

| Agent | Without Epinephrine | With Epinephrine |

|---|---|---|

| Lidocaine HCl2 | 3–5 mg/kg | 7 mg/kg |

| Mepivacaine HCl | 8 mg/kg | 7 mg/kg3 |

| Bupivacaine HCl4 | 1.5 mg/kg | 3 mg/kg |

1 All maximum doses should be reduced 20% to 25% in very young, old, and very sick patients.

3 Epinephrine adds to the potential cardiac toxicity of this drug.

From Marx, J. A., Hockberger, R. S., Walls, R. M., et al. (Eds.) (2006). Rosen‘s emergency medicine: Concepts and clinical practice [6th ed., p. 2932]. St Louis: Mosby; adapted from Stewart, R. D. [1988]. Local anesthesia. In P. M. Paris & R. D. Stewart [Eds.], Pain management in emergency medicine. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange.

EQUIPMENT

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

1. There are two general types of local anesthetics: ester compounds (procaine, cocaine, and tetracaine) and amide compounds (bupivacaine, lidocaine, and mepivacaine).

2. Amide compounds are metabolized in the liver. Ester compounds are hydrolyzed by the pseudocholinesterase in the serum. The lone exception is cocaine, which is excreted unchanged in the urine. All ester agents except cocaine share a common degradation pathway via serum to para-aminobenzoic acid, which can produce allergic or sensitizing reactions. Amide-type agents are believed to be incapable of stimulating antibody formation and so are noteworthy for their low evidence of sensitivity reactions. Reactions probably are toxic rather than allergic. Patients may be allergic, however, to the preservatives found in multiple-dose vials. Care must be taken to administer safe doses to avoid systemic toxicity.

3. The mechanism of local anesthesia is to decrease the rate and degree of depolarization and repolarization, decrease the conduction velocity, and prolong the refractory period of the neural action potential.

4. Nerve fibers are classified by their conduction velocity. Smaller fibers responsible for pain, temperature, and autonomic activity are affected rapidly by anesthetic. Local infiltration provides pain reduction without blockage of motor function.

5. All local anesthetic agents are vasodilators because of the relaxant effect on smooth muscles, with the exception of cocaine, which causes vasoconstriction.

6. Epinephrine added to the anesthetic solution helps with wound hemostasis and slows systemic absorption.

7. Similar to reactions to infiltration anesthesia, toxic reactions to topically applied anesthetics correlate with the peak blood levels that were achieved and not necessarily with the dose that was administered. Systemic absorption of a topical agent is more rapid and therefore achieves a higher peak blood level than the same dose given by infiltration.

PROCEDURAL STEPS

Topical Agents—Options

1. Apply a thick layer (1 to 2 grams [g]/10 cm2) of EMLA to intact skin under an occlusive dressing for approximately 30 minutes to 1 hour before a procedure. For minor procedures such as needle insertions, apply 2.5 g of EMLA over 20 to 25 cm2 for at least 1 hour. Preparation of two potential sites is recommended when an intravenous line is started, in the event of technical difficulties at the initial site. When a more painful procedure is anticipated, 2 g of EMLA/10 cm2 should be applied for at least 2 hours (McGee, 2004).

2. Apply lidocaine topically as a liquid, ointment, jelly, or viscous fluid (2% to 10%). Absorption is rapid. Do not exceed recommended dosage (maximum safe dosage is 250 to 300 mg) because total absorption cannot be calculated (McGee, 2004).

3. Use sprays containing benzocaine and tetracaine (e.g., Cetacaine, Hurricaine) primarily for oral procedures. Spray application should not exceed 2 seconds because toxicity including methemoglobinemia may result from excessive doses.

4. Anesthetic solutions: Use LET primarily for minor facial and scalp lacerations in lieu of injectable anesthetic, especially in children.

5. Assess adequacy of anesthesia by testing sharp-dull sensation and observing blanching before beginning the procedure.

Wound Infiltration

1. Several techniques can be used during wound infiltration to decrease pain. Slow administration of anesthetic intradermally through the inside margins of wound edges with small-gauge needles causes less pain.

2. Buffering lidocaine may reduce pain with injection. Lidocaine is buffered by adding 1 ml of sodium bicarbonate (8.4%) to every 10 ml of lidocaine solution. It remains effective after mixing for 1 week (Paris & Yealy, 2006).

3. Consider the anesthetic agent that most fits the patient’s need. A longer-acting local anesthetic (bupivacaine) may prevent the wound from having to be reinfiltrated, especially in a busy emergency department. Lidocaine has a more rapid onset, but it has a short duration of action. Attempt to avoid reinfiltration, especially in children or in wounds in which tissue viability is already a problem, such as in the face. If prolonged postanesthesia pain is anticipated, bupivacaine is useful.

4. Use the smallest possible needle for infiltration. A 27-G needle is usually adequate except for digital blocks, the scalp, or callused areas; in these situations, a 25-G needle may be required.

5. * Infiltrate wound edges through the dermis and not through the skin. Approaching the dermal layer directly from the inside edges of the cut margin of the wound is less painful. Continue to infiltrate as the needle passes through the dermis, injecting as you go. Some clinicians recommend injection through surrounding intact skin if the wound is grossly contaminated (Figure 135-1).

6. *As additional needle entry is needed, reenter through areas already infiltrated with anesthetic to lessen the pain of infiltration.

7. Assess sharp-dull sensation to ensure adequate anesthesia before beginning the procedure. If epinephrine has been used, observe the wound edges for blanching.

AGE-SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS

1. Calculate dosages carefully when administering local and topical anesthesia with children. Incorrect dosage calculations can cause significant side effects.

2. For extensive wound repair in children, consider the use of sedation (see Procedure 177) in conjunction with local anesthesia. If necessary, consider repair in a surgery or minor procedure area.

3. Viscous lidocaine should not be used for infants who are teething or have oral irritation, because they cannot expectorate well.

4. The use of distraction may be helpful in reducing pain associated with administration of local anesthesia.

COMPLICATIONS

1. Local reactions may include irritation, burning, erythema, and skin sloughing.

2. The major cause of systemic reactions is high serum levels. This is most common after topical applications to the trachea and upper airway passages because of rapid bronchial tree absorption.

3. Topical anesthesia of the nose, mouth, and pharynx may create an inadvertent suppression of the gag reflex, which may cause aspiration when combined with difficulty swallowing.

4. Resistance to injection or patient complaint of paresthesia may indicate intraneural injection. Withdraw the needle 1 to 2 mm and reinject to avoid disrupting nerve fibers.

5. Signs of central nervous system toxicity include apprehension, nausea, vomiting, tremor, light-headedness, muscle twitching, incoherent speech, and seizures. As toxicity increases, the anesthesia may interfere with electrical and mechanical function of the myocardium. Symptoms include a prolonged PR and QRS interval, bradycardia, hypotension, and asystole. Factors influencing toxicity include quantity and concentration of solution, presence or absence of epinephrine, vascularity of injection site, rate of absorption of drug, rate of destruction of drug, hypersensitivity of patient, and patient age, physical status, and weight.

6. Methemoglobinemia can occur related to the use of prilocaine or benzocaine. Signs of toxicity include dyspnea, lethargy, cyanosis, and coma.

7. True allergic reactions are rare and may occur in response to the preservatives found in multiple-dose vials. Symptoms include bronchospasm and urticaria. If epinephrine has been used, the patient may experience pallor, anxiety, palpitations, tachycardia, hypertension, and tachypnea.

PATIENT TEACHING

1. Instruct the patient when to expect the return of sensation.

2. Protect the area until sensation returns.

3. Provide analgesia when local anesthesia wears off.

4. Use of oral topical anesthetic agents, such as viscous lidocaine and benzocaine (including over-the-counter preparations), can cause difficulty swallowing. The medication should be used at the appropriate interval, and patients should be cautioned to avoid using it more frequently. It should be swished and expectorated within 1 to 2 minutes, not swallowed. Food and drink should be avoided for 1 hour after application to prevent aspiration.

Eidelman A., Weiss J, Enu I., Lau J., Carr D. Comparative efficacy and costs of various topical anesthetics for repair of dermal lacerations: A systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 2005;17:106–116.

McGee D. Local and topical anesthesia. In: Roberts J.R., Hedges J.R. Clinical procedures in emergency medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:533–551.

Paris P., Yealy D. Pain management. In: Marx J.A., Hockberger R.S., Walls R.M., et al. Rosen’s emergency medicine: Concepts and clinical practice. 6th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2006:2913–2935.

PROCEDURE 136 Digital Block

The digital nerve block is one of the most useful and commonly performed blocks in the emergency department and is considered superior to local infiltration in most circumstances (Kelly & Spektor, 2004). Wound infiltration may be difficult in the digit that has tight skin and can accept only a limited volume of anesthesia. Distortion of the anatomic landmarks or reduced capability for good wound approximation is also associated with local infiltration of a digit.

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND CAUTIONS

1. Known sensitivity or history of allergic reaction to local anesthetics is a contraindication.

2. Digital blocks should not be performed on the stump of digits under consideration for replantation.

3. The vascular status of the finger should be monitored during and after injection.

4. Preparations containing epinephrine have historically not been used for digital blocks although there have been several studies demonstrating epinephrine can be used as an adjunct for digital block anesthesia (Wilhelmi, Blackwell, & Miller, 2001).

5. Circumferential ring block (placing a ring of anesthesia in a circle around a finger) is generally contraindicated because of the risk of vasospasm and ischemia, except in the thumb and great toe.

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

Before using local anesthetic agents, the practitioner must understand the principal agents and the mechanisms of their actions (see Procedure 135). Knowledge of the anatomy of the hand and foot is essential for successful digital blocks.

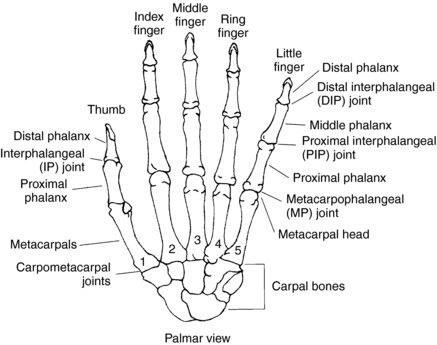

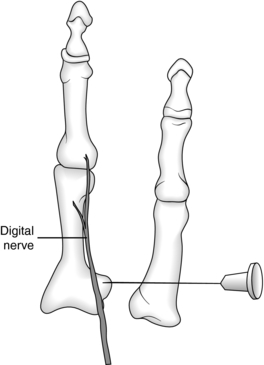

1. Hand and fingers (Figure 136-1):

PATIENT PREPARATION

1. Place the patient in a supine position with the hand or foot extended on a firm surface.

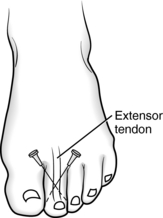

2. Assess and document sensation, circulation, and mobility distal to the wound. Mobility can be tested by testing grip, opposition of thumb and finger, and function of the interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints. Sensation can be effectively evaluated by the use of two-point discrimination using two blunt ends of a paper clip. Assess for tendon damage by having the patient flex and extend the finger or toe against pressure.

3. Suspect nerve injury if a digital artery laceration is present because of the nerve’s proximity to the artery. Do not attempt to clamp a digital artery because of the risk of damaging a digital nerve. Digital nerve laceration causes hemisensory loss to the finger.

PROCEDURAL STEPS

General Remarks for Any Technique

1. * Determine anesthetic of choice. Patients almost always benefit from the use of a longer-acting anesthetic, such as bupivacaine, especially if a lengthy repair is anticipated or the patient is expected to have pain after a shorter-acting anesthetic wears off. Consider using buffered lidocaine if a less lengthy repair is required. Digital blocks are less painful when buffered lidocaine is used.

2. *After infiltration of local anesthesia, gently massage the tissue to facilitate spread of anesthetic and increase absorption.

3. *Anesthesia is not effective if the periosteum has not been anesthetized. Introduce the needle down to the periosteum, and infiltrate closely to the bone.

4. *It is difficult to reach the nerves on both sides of a finger with a single injection. Separate injections on either side of the digit are usually needed.

5. Several approaches may be used to block the common digital nerves. The metacarpal and dorsal approaches are described here.

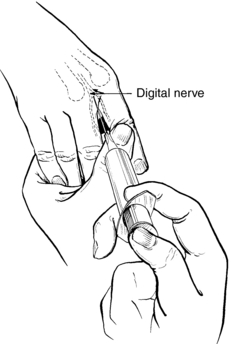

Fingers: Metacarpal Approach

1. *Palpate the metacarpal head approximately at the level of the distal palmar crease.

2. *Cleanse the palmar surface at the injection site with an antiseptic wipe.

3. *On the palmar surface of the hand, insert a 25-G needle perpendicular to the skin just medial or lateral to the metacarpal head into the web space (Figure 136-3).

4. *After aspirating to ensure vascular penetration has not occurred, inject 1 to 2 ml (depending on size of the finger) as the needle is advanced to the periosteum.

5. *Repeat step 4 on the opposite side of the metacarpal head. In total, 3 to 4 ml of anesthetic is required for effective anesthesia for both sides of the digit.

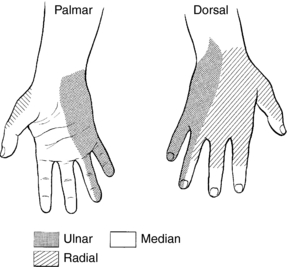

6. *The radial nerve innervates the dorsal surface of the index and middle finger (see Figure 136-2). It may also be necessary to infiltrate locally the dorsal side of the finger at the metacarpal head if injury is present to either of these fingers on the dorsal side of the hand.

Fingers: Dorsal Approach

1. *Cleanse dorsal surface with an antiseptic wipe.

2. *Inject anesthetic with a 25-G needle to raise a wheal of anesthesia on the dorsum of the finger near the base (Figure 136-4).

3. *Inject a total of 3 to 5 ml of anesthetic through the wheal by passing the needle downward until the needle is felt on the palmar surface (do not pierce the palmar skin).

4. *Subcutaneous infiltration is now accomplished at the base of the finger into the intraosseous spaces.

5. *For the index and little finger, the appropriate digital nerve is located in subcutaneous fatty tissue just anterior to the metacarpal head. Injection of anesthesia produces a half-ring wheal on the radial border of the index finger and on the ulnar border of the little finger.

Thumb

1. *Circumferential block is completed by placing a ring of anesthetic around the thumb. Block of the thumb is more difficult to attain because it is supplied by multiple branches of the radial and medial nerves.

2. *Insert the needle at the base of the thumb on the dorsal surface, and angle it toward the web space while injecting the anesthetic. Then reverse the needle direction and inject toward the opposite side of the thumb. Inject close to the periosteum, as noted earlier.

3. *Next, inject on the palmar side at the base of the thumb while angling the needle toward the web space. Then reverse the needle direction while injecting toward the opposite side of the thumb, thus completing the ring.

4. Effective anesthesia can usually be accomplished by injecting a total of 4 to 5 ml of anesthetic.

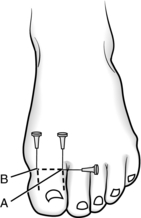

Toes

1. *Anesthesia of the great toe requires a band of anesthesia introduced via three separate injections (Figures 136-5 and 136-6). This block usually takes 5 to 10 minutes to take effect.

2. *To perform digital nerve blocks of other toes, introduce the needle at the dorsal side at the base of the midpoint of the involved toe (Figure 136-7).

3. *Angle the needle toward the bone, while slowly injecting anesthetic.

4. *Before withdrawing the needle, redirect the needle toward the opposite side of the toe, and infiltrate the second side of the toe.

5. Effective anesthesia can be achieved by injecting a total of 3 ml in the small toes and a total of 4 to 6 ml in the great toe.

AGE-SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS

1. Calculate anesthetic dosages and total anesthetic volume for the pediatric patient to avoid circulatory compromise of the digit.

2. The pediatric patient is not able to monitor return of sensation after digital block. Instruct the parents to assess circulation and limit activity until the return of expected normal sensation.

COMPLICATIONS

1. Avoid repeated jabbing while injecting to minimize hematoma formation and decrease postanesthesia neuritis.

2. Position the needle adjacent to the nerve. Intraneural infiltration should be suspected if excessive injection force is required. The patient may also complain of tingling or feeling a shock if the nerve is touched. Reposition the needle to avoid nerve injury.

3. Frequent aspiration helps avoid intravascular infiltration.

4. Vascular compromise may result if too large a volume of anesthesia is used. The amount required varies with each patient. An effective block can usually be accomplished with 3 to 4 ml in the digits, 4 to 5 ml in the thumb, and 4 to 6 ml in the great toe.

5. Digital block is used with finger injuries or infections. Local wound infiltration of the finger is contraindicated because of the risk of circulatory impairment.

6. Consider regional or general anesthesia if finger injury is severe or more than two fingers need digital blocks.

PATIENT TEACHING

1. Teach the patient how to assess circulatory compromise and motor or nerve impairment. Instruct the patient to return to the emergency department if compromise or impairment is suspected.

2. Adjacent fingers may also be numb because of the nerve pathways. While applying dressings to the digit, consider immobilizing the adjoining digit(s) depending on the severity of the injury.

3. Begin analgesia when anesthesia wears off, if needed. Instruct the patient when to expect return of sensation if lidocaine (1 to 2 hours) or bupivacaine (4 to 8 hours) is used. If numbness persists longer than 24 hours, instruct the patient to contact a physician or return to the emergency department.

4. Provide wound or fracture care instructions as indicated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree