Women’s Health

Lori A. Glenn

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Identify the major indicators of women’s health.

2. Examine prominent health problems among women of all age groups (i.e., from adolescence to old age).

3. Identify barriers to adequate health care for women.

4. Discuss issues related to reproductive health.

5. Explain the influence of public policy on women’s health.

6. Discuss issues and needs for increased research efforts focused on women’s health.

7. Apply the nursing process to women’s health concerns across all levels of prevention.

Key terms

breast cancer

cardiovascular disease

cesarean section

Civil Rights Act

domestic violence

ectopic pregnancy

Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA)

family planning

hypertension

life expectancy

maternal mortality

multiple family configurations

osteoporosis

pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

sexual harassment

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

To achieve “health for all” in the twenty-first century, health care services must be affordable and available to all. Although adequate health care for women is a key to realizing this goal, a significant number of women and their families face tremendous barriers in gaining access to health care. Additionally, knowledge deficits related to health promotion and disease prevention activities prevent women of all educational and socioeconomic levels from assuming responsibility for their own health and well-being.

Beginning in the 1970s, the women’s movement called for the reform of systems affecting women’s health. Women were encouraged to become involved as consumers of health services and as establishers of health policy. More women entered health professions in which they were previously underrepresented, and those in traditionally female-dominated professions, such as nursing and teaching, became more assertive in their demands to gain recognition for their contributions to society. Health care for women has evolved from the pelvic and breast focus to viewing the woman as a holistic being with specialized needs.

In “Preamble to a New Paradigm for Women’s Health,” Choi (1985) declared that collaboration and an interdisciplinary approach are necessary to meet the health care needs of women. She further stated that “essential to the development of health care for women are the concepts of health promotion, disease and accident prevention, education for self-care and responsibility, health risk identification and coordination for illness care when needed” (p. 14). To realize this paradigm, community health nurses must work with other health care professionals to formulate upstream strategies that modify the factors affecting women’s health. Many Healthy People 2020 objectives address health problems pertaining to women and include specific objectives and strategies to improve the health of this aggregate. The Healthy People 2020 boxes in this chapter present a small selection of these objectives. This chapter examines the health of women from adolescence to old age. It explores the major indicators of health, including specific health problems and the socioeconomic, sociocultural, and health policy issues surrounding women’s health. This chapter also discusses identification of current and future research aimed at improving the health of women. An understanding of these points will enable community health nurses to appropriately apply expertise in a community setting to help improve women’s health.

Major indicators of health

In the United States, data collected on major causes of death and illness appraise the health status of aggregates. These data are typically presented in terms of gender, age, or ethnicity and can help us interpret the levels of health in different groups. The primary indicators of health this chapter covers are life expectancy, mortality (i.e., death) rate, and morbidity (i.e., acute and chronic illness) rate.

There are 151.9 million women in the United States (Pleis, Lucas, and Ward, 2008). Of these women, 14% of those over the age of 18 years are considered in fair to poor health, while 18% have conditions that impair their daily functioning (Adams, Barnes, and Vickerie, 2007).

Many factors that lead to death and illness among women are preventable or avoidable. If certain conditions receive early detection and treatment, a significant positive influence on longevity and the quality of life could ensue. Recognition of patterns demonstrated by these indicators can address problems preventatively. This section presents an overview of these major indicators of health among women.

Life Expectancy

Except in a few countries, such as Bangladesh, Malawi, Niger, Pakistan, Qatar, and Zimbabwe, women typically experience greater longevity than their male counterparts (World Health Organization [WHO], 2004). For example, females born in the 1970s in the United States had an average life expectancy of 74.7 years, or 7.6 years longer than males born in the same year.

Life expectancy for Americans is at an all-time high, but the discrepancy between males and females remains. Males born in 2006 have a life expectancy of 76.5 years compared with 80.6 years for females. This suggests a trend toward narrowing the gap between male and female life expectancy (Heron et al., 2009). Ethnic/racial disparities in life expectancy unfortunately continued into the twenty-first century, as there is considerable variation between races. For example, black females gained an additional 7.1 years, rising from 69.4 years for those born in 1970 to 76.5 years in 2005. Although that is a significant gain, it falls behind the 80.8 years of life expectancy of white females born in that year (Heron et al., 2009).

Mortality Rate

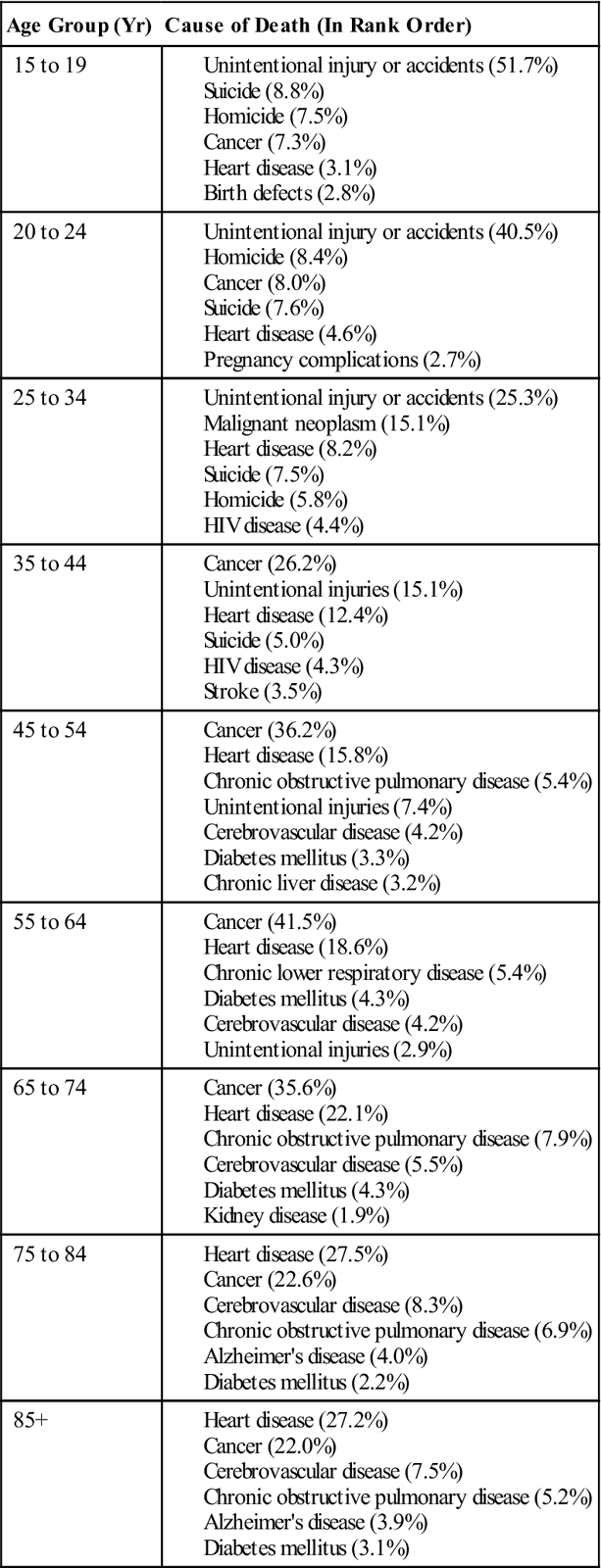

Table 17-1 lists the six major causes of death among American women in 2004 by age group (CDC, 2007c). As age increases, the leading causes of death change. In the adolescent to early adulthood years, the leading cause is unintentional injuries (i.e., motor vehicle accidents, drug overdose). As middle age approaches, cancer takes over as the number one cause. Finally after the age of 65 years, the rates of cancer and cardiovascular disease even out as number one.

TABLE 17-1

Five Leading Causes of Death Among American Women for all Races by Age Groups in 2005

| Age Group (Yr) | Cause of Death (In Rank Order) |

| 15 to 19 | |

| 20 to 24 | |

| 25 to 34 | |

| 35 to 44 | |

| 45 to 54 | |

| 55 to 64 | |

| 65 to 74 | |

| 75 to 84 | |

| 85+ |

Modified from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Leading cause of death in females, Women’s health, September 10, 2007a: www.cdc.gov/Women/lcod/04all.pdf. Accessed April 30, 2009.

Cardiovascular Disease

About one in four Americans has one or more forms of cardiovascular disease (CVD) (e.g., high blood pressure, coronary heart disease, stroke, congenital defects, and rheumatic heart disease). CVD accounts for about 35.3% of all deaths in the United States, or about one out of every 2.8 deaths. One in ten women under age 60 years has some form of CVD; the ratio increases to one in three after age 65 years. Black women are more likely to die of CVDs than white women. In 2005, the CVD death rate among white females was 230.4 per 100,000, compared with 319.7 per 100,000 for black females. Black women are also more likely to die of stroke than white women (60.7 per 100,000 and 44 per 100,000, respectively) (American Heart Association [AHA], 2009a).

Cardiovascular disease continues to be the number one overall killer of women. One out of every 2.4 deaths is from CVD, whereas one out of every 29 deaths is from breast cancer. In 2007, CVD caused more deaths among females (454,613, or 36.7%) than among males (409,867, or 34.2%) (AHA, 2009a). The overall number of deaths due to CVD decreased dramatically from 424.2 per 100,000 in 1950 to 273 per 100,000 in 2003.

Nevertheless, disparities continue related to prevention, diagnosis, and management of heart disease in women. After the age of 65 years, women are twice as likely to die because of heart disease as men (Vaccarino et al., 2003; American Heart Association, 2009b). Women have higher rates of complications after revascularization procedures (Jacobs, 2003) and higher rates of death after myocardial infarction (Wenger, 2004). This phenomenon exists because women display different symptoms of heart disease and are managed differently than men (Chang et al., 2003; Martin et al., 2004; Schulman et al., 1999). Physiologically, women have smaller arteries and higher rates of metabolic syndrome, diabetes, heart failure, and other comorbidities. They tend to be older at their first cardiovascular event, with more urgent and emergent presentations (Jacobs, 2003). These differences result in fewer preventative interventions, such as cholesterol screening, use of aspirin and other fibrinolytic therapy, and statin drugs to lower cholesterol (Downs, Clearfield, and Weis, 1998).

Rates of CVD among women can decline further when individuals become more aware of risk factors and accept responsibility for managing their own health and well-being (Kuehn, McMahon, and Creekmore, 1999). Concerned and motivated providers must encourage women to practice heart-healthy behaviors. In 2002, the American Heart Association launched the “Go Red” campaign for women and “The Heart Truth” program for health care providers designed to educate both about the unique features of women and heart disease.

Cancer

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States. Of deaths in America in 2008, 23% were due to cancer. (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2009). Further, cancer is expected to become the overall leading cause of death in the next decade (Stewart, King, Thompson, Friedman, Wingo, 2004).

Cancer rates appear to be increasing for a number of reasons including lifestyle choices (smoking, diet, sun exposure), increasing exposure to environmental carcinogens, and, probably most important, age. To illustrate, death rates from cancer among women have increased from 136 per 100,000 women in 1960 to 167.3 per 100,000 women in 2000 (Stewart, et al., 2004). The ACS estimates that 296,000 deaths will occur among women as a result of cancer in 2009 (ACS, 2008).

In 1987, lung cancer surpassed breast cancer as the leading cause of cancer deaths in women, and death rates increased sharply until about 1990. Lung cancer deaths leveled off, and in 2005 26% of cancer deaths in American women were attributed to lung cancer. Breast cancer was the second most common cause and resulted in 15% of all cancer deaths (ACS, 2008). Colorectal cancer, the third most frequent cause of cancer deaths, accounts for 9% of all cancer deaths and claims the lives of some 28,000 women annually.

Other female-specific cancers include ovarian cancer (fifth most common cancer), uterine cancer (sixth most common cancer), and cervical cancer. Cervical cancer, in particular, has received considerable attention of late as it has been determined that 90% of women with cervical cancer have evidence of cervical infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) (ACS, 2009). In June 2006, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) licensed Gardasil (Merck & Co., Inc.), the first vaccine to prevent HPV infection (CDC, 2007b; FDA, 2006). Since approval, more than 7 million doses have been given (CDC, 2007b). Gardasil has been shown to be highly effective in preventing the most common types of HPV infection and was approved for use in females between 9 and 26 years of age. For additional information consult the CDC’s website (www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/Vaccines/HPV/gardasil.html).

The good news is that healthy lifestyle changes and early detection and intervention have contributed to the decrease in mortality rates from some cancers. For example, the death rate for colorectal cancer has been decreasing for the past 15 years because of early detection and treatment. Lung cancer deaths are beginning to show a slight decline that parallels a decreased incidence of smoking by women over the age of 18 years (ACS, 2009).

Five-year survival rates vary according to the type of cancer and stage at diagnosis. For instance, the 5-year survival rate for all clients with lung cancer is only 18%. For localized breast cancer, it is 98%, decreasing to 23% when diagnosed with distant metastases. Of cancers related to the reproductive tract, ovarian cancer has the lowest survival rate, as only around 46% of women survive for 5 years. When the cancer is diagnosed at an early stage, 5-year survival rate for women with colon cancer is 91% and for those with rectal cancer it is 89% (National Cancer Institute, 2009).

Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are major factors in surviving many types of cancer. According to the ACS (2008) this includes routine cervical cancer screening with Pap smear and HPV tests beginning 3 years after the onset of intercourse, and continuing annually. After age 30 years, women with three negative annual Pap tests can be screened every 3 years. Breast cancer screenings include regular self breast examination and annual clinical breast exam, with the addition of a mammogram after the age of 40 years or sooner with increased risk of hereditary breast cancer. Colorectal cancer screenings include annual fecal occult blood tests along with sigmoidoscopy every 5 years or colonoscopy every 10 years (ACS, 2008).

Certain health choices may reduce an individual’s risk of cancer. All women need to avoid health-deteriorating practices and replace them with health-promoting behaviors. Women could reduce their risk for cancer by never smoking or by quitting if they already use tobacco products. Eating a nutritious, plant-focused, high-fiber diet, along with adopting a physically active lifestyle and maintaining a healthy body weight, protect against both heart disease and many cancers. Nutrition guidelines include avoiding salt-cured, smoked, nitrite-containing, and charred foods, high-fat food, and excessive alcohol (Rhodes, 2002; Vogel, 2003). Obesity has been associated with an increased risk for cancers such as colon and rectum, endometrium, and breast (ACS, 2008). Finally, the practice of safe sex has been shown to decrease the spread of cancer associated with sexually transmitted diseases such as HPV, hepatitis B and C, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Community health nurses must encourage all females (i.e., from childhood to old age) to adopt these healthy lifestyle choices and pursue early cancer detection. Community health nurses play a major role in providing cancer control services that should be culturally sensitive and appropriate to the targeted aggregate. If providers and clients applied everything known about cancer prevention, approximately two thirds of cancer cases would not occur.

Diabetes

In 2008, the number of patients with diabetes in the United States reached 24 million, or 8% of the population, with 25% of the population over 60 years of age being affected (CDC, 2008e). From 2003 to 2006, the number of patients with diagnosed diabetes had risen by 7.8%, especially among women (Cheung, Ong, and Cherny, 2009), although the number of men affected has exceeded women since 2006 (CDC, 2009a).

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic disease that causes premature death of many women and overall ranks sixth in mortality among that group, highest after the age of 45 years (CDC, 2007c). Diabetes ranks fourth as the cause of death among several aggregates, including Native American, black, and Asian, and is fifth among Hispanics (National Center for Health Statistics, 2004).

In addition to being a serious illness in itself, diabetes is a risk factor for the development of CVD; furthermore, it dramatically influences the severity and course of the CVD. In death certificates from 2004 where the cause of death was related to diabetes, 68% also listed CVD and 16% also listed stroke (CDC, 2008e). When comparing men and women with diabetes, of those who have myocardial infarction before age 65 years, women are more likely to have long-term health problems and to die (Norhammar et al., 2008). The good news is that the number of women hospitalized for diabetes has dropped, indicating that better management with tighter control of blood glucose has decreased complications (CDC, 2008c). The community health nurse is an important resource for supporting the tight control of diabetes to prevent its complications. An upstream approach to this problem includes helping women maintain a desirable weight throughout life in an effort to avoid nutrition-related causes of death, such as diabetes and CVD.

Maternal Mortality

According to the Safe Motherhood Organization (2005), complications of pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of disability and death among women between the ages of 14 and 49 years. In 2005, 536,000 women died, mostly in developing countries. Forty percent of women have complications during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period; 15% are life-threatening problems.

Before 2003, maternal mortality was the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days after termination of pregnancy. The U.S. Standard Certificate of Death and the WHO’s ICD-10 revised those guidelines in 2003 to include late causes of maternal death, defined as greater than 42 days but less than 1 year after the end of the pregnancy (Hoyert, 2007; WHO, 2007). The duration and the site of the pregnancy are irrelevant; causes are defined as related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.

It is important for community health nurses to be aware of the global situation surrounding maternal mortality. For each woman who dies in the developed world, 99 will die in the developing world (WHO, 2000), demonstrating that wide gaps continue to exist in the availability and quality of reproductive health care services globally.

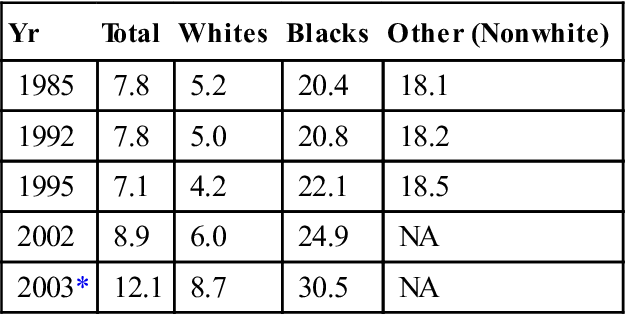

The United States ranks seventeenth in maternal mortality among all nations. In 2005 the rate of maternal death was 12.1 per 100,000 pregnancies (Department of Reproductive Health and Research, 2005). Reduction of maternal mortality is one of the Healthy People 2020 objectives for the United States.

Beginning in the 1950s, maternal mortality rates began to decline in the United States because of the use of blood transfusions, antimicrobial drugs, and the maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balance during serious complications of pregnancy and birth. The development of obstetric training programs and obstetric anesthesia programs was also important.

Racial discrepancy persists, however, in maternal mortality rates as in life expectancy. Table 17-2 illustrates how nonwhite women have a significantly higher incidence of death during pregnancy than whites. The gap in maternal mortality rates between black and white women has widened over the past several decades. Early in the twentieth century, black women were two times more likely to die of pregnancy-related complications than white women. Currently, black women are nearly four times more likely to die than white women (CDC, 2007c). Major risk factors for maternal death include lack of antepartal care and family planning services, inadequate health education, and poor nutrition. An additional risk factor, regardless of race, is advancing age. Women aged 40 years and older have over three times the risk of dying of a pregnancy-related cause as women aged 30 to 39 years (National Center for Health Statistics, 2007). Intrinsic maternal factors, such as increasing frequency of hypertension and a greater likelihood of uterine hemorrhage, help explain this increase in the mortality rate among older mothers.

TABLE 17-2

Maternal Mortality Rate per 100,000 Live Births—Selected Years

| Yr | Total | Whites | Blacks | Other (Nonwhite) |

| 1985 | 7.8 | 5.2 | 20.4 | 18.1 |

| 1992 | 7.8 | 5.0 | 20.8 | 18.2 |

| 1995 | 7.1 | 4.2 | 22.1 | 18.5 |

| 2002 | 8.9 | 6.0 | 24.9 | NA |

| 2003* | 12.1 | 8.7 | 30.5 | NA |

*Includes the category of “late maternal deaths and sequelae of late maternal deaths” for the first time.

From Hoyert DL: Maternal mortality and related concepts, National Center for Health Statistics, Vital Health Stat 3(33), p 10, 2007.

In 2005, maternal mortality was 15.1 per 100,000 live births, up from 12 per 100,000 in 2003 in the United States. Historically, the leading cause of maternal death is pulmonary embolism (17%), followed by pregnancy-induced hypertension, ectopic pregnancy, hemorrhage, stroke, and anesthesia (Cunningham et al., 2005). Of growing concern is the increasing cesarean section rate, incidence of maternal obesity, and increased age of mothers, which may be contributing to the rise in this rate (Kaiser, 2007). Death associated with legal surgical abortion is rare in the United States, with 33 reported in 2005 (Kung et al., 2008). Complications that result in death from legal abortion relate to the woman’s age, the type of procedure, the gestational age of the fetus, and general health problems at the time of the abortion (Cates, Ellertson, and Stewart, 2004).

A medical, or induced, method of abortion using mifepristone (i.e., RU-486), an antiprogestin medication, together with prostaglandins has been used in the United States since September 2000. This method is as effective as surgical abortion and is considered a safe alternative to surgical abortion in pregnancies of less than 49 days (7 weeks). In 2005, 9.9% of the 820,151 legal abortions in the United States employed this method. Curettage as an abortion procedure is still the most widely used (Gamble et al., 2008).

Abortion is a controversial issue for providers and for the women in their care. Adequate access to affordable family planning services is key to decreasing the need for elective abortions. Consider this quote from Dr. Joycelyn Elders: “I never knew a woman who needed an abortion who wasn’t already pregnant” (Elders, 2009). Nurses must continue to keep abreast of all available pregnancy prevention and termination options to provide the best counsel for women.

According to the CDC (2003), ectopic pregnancy is the leading cause of maternal death in the first trimester, accounting for 13% of maternal deaths. Since the 1980s, the incidence of ectopic pregnancy has increased fourfold to 11.3 per 1000 pregnancies among women 15 to 44 years of age. Racial discrepancy is evident and yields a rate of 14.7 per 1000 among nonwhites compared with 10.3 per 1000 among whites. This disparity continues to increase throughout the reproductive years of nonwhite women, possibly because sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) are more frequently diagnosed among nonwhite women, and these clients have less access to health care.

The most significant risk for ectopic pregnancy is previous pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) or salpingitis. Early diagnosis and treatment greatly reduce the mortality rate. Prevention interventions for women at risk for acquiring STDs are critical in reducing a woman’s risk for an ectopic pregnancy. An important task of health care providers is to educate women and men on methods to reduce sexual health risk-taking behaviors. Additional risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include tubal pathology, previous ectopic pregnancy, tubal surgery, and the use of intrauterine contraceptive devices.

Morbidity Rate

Hospitalizations

The 2008 National Hospital Discharge Survey (CDC) reported that more women than men are hospitalized each year in the United States. Pneumonia resulted in an average hospital stay of 5.6 days, which occurred most frequently among women aged 65 years or older. Fractures accounted for an average of 5.8 days, malignant neoplasms for an average 6.7 days, and diseases of the heart for an average 4.7 days. The number one reason for hospitalization was childbirth, followed by circulatory, digestive, respiratory diseases, and finally injury or poisoning. The length of hospitalization after childbirth has increased along with the C-section rate since 1995 (DeFrances et al., 2006).

The prospective payment system for hospitalization resulted in an increased demand for skilled nursing services in the home. After hospitalization for several of these conditions, community health nurses may provide ongoing nursing care in the home by referral. Nurses practicing in home environments must be prepared to deliver high-tech and high-touch services. Chapter 33 discusses home health care in detail.

Chronic Conditions and Limitations

Women are more likely than men to be disabled from chronic conditions. Arthritis and rheumatism, hypertension, and impairment of the back or spine decrease women’s activity level more often than they affect their male counterparts. In fact, twice as many women (24.3%) as men (11.5%) are limited in activity from arthritis and rheumatism. Women are more likely than men to have difficulty performing activities such as walking, bathing or showering, preparing meals, and doing housework (CDC, 2009d).

Functional limitations may require home health care that community health nurses supervise and deliver. Nurses plan and implement interventions based on functional assessments. The care plan facilitates optimal resumption of the individual’s independence in personal care activities.

Surgery

Women are more likely than men to have surgery. Hysterectomy is the second most frequently performed major surgical procedure among women of reproductive age after C-section. Approximately 600,000 hysterectomies are performed each year (CDC, 2008g). Hysterectomy rates for women in the South are slightly higher than those in the Northeast (6.3 and 4.9 per 1000 women, respectively). Overall, rates of hysterectomy have decreased from 5.4 to 5.1 per 100 in the years 2000 to 2004 (Whiteman and Hillis, 2008).

The most common reason for hysterectomy is uterine fibroids or leiomyoma, which contributes to more than one third of all such surgeries, but considerably more for blacks (68%) than for whites (33%) (CDC, 2008g). White women more often have a diagnosis of endometriosis and uterine prolapse, which are the second and third most common reasons for hysterectomy. Hysterectomy rates are the highest in women aged 40 to 44 years (CDC, 2008g).

Optional procedures are becoming available to women. Myomectomy, or removing only the tumors with repair of the uterus, uterine artery ablation, and the use of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone to shrink the tumors can decrease the need for hysterectomy, but women may not know about these alternatives. Community health nurses function as advocates for women and can provide health education programs related to alternatives to hysterectomy, indications for hysterectomy and oophorectomy (i.e., removal of ovaries), and information regarding the type of surgical approach and the purpose of a second opinion. Second opinions and higher levels of education tend to decrease the rate of hysterectomies (Finkel and Finkel, 1990).

Birth by cesarean section is the most prevalent surgical procedure undergone by women in the United States and accounts for 32% of births. This rate has gone up more than 50% since 1996 (Hamilton, Martin, and Ventura, 2009). Several factors contribute to the high rates of C-section, including physician fear of malpractice suits, routine use of early induction of labor, and epidural anesthesia. The technology of fetal monitoring has been shown to increase the C-section rate without improving neonatal outcomes. Consumer demand has also played a part in this trend, as parents expect that the latest technological advances and advanced medical training can guarantee the “perfect baby” and report the procedure as attractive for its convenience and perceived safety. C-section is also thought of as a way to preserve the pelvic floor, despite no evidence to support this effect. C-section is a lifesaving procedure, yet should be performed judiciously for women and their babies who are at risk for life-threatening complications without the procedure. C-section involves the risks of any major surgery such as hemorrhage, infection, damage to adjacent structures, and those risks associated with anesthesia. Long-term sequelae for women include pelvic pain, along with formation of adhesions and placental abnormalities that lead to complications in subsequent pregnancies. Risks to the neonate include higher incidence of persistent pulmonary hypertension and respiratory diseases (Levine et al., 2001). Routine, high rates of C-section are not shown to improve outcomes for either mother or baby (American College of Nurse Midwives, 2005). Women should be made aware of the risks involved with interventions associated with birth and educated on how to best select their place of birth.

Mental Health

The most frequently occurring interruption in women’s mental health relates to depression. Well-controlled epidemiological studies consistently demonstrate that women experience depression at two to three times the rate of men (American Psychological Association, 2005). Symptoms of depression include depressed mood, apathy, anxiety, irritability, and thoughts of death and suicide (Evans et al., 1999). Unique to women are atypical symptoms including anxiety, increased appetite, weight gain, and somatic complaints along with increased rates of comorbid conditions. Women are more likely to attempt suicide but less likely to be successful (Urbanic, 2009). Women with socioeconomic barriers such as lower income and lower educational levels, racial/ethnic discrimination, unemployment, poor health, single parenthood, and high-stress jobs are at greater risk for depression than women with higher educational levels or higher economic status. Other risk factors include childhood negligence and abuse, parental death, negligence, and alcoholism (Urbanic, 2009).

Nurses practicing in community health settings should be aware of the signs and symptoms of depression and identify referral sources for professional help within the community. The nurse needs also to be aware of the impact a mother’s depression may have on her child’s development and family functioning. A woman experiencing depression may display some signs and symptoms listed in Box 17-1.

Social factors affecting women’s health

Health Care Access

In 2008, 14.7% of the U.S. population, or 43.1 million U.S. citizens, lacked health insurance coverage, with 19.7% (37.1 million) of persons between ages 18-64 reporting lack of health care insurance (CDC, 2009e). Owing to the nature of their employment, women frequently lack health insurance but may not be eligible for Medicaid benefits because their income is too high. Young adults (i.e., those between ages 16 and 24 years) make up approximately 50% of individuals without health insurance. Lacking economic means for meeting the costs of health care, these women are not likely to seek health care until they or a family member is in acute distress. Others may rely on home remedies, over-the-counter drugs, or folk healers for health care. Older adults, who are usually covered by Medicare, may also delay seeking health care. Older women on fixed incomes may have difficulty meeting co-payments required by Medicare and paying for prescription medications. Many senior citizens have paid hospitalization insurance premiums for policies that fail to meet the gap.

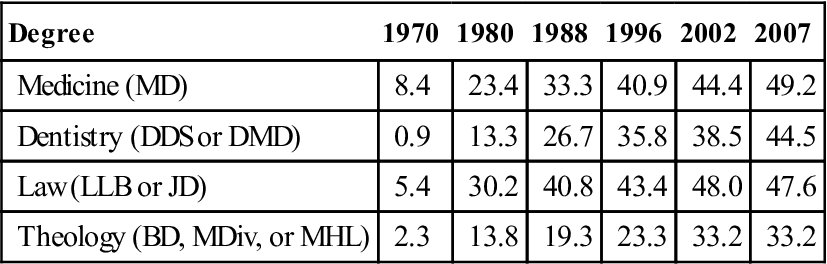

Education and Work

In the workplace, women traditionally predominate as secretaries, administrative assistants, registered nurses, teachers, cashiers, and retail sales people. However, in the 1980s, more women began to enter professions traditionally held by men (e.g., lawyers, physicians, and dentists), and in 2008, more than half (51%) of young professionals were women (U.S. Department of Labor, 2008). In 1970, 55.4% of all women aged 25 or older were high school graduates compared with 81.6% in 1995 and 85% in 2003. Of this same age group, 25.7% had completed college, which was more than three times the 1970 rate of 8.1% (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008a). An increasing number of women earned degrees in traditionally male-dominated professions. Table 17-3 reflects recent changes occurring in percentages of women receiving degrees in medicine, dentistry, law, and theology.

TABLE 17-3

Percentages of Degrees Received by Women

| Degree | 1970 | 1980 | 1988 | 1996 | 2002 | 2007 |

| Medicine (MD) | 8.4 | 23.4 | 33.3 | 40.9 | 44.4 | 49.2 |

| Dentistry (DDS or DMD) | 0.9 | 13.3 | 26.7 | 35.8 | 38.5 | 44.5 |

| Law (LLB or JD) | 5.4 | 30.2 | 40.8 | 43.4 | 48.0 | 47.6 |

| Theology (BD, MDiv, or MHL) | 2.3 | 13.8 | 19.3 | 23.3 | 33.2 | 33.2 |

From US Department of Education: Digest of education statistics, Washington, DC, 2008, The Author.

Employment and Wages

In 2008, 46.5% of the workforce were women. In addition, more than half (62%) of women with young children (younger than 6 years) were working outside the home (U.S. Department of Labor, 2005). In 1950, only 12% of women were combining these roles (Chadwick and Heaton, 1992).

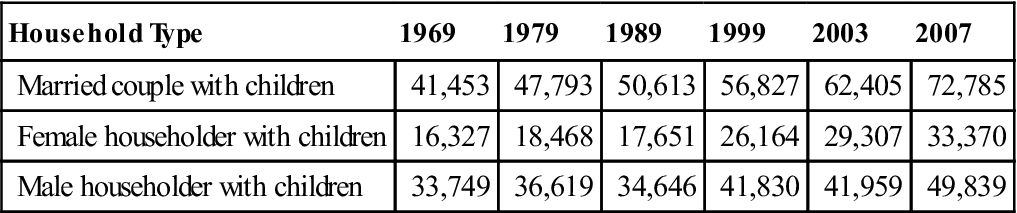

Several questions concern women’s health and well-being related to employment issues. A review of female-dominated versus male-dominated jobs discloses inequalities in wage and salary scales; despite the diminishing gap between women’s and men’s incomes, there is still much room for improvement. Table 17-4 depicts median annual earnings by type of household by sex and ethnicity for both men and women (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008b). Disparities in income based on sex are clear.

TABLE 17-4

Median Annual Earnings (In Dollars) by Type of Household: 1969, 1979, 1989, 1999, 2003, and 2007

| Household Type | 1969 | 1979 | 1989 | 1999 | 2003 | 2007 |

| Married couple with children | 41,453 | 47,793 | 50,613 | 56,827 | 62,405 | 72,785 |

| Female householder with children | 16,327 | 18,468 | 17,651 | 26,164 | 29,307 | 33,370 |

| Male householder with children | 33,749 | 36,619 | 34,646 | 41,830 | 41,959 | 49,839 |

From DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC, US Census Bureau: Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2007, Curr Popul Rep Consum Income, Washington, DC, 2008, US Government Printing Office: www.census.gov/prod/2008pubs/p60-235.pdf.

Women heads of households and their children are the poorest aggregate in the United States. This phenomenon is labeled “the feminization of poverty.” In 2005, the poverty rate for single female heads of household was 36.9%, compared with 17.6% for men (Thibos, Lavin-Loucks, and Martin, 2007). The nurse working with impoverished families should be aware of social services, child care programs, emergency services, and other resources for families in need. The community health nurse often needs to act as case manager and advocate for families with social service agencies and other public entities.

Working Women and Home Life

Added to inequalities outside the home are inequalities within the home. A working woman is less likely to have a spouse or partner help with the home and children. Even when a spouse or partner is present, the burdens of housework and child care usually fall more heavily on women, regardless of ethnicity. Mothers generally spend more time than fathers preparing meals and training and disciplining their children. These multiple-role demands and conflicting expectations contribute to stress (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005; Matthews and Power, 2002).

However, changes are occurring as younger and older men now report spending more time in family activities compared with middle-aged men. Blacks and Hispanics tend to spend a little more time working at family tasks than white men. Books and articles encourage wives and husbands to make their needs known, encouraging increased communication between partners. Marriage enrichment programs, often offered through churches and synagogues, teach couples how to communicate more effectively with each other, fostering equality between partners.

Family Configuration and Marital Status

Women are members of multiple family configurations (e.g., nuclear families, extended family units, single-parent units, families of group marriages, blended family units, adoptive family units, nonlegal heterosexual unions, and lesbian family units). This diversity causes changes in women’s roles within families. Whether or not they function in a traditional role, most women do whatever is necessary to maintain the integrity of their families. Early assessment of the strengths of family units by the community health nurse provides a database for positive nursing interventions established on upstream strategies to enhance each family’s level of health and well-being.

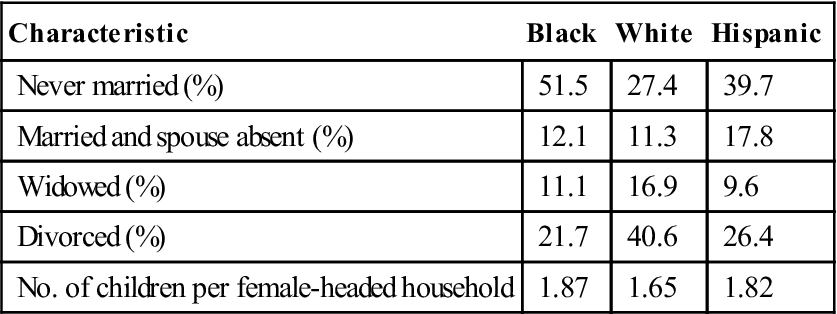

Many women are delaying marriage, and an increasing number are not marrying. Overall, marriage rates have remained stable perhaps because the increasing number of remarriages balances the declining rate of first marriages. When a relationship ends in divorce or separation, more women than men have the responsibility of providing for themselves and their children. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2007), single-parent households in 2006 represented 9% of all households with children, and one third of all children live with a single parent. Single mothers are most often the head of a single-parent family. Percentages of female single-parent households with children under the age of 18 years have been on the rise (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009) (Table 17-5). Even in the face of changing lifestyles, divorce, and increased mobility, which leads to long-distance relationships, most Americans report they remain connected to their extended families through parents, grandparents, siblings, aunts, and uncles.

TABLE 17-5

Characteristics of Black, White, and Hispanic Female-Headed Households: 2007

| Characteristic | Black | White | Hispanic |

| Never married (%) | 51.5 | 27.4 | 39.7 |

| Married and spouse absent (%) | 12.1 | 11.3 | 17.8 |

| Widowed (%) | 11.1 | 16.9 | 9.6 |

| Divorced (%) | 21.7 | 40.6 | 26.4 |

| No. of children per female-headed household | 1.87 | 1.65 | 1.82 |

Modified from US Census Bureau Current Population Reports and America’s Families and Living Arrangements: 2007, July 2008: www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/hh-fam/cps2007.html.

One contemporary family configuration involves single women with one or more adopted children. Single-parent adoptions are legal, and an increasing number of single women are becoming adoptive parents. An often-ignored family structure is one headed by a lesbian parent. Lesbians who become parents have needs similar to those of all mothers. Many cities have lesbian-gay parent groups that provide support, anticipatory guidance, and strategies for coping in society. However, lesbian women often neglect their own health. This self-neglect may be traced to hostile and rejecting attitudes of health care providers (Zeidenstein, 2004). However, the parents or guardians must remain healthy to ensure the child’s well-being.

Health promotion strategies for women

A woman’s ability to carry out her important roles can affect her entire family; therefore women should receive services that promote health and detect disease at an early stage. Early detection and improved treatments for disease allow women to return to work or remain working throughout the course of an illness. Although work is essential to the economic and social well-being of many women’s families, the workplace itself creates physical and social stress. As more women enter the workforce and face many of the same risks and stressors as men, it is not surprising that their formerly favorable mortality and morbidity rates have been worsening.

Many women seek information that will allow them to be in control of their own health. Since the early 1970s, women have met in self-help groups to develop a better understanding of their own health needs. Some of the health behaviors that women learn in self-help groups are the importance of nutrition and exercise, breast self-examination (BSE), pregnancy testing and contraceptive awareness; recognition of the early signs of vaginal infections and STDs; and awareness of the variations in female anatomy and physiology.

For women who desire to become more knowledgeable about their own health, there are books available in bookstores, public libraries, and among the holdings of traditional women’s groups such as sororities, federated women’s clubs, and others. An excellent resource for women is the FDA Consumer (www.fda.gov/fdac/), the official magazine of the FDA, which reports on studies that cover a variety of women’s health issues, such as mammography standards, menopause, treatment for STDs, eating disorders, infertility, cosmetic safety, silicone breast implants, and osteoporosis. Another resource is the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) Office on Women’s Health (www.WomensHealth.gov), which highlights positive health behaviors for women and girls. The community health nurse can use models such as Pender’s Health Promotion Model in teaching health behaviors that lead to general health promotion among women. Pender notes that health-promoting behaviors are directed toward sustaining or increasing the level of well-being, self-actualization, and fulfillment of a given individual or group (Pender, Murdaugh, and Parsons, 2006). However, because many models were developed for the middle class, they may not be useful to community health nurses working with low-income families.

Knowledge deficits related to body awareness prevail among all women, regardless of socioeconomic or educational level. Regardless of whether a group comprises college-educated professional women or blue-collar working women, many of the questions they pose are the same. For example, a woman may ask if she will menstruate after a hysterectomy, whether she should perform a BSE, or what she can do to prevent recurrent episodes of vaginitis. Nurses can play an instrumental role in helping women develop a greater sense of self-awareness. Furthermore, community health nurses can remove the mystery surrounding the woman’s body and encourage clients to ask previously unmentionable questions.

Acute Illness

Females report a greater incidence of acute conditions than males. This section describes several of the most common.

Urinary Tract Infection and Dysuria

By age 32 years, half of all women report a history of at least one urinary tract infection (UTI). Peak incidence in women is ages 20 to 24 years (Foxman and Brown, 2003). In every age group, adult women have a higher incidence of UTI than men, with an annual incidence of 12.6% compared with 3% among men. The higher incidence among women is attributed to differences in anatomy, which enhance the exposure to potential uropathogens and enhance the ability of these pathogens to colonize the urinary tract.

Women often experience dysuria, the sensation of pain, burning, or discomfort on urination. Dysuria accounts for 5% to 15% of visits to family physicians; approximately 25% of American women report acute dysuria every year. The symptom is most prevalent in women 25 to 54 years of age and in those who are sexually active. Although many physicians equate dysuria with UTI, it is actually a symptom that has many potential causes, infection being only one. Treatment with antibiotics may be inappropriate, except in carefully selected patients. Risk factors for both UTI and dysuria are female gender, advancing age, sexual activity, vaginitis, renal stone, and a history of sexual abuse, which can result in psychogenic dysuria (Bremnor and Sadovsky, 2002).

Diseases of the Reproductive Tract

Acute illnesses specific to the reproductive tract include conditions such as vulvovaginitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and toxic shock syndrome.

Vaginitis and vulvovaginitis

Vaginitis involves inflammation of the vaginal mucosa; vulvovaginitis refers to inflammation of the vulva as well. Both may start in girls before puberty and are more common than in women of reproductive age. These conditions continue to be frequent and often acute painful problems for which thousands of women seek relief annually. Symptoms include increase in vaginal discharge, itching, burning, dysuria, and dyspareunia. The physical examination may reveal vaginal and/or vulvar edema and erythema and a discharge that varies in color, odor, and consistency (Mou, 1999). Causes include candidiasis, trichomoniasis, bacteria, chemical irritants, allergens, and foreign bodies (Schuiling and Likis, 2006).

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) refers to acute infection of the upper genital tract structures in women, involving any or all of the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. It is estimated that more than 1 million women have an episode of acute PID each year (Epperly and Viera, 2005). PID is considered a community-acquired infection initiated by a sexually transmitted agent.

Women with PID often have atypical or no symptoms, which delay diagnosis and treatment. If symptomatic, a woman may have lower abdominal or pelvic pain, malodorous or new-onset vaginal discharge, abnormal uterine/vaginal bleeding, dyspareunia, dysuria, nausea, vomiting, and fever. The diagnosis of PID is often based on imprecise clinical findings. Definitive diagnosis is obtained best by laparoscopy, but this surgical procedure has risks and is hard to justify for mild cases. Despite this, diagnosis and treatment are critical to prevent serious reproductive sequelae, including ectopic pregnancy and infertility. Young women having lower abdominal pain and who are at risk for STDs should be treated with multiple antimicrobials that cover the potential microorganisms listed at the CDC STD website (www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2006/updated-regimens.htm). Their partner(s) should also receive treatment, and all parties should be instructed to abstain from intercourse until treatment is complete.

Toxic shock syndrome

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is a rare but serious disorder caused by toxins released by some strains of Staphylococcus aureus. TSS came to public attention in 1980 on the basis of a series of menstrually associated cases (Davis et al., 1980). The number of cases of menstrual TSS has declined from nine out of 100,000 women in 1980 to one out of 100,000 women since 1986 (CDC, 1990). It is most often associated with tampon use during menses; nonmenstrual TSS risk is increased for women who use vaginal barrier methods for birth control (Cates, Ellertson, and Stewart, 2004). The incidence of TSS has declined over the years owing to product changes and media warnings about tampon use (Farley, 1994). Although rare, TSS is a serious disorder of women’s health, and providers must make women aware of this acute illness and its potential consequences, encourage them to report symptoms early, and exercise caution when using tampons and vaginal family planning methods (Cates et al., 2004).

Chronic Illness

Included among chronic diseases that may affect a woman during her life span are coronary vascular disease and metabolic syndrome, hypertension, diabetes, arthritis, osteoporosis, and cancer.

Coronary Vascular Disease and Metabolic Syndrome

Evidence suggests that coronary vascular disease (and metabolic syndrome in most women are preventable. Coronary vascular disease is caused by arthrosclerosis, which results in buildup of plaque that narrows arteries, decreasing blood flow to the heart muscle. Metabolic syndrome is a group of risk factors that have been linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular events. These factors include abdominal obesity (waist circumference greater than 35 inches in women), dyslipidemia (elevated triglycerides and low high-density lipoprotein), insulin resistance, and elevated blood pressure. The underlying etiology of metabolic syndrome is related to the combination of inactivity, obesity, and genetics.

At-risk women will have nonmodifiable risk factors such as increasing age, race, gender, or family history of coronary vascular disease and diabetes. Where the greatest impact can be made is with the modifiable risk factors including

• Obesity

• Diet high in calories, total fats, cholesterol, refined carbohydrates, and sodium

• Stress

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Healthy People 2020

Healthy People 2020