CHAPTER 13. Sexual Assault Evidence Recovery

Jamie Ferrell and Cari Caruso

The science of forensic nursing is a distinctive specialty that provides exceedingly skilled healthcare professionals identified as forensic nurse examiners (FNEs) or sexual assault nurse examiners (SANEs) who practice nursing when health and legal systems intersect (Forensic Nursing Scope and Standards, 2009). These professionals are qualified to recognize and preserve the often fragile and perishable biological, trace, and physical evidence from crime scenes, whether in the field or in the hospital environs. The body becomes the identified crime scene as a result of sexual violence in both living and deceased victims. Without forensic clinicians, exceptional education, and specific forensic protocols, critical evidence is commonly lost or destroyed before it is recovered by emergency physicians, police, or forensic pathologists. The investigation of sexual violence requires a complex interplay of physical and testimonial evidence. This evidence is typically collected and interpreted by various professionals in nursing, medicine, law enforcement, mental health, and scientific disciplines.

The Joint Commission requires hospitals to have written criteria to identify those patients who may be victims of sexual assault, sexual molestation, or other forms of abuse. (The Joint Commission, 2009). The Joint Commission guidance also states that hospitals must assist these reported victims by either providing appropriate examinations for the reporting party or referring them to a private or public community agency that can provide these specialized services. In some jurisdictions, patients may be billed for a medical screening examination (MSE) if they initially present to a hospital, and are then transferred to a secondary site for the sexual assault examination.

Role of Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners

Sexual assault describes a wide variety of events, the definition of which varies significantly from state to state. Generally, sexual assaults involve some unwanted (nonconsensual) invasion of the victim, where the mouth, vagina, anus, and/or breast of the female victim and/or the mouth, penis, or anus of the male victim, offender, or both, are involved. In some states the term sexual battery is used.

The SANE is a vital member of the health delivery and evidence collection team in sex-related scenarios. SANEs are optimally prepared to assess the physical, emotional, and safety needs while simultaneously gathering evidence from the two most essential components of the crime scene: the bodies and personal effects of the victim and the offender or suspect.

SANEs who care for adult/adolescent patients usually receive the minimum of a 40-hour didactic course followed by a supervised 40- to 45-hour preceptorship. Some states have their own formal courses and their own certifications, which are typically required for nurses who have designated duties as SANEs. Occasionally, there is confusion between receiving a certificate for completion of a required course of study and the process of certification, which indicates competency. In most states and jurisdictions, one may practice with a certificate of course completion, but sitting for the formal certification examination is typically voluntary and suggests that successful candidates are expert practitioners in the specialty (see Chapter 51).

Advances in technology have enabled forensic scientists to reach far more positive conclusions from minute and seemingly insignificant items. A single hair or fiber, a microscopic particle of pollen, a drop of blood, or a single word in a statement can lead to the identity of a suspect and provide convincing evidence in court (Lynch & Ferrell, 2006). Criminalists and laboratory scientists have the right to expect that the evidence they analyze has been properly collected and preserved. The inclusion of the FNE/SANE as one member of the multidisciplinary investigative unit represents a growing trend in advancing the specifics necessary to reach correct conclusion (Lynch, 2006). This chapter addresses the guidelines developed by sexual assault specialists in the fields of healthcare, law, and forensic science.

Sexual Assault Medical/Forensic Examinations

Initial considerations

There are several ways for sexual assault patients to enter the healthcare system. One way is via the emergency department. Others may be initially encountered in clinics, physicians’ offices, or school health systems. Occasionally, law enforcement officers transport suspects or victims to a location staffed with a qualified SANE. Because all medical facilities do not have expert in-house personnel to perform the required examinations, many communities prefer the latter model. Most current sexual assault programs are aware of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) guidance, which outlines criteria if the sexual assault patient is to bypass the medical screening examination (MSE) and only have evidence collection in the emergency department.

“If an individual presents to a dedicated emergency department and requests services that are not for a medical condition, such as preventive care services (immunizations, allergy shots, flu shots) or the gathering of evidence for criminal law cases (e.g., sexual assault, blood alcohol test), the hospital is not obligated to provide a MSE under EMTALA to this individual.” (www.medlaw.com/searchpro/index.php?q=sexual+assault).

However, many facilities require an MSE because of the assaultive mechanism, the patient and clinician being unaware of any injuries until after the assessment is complete, and risk evaluation of pregnancy, STI and HIV exposure. Nevertheless, in the rare case that an individual has incurred obvious serious injuries and is in need of immediate medical attention, this takes priority over the sexual assault examination. Most patients, however, are physically stable and able to complete this voluntary examination process and to discuss the reported event.

Sexual assault patients exhibit diverse and complex needs based on age, gender, and acuity of the circumstance. Physical, psychological, financial, and legal issues are all priorities that must be considered in the plan of care for the patient. It is important to note that the lack of physical injury is not uncommon in the patient who reports a sexual assault. The role of the examiner is that of objectively providing exemplary nursing care and expert, competent evidence collection, and documentation for each patient. Documentation should include the history of the event from the patient, observations, findings, and the samples collected. It should not include opinion-based comments in the summary such as “no injuries consistent with sexual assault are noted”.

A stable patient should be placed in a private room as soon as possible, preferably away from the emergency department. Privacy, safety, and confidentiality must be ensured. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and other state medical privacy laws permit sharing of information in certain circumstances when the patient provides consent for dissemination or when law enforcement is involved. Covered entities and law enforcement agencies must collaborate to develop concise protocols for protected health information disclosure. State law will dictate whether information must be disclosed and to whom.

It is essential for nurses to have current knowledge of reporting mandates within their jurisdiction and to understand legalities regarding patient rights, consents for evidentiary examinations, and the guidelines for documentation and dissemination of information associated with the event. In most states, the sexually assaulted adult patient is not required to report the assault to law enforcement to be provided a medical/forensic examination. However, in all 50 states the sexual abuse of children is a mandated report to police or the child protection agency (Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act [CAPTA], 1996).

History of the event

The first step in a medical/forensic examination includes documenting the patient’s historical account of the assault. To assure accuracy and avoid misinterpretation, the patient’s statements must be documented in his or her precise words, enclosed in quotation marks. This initiates the diagnosis and treatment plan, is one component of the medical record, and is often a critical piece in the courtroom. The detailed physical examination that follows provides an opportunity to assess the body for health issues and as a potential crime scene. Most jurisdictions have a specific form to guide the examiner in obtaining the history of the sexual assault event.

The history of the sexual assault and the assessment provides information that will assist the examiner in collecting the right types of evidence from certain anatomical sites. For example, if the patient reports that he or she was physically restrained, there could be soft tissue defects including contact abrasions and contusions. Adhesive might remain from the use of duct tape, or bite marks might be detectable on the breasts. Written and photographic documentation should relate to the details provided by the patient history. Reports of oral, vaginal, or anal contact will determine areas of concentration for the detailed examinations of body orifices and the collection of specimens.

Sexual assault injuries

Early in the study of sexual assault, many believed that the examiner could assess the patient and determine whether the intercourse was consensual or nonconsensual. The absence of injury was commonly misinterpreted as a consenting adult. This belief was largely influenced by the 1966 study by Masters and Johnson, which described the body’s physiological response to consenting partner’s sexual stimulation. The study was used as an attempt to use the body’s response to consensual foreplay and stimulation to explain why lack of such stimulation may cause injury in nonconsensual intercourse. The theory was that that the reaction of the body would protect the woman from injury. There is no scientific basis to support the theory in relation to sexual assault cases. Stephen Johnston v. the Commonwealth of Virginia (2000) and Velasquez v. the Commonwealth of Virginia (2002) challenged the use of this theory for consent cases in court. Recent literature shows that there is little difference in the findings in consensual and nonconsensual intercourse (Anderson, McClain, & Riviello, 2006).

Severe physical injuries or genital trauma associated with sexual assault in an adult are considered to be atypical. However, if sadistic or masochistic tendencies are involved in the sexual act, injuries may be profound. If force has been inflicted, there will usually be evidence of such force on the body or clothes of the victim. Physical injury most commonly includes lacerations, contusions, bite marks, and broken fingernails. It should be noted that the presence of injuries does not necessarily equate to nonconsensual sexual activity or that the absence of injury negates the patient’s assertion of rape.

Drug-facilitated sexual assault

Professionals must also be alert to the prevalence of sexual assaults involving the use of drugs and alcohol. It is imperative that immediate action be taken to preserve evidence because of the rapid speed of the body’s metabolism. The most common substance used is alcohol (LeBeau, 1999). Drugs and alcohol can result in a loss of consciousness and an inability to resist. Some drugs cause memory loss and incapacitation even with the use of very unlikely drugs such as in the case of an adult male repeatedly using tetrahydrozoline (Visine) to induce a comatose state in an adult female and four female children for the purposes of sexual assault (Spiller, 2007). The effects of many drugs are enhanced when taken with alcohol. Patients who are impaired from the effects of drugs and alcohol often do not remember the assault. They may be found in public areas partially clothed. There are known cases where the individual is arrested for public intoxication without consideration that a sexual assault may have occurred, initiating the chain of events. Information that this might be a drug/alcohol sexual assault must be given to the forensic laboratory to ensure that the appropriate toxicological analyses are completed (see Chapter 10).

Consent for Examination

When applicable, written, informed consent should be obtained from adult patients before steps are taken to recover forensic evidence. Children under the age of 18 may require consent of parents or a guardian, depending on state law. Other states provide for examination with the consent of the minor only. If the hospital has a qualified pediatric forensic specialist or a certified pediatric sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE-P) on duty, that individual should be contacted for advice about consents, state reporting laws, or other medicolegal nuances associated with the scenario.

Occupational Health and Safety Issues

Alcohol-based hand hygiene products should not be used because these agents are ineffective in the presence of organic materials and degrade DNA on contact (Bjerke, 2004). A clean laboratory coat or disposable gown should be donned for each examination to prevent contamination from previous patients. Long hair should be restrained with a clip or the examiner should wear a disposable head covering (bonnet). Nails should be short to prevent puncturing the gloves. Acrylic wraps, nail polish, and artificial nails are not appropriate in the medical/forensic examination environment. Any rings, other than a smooth band ring, should be removed because they can create tiny, occult defects in the glove that obliterate its value as a protective barrier. Jewelry also tends to harbor soap, debris, and bacteria. Masks and face shields are required for cavity aspirations or any other procedure that could result in splash contamination (OSHA, 2009). Demonstrate precision by handling all evidence with gloved hands (preferably powder-free) and change gloves frequently.

Evidence Recovery Procedures

Evidence is any item, object, event, action, situation, or fact that aids in determining if a crime was or was not committed and who may or may not have committed the crime (National Institute of Justice, 2004a). It is not the role of the FNE to make this determination nor to draw a conclusion as to whether or not rape has occurred. The FNE is only responsible for identifying and documenting injury and recovering potential evidence during the assessment.

Many states have designated evidence collection kits that are used to assist in the collection and preservation but are not intended to dictate or limit what must be collected. Collecting samples for DNA analysis at crime scenes is a critical part of investigating the nature of the crime (National Institute of Justice, 2004b).

A primary goal is to avoid the loss, contamination, or damage of physical evidence. Therefore, any personal items should not be immediately given to the patient’s friends or family. Do not bathe the patient or discard, clean, or wash the patient’s personal items. Do not cut through holes, stains, or other defects in the patient’s clothing. Be careful to collect all evidence individually and maintain items in one’s personal possession or secure the area where the evidence will be kept. It is imperative to communicate to appropriate personnel if any item of evidence has been accidentally contaminated during the collection or packaging processes. Potential contamination can be minimized by ensuring that the examination room is meticulously cleaned between patients and is well organized and properly equipped. Wearing appropriate personal protective clothing will also prove to be a valuable safeguard against accidental contamination by the examiner who may disperse saliva by talking, coughing, or sneezing. Obviously, smoking, food, and drinks should not be permitted in the examination room at any time.

It may be necessary to contact police to provide a prompt transfer of evidence from the hospital to the crime laboratory to protect certain evidence from degradation. Custody of the evidence is the responsibility of the FNE/SANE until transfer. Unfortunately, police may fail to provide timely recovery and transfers. During long delays, there may be degradation of certain specimens. Moist or damp articles of clothing should be air-dried in a secure area until the transfer is completed. The hospital is responsible for the custody of evidence and should have a designated evidence custodian. Ideally, this is a FNE who is familiar with policies and procedures regarding the preservation, security, and legal issues pertaining to evidentiary items.

Evidence collection with injury

Unique challenges must be considered when bleeding injuries complicate evidence recovery. Collecting the best specimen remains the objective. In clinical practice, cleaning and preparing a wound for a dressing is not evidence recovery, and if the patient is stable, evidence should be collected first. For example, a bite mark causing bleeding should be swabbed where the lips of the suspect made contact with the skin above, below, and in the middle of the injury before performing other wound care. This will provide for the best sample to distinguish deposited DNA from the patient’s blood. When extreme genital injuries are present, evidence recovery is complicated. If a severe vaginal tear exists in certain anatomical locations, the optimum ejaculate specimen may have been washed out of the vaginal vault with the flushing of the blood. In this type of scenario, one might consider collecting the entire blood trail beginning from the end of the trail and proceeding upward with a 4-by-4-inch gauze moistened with sterile water. This can be repeated for each anatomical structure such as foot, lower leg, or thigh until collection is complete to the vaginal vault. These gauze wipes will need to air-dry and be packaged individually, sealed, and labeled as noted in later sections. Unusual circumstances affecting evidence collection and preservation will occur. It is sensible in these situations to consult a law enforcement evidence technician or a crime laboratory analyst for suggestions.

Evidence recovery during menstruation

If patients are menstruating, collect tampons and sanitary napkins. Air-dry them as much as possible and then place them in a separate paper collection bag. Wet evidence that cannot be dried thoroughly at the exam site should then be packaged in leak-proof containers and separated from other evidence. This must be communicated when being signed over to law enforcement.

Physical evidence

Tangible evidence has a collective significance in the criminal and civil investigation of sexual violence. The nature of trace or “transfer” evidence is highly variable and can be found at almost every crime scene. Trace evidence can include hair, fiber, glass, soil, and other particulate matter. The media has highly influenced the public’s perception about crime scene investigations and the role of evidence in legal proceedings. This immersion in crime scene investigations through television programs such as CSI has also raised expectations of those who identify, collect, and process evidence. Most states have patterned their policies and procedures for consistency with the laboratory standards of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). However, the SANE must be aware of variations within the state or local jurisdiction.

Biological evidence

Sources of potential biological or genetic evidence are continually expanding with advances in scientific analysis and testing of materials that might be suitable for DNA typing. DNA is contained in all body tissue fluid and cells, with the exception of white blood cells (McClintock, 2008). FNEs are not mandated to collect DNA evidence but rather obtain body fluids or tissues that might contain DNA. Among these are blood and blood stains, semen, saliva, hair roots, bone, teeth, and tissue. Similar to perspiration or sebaceous secretions, urine also contains enough epithelial material to generate a DNA profile (McClintock, 2008). Swabbings of the oral or vaginal cavity as well as bite marks (see Chapter 26) can be used to recover DNA. Certain items of physical evidence collected at the scene of the crime may also contain DNA. Examples are cigarettes, toothpicks, bottles or cans, bullets, condoms, ligatures, clothing, knives, and other weapons.

Biological evidence possesses its greatest value in investigations where DNA types can be compared to known profiles obtained from either the victim or the suspect. The investigation efforts may occur over several years, so precise documentation, record keeping, and specimen management are imperatives. It is important, therefore, to collect the samples on a medium that can stabilize the genetic material. The use of an FTA collection card permits both short- and long-term storage of biological specimens at room temperature (FTA is a registered trademark of Flinders Technologies, Pty. Ltd.). This card is made from an absorbent cellulose-based paper that contains chemical substances to inhibit bacterial growth and to protect the DNA from enzymatic degradation. Samples such as blood and saliva can be “spotted” onto this collection card for storage up to 17 years (McClintock, 2008). These cards are preferred for collecting offender DNA samples for inclusion into forensic databases.

Certain biological materials such as semen and urine require refrigeration or freezing. The local crime laboratory will provide guidance for these and other specimens such as hair, bone, teeth, and body tissue. To avoid cross-contamination of evidence that may contain DNA, the forensic examiner must take precautions to wear a mask and to do frequent handwashing and glove changes throughout the examination.

Photographic Documentation

Forensic photography is an essential method for documenting evidence and injury. Evidence must be photographed in situ before it is recovered from a crime scene or from the body. Digital photography is the preferred method for recording evidentiary photographs because the images can be reviewed immediately and retaken if necessary to ensure that important details are captured. The images can be downloaded onto a computer and reproduced for use in the courtroom.

Distant range photos showing the location of apparent injuries should be taken as an orientation shot. Next, midrange and finally, close-up photos should be taken with an American Board of Forensic Odontology (ABFO) #2 Grey Scale in place. This is the preferred scale and is valuable for use in bite mark and other injury/evidence documentation (Olshaker, 2007). A coin or another object of a known size may be used if the examiner does not have access to the specified photographic scale. Many photographs may be required to fully document injuries over the body surfaces and to record precise findings within the mouth and the genital/anal areas. Colposcope-mounted cameras may be employed to magnify and document certain findings but the above forensic photography principles would not be applicable due to the magnification and sensitivity of the genital images (see Chapter 7, Fig. 7-11).

Alternate Light Source (ALS)

Forensic nurse examiners may employ ultraviolet (UV) and infrared (IR) technology to document injuries that are not easily seen by the naked eye. Hidden details of a deep bruise may be revealed using UV technology, whereas details of an incised wound can be better appreciated with IR technology (Klingle & Reiter, 2008). Hospitals or law enforcement agencies may supply these helpful adjuncts to aid the FNE in detection and documentation of bruises, fingerprints, and soft tissue defects. Before using any ALS, the forensic examiner should be well versed in the techniques for using these devices, including assets and limitations of the various UV or IR technologies. Both the examiner and the patient must wear a suitable type of safety goggles if these ALS adjuncts are used to document injuries during the course of a forensic examination (Klingle & Reiter, 2008). The use of eye protection should be annotated in the patient’s record to protect the nurse and the hospital from liability-associated eye injuries. (See Chapter 7 for a complete discussion of forensic photography and alternate light sources.)

Methods of Evidence Recovery

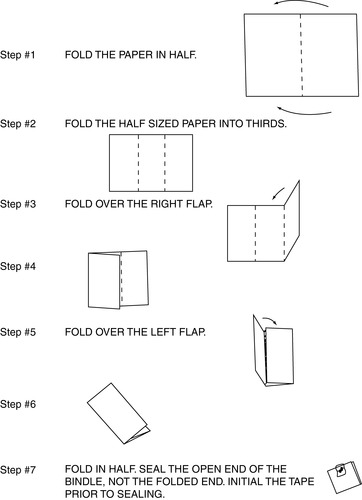

Sexual assault evidence collection will vary depending on local crime laboratory testing methodologies, protocol, and the choice of kits. The kit itself should never be the predictor or limiting hindrance of appropriate evidence collection for any victim of sexual assault. The collection kit is provided as a tool to assist the FNE with packaging the best specimens. When collecting evidence onto paper, use a clean piece of paper and fold into a bindle (Fig. 13-1).

Clothing

A vital part of evidence collection is the patient’s clothing. Clothing worn by the victim at the time of the sexual assault is often found to have physical or biological evidence that needs to be preserved. If clothes have been changed, collect the clothing items that remain next to the body areas affected. This is most commonly the underwear and in many cases the bra or undershirt. Case studies are demonstrating significant value with DNA results from the bra because of saliva on the breasts. Look briefly at the clothing and describe the presence of any stains or tears. A more detailed inspection will be done in the forensic laboratory. Clothing preservation can be facilitated by first placing a clean sheet or piece of table paper on the floor to act as a barrier. Then place a second sheet or layer of table paper on top of the barrier and have the patient disrobe over it. Carefully drop each item of clothing at a separate location on the sheet/paper, making sure to not to commingle clothing items in a single pile (Ferrell, 2007).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access