Theris A. Touhy

Diseases affecting vision and hearing

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE

For quite a while now, I’ve been pretending. That it was just that I was tired. That the light was bad. But my eyes are really getting worse. I’m afraid to go to the doctor because I’m afraid of what he’ll say. Which is silly. Either there is something to be done. Or there is not. If it’s glasses, hallelujah, and help me find the money. If it’s an operation, see me through. If I am going blind, hold me. Help me put down the terror that rises in my gut at the word. Blind. There. I’ve said it. The ghost word that has been haunting me. Help me remember, if I have to walk in the dark, that I have had a lot of years of seeing clean and clear. I know the slender shape of a birch tree. I have seen thousands and thousands of things in my life. I can conjure them in my mind’s eye. No matter what happens, I shall not be without beautiful sights. It is just that I may have to settle for the ones I have already seen.

From Maclay E: Green winter: celebrations of old age, New York, 1977, Crowell. Copyright ©1977 Elise Maclay.

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

• Discuss the assessment and treatment of diseases of the eye and ear that may occur in older adults.

• Increase awareness of the resources available to assist elders with visual and hearing impairments.

Glossary

Drusen Yellow deposits under the retina, often found in people over 60 years of age.

Funduscopy Opthalmoscopic examination of the fundus of the eye.

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca Diminished tear production with age.

Lipofuscin Fatty brown pigment found in the tissues related to aging.

Tonometry The procedure used by eye care professionals to determine the intraocular pressure of the eye.

![]() evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

This chapter discusses diseases that affect vision and hearing in older adults and adaptations to enhance communication for those with vision and hearing impairments. Healthy People 2020 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2012) has set goals for vision and hearing (see the Healthy People boxes). To help the student understand more about the eye diseases discussed in this chapter, the following website provides a simulation of glaucoma, cataracts, macular degeneration, and diabetic retinopathy: http://www.visionsimulations.com/.

Vision

Blindness and visual impairment are among the 10 most common causes of disability in the United States and are associated with shorter life expectancy and lower quality of life. For older adults, visual problems have a negative impact on quality of life, equivalent to that of life-threatening conditions such as heart disease and cancer. The leading causes of visual impairment are diseases that are common in older adults: age-related macular degeneration (AMD), cataract, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy. Figure 16-1 shows the effect of vision loss from these diseases. Vision loss is becoming a major public health problem and is projected to increase substantially with the aging of the population (National Eye Institute, 2004). By the year 2020, the number of people who are blind or have low vision is projected to reach 5.5 million (USDHHS, 2012).

Older adults represent the vast majority of the visually impaired population. More than two thirds of those with visual impairment are over 65 years of age. Visual impairment among nursing home residents ranges anywhere from 3 to 15 times higher than for adults of the same age living in the community (Owsley et al., 2007). Racial and cultural disparities in vision impairment are significant. African Americans are twice as likely to be visually impaired than are white individuals of comparable socioeconomic status; Hispanics also have a higher risk of visual complications than the white population. A recent survey conducted in the United States reported that among all racial and ethnic groups participating in the survey, Hispanic respondents reported the lowest access to eye health information, knew the least about eye health, and were the least likely to have their eyes examined (National Eye Institute, 2008).

Clearly, prevention and treatment of eye diseases is an important priority for nurses and other health care professionals. The National Eye Health Education Program (NEHEP) of the National Eye Institute provides a program for health professionals with evidence-based tools and resources that can be used in community settings to educate older adults about eye health and maintaining healthy vision (www.nei.nih.gov/SeeWellToolkit). The program emphasizes the importance of annual dilated eye examinations for anyone over 50 years of age and stresses that eye diseases often have no warning signs or symptoms, so early detection is essential.

Diseases of the eye

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a leading cause of blindness and visual impairment in the United States, affecting as many as 2.2 million people. An additional 2 million are unaware they have the disease. There are no symptoms of glaucoma in the early stages of the disease. Types of glaucoma include congenital glaucoma, primary open-angle glaucoma, low tension or normal tension glaucoma, secondary glaucoma (complication of other medical conditions), and acute angle-closure glaucoma, which is an emergency. The etiology of glaucoma is variable and often unknown. However, when the natural fluids of the eye are blocked by ciliary muscle rigidity and the buildup of pressure, damage to the optic nerve occurs. Glaucoma can be bilateral, but it more commonly occurs in one eye.

Open-angle glaucoma accounts for about 80% of cases and is asymptomatic until very late in the disease, when there is a noticeable loss in visual fields. However, if detected early, glaucoma can usually be controlled and serious vision loss prevented. Signs of glaucoma can include headaches, poor vision in dim lighting, increased sensitivity to glare, “tired eyes,” impaired peripheral vision, a fixed and dilated pupil, and frequent changes in prescriptions for corrective lenses.

An acute attack of angle-closure glaucoma is characterized by a rapid rise in intraocular pressure (IOP) accompanied by redness and pain in and around the eye, severe headache, nausea and vomiting, and blurring of vision. It occurs when the path of the aqueous humor is blocked and intraocular pressure builds up to more than 50 mm Hg. If untreated, blindness can occur in 2 days. An iridectomy, however, can ease pressure. Many drugs with anticholinergic properties including antihistamines, stimulants, vasodilators, clonidine, and sympathomimetics, are particularly dangerous for patients predisposed to angle-closure glaucoma. Older people with glaucoma should be counseled to review all medications, both over-the-counter and prescribed, with their primary care provider.

Low tension or normal tension glaucoma is a type of glaucoma that also occurs in older adults. In this type, intraocular pressure is within normal range but there is damage to the optic nerve and narrowing of the visual fields. The cause is unknown, but risk factors include a family history of any kind of glaucoma, Japanese ancestry, and cardiovascular disease. Management consists of the same medications and surgical interventions that are used for chronic glaucoma (Glaucoma Research Foundation, 2008).

A family history of glaucoma, as well as diabetes, steroid use, and past eye injuries have been noted as risk factors for the development of glaucoma. Age is the single most important predictor of glaucoma, and older women are affected twice as frequently as older men. Among African Americans, glaucoma is the leading cause of blindness. African Americans develop glaucoma at younger ages, and the incidence of the disease is 5 times more common in African Americans than in whites and 15 times more likely to cause blindness. Factors contributing to this increased incidence include earlier onset of the disease as compared with other races, later detection of the disease, and economic and social barriers to treatment (National Eye Institute, 2010a). Research is ongoing to investigate the complex genetic and biological factors that cause glaucoma and to develop treatments that protect optic nerves from the damage that leads to vision loss (USDHHS, 2012).

Screening and treatment.

Adults over 65 years of age should have annual eye examinations, and those with medication-controlled glaucoma should be examined at least every 6 months. Annual screening is also recommended for African Americans and other individuals with a family history of glaucoma who are older than 40. A dilated eye examination and tonometry are necessary to diagnose glaucoma. These procedures can be performed by a primary care provider, optometrist, or a nurse practitioner, who will then refer the person to an ophthalmologist if glaucoma is suspected. Medicare pays for annual screening for glaucoma but only in high-risk patients.

Management of glaucoma involves medications (oral or topical eye drops) to decrease IOP and/or laser trabeculoplasty. Medications lower eye pressure either by decreasing the amount of aqueous fluid produced within the eye or by improving the flow through the drainage angle. Beta blockers are the first-line therapy for glaucoma, and the patient may need combinations of several types of eye drops. Usually medications can control glaucoma, but laser surgery treatments (trabeculoplasty) may be recommended for some types of glaucoma. Surgery is usually recommended only if necessary to prevent further damage to the optic nerve.

When caring for older adults in the hospital or long-term care settings, it is important to obtain a past medical history to determine if the person has glaucoma and to ensure that eye drops are given according to the person’s treatment regimen. Without the eye drops, eye pressure can rise and cause an acute exacerbation of glaucoma (Capezuti et al., 2008).

Cataracts

Cataracts are a prevalent disorder among older adults caused by oxidative damage to lens protein and fatty deposits (lipofuscin) in the ocular lens. By 80 years of age, more than half of all Americans either have a cataract or have had cataract surgery. When lens opacity reduces visual acuity to 20/30 or less in the central axis of vision, it is considered a cataract. Cataracts are categorized according to their location within the lens and are usually bilateral.

Cataracts are recognized by the clouding of the ordinarily clear ocular lens; the red reflex may be absent or may appear as a black area. The cardinal sign of cataracts is the appearance of halos around objects as light is diffused. Other common symptoms include blurring, decreased perception of light and color (giving a yellow tint to most things), and sensitivity to glare.

The most common causes of cataracts are heredity and advancing age. They may occur more frequently and at earlier ages in individuals who have been exposed to excessive sunlight, have poor dietary habits, diabetes, hypertension, kidney disease, eye trauma, or history of alcohol intake and tobacco use. There is some evidence that a high dietary intake of lutein and zeaxanthin, compounds found in yellow or dark leafy vegetables, as well as intake of vitamin E from food and supplements, appears to lower the risk of cataracts in women. Further research is indicated (Moeller et al., 2008).

When visual acuity decreases to 20/50 and the cataract affects safety or quality of life, surgery is recommended. Cataract surgery is the most common surgical procedure performed in the United States. Most often, cataract surgery involves only local anesthesia and is one of the most successful surgical procedures, with 95% of patients reporting excellent vision after surgery. The surgery involves removal of the lens and placement of a plastic intraocular lens (IOL). Cataract surgery is performed with local anesthesia on an outpatient basis, and the procedure has greatly improved with advances in surgical techniques.

Nursing interventions when caring for the person experiencing cataract surgery include preparing the individual for significant changes in vision and adaptation to light and insuring that the individual has received adequate counseling regarding realistic postsurgical expectations. Postsurgical teaching includes covering the need to avoid heavy lifting, straining, and bending at the waist. Eye drops may be prescribed to aid healing and prevent infection. If the person has bilateral cataracts, surgery is performed first on one eye with the second surgery on the other eye a month or so later to ensure healing.

Although race is not a factor in cataract formation, racial disparities exist in cataract surgery in the United States, with African-American Medicare recipients only 60% as likely as whites to undergo cataract surgery (Miller, 2008; Wilson & Eezzuduemhoi, 2005). Unfortunately, cataracts and other related eye diseases such as maculopathy, diabetic retinopathy, or glaucoma often occur simultaneously, which complicates the management of each.

Diabetic retinopathy

Diabetes has become an epidemic in the United States (see Chapter 17). Diabetic eye disease is a complication of diabetes and a leading cause of blindness. Diabetic retinopathy is a disease of the retinal microvasculature characterized by increased vessel permeability. Blood and lipid leakage leads to macular edema and hard exudates (composed of lipids). In advanced disease, new fragile blood vessels form that hemorrhage easily. Because of the vascular and cellular changes accompanying diabetes, there is often rapid worsening of other pathologic vision conditions as well.

There are no symptoms in the early stages of diabetic retinopathy. Estimates are that 40.8% of adults 40 years of age and older with diabetes have diabetic retinopathy, and the incidence increases with age. Most diabetic patients will develop diabetic retinopathy within 20 years of diagnosis. Prevalence rates for diabetes and diabetic retinopathy are higher among racially and culturally diverse individuals and among American Indian and Alaska Native populations (National Eye Institute, 2010b).

Screening and treatment.

There is little to no evidence of retinopathy until 3 to 5 years or more after the onset of diabetes. Early signs are seen in the funduscopic examination and include microaneurysms, flame-shaped hemorrhages, cotton wool spots, hard exudates, and dilated capillaries. Constant, strict control of blood glucose, cholesterol, and blood pressure and laser photocoagulation treatments can halt progression of the disease. Laser treatment can reduce vision loss in 50% of patients, and recent evidence suggests that treatment with various drugs may deliver a better outcome (USDHHS, 2012). Annual dilated funduscopic examination of the eye is recommended beginning 5 years after diagnosis of diabetes type 1 and at the time of diagnosis of diabetes type 2.

Macular degeneration

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of vision loss in Americans 60 years of age and older. The prevalence of AMD increases drastically with age, with more than 15% of white women over 80 years of age having the disease. Whites and Asian Americans are more likely to lose vision from AMD than African Americans. With the number of affected older adults projected to increase over the next 20 years, AMD has been called a growing epidemic (National Eye Institute, 2010c).

AMD is a degenerative eye disease that affects the macula, the central part of the eye responsible for clear central vision. The disease causes the progressive loss of central vision, leaving only peripheral vision intact. Early signs of AMD include blurred vision, difficulty reading and driving, increased need for bright light, colors that appear dim or gray, and an awareness of a blurry spot in the middle of vision.

AMD results from systemic changes in circulation, accumulation of cellular waste products, tissue atrophy, and growth of abnormal blood vessels in the choroid layer beneath the retina. Fibrous scarring disrupts nourishment of photoreceptor cells, causing their death and loss of central vision. The greatest risk factor for AMD is age. Although etiology is unknown, risk factors are thought to include genetic predisposition, smoking, obesity, family history, and excessive sunlight exposure.

There are two forms of macular degeneration, the “dry” form and the “wet” form. Dry AMD accounts for the majority of cases and rarely causes severe visual impairment, but can lead to the more aggressive wet AMD. Dry AMD generally affects both eyes, but vision can be lost in one eye while the other eye seems unaffected. One of the most common early signs is drusen. Drusen are yellow deposits under the retina and are often found in people over 60 years of age. The relationship between drusen and AMD is not clear, but an increase in the size or number of drusen increases the risk of developing either advanced AMD or wet AMD (National Eye Institute, 2010c).

Wet AMD occurs when abnormal blood vessels behind the retina start to grow under the macula. These new blood vessels are fragile and often leak blood and fluid, which raise the macula from its normal place at the back of the eye. With wet AMD, the severe loss of central vision can be rapid, and many people will be legally blind within 2 years of diagnosis. Peripheral vision usually remains normal, but the person will have difficulty seeing at a distance or doing detailed work such as sewing or reading. Faces may begin to blur, and it may become harder to distinguish colors. An early sign may be distortion that causes edges or lines to appear wavy.

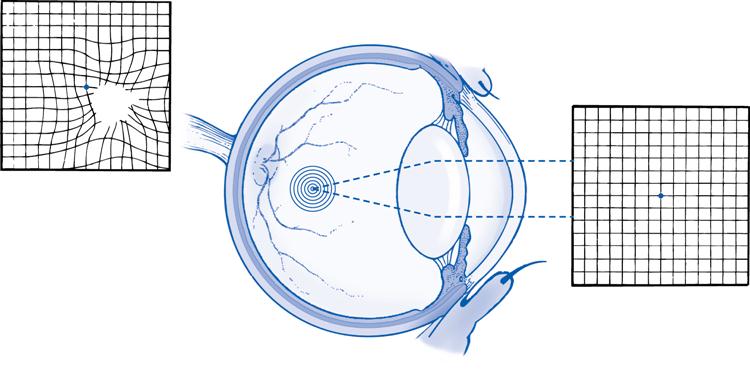

An Amsler grid is used to determine clarity of central vision (Figure 16-2). A perception of wavy lines is diagnostic of beginning macular degeneration, and vision loss can occur in days. In the advanced forms, the person may begin to see dark or empty spaces that block the center of vision. People with AMD are usually taught to test their eyes daily using the Amsler grid so that they will be aware of any changes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree