Section Fifteen Neurologic Procedures

PROCEDURE 90 Positioning the Patient with Increased Intracranial Pressure

PROCEDURE 92 Intracranial Pressure Monitoring

PROCEDURE 90 Positioning the Patient with Increased Intracranial Pressure

OVERVIEW

Positioning the patient properly is important to minimize increased intracranial pressure (ICP) in the presence of a head injury, brain lesion, stroke, or other neurologic disorder. Normal ICP is 0 to 10 mm Hg. ICP above 15 mm Hg is elevated; a level above 20 mm Hg is considered intracranial hypertension; and levels above 25 mm Hg should be avoided. Proper positioning facilitates cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and venous drainage from the head via jugular veins and the vertebral venous plexi, thus reducing ICP (Fan, 2004; McLeod, 2004; Price, Collins, & Gallagher, 2003).

Head elevation reduces ICP; however, this practice has been challenged. Some investigators argue that although head elevation lowers ICP, it also contributes to decreased cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP); others rationalize that a horizontal position increases cerebral blood flow (CBF) (Fan, 2004). Data suggest a moderate approach of head elevation between 15 and 30 degrees reduces ICP significantly without impairing CPP (Fan, 2004). Adequate blood flow to the brain is dependent on the CPP, which is the difference between the systemic mean arterial pressure (MAP) and the ICP: CPP = MAP − ICP. Normal MAP levels range from 80 to 100 mm Hg. Autoregulation keeps the cerebral blood flow stable when CPP is between 50 and 150 mm Hg. When CPP decreases, autoregulation may be lost and cerebral blood flow will decrease. In the presence of a traumatic brain injury, a CPP of 50-70 mm Hg is recommended for adult patients (Brain Trauma Foundation, 2007). Elevating the head of the bed more than 40 degrees may contribute to postural hypotension and decreased cerebral perfusion (McLeod, 2004).

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND CAUTIONS

1. Avoid the prone and Trendelenburg positions. Some controversy exists as to whether the patient should be placed in a flat position, and ICP monitoring may be indicated. Types of monitoring devices available may include bolts or screws, cannulas, and fiberoptic probes) (see Procedure 92).

2. Head elevation is commonly used to reduce ICP; however, research has challenged this practice. Although head elevation lowers ICP, it also contributes to decreased CPP; a horizontal position increases CPP. A moderate approach of head elevation between 15 and 30 degrees can reduce ICP significantly without impairing CPP. Consult with the physician to determine if head elevation is indicated.

3. When head elevation must be interupted, restore it promptly—that is, during transport after computed tomography (CT) scan or after endotracheal intubation (two common reasons the patient may be flat for a procedure).

4. Elevating the head of the bed more than 40 degrees may contribute to postural hypotension and decreased cerebral perfusion.

5. Minimize noxious stimuli. Warn the patient before you touch him or her, explain the procedures, and use gentle movements. Do not jar the bed, make loud noises, or use bright lights.

6. Plan turning or positioning activities separately from other nursing interventions. Allow at least 15 minutes between each activity to avoid a cumulative effect of ICP increases.

7. Head elevation is contraindicated in hypotensive patients because it further compromises CPP.

8. Spinal alignment should be maintained until the patient’s spine has been cleared of fracture per institutional protocol.

9. Plan for cervical CT scan when brain CT is being done. Prompt clearance of the cervical spine permits earlier removal of boards and collars, which impede access and cause skin pressure problems.

PATIENT PREPARATION

1. Place the patient in a supine position.

2. Maintain the head in a neutral position without flexion, extension, or rotation.

3. The patient’s head should remain in a neutral position without rotation to the left or right, flexion, or extension of the neck.

PROCEDURAL STEPS

1. Place the bed or stretcher in the prescribed position.

2. Align the torso and the lower extremities. Extreme hip flexion may increase intraabdominal pressure, which can also increase ICP. Legs should be flexed no more than 90 degrees at the hip.

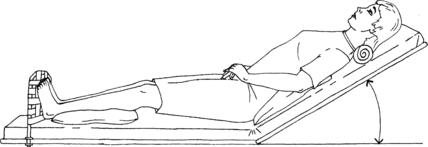

3. A padded footboard at the end of the stretcher or bed can prevent the patient from sliding or shifting positions when the head of the bed is elevated (Figure 90-1).

4. Padded side rails may be needed for seizure precautions.

5. Reposition the patient every 2 hours. Logroll the patient while maintaining head and neck alignment. Ensure the legs are flexed no more than 90 degrees at the hip while the patient is side-lying. Movement of the patient should be slow and purposeful (Kerr and Crago, 2004).

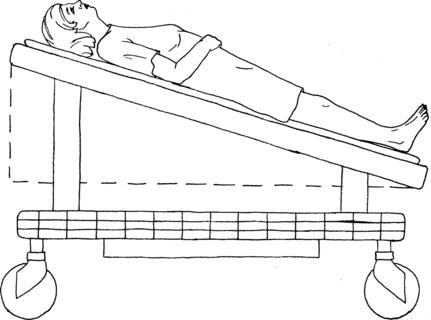

6. If the patient must remain on a backboard or cannot flex at the hips, use a reverse Trendelenburg position at a 15-degree angle to elevate the patient’s head (Figure 90-2). Make sure the board cannot slide off the foot of the stretcher or bed. Backboards are rescue and transport devices not suited for long-term care. Earliest possible safe removal is necessary and should have priority in planning care.

AGE-SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS

Pediatrics

1. Children are predisposed to head trauma because their head-to-body ratio is greater, their brains are less myelinated, and their cranial bones are thinner than in adults (Brain Trauma Foundation, 2003). Emergency personnel must be aware of the potential for intracranial complications when assessing and managing children with head trauma.

2. The use of restraints and immobilization devices to maintain body position may compound the patient’s agitation and lead to increased ICP, especially in young children.

3. If using the Glasgow Coma Scale for neurologic assessment of children under the age of 2 years, a full verbal score can be assigned if the child cries after stimulation (Brain Trauma Foundation, 2003).

4. A CPP of 40 mm Hg or higher is recommended in children with traumatic brain injury (Brain Trauma Foundation, 2003).

Geriatrics

1. Age-related physiologic changes result in a decline in function of all organ systems and may predispose the elderly to trauma.

2. Undertriage has been reported in the literature (Scheetz, 2005). Vital signs, used as a measure of physiologic response to injury, may be altered due to underlying disease or the use of certain medications. Confusion, which is used as a measure of cerebral perfusion, may be mistaken for dementia.

3. Cognitive impairment may be associated with altered function or reduced complaints of pain.

COMPLICATIONS

1. Neck flexion or extension, or rotation of the head to the left or right, increases ICP by obstructing venous outflow.

2. Abnormal posturing may be stimulated by the position of the head in relation to gravity or by excessive noxious stimuli.

3. Pooling of secretions or skin breakdown may occur if the patient is not turned every 2 hours. Consider a nasopharyngeal airway as a protective conduit for pharyngeal suctioning to minimize noxious stimuli. Presence of a basilar skull fracture may alter the airway plan, however.

4. Turn and move the patient gently. Pain or agitation can increase ICP.

PATIENT TEACHING

1. Conscious patients should report increasing headache, nausea, or visual disturbances.

2. Explain that positioning is used along with other interventions to control the intracranial pressure. The position is to be changed every 2 hours.

3. Family members should be advised not to give the patient additional fluids or to change the position of the bed without asking the nurse.

Brain Trauma Foundation. (2000). Management and prognosis of severe traumatic brain injury. Retrieved December 6, 2006, from www2.braintrauma.org/guidelines

Brain Trauma Foundation. (2003). Guidelines for the acute medical management of severe traumatic brain injury in infants, children, and adolescents. Retrieved December 8, 2006, from www2.braintrauma.org/guidelines.

Brain Trauma Foundation. (2007). Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. Retrieved July 26, 2007 from www2.braintrauma.org/guidelines

Fan J. Effect of backrest position on intracranial pressure and cerebral perfusion pressure in individuals with brain injury: A systematic review. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 2004;36(5):278–288.

Kerr M., Crago E. Acute intracranial problems. In: Lewis S., Heitkemper M., Dirksen S. Medical-surgical nursing: Assessment and management of clinical problems. St Louis: Mosby; 2004:1491–1524.

McLeod A. Traumatic injuries to the head and spine 2: Nursing considerations. British Journal of Nursing. 2004;13(17):1041–1049.

Price A., Collins T., Gallagher A. Nursing care of the acute head injury: A review of the evidence. Nursing in Critical Care. 2003;8(3):126–133.

Scheetz L. Relationship of age, injury severity, injury type, comorbid conditions, level of care, and survival among older motor vehicle trauma patients. Research in Nursing & Health. 2005;28:198–209.

PROCEDURE 91 Lumbar Puncture

Lumbar puncture is also known as LP, spinal tap, or spinal puncture.

INDICATIONS

1. To assist in the diagnosis of meningitis or encephalitis in febrile patients exhibiting an acute alteration in mental status.

2. As part of fever work-up in a febrile infant less than 3 months old without any obvious source of infection.

3. To assist in the diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). If SAH is highly suspected and computed tomography (CT) of the head results are negative, LP may be required for diagnosis.

4. To instill medication, blood, or radiopaque contrast material into the subarachnoid space for the diagnosis or treatment of central nervous system (CNS) disorders.

5. To measure cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure.

6. To assist with the diagnosis acute or chronic demyelinating diseases (e.g., Guillain-Barré, multiple sclerosis, transverse myelitis), malignancies (e.g., meningeal carcinomatosis), or unexplained neurologic disorders when the CT scan is negative (e.g., altered level of consciouness, polyneuropathy) (German & O’Brien, 2003).

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND CAUTIONS

1. If a LP is performed in the presence of elevated intracranial pressure, supratentorial or foramen magnum herniation may occur due to changes in the pressure gradient between the supratentorial and lumbar spaces when CSF is removed. Herniation may lead to serious injury or death. A computed tomography (CT) scan should precede the LP in a patient with a history of a progressive deterioration of mental status, a worsening headache, localizing neurologic signs, or papilledema (Euerle, 2004).

2. Positioning patients with excessive neck flexion may cause respiratory compromise. The risk is higher in sedated patients and children (due to their increased neck flexibility and shorter, narrower airways). In these populations, monitor respiratory status with pulse oximetry and/or end-tidal CO2 (see Procedures 21 and 24). End-tidal CO2 via side-stream capnography will provide earlier warning of hypoventilation or airway compromise than pulse oximetry.

3. Performing a LP in an anticoagulated or thrombocytopenic patient may result in a spinal epidural hematoma.

4. A superficial infection at the puncture site could cause meningitis or an epidural or subdural empyema. LP through infected tissue is contraindicated.

EQUIPMENT

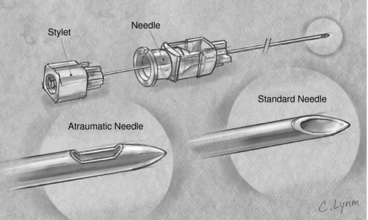

21- to 25-G, 2.5- to 3-in spinal needle with stylet (longer needles may be necessary for obese patients). Atraumatic spinal needles are preferred (see Figure 91-1)

25-G, ⅝-in needle and 21- or 22-G, ½- and 1-in needles for anesthetic infiltration

Manometer with three-way stopcock (extension tubing optional)

(Preassembled kits containing all or some of these supplies are available.)

PATIENT PREPARATION

1. Obtain a blood glucose level to rule out symptomatic hypoglycemia (neuroglycopenia) and as a baseline to compare with CSF glucose level.

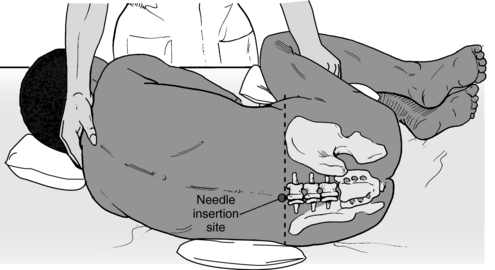

2. Assist the patient into a lateral decubitus position, with the shoulders and pelvis perpendicular to the stretcher. The patient should flex or curl the back and maintain this position to separate the lumbar spine segments (Figure 91-2). It may help to provide a small pillow for the head. Infants, children, and uncooperative adults may require assistance to maintain this position.

3. If the patient has bony deformities or is obese, a sitting position with head and arms resting over a padded bedside table may help to identify landmarks. This position can be maintained during the LP. The initial opening pressure measurement is not valid in the sitting position due to the vertical column of CSF in the spinal canal. Patients with bony deformities may need fluoroscopic guidance for the puncture.

4. When time allows, a topical anesthetic, such as EMLA, may be used over the insertion site and the next lower level as an alternate site (see Procedure 135).

PROCEDURAL STEPS

1. * Palpate the back to identify the spinous process levels. The levels of L3-4, L4-5, or L5-S1 can be used safely, because they avoid the spinal cord, which ends at the level of L2-3. The posterior iliac crest is even with L3-4. The site may be marked with an indentation from a fingernail or a skin marker.

2. *Cleanse the back in a circular fashion with an antiseptic solution.

3. *Attach the sterile drape to the patient’s back with the adhesive strips.

4. *Infiltrate the skin and the subcutaneous tissue with the anesthetic solution via the 25-gauge needle. Infiltrate the interspinous spaces with the anesthetic solution at the intended puncture site via the 22-gauge needle.

5. *Identify the intended puncture site and insert the spinal needle at the midline with the bevel parallel to the axis of the spine. The needle is often angled slightly cephalad. The patient will feel pressure but should not feel pain.

6. *A pop may be felt once the needle passes the ligamentum flavum, and it is advisable at this point to remove the stylet and to check for the CSF every 2 mm or so to avoid passing through the subarachnoid space into the ventral epidural space. If the epidural space is entered, the patient may feel pain from the puncture of a nerve root or there may be bleeding from puncture of the plexus of veins that forms a ring around the spinal cord. This is termed a traumatic tap, but it is not a patricularly dangerous problem in a patient with normal coagulation (Euerle, 2004).

7. *Once CSF is noted at the hub of the needle, attach the manometer and the three-way stopcock to measure CSF opening pressure. Extension tubing may be used between the needle and the manometer to allow greater flexibility, but the manometer should be placed so that the zero mark is at the level of the hub of the spinal needle. The patient should be asked to relax and may extend the legs as this does not meaningfully affect the opening pressure reading (Euerle, 2004). Have the patient breathe quietly, and read the pressure when it comes to a rest and fluctuates only slightly with each breath. Normal CSF pressure is 50 to 200 mm H2O (German & O’Brien, 2003).

8. *Collect CSF specimens in the four collection tubes. Fluid from the manometer may be drained into the first tube. Usually, 1 to 2 ml is placed in each tube. Each institution determines which tests will be performed on the different tubes. Generally, if the fluid in the first tube is bloody, it is discarded or held. Cell counts with differential, protein, and glucose are done on tube 2 or 3. Gram stain with culture and sensitivity is done on tube 3 or 4 in order to lessen the chance of skin contamination. Viral testing, cytology or other specialized studies may be done on tube 4 as indicated. If a traumatic tap is suspected, a comparison cell count may also be done on tube 4. The CSF specimens should be transported to the laboratory promptly to prevent cell lysis, which may cause false results (Chernecky & Berger, 2004).

Normal CSF findings include the following (German & O’Brien, 2003):

9. * Reinsert the stylet and slowly remove the spinal needle. Apply pressure to the site with a gauze pad, and then apply the adhesive gauze pad.

10. The patient should remain flat for at least 2 hours. Prone positioning may help reduce CSF leakage and thereby decrease the likelihood of post-LP headache.

11. Observe the patient for any changes in the level of consciousness (in case of worsening meningitis or possible herniation), altered motor or sensory status in the lower extremities, bladder dysfunction (spinal subdural hematoma), or complaints of headache.

Table 91-1 Basic Differentiation of Cerebrospinal Fluid Findings in Viral and Bacterial Meningitis

| Viral | Bacterial | |

|---|---|---|

| WBC | Elevated, lymphocytes predominant | Very high, neutrophils predominant |

| Protein | Normal-to-mild increase | High |

| Glucose | Usually normal | Low, less than 60% of serum glucose |

WBC, White blood cell.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree