CHAPTER 15. Technology, skill development and empowerment in nursing

Alan Barnard

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

• explain the importance of technology for nursing practice and skills development

• describe characteristics associated with technology that are important for healthcare

• outline implications of technology for nursing care with specific reference to empowerment, and

• describe key principles and values important for fostering excellence in nursing practice.

NURSING AND TECHNOLOGY

This chapter considers the role and importance of technology for nursing practice, with specific reference to skill development and empowerment. Principles important to understanding technology are outlined and the implications of technology for nursing and healthcare are discussed, along with guiding principles and values important to appropriate integration of technology into clinical practice. It is argued that technology is a phenomenon that must be understood adequately to address the many challenges it presents for current and future nurses.

Technology influences the practice of nursing both from the perspective of what we do and how we understand ourselves as practitioners. Nurses talk about technology, develop skills and knowledge to apply technology, interpret technology, praise the qualities of the latest computer applications, worry about loss of human contact and work in a changing workplace. Technology is used, for example, to deliver accurate treatment, to hold water, to cover patients and to observe the internal workings of the human body. Technology advancement is linked to a range of experiences, including shorter length of admission to hospital, greater efficiency, changing skills and knowledge, alteration to employment patterns, specialisation and standardisation of care (Locsin, 2001, Rinard, 1996 and Sandelowski, 2000). These outcomes of technological development combined with the interests of dominant social groups, increasing legal liability and the maintenance of technology have produced healthcare practices that are focused sometimes on functionality, sameness, conformity, automation, safety, predictability and logical order.

Technology is significant to the history, contemporary practice and future of nursing. It has always been a part of nursing and in order to understand nursing as a discipline we need insight into the social, theoretical and practical implications that emerge as a result of our links with technology. Prior to the twentieth century, technical knowledge and skills developed by trial and error, and were passed down through generations via a practical and oral culture. Nurses relied on experience and faith. Technical skills included magical and aesthetic components that equated with moral and psychic life. Nursing practice relied less on scientific knowledge and explanation than on a personal and intuitive understanding developed and refined through practice (Barnard & Cushing 2001).

The rapid growth of scientific and technological knowledge has bought about enormous changes for nursing and healthcare over the past hundred years, and technology has figured prominently as both a protagonist for development and an influential partner in our practice. Technology remains integral to healthcare and has significantly influenced our workplace, not only in terms of the artefacts and resources we use, but also how we do things, how we organise ourselves as nurses and what we value. In fact, over 15 years ago Cooper (1993) warned that the process of technological change had advanced to such an extent that many areas of nursing practice had come to be defined by technology. For example, the haemodialysis machine is associated with renal nursing and the ventilator is associated with intensive care practice. The warning would appear to be confirmed as a result of an increasing emphasis on competency-based education and practice, which is linked directly to the use of technology(ies). But regardless of whether the warning of Cooper is proving to be entirely accurate, it is acknowledged widely that nurses in all specialties are required to manipulate a significant amount of technology and accept increasingly complex roles and responsibilities associated with its ongoing importance in healthcare (Barnard and Locsin, 2007 and Sandelowski, 1999a).

INTERPRETING TECHNOLOGY

The word technology (tech.nol.ogy) refers to the practical arts, specific implements and the knowledge and/or activity of a group (i.e. technologist). The phenomenon is subject to varied and sometimes inadequate explanation in nursing and is influenced by social status, culture, gender and politics (Barnard, 2002, Pelletier, 1989 and Rinard, 1996). Technology is more than the sum of things we use in healthcare. It has characteristic features that include the development of skills, knowledge and the incorporation of social arrangements and values (Feenberg, 1995, Pacey, 1999 and Walters, 1995).

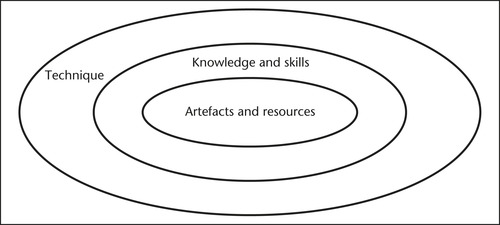

One way to interpret and portray technology is as three concentric circles (see Fig 15.1). Concentric circles highlight the characteristics of technology, and together they therefore emphasise a character-ological interpretation of the phenomenon. The interpretation is useful because it focuses our attention on not only the ‘things we use in nursing and society’ (at the centre), but also their relations with other characteristics that are integral to meaning.

|

| Figure 15.1 |

Artefacts and resources

The smallest and central concentric circle depicted in Figure 15.1, artefacts and resources, is technology at its most obvious and refers to the integration, use and application of the ‘things’ of nursing. Rinard (1996) noted that in modern nursing there have been three key periods of change that have been significantly influenced by technology. The first period was 1950–65 and was characterised by new medical techniques and a significant introduction of pharmaceuticals to care. The second period was 1965–80 and was associated with increasing machinery and specialisation. The third period was from 1980–90 and was associated with increasing technical control, streamlining and prediction of care. A more recent period has not been identified by Rinard, but it could be argued that current nursing is within a period of informational retrieval and computerisation.

We are required to use and maintain increasing amounts of technology in daily practice, and it is useful to clarify the various types of technology that are often found in our practice. We use simple, sophisticated, old, new, unique and commonplace technologies that continue to evolve in design and application. It can be observed that there are at least 12 different types of technologies that are artefacts and resources of nursing. These include clothes (e.g. shroud, pyjamas), utensils (e.g. bedpan, kidney dish), structures (e.g. hospital ward, isolation room), apparatus (e.g. Jordan frame, wheelchair, trolley), utilities (e.g. electricity, gas), tools (e.g. urinary catheter, syringe), resources (e.g. pharmaceuticals, sterile dressing), machines (e.g. intravenous infusion pump), automata (e.g. computer, refrigerator), tools of doing used to enact clinical practice (e.g. nurse’s watch, stethoscope), objects of art or religion (e.g. nurse’s uniform), and toys/games used for diversion (e.g. chessboard).

Although some machinery, apparatus, tools and so on are new, increasingly accurate and powered by utilities such as electricity, it is worth noting that there is also a lot of simple technology that remains fundamental to daily care (e.g. a shower chair, a stethoscope and a bedpan). Artefacts and resources assist to enact complex assessment and treatment, while supporting us to meet the daily needs of each patient. They can manifest as things to be held in our hand, pharmaceuticals we dispense to patients, volumetric pumps we use to assist enteral feeding, and occasionally as various noises and visual stimuli that we observe, such as colour screens and digital displays.

While an extended debate could be undertaken to examine what constitutes technology that is specific to nursing, for the purposes of this chapter nursing technologies include any technology that we use and/or claim to be fundamental to our daily practice. However, in stating this, it must be recognised that a lot of commonplace and simple nursing technology is not acknowledged as significant (e.g. bedpan) (Barnard & Locsin 2007). That is, it lacks recognition as technology by nurses both in clinical practice and in nursing literature. The reasons for the lack of acknowledgment are speculative, but include our emphasis on the application of sophisticated technology, our inclination to uncritically embrace new technologies, a de-emphasis on technology associated with the ‘dirty work’ of nurses, limited investigation into the historical development of nursing technologies and a lack of substantive scholarship examining the phenomenon (Sandelowski 2000).

Knowledge and skills

The second or middle concentric circle in Figure 15.1 portrays technology as knowledge and skills. Artefacts and resources have associated meaning(s) and these are in many ways determined by the knowledge and skills associated with the way we use, repair, design and interpret them. Knowledge and skills contribute to the successful use of artefacts and resources, and are as much technology as the objects themselves. Without required knowledge and skills for the use and application of technology, it has limited ability to meet the needs of nursing practice and care. For example, without the skills necessary to use a computer, it is not much more than plastic, metal and electricity, and will not assist daily practice.

Nursing is a practical occupation and our knowledge is expressed most often through the way we perform our work. We focus often on what we do as practitioners and explain technology from perspectives that emphasise daily roles and responsibilities. For example, there has been debate concerning the increasing role of nurses in the use and maintenance of machinery and equipment. It has been argued that nurses have to fulfil the role of technician, and this is significantly distracting us from focusing on the experience of each patient (Boykin & Schoenhofer 2001).

Nurses rely on experience, continuing education, personal development and peer mentors to maintain and develop knowledge and skills that are associated with technology. Failure to establish and develop knowledge and skills is inadequate for practice and unhelpful to patient care, colleagues and the requirements of the healthcare sector. Knowledge takes many forms and relates to not only competencies related to nursing intervention, but also organisational policy, current research and changing evidence. These all form part of the development of technological competence, which is central to technology–nurse–patient relations and is vitally important for care.

The outcome of technological competence is not only the development of skills for technology use, but also to know ‘the other’ (i.e. the person whom you nurse) in terms related to who they are as individuals. Thus in integrating technology in care we must seek to know their preferences, culture and beliefs. This significant part of caring for another is achieved as an outcome of purposefully seeking to know the other and through making appropriate use of technological data and resources for their benefit (Locsin 2001). One of the most important behaviours that patients look for from nurses is our competence when using technology. Demonstrating competence reduces anxiety and fear and increases the likelihood of successful care outcomes. Advances in organ transplantation, genetics, pharmaceuticals, microsurgery, virtual reality, e-health, telehealth, and so on, demand the ability to update and adapt knowledge, while maintaining technological competence as an essential element of quality care.

Knowledge and skills alter regularly, and thus an active interest in maintaining and advancing competence is a sign of a caring and responsible practitioner who is accountable for the quality of their practice. Attitudes that reflect an offhand and neglectful interest in updating knowledge and skills are inadequate, and reflect a failure to value the importance of the person. It is a denial of the many possible contrary indicated outcomes that might arise from inadequate technology integration and is unprofessional.

Technology introduces options for care and can make clinical practice more efficient, quicker and more accurate. Skills alter as a result of technology, and this fact should encourage personal reflection on the nature, relevance and impact of change on individual and collective practice (Locsin 2001). For example, an automatic blood pressure monitor de-emphasises manual skills related to assessing a person’s blood pressure, but demands new skills in terms of integrating electronic data. Many skills that were required previously for nursing are no longer necessary for contemporary practice and new skills emerge regularly to become part of daily care. For example, the practice many years ago of boiling urine in a test tube to analyse urine was replaced by the use of a coloured test strip, and the electronic blood pressure monitor often replaces the use of a hand-operated sphygmomanometer. We are engaged in an ongoing and regular process of deskilling and reskilling in practice.

The outcomes of technological change are associated with changing technical complexity that should be integrated into the organisation of work. Technological sophistication is always about achieving greater efficiency and logical order, and technological change should be associated with better use of your time and resources and better patient care. For example, the intravenous infusion pump permits nurses to undertake ‘other duties’ while intravenous therapy is being delivered to their patient at a determined rate. However, the intravenous infusion pump de-emphasises skills associated with manually determining flow rate. An infusion pump is often a good thing for time saving and control in daily practice, but at a higher level we are reminded that an often unasked question in relation to technology and nursing is ‘what skills need to be retained’ and ‘what skills can fall away’ as a result of specific technological change(s).

These are important questions and are fundamentally necessary for current and future professional development. For example, although we have been proactive in acquiring new skills and knowledge for care, we are required sometimes to revisit older, less common ways of undertaking certain assessment(s) and treatment(s), especially in less resourced clinical areas.

But amidst all this change, some nurses interpret the process as skills loss, especially when skills associated with caring and human relationships are devalued or ignored. Rinard (1996) postulated that the evolution of technology and nursing is a story of deskilling in which nurses have purposefully gendered nursing knowledge in line with vocational and societal expectations of what is (was) valued culturally as ‘feminine’, at the cost of serious analysis of skills.

Deskilling and reskilling are issues worthy of analysis, but little has been undertaken within the profession. In fact, over the past 60 years nursing has seemingly been reluctant to critically analyse technological change within the contexts of skills alteration, societal trends and the changing nature of nursing work (Barnard, 2002, Barnard and Cushing, 2001, Fairman, 1998, Rinard, 1996 and Sandelowski, 2000). Although new clinical activities have been added to the professional role of the nurse, these additions have been regarded as secondary to a more generalised growth in the sophistication of nursing work.

Most technological development in nursing has arisen as a result of technology replacing older procedures with newer more efficient and reliable technology, and among this there are significant changes occurring to nursing labour. We do things more quickly, more efficiently, with more automation and at times with more accuracy, yet there is a clear disjunction between the social–scientific nature of nursing work, analysis of changing healthcare, theoretical interpretation of nursing and the realities of nursing work. The effects of technological change on the skill of each nurse have been analysed poorly by nurses, but at a practical level changes are linked to increasing technical complexity and alteration to practitioner discretion/autonomy.

Technique

The influence of technology on practitioner discretion/autonomy is most obviously illustrated in the third and most inclusive concentric circle in Figure 15.1, which highlights the concept of technique. The third circle extends our character-ology of technology to include the way systems, policy, politics, economics, ethics, organisational management and human behaviour are organised for the benefit of technology. The way nursing practice is organised for, as well as by, artefacts and resources is as much technology as the first and second levels of meaning. Technique is not an entity or a specific thing. It is a way of thinking, and is an attitude that has an enormous influence upon us and society.

A transformation is occurring in which many aspects of our practice that were once instinctive, reflexive, natural and particular to individuals and cultures are being transformed into rational method and instruction. In craft-based technology the worker is able to express themselves with a sense of creativity, pride in personal agency and autonomy in determining action and expression. In automated technology environments these values and experiences have a tendency to be replaced by a sense of dependency on predetermined actions and protocols, a partial exercise of personal ability and preference, and knowledge that personal input can be replaced by another (Ferre 1995).

Technique is a mentality, a discourse and an objectification of naturally occurring phenomena such as reflective thinking, communication and human behaviour. An example to illustrate technique might be the difference between a caring moment with a patient motivated by nothing more than a nurse’s compassion for another, versus the preplanned use of efficient communication strategies for the fulfilment of predefined goals and outcomes. The latter has all the hallmarks of technique because there is emphasis, for example, on a ‘one best way’ to efficiently undertake the activity. According to Lovekin (1991), technique is the consciousness that gives machines force, that sees everything else as machine-like or as needing to serve the machine-like, the ideal towards which technique strives.

Technique reduces the means of production, whether they be machines or nurses, to that which is most technological (i.e. efficient and rational), in order to create a unified activity. Examples of technique in the management of healthcare services are economic rationalism, protocols, risk assessment, action planning, communication strategies, benchmarking, patient dependency models, systems theory, clinical pathways management and standardised care plans.

Technique is a complex phenomenon that is constituted by three subtle yet important characteristics. First, technique adheres to a primacy of reason to govern practice. It is a way of thinking, acting and living by which people attempt to control the internal, passionate and emotional world of everyday life via protocols, rules, evidence and general observance to a logical order. Second, it requires a desire for efficiency in order to assist its goal and to justify its activity. The desire for efficiency is akin to the inventor or factory owner who seeks to streamline methods and actions in order to obtain certain outcomes. Efficiency seeks practical utility and a guaranteeing of results. There is a striving to reduce waste and the construction of systems that simplify and systematise previously uncontrolled or random activity. We nurses are free to engage in clinical practice, but this freedom is limited much like that of a clock. There is freedom for the hands to move around the clock face as long as nothing ‘gets in the way’. The gears and springs move freely within the mechanism, yet there is a clear expectation that behaviour is determined and replicable.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access