Care of Patients with Disorders of the Upper Respiratory System

Objectives

1. Recognize symptoms of disorders of the sinuses, pharynx, and larynx.

2. Describe the postoperative care for the patient undergoing a rhinoplasty.

3. List emergency measures for the patient with an airway obstruction.

4. Review a nursing care plan for the patient who had a laryngectomy.

5. Analyze safety factors to be considered when caring for the patient with a tracheostomy.

1. Institute measures to stop epistaxis.

3. Devise interventions for the psychosocial care of the patient who has undergone a laryngectomy.

Key Terms

crepitation (KRĔP-ĭ-tā-shŭn, p. 283)

endotracheal intubation (ĔN-dō-TRĀ-kē-ăl ĭn-tyū-bā-shŭn, p. 284)

epistaxis (ĕp-ĭ-STĂK-sĭs, p. 280)

follicular pharyngitis (fōl-ĭk-yĕ-lĕr fĕr-ĭn-jī-tĭs, p. 280)

laryngectomy (lăr-ĭn-JĔK-tō-mē, p. 283)

laryngitis (lăr-ĭn-JĪ-tĭs, p. 280)

laryngoscope (lăr-ĭn-JĔ-skōp, p. 284)

lozenges (p. 280)

obturator (ŎB-tŭ-ră-tŏr, p. 285)

pharyngitis (fĕr-ĭn jī-tĭs, p. 280)

rhinitis (rī-NĪ-tĭs, p. 277)

rhinoplasty (RĪ-nō-plăs-tē, p. 283)

stoma (STŌ-mă, p. 283)

tracheostomy (trā-kē-ŎS-tō-mē, p. 284)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

Disorders of the Nose and Sinuses

Upper Respiratory Infection (URI) (the Common Cold) and Rhinitis

The common cold—acute viral rhinitis—is an inflammation of the nose and upper respiratory tract. It is the most prevalent infectious disease among people of all ages. Many different strains of viruses can produce the symptoms of a common cold, thus total immunity is unlikely. Avoiding exposure to those who have a cold and maintaining a state of good health are the only ways one can avoid “catching” a cold.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Viruses are spread by airborne droplet sprays from infected people during breathing, speaking, coughing, or sneezing, or by direct hand contact with a contaminated object. A chill, fatigue, physical or emotional stress, a compromised immune status or inflammation caused by allergic rhinitis makes one more susceptible to contracting an upper respiratory virus.

Signs, Symptoms, and Diagnosis

The common cold usually starts with a mild sore throat or a hot, dry, prickly sensation in the nose and back of the throat. Within hours after the onset of a cold, the nose becomes congested with increased secretions, the eyes begin to water, and sneezing, malaise, and an irritating, nonproductive cough appear. The invading organism causes inflammation and swelling of the mucosa. Muscle aches and headache may occur. There usually is no elevation of temperature; if a fever does develop, it is low grade (<101° F [38.3° C]). In most instances, a cold will last 10 to 14 days before all symptoms are gone.

Allergic rhinitis may have many of the symptoms of a cold, except there is no fever. It is caused by reaction of the nasal mucosa to an allergen, such as pollen or dust.

Treatment and Nursing Management

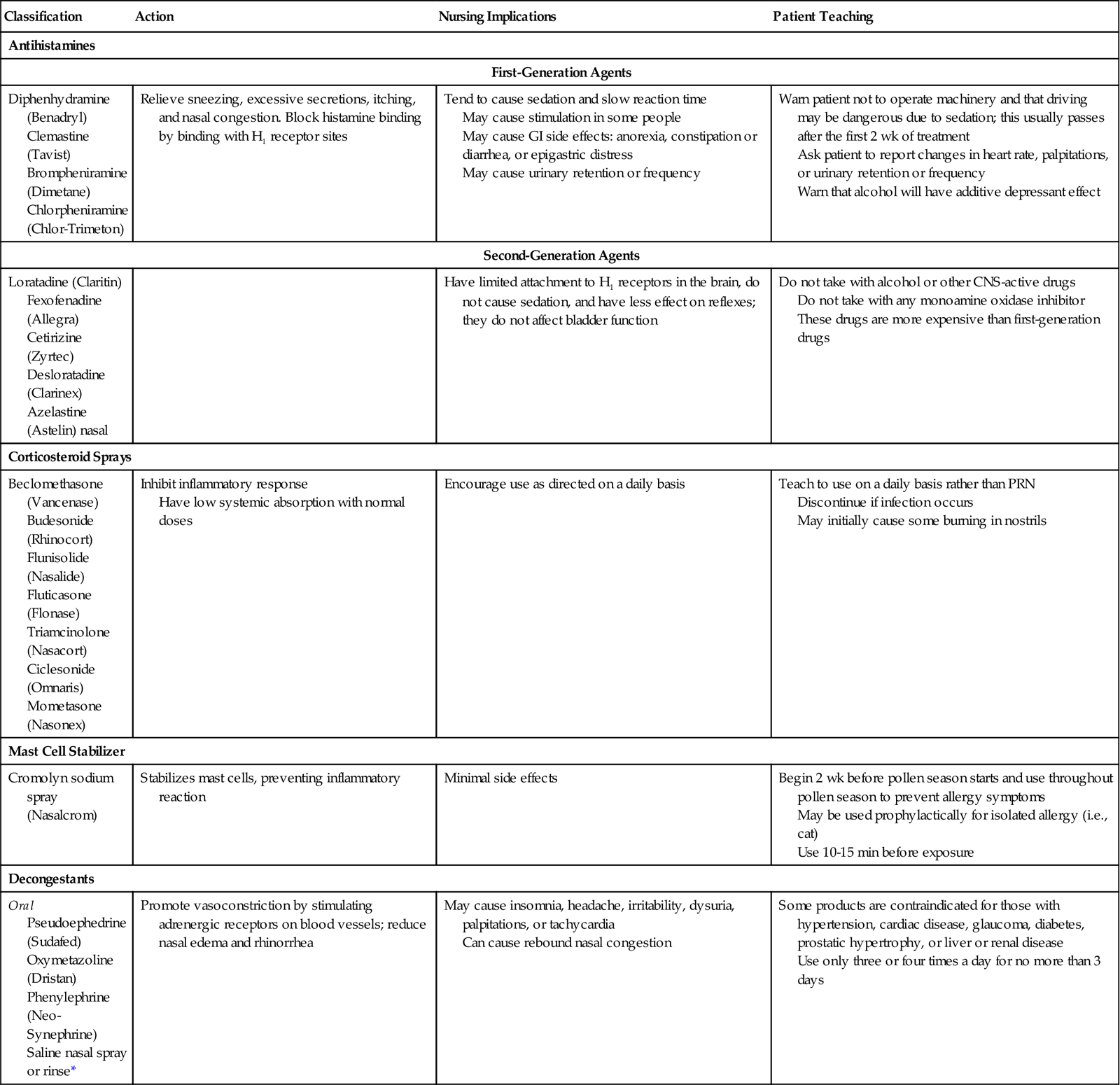

The treatment of allergic rhinitis is symptomatic. Antihistamines, steroids, and sprays that stabilize the mucous cell membranes are often prescribed (Table 14-1). The patient is taught to avoid the offending allergens as much as possible. If the disorder is severe, an allergy evaluation is indicated so that a desensitization program can be started.

Table 14-1

Commonly Prescribed Drugs for Allergic Rhinitis and Sinusitis

| Classification | Action | Nursing Implications | Patient Teaching |

| Antihistamines | |||

| First-Generation Agents | |||

| Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) Clemastine (Tavist) Brompheniramine (Dimetane) Chlorpheniramine (Chlor-Trimeton) | Relieve sneezing, excessive secretions, itching, and nasal congestion. Block histamine binding by binding with H1 receptor sites | Tend to cause sedation and slow reaction time May cause stimulation in some people May cause GI side effects: anorexia, constipation or diarrhea, or epigastric distress May cause urinary retention or frequency | Warn patient not to operate machinery and that driving may be dangerous due to sedation; this usually passes after the first 2 wk of treatment Ask patient to report changes in heart rate, palpitations, or urinary retention or frequency Warn that alcohol will have additive depressant effect |

| Second-Generation Agents | |||

| Loratadine (Claritin) Fexofenadine (Allegra) Cetirizine (Zyrtec) Desloratadine (Clarinex) Azelastine (Astelin) nasal | Have limited attachment to H1 receptors in the brain, do not cause sedation, and have less effect on reflexes; they do not affect bladder function | Do not take with alcohol or other CNS-active drugs Do not take with any monoamine oxidase inhibitor These drugs are more expensive than first-generation drugs | |

| Corticosteroid Sprays | |||

| Beclomethasone (Vancenase) Budesonide (Rhinocort) Flunisolide (Nasalide) Fluticasone (Flonase) Triamcinolone (Nasacort) Ciclesonide (Omnaris) Mometasone (Nasonex) | Inhibit inflammatory response Have low systemic absorption with normal doses | Encourage use as directed on a daily basis | Teach to use on a daily basis rather than PRN Discontinue if infection occurs May initially cause some burning in nostrils |

| Mast Cell Stabilizer | |||

| Cromolyn sodium spray (Nasalcrom) | Stabilizes mast cells, preventing inflammatory reaction | Minimal side effects | Begin 2 wk before pollen season starts and use throughout pollen season to prevent allergy symptoms May be used prophylactically for isolated allergy (i.e., cat) Use 10-15 min before exposure |

| Decongestants | |||

| Oral Pseudoephedrine (Sudafed) Oxymetazoline (Dristan) Phenylephrine (Neo-Synephrine) Saline nasal spray or rinse* | Promote vasoconstriction by stimulating adrenergic receptors on blood vessels; reduce nasal edema and rhinorrhea | May cause insomnia, headache, irritability, dysuria, palpitations, or tachycardia Can cause rebound nasal congestion | Some products are contraindicated for those with hypertension, cardiac disease, glaucoma, diabetes, prostatic hypertrophy, or liver or renal disease Use only three or four times a day for no more than 3 days |

CNS, central nervous system; GI, gastrointestinal; H1, histamine-1; PRN, as needed.

*Saline nasal sprays and rinses wash away pollen and dust, thin secretions, and soothe the nasal mucosa.

There is no cure for the common cold. However, zinc lozenges have proven effective in limiting a cold’s duration and severity for many people, if started at the first signs of symptoms (Prasad et al., 2008).

A major goal in the care of a common cold is prevention of a secondary bacterial infection. Individuals with a cold should avoid contact with others so as to avoid picking up a bacterial infection or giving their viral infection to someone else. A person with a cold is contagious for about 3 days after symptoms first appear.

Colds are spread by droplet infection and most people realize that coughing and sneezing will spread viruses. Coughing and sneezing into tissues does limit the viruses’ travel by air, but the viruses are also very likely to be on the person’s hands, where they can be transferred to anything touched. Hand hygiene is important in the prevention of spreading infection to others and patients should also be taught not to share personal use items, such as drinking glasses.

The patient should stay indoors, preferably in bed or resting, during the first few days of the illness. Fluid intake should be increased. Fruit juices are recommended, especially citrus juices, because of their vitamin C content. Aspirin or another mild nonprescription analgesic can help relieve the muscle aches and headache of a cold.

Decongestant nose drops or sprays such as oxymetazoline (for the relief of nasal congestion) can have a rebound effect, leaving the nose “stuffier” if used for more than 3 days. Frequent use of saline nasal spray decreases congestion without side effects. Antibiotics are not given because a cold is a viral infection.

A bacterial infection, which requires medical treatment, is present when a “cold” persists for more than a week to 10 days without improvement, or if the patient begins to feel worse, has a temperature of 101° F(38.3° C), and develops chest pains or coughs up purulent sputum.

Sinusitis

Sinusitis is an inflammation of the mucosal lining of the sinuses. Pneumococci, streptococci, or Haemophilus influenzae are the usual pathogens and infection can spread from the nasal passages to the sinuses. The nasal passages can be blocked by a deviated septum which may occur congenitally, or from injury to the nose, or by nasal polyps. Polyps occur from repeated inflammation of the nasal mucosa and are tissue growths that obstruct airflow. Sinusitis often occurs after colds or other respiratory infections and during periods of uncontrolled allergic rhinitis. People with a deviated nasal septum or allergy problems tend to have recurrent sinusitis.

As exudate accumulates in the sinuses, pressure builds up causing pain. Symptoms include headache, fever, tenderness over the sinuses, malaise, purulent drainage from the nose, and sometimes a nonproductive cough. The upper teeth may become painful.

Treatment of sinusitis includes relieving pain, promoting sinus drainage, controlling infection, and preventing recurrence. Hot, moist packs over the sinus area can be helpful. Inhaling moist steam thins secretions and kits for sinus irrigation available at drugstores help to promote drainage. Medications are prescribed to promote decongestion or vasoconstriction and to reduce swelling, to promote drainage and to relieve pain. Infection may be treated with an antibiotic or anti-infective agent, often for at least 10 days. Rest, reduced stress, a balanced diet, and control of allergies can help prevent recurrence. Fluid intake should be increased. Dairy products increase the thickness of secretions, therefore are limited during the illness.

Acute or chronic sinus infection can cause a variety of complications, including septicemia, meningitis, and brain abscess. When sinus infection is chronic, surgery to clean out the sinuses may be necessary. A deviated septum can be surgically repaired, and polyps can be removed by laser treatment.

Epistaxis

Epistaxis (nosebleed) is a common occurrence and usually results from crusting, cracking, or irritation of the mucous membrane covering the front of the nasal septum. Blood loss is usually minimal. Decreased humidity, excessive nose blowing, allergy with inflammation, and nose picking may cause nosebleeds. Overuse of nasal spray, street drug use (particularly “snorting”), and tumors are other causes. Any condition that prolongs bleeding time or lowers the platelet count may predispose to nosebleeds. Nosebleeds can also result from trauma, hypertension, and blood disorders such as leukemia. They are common in boys during pubescence.

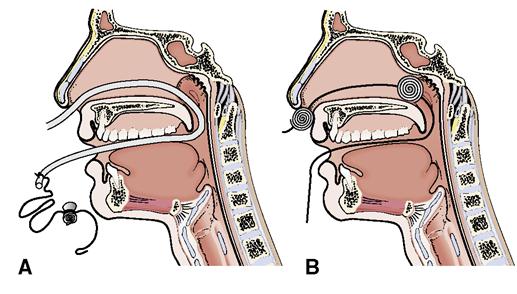

Bleeding from the nose is the only sign of epistaxis. When epistaxis occurs, the patient should sit forward and apply direct pressure by pinching the soft portion of the nose for 10 to 15 minutes. This position prevents blood from running down the back of the throat. Cold compresses or ice may be applied to the nose to constrict the blood vessels. If there is still bleeding at the end of a 10- to 15-minute period, a small gauze pad may be inserted into the bleeding nostril and digital pressure applied (Figure 14-1). If bleeding continues, the patient should go to the emergency department, where a physician will cauterize the bleeding vessels or solidly pack the nose, or insert a small balloon device, to stop the bleeding (Figure 14-2). Once bleeding stops, the patient should rest quietly for a few hours and be warned not to blow the nose, pick at it, or rub it for 24 hours after the nosebleed has stopped.

Pharyngitis

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Pharyngitis (inflammation of the pharynx), usually called a sore throat, may be caused by a virus, bacteria, or a fungus. The majority of cases are viral. Acute follicular pharyngitis (“strep throat”) is caused by beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection. Fungal pharyngitis occurs with long-term use of antibiotics or inhaled corticosteroids, or in patients with immunosuppression, such as occurs with HIV or AIDS or during cancer treatment. Laryngitis (inflammation of the larynx with diminished voice or hoarseness) may occur if the infection progresses into the larynx. If the inflammation extends to the epiglottis, epiglottitis occurs; this is more common in children.

Signs, Symptoms, and Diagnosis

The symptoms include a dry, “scratchy” feeling in the back of the throat, mild fever, headache, and malaise. The throat, tonsils, palate, and uvula may be involved and will be reddened. Dysphagia causes discomfort when swallowing one’s own saliva. With laryngitis, the voice may become hoarse or absent. The usual course for uncomplicated pharyngitis or laryngitis is 3 to 10 days. The diagnosis of pharyngitis is confirmed by clinical signs and symptoms. A throat culture is often done to confirm or rule out streptococcal infection.

Treatment and Nursing Management

Uncomplicated viral pharyngitis usually responds to conservative measures, such as rest, warm saline gargles (½ to 1 tsp of table salt to a glass of warm water), throat lozenges (small medicinal tablets that dissolve in the mouth), antiseptic sprays, plenty of fluids, and a mild analgesic for aches and pains.

Bacterial pharyngitis requires antibiotic therapy, particularly if the infecting organism is Streptococcus. Chronic pharyngitis may require diagnostic procedures to determine the underlying cause, and therapeutic measures such as humidification and filtering of environmental air. Fungal pharyngitis is treated with an antifungal agent, but may be difficult to control in immunocompromised individuals.

Tonsillitis

Etiology and Pathophysiology

An infection with inflammation of the tonsils is usually caused by streptococci, staphylococci, or H. influenzae and is different from pharyngitis; however symptoms may be somewhat similar. Acute tonsillitis may occur repeatedly, especially in those who have a low resistance to infection.

Signs, Symptoms, and Diagnosis

Acute tonsillitis occurs more frequently in young children. There is high fever, sore throat, general malaise, pain referred to the ears, and chills. Inspection of the throat reveals redness and swelling of the tonsils and surrounding tissues with patches of yellow exudate. The white blood cell count becomes elevated.

Chronic tonsillitis usually produces an enlargement of tonsillar tissue and adenoidal tissue. Chronic infection produces less dramatic symptoms than acute tonsillitis but discomfort still occurs. A person with chronic tonsillitis and enlarged adenoids has frequent colds and appears to be in poor health.

Diagnosis is by physical examination and history. If a streptococcus infection is suspected, a throat culture may be performed, or a “rapid strep test” may be done.

Treatment

A throat culture is done before treatment to check for the presence of Streptococcus, which can cause rheumatic fever or glomerulonephritis if not treated promptly. Acute tonsillitis is treated with warm saline throat gargles and the administration of specific antibiotics (usually penicillin) to destroy the pathogen. Nursing measures include bed rest, fever management, and a liquid diet to minimize trauma to the tissues. After 24 hours on antibiotics, the patient is no longer considered contagious (Mayo Clinic, 2009).

Surgery is used to treat tonsillitis when it is recurrent or when enlargement of the tonsils and adenoids obstructs airways. Surgery is considered if the patient has more than seven episodes of tonsillitis per year, after acute infection has cleared.

Nursing Management

Preoperative Care

Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy are generally done on an outpatient, same-day surgery basis. Preliminary laboratory testing and patient education begin before the patient is admitted. Physical preparation of the patient involves administration of preoperative medications as ordered and restriction of the patient’s diet for 6 to 8 hours before surgery. An elevation of temperature or any signs of URI should be reported, because surgery is usually postponed if these signs are present. The patient also has an easier time swallowing postoperatively.

Postoperative Care

Although tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy patients usually recover rapidly and rarely suffer any complications, the nurse is vigilant for signs of hemorrhage. Vital signs are checked frequently, and the patient is observed for frequent swallowing, which may indicate bleeding in the throat. Restlessness can be another clue to excessive bleeding. Sneezing, coughing, and vomiting can cause bleeding. An ice collar may be placed around the neck to reduce swelling and prevent the oozing of blood from the operative site. The patient can be positioned on the side as long as there is drainage from the surgical wound. For comfort, the patient may sit up in a semi-Fowler’s position after recovering from the anesthesia. The postoperative diet usually consists of ice-cold liquids, Popsicles, and gelatin (without red coloring), progressing to ice cream, custards, and other semisolid foods for the first 24 hours. Citrus fruits, hot fluids, and rough foods should be avoided until the throat has completely healed. Straws are not used because sucking may cause bleeding. Written instructions for routine care and emergency circumstances are reviewed with the caregiver and patient.

Obstruction and Trauma

Airway Obstruction and Respiratory Arrest

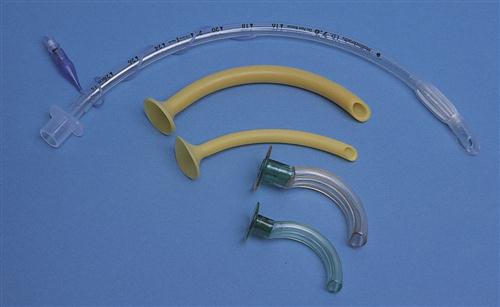

Laryngeal edema from inflammation of an infection or an allergic reaction may obstruct the airway. A crush injury of the larynx may cause airway obstruction. A foreign object or food that goes down the airway rather than the esophagus can cause obstruction. If the person seems to be choking, encourage forceful coughing if possible. If that person cannot breathe or speak, she may make the universal signal for choking, signaling for help by grasping at the throat with the hands (Figure 14-3). If breathing is obstructed, abdominal thrusts (also known as the Heimlich maneuver) should be performed  (American Heart Association, 2009). The arms are wrapped around the victim from behind. One hand makes a fist with the thumb inward, then position the fist just above the umibilicus. The other hand wraps around the fist. Upward thrusts are delivered into the abdomen to try to dislodge anything stuck in the airway (Figure 14-4) (see Chapter 45). In the unconscious adult or child over 1 year of age, the most common cause of airway obstruction is the tongue. An artificial airway may be orally or nasally inserted; it helps to keep the tongue in place (Figure 14-5).

(American Heart Association, 2009). The arms are wrapped around the victim from behind. One hand makes a fist with the thumb inward, then position the fist just above the umibilicus. The other hand wraps around the fist. Upward thrusts are delivered into the abdomen to try to dislodge anything stuck in the airway (Figure 14-4) (see Chapter 45). In the unconscious adult or child over 1 year of age, the most common cause of airway obstruction is the tongue. An artificial airway may be orally or nasally inserted; it helps to keep the tongue in place (Figure 14-5).

If the airway is obstructed for an extended period, the heart may stop due to hypoxia. If the obstruction is cleared, but the victim has no pulse, cardiopulmonary resuscitation must be started (see Chapter 45).

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a condition in which the person stops breathing during sleep for 10 seconds or more, until there is a reflex gasp for air. Muscle relaxation at the back of the throat is the most common cause. Snoring is frequent with this condition and sleeping partners are usually the first to notice the problem. A sleep study should be performed to determine the specific type of disorder. Sleep apnea is treated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) applied with a mask or nasal prongs. Untreated sleep apnea can contribute to myocardial infarction or stroke. It also causes constant fatigue. Research is being conducted on the use of capnography to monitor and identify patients with OSA. Capnography measures exhaled carbon dioxide, apneic events, and respiratory rates.

Nasal Fracture

Nasal fracture often results from sports injuries, motor vehicle accidents, or physical assault. If the cartilage or bone is not displaced, complications are unlikely and no treatment is needed. Displacement of the cartilage or bone can interfere with airflow, cause deformity of the nose, and become a potential spot for infection.

Diagnosis is by visual inspection for deformity, a change in nasal breathing, and presence of crepitation (grating sound or feeling of rough surfaces rubbing together) on palpation. If the patient is seen within the first 24 hours after injury, a closed reduction is most often performed using local or general anesthetic. Treatment includes pain relief and the use of ice or cold compresses to reduce swelling.

If the fracture is severe, rhinoplasty (surgical reconstruction of the nose) may be done to improve airflow and cosmetic appearance. After surgery, the patient will have packing in both nostrils and a small plaster splint or cast to provide support. A drip pad of folded gauze is secured as a “mustache” dressing beneath the nose.

The patient is observed for frequent swallowing postoperatively, which could indicate posterior nasal bleeding. Vital signs are monitored closely, and the amount of drainage on the dressing is observed. The patient should be encouraged to rest in a semi-Fowler’s position. Cool compresses are used to decrease nose and facial swelling. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin are to be avoided as they may cause bleeding to occur in the early postoperative period. Forceful coughing and straining at stool (Valsalva maneuver) are to be avoided. A humidifier is used to decrease mucosal drying. After recovery from anesthesia, the patient is usually discharged to recuperate at home. It may take 6 to 12 months before the final result of the surgery is evident.

Cosmetic rhinoplasty is often performed on noses to improve physical appearance. Care is the same as for the procedure for a fractured nose.

Cancer of the Larynx

Etiology and Pathophysiology

It was predicted that there would be 15,000 new cases of cancer of the larynx in 2011 (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2011). Approximately 90% of all patients who are diagnosed early and treated with radiation and/or surgery are cured. Although the cause of cancer of the larynx is unknown, there is some evidence that predisposing factors include cigarette smoking, alcohol abuse, diets rich in spicy foods, infection with human papillomavirus, chronic laryngitis, abuse of the vocal cords, exposure to radiation, and a familial tendency to cancer. Exposures over long periods to environmental pollutants, such as asbestos, paint fumes, or wood dust, are other risk factors (ACS, 2009c). The most common malignant tumor of the larynx is squamous cell carcinoma. It grows from the mucous membrane lining the respiratory tract. Metastasis may occur to the lung.

Signs, Symptoms, and Diagnosis

The larynx (sometimes called the voice box) is directly involved with the production of vocal sounds. A tumor of the larynx will quickly produce persistent hoarseness that does not respond to usual methods of treatment.