Linda Thompson Adams and Deborah M. Tierney*

Policy, Politics, Legislation, and Community Health Nursing

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Discuss the nurse’s role in political activities.

2. Discuss the power of nursing to influence and change health policy.

3. Identify the social and political processes that influence health policy development.

5. Discuss current health policy issues, including restructuring of the health care system.

Key terms

administrative agencies

Clara Barton

coalition

Florence Nightingale

government

health policy

institutional policies

Lavinia Dock

Lillian Wald

lobby

lobbyist

Mary Wakefield

nursing policy

organizations

organizational policies

policy

policy analysis

political action committees

politics

public health law

public policy

Ruth Watson Lubic

social policy

Sojourner Truth

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

Introduction to health policy and the political process

This chapter addresses the interrelationships of the processes through which health policies are determined and instituted. Politics and legislation are the routes through which public health policies are established. Policy, politics, and legislation are the forces that determine the direction of health programs at every level of government, as well as the private sector. These programs are crucial to the health and well-being of the nation, the state, the community, and the individual. Nurses influence the maintenance and improvement of the health of individuals, groups, and communities by contributing to policy and legislative advancement.

The health care delivery system, including nursing practice and research, is profoundly influenced by policies set by both government and private entities. Nurses who understand the system of health policy development and implementation can effectively interpret and influence policies that affect nursing practice and health of individuals, families, groups, and communities.

The more a nurse knows about the political process, the more he or she tends to become involved. Individual nurses may become politically active on a local, state, or national level. Nurses may work collectively within a group such as the National Student Nurses Association, the American Nurses Association (ANA), and state boards of nursing to lobby for health causes. The profession of nursing is about 3 million strong (ANA, 2009; HRSA, 2010), and together nurses can be patient advocates, change agents, and policy makers. Nurses are respected by lawmakers and act as consultants in both the legislative and executive branches. It is the hallmark of the U.S. system of government that citizens have the right to have an influential voice in the governance of the community. Nurses are able to communicate concerns about conditions and issues in health care, the health care needs of individuals and communities, as well as the profession of nursing. United, nurses can influence political leaders to make changes to the health care system that are beneficial to all. Experienced nurses in the political arena can mentor novice nurses. Many individual nurses in the past and present have been instrumental in working with legislation and politics. Information on a few exemplary nurse heroines who illustrate this point follows:

• Florence Nightingale was the first nurse to exert political pressure on a government (Hall-Long, 1995). She transformed military health and knew the value of data in influencing policy. She was a leader who knew how to use the support of followers, colleagues, and policy makers.

• Sojourner Truth became an ardent and eloquent advocate for abolishing slavery and supporting women’s rights. Her work helped transform the racist and sexist policies that limited the health and well-being of African Americans and women. She fought for human rights and lobbied for federal funds to train nurses and physicians (Mason, Leavitt, and Chaffee, 2007).

• Clara Barton was responsible for organizing relief efforts during the U.S. Civil War. In 1882, she successfully persuaded Congress to ratify the Treaty of Geneva, which allowed the Red Cross to perform humanitarian efforts in times of peace. This organization has had a lasting influence on national and international policies (Hall-Long, 1995; Kalisch and Kalisch, 2004).

• Lavinia Dock was a prolific writer and political activist. She waged a campaign for legislation to allow nurses to control the nursing profession instead of physicians. In 1893, with the assistance of Isabel Hampton Robb and Mary Adelaide Nutting, she founded the politically active American Society of Superintendents of Training School for Nurses, which later became the National League for Nursing (Kalisch and Kalisch, 2004). She was also active in the suffrage movement, advocating that nurses support the woman’s right to vote (Lewinson, 2007).

• Lillian Wald’s political activism and vision were shaped by feminist values. Working in the early 1900s, she recognized the connections between health and social conditions. She was a driving force behind the federal government’s development of the Children’s Bureau in 1912. Wald appeared frequently at the White House to participate in the development of national and international policy (Mason et al., 2007).

• Dr. Ruth Watson Lubic is a nurse-midwife who crusaded for freestanding birth centers in this country. After realizing the birth center model through the Maternity Center Association in New York City, Dr. Lubic expanded the model to Washington, DC, where the infant mortality rate was twice the national average. In 1993, Lubic was awarded the MacArthur Fellowship Grant and, in 2001, the Institute of Medicine’s Lienhard Award (Institute of Medicine, 2001; Lyttle, 2000).

Definitions

Policy denotes a course of action to be followed by a government, business, or institution to obtain a desired effect. The Merriam-Webster definition is “a definite course or method of action selected from among alternatives and in light of given conditions to guide and determine present and future decisions.” Policy encompasses the choices that a society, segment of society, or organization makes regarding its goals and priorities and the ways it allocates its resources to attain those goals. Policy choices reflect the values, beliefs, and attitudes of those designing the policy (Mason et al., 2007).

Public policy denotes precepts and standards formed by governmental bodies that are of fundamental concern to the state and the whole of the general public. The field of public policy involves the study of specific policy problems and governmental responses to them. Political scientists involved in the study of public policy attempt to devise solutions for problems of public concern. They study issues such as health care, pollution, and the economy. Public policy overlaps comparative politics in the study of comparative public policy, with international relations in the study of foreign policy and national security policy, and with political theory in considering ethics in policy making. See the example in Table 12-1.

TABLE 12-1

| Topic | Example |

| Public policy | A local or regional effort to prevent the sale of tobacco or alcohol to minors. Public policy directs that the right to health of the majority must be preserved over individual freedoms and corporate interests. |

| Public health law | New York State Public Health Law §2164: “Every person in parental (statute) relation to a child in this state shall have administered to such child an adequate dose of an immunizing agent against poliomyelitis, mumps, measles, diphtheria, rubella, varicella, Haemophilus influenza type B, and hepatitis B…” |

| Common law | The Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade, making first-trimester abortion legal, is an example of how common law becomes enforceable. |

| Regulation | Reporting communicable diseases to the state and local health departments, which then report them to the CDC. |

| Treaty | Multilateral treaty: Treaty to eliminate all forms of discrimination against women |

Health policy is a statement of a decision regarding a goal in health care and a plan for achieving that goal. For example, to prevent an epidemic, a program for inoculating a population is developed and implemented, and priorities and values underlying health resource allocation are determined.

Nursing policy specifies nursing leadership that influences and shapes health policy and nursing practice. Nursing, and therefore nursing leadership, is shaped dramatically by the impact of politics and policy. Effective nursing leadership is a vehicle through which both nursing practice and health policy can be influenced and shaped.

Institutional policies are rules that govern work sites and identify the institution’s goals, operation, and treatment of employees.

Organizational policies are rules that govern organizations and their positions on issues with which the organization is concerned (Mason et al., 2007).

Social policy is policy associated with individuals and communities. In very general terms, social policy can be defined as the branch of public policy that advances social welfare and enhances participation in society. Social safety nets, however, often contribute to social exclusion, especially in urban settings, instead of being universally accessible. In most Western societies, social protection usually depends on contributory social insurance schemes to which only regular job holders have access (either in their own right or as dependents). In the United States, this is particularly evident with respect to the way the health care system and Social Security retirement benefits work.

Social justice argues that all individuals and groups receive fair treatment in society, as well as impartially sharing in the benefits of that society (Almgren, 2007).

Administrative agencies are departments of the executive branch with the authority to implement or administer particular legislation.

Laws are rules of conduct or procedure; they result from a combination of legislation, judicial decisions, constitutional decisions, and administrative actions.

Public health law focuses on legal issues in public health practice and on the public health effects of legal practice. Public health law typically has three major areas of practice: police power, disease and injury prevention, and the law of populations. Statute, ordinance, or code prescribes sanitary standards and regulation for the purpose of promoting and preserving the community’s health. Public health law consists of legislation, regulations, and court decisions enacted by government at the federal, state, and local levels to protect the public’s health. This includes case law and treaties.

Statutes are any laws passed by a legislative body at the federal, state, or local level.

Organizations are associations that set and enforce standards in a particular area; a group of individuals who voluntarily enter into an agreement to accomplish a purpose.

A professional association (also called a professional body, professional organization, or professional society) is a nonprofit organization seeking to further a particular profession, the interests of individuals engaged in that profession, and the public interest. It is a volunteer group that seeks to join large numbers of individuals who have a significant wealth of knowledge and experience in a particular field. There are also pooled funds for lobbying purposes (Thomas, 1997). The roles of these professional organizations are viewed as maintaining the control and oversight of the professional occupation, as well as safeguarding the public trust. There is an element of protecting the interests of the professional practitioners, similar to a cartel or labor union. Inherent in these organizations is the promotion of general standards for the performance of its members and the expectation of continued professional development.

Many professional bodies are involved in the development and monitoring of professional educational programs and the updating of skills, and thus perform professional certification to indicate that a person possesses qualifications in the subject area. Sometimes membership of a professional body is synonymous with certification, though not always. Membership of a professional body, as a legal requirement, can in some professions form the primary formal basis for gaining entry to and setting up practice within the profession. Professional bodies also act as learned societies for the academic disciplines underlying their professions.

Nongovernmental organizations are international organizations that use donations and grants to assist communities in need, with minimal support from, or influence of, a particular nation.

Healthy People 2020

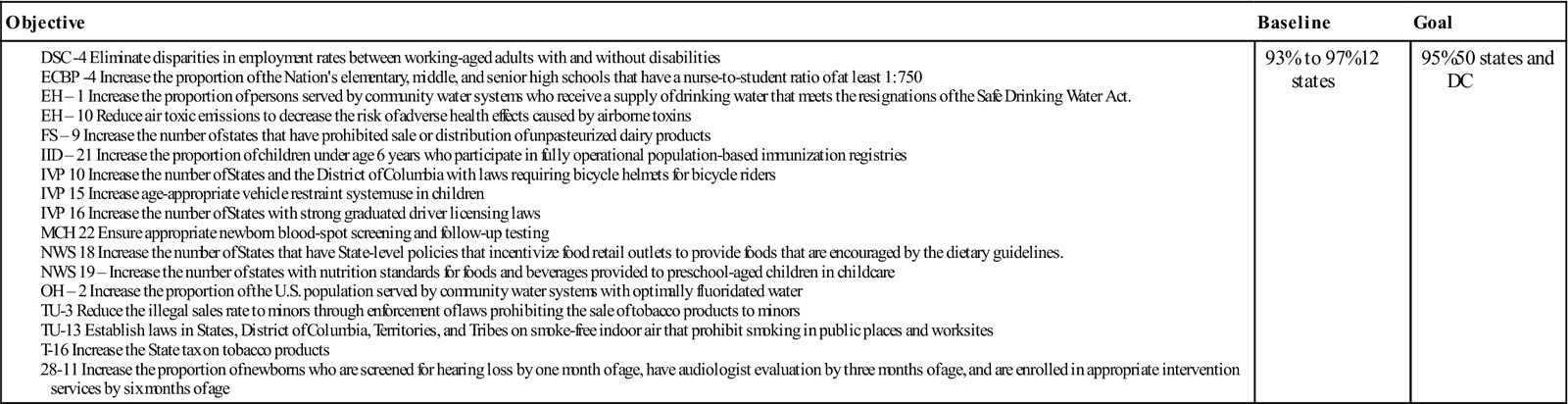

The publication of Healthy People 2000 by U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop in 1990 led to a resurgence of interest by the federal government in the health and welfare of Americans. However, fiscal resources for public health interventions declined, and only marginal progress was made in meeting the goals. In early 2000, Healthy People 2010 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2009) marked the beginning of the new millennium and an enhanced focus on population-based health promotion strategies. Many Healthy People 2010 objectives directly or indirectly involved health policy. The most recent update, Healthy People 2020 (USDHHS, 2009) enhances the focus on the social determinents of health and adds even greater emphasis on health policy (Healthy People 2020 box).

Virtually all of the areas of Healthy People 2020 have multiple policy-related objectives, and the Healthy People box lists only a few of them. Building on previous iterations, the updated draft version has four “over-arching goals” for 2020: attain high quality, longer lives free of preventable disease, disability, injury, and premature death; achieve health equity, eliminate disparities, and improve the health of all age groups; create social and physical environments that promote good health for all; and promote quality of life, health development, and health behaviors across all life stages. Another forward-looking recommendation is making Healthy People 2020 into a Web-accessible database that is searchable and interactive and will allow users to tailor the document to the public’s needs. The intent is that enhanced focus on social determinants represents a “deliberate shift away from the perception that access to health care services will ever solve all of our health care problems” (USDHHS, 2009).

Structure of the government of the united states

Government is the structure of principles and rules determining how a state, country, or organization is regulated. Among its purposes are regulation of conditions beyond individual control and provision of individual protection through a population-wide focus. These tasks are accomplished through passage and enforcement of laws. Requirements of childhood immunizations for school attendance, vector control, and sewage treatment are examples of regulations to protect the health of the population.

Government can also be viewed as the sovereign power vested in a nation or state. Sovereign power is the independent and supreme authority of the nation or state. Historical documents describe the government’s responsibility for health in the United States and the subsequent authority to enact laws (including health laws). These documents reflect the values of the country’s founders. They give the government the authority to enact laws, but they also limit that power. The earliest of these statements was the Mayflower Compact, through which the Pilgrims committed themselves to making “just and equal laws” for the general good. The Declaration of Independence later established the doctrine of inalienable rights, life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. However, it was not until the Constitution of the United States was signed by the representatives of the individual states that the federal government realized its sovereign power. At the same time that power was realized, a limit to that power was placed on the federal government. The drafters of the Constitution sought to balance the need to empower the new federal government to “establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty” for its people but with limits on that power. That balance is achieved in several important ways.

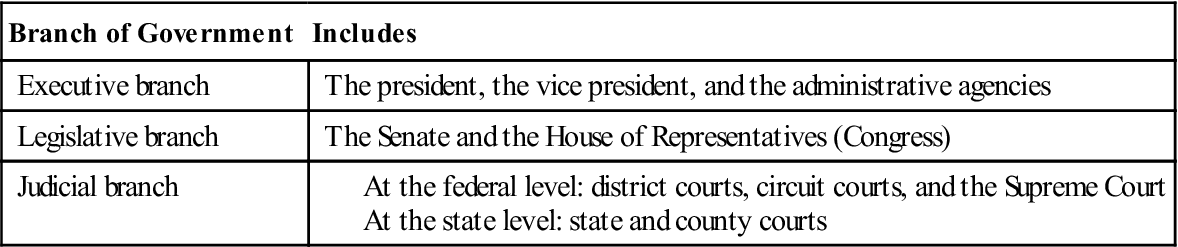

The federal government is a government of limited powers, which means that for a federal action to be legitimate, it must be authorized. Only those actions that are within the scope of the Constitution, the supreme law of the land, are authorized. The Constitution separates governmental powers among the branches of government (Table 12-2).

TABLE 12-2

Some examples of the separation of powers doctrine that are written into the U.S. Constitution include the following:

• The legislature is prohibited from interfering with the courts’ final judgments.

• The Supreme Court cannot decide a “political question”; it must be an actual case or controversy.

• Congress must present a bill to the President before it can become law (Box 12-1).

• The President needs consent of the Senate to appoint Supreme Court Justices or to make treaties.

• The President and members of Congress are elected; the Judiciary is appointed.

The Constitution not only set forth the responsibilities of the federal government, but it also provided for the individual citizen’s rights and freedoms. These are contained in the ten amendments, which were added after the original Articles of the Constitution were ratified in 1787. These ten amendments, added in 1791, are known as the Bill of Rights. The rights guaranteed in the Bill of Rights, such as the rights of free speech and freedom of religion, only applied to the laws and actions of the federal government. It would take another 72 years for these rights to be guaranteed within the states. “Liberty interests” and “privacy rights” have been found to exist by determinations by the Supreme Court and have become guiding principles in setting policy and enacting legislation. Note that these rights are only applicable to state or federal government’s interaction with people. Violations of restrictions on rights such as free speech do not apply to nongovernmental entities, unless a specific law states otherwise.

Balance of Powers

Federalism is the relationship and distribution of power between the national and the state governments. This balance flows directly from the text of the Constitution: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

States retain powers not delegated to the federal government; therefore much of public health law is under state jurisdiction and, as a result, varies considerably from state to state. These powers to enact laws for the public welfare are referred to as the states’ “police powers.” Additionally, states may delegate these powers to local governments. In the United States, legislative activities of the three levels of government (federal, state, and local) may vary greatly in their expectations, actions, and results. The state legislatures, for the most part, are directly involved in health care, yet the federal government influences health policy, directly and indirectly, through the financing of health care for many groups (e.g., Medicare), regulation activities (e.g., approval of drugs), and setting of standards (e.g., air quality).

Decisions affecting the public’s health are made not only at every level of government but also in each branch of government. The separation and balance of powers, referred to as checks and balances, is as important to health as it is to the economic or military status of the country.

The legislative branch (i.e., Congress at the federal level; legislature, general assembly, or general court at the state level) enacts the statutory laws that are the basis for governance. The executive branch administers and enforces the laws, which are broad in scope, through regulatory agencies. These agencies, in turn, define more specific implementation of the statutes through rules and regulations (i.e., regulatory or administrative law). The judiciary body provides protection against oppressive governance and against professional malpractice, fraud, and abuse. Its function, through the courts, both state and federal, is to determine the constitutionality of laws, interpret them, and decide on their legitimacy when they are challenged. Decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court are binding law for the nation. Decisions of the individual state’s highest court are binding law within that state alone. The courts also have jurisdiction over specific infractions of laws and regulations.

The legislative process

How a Bill Becomes a Law

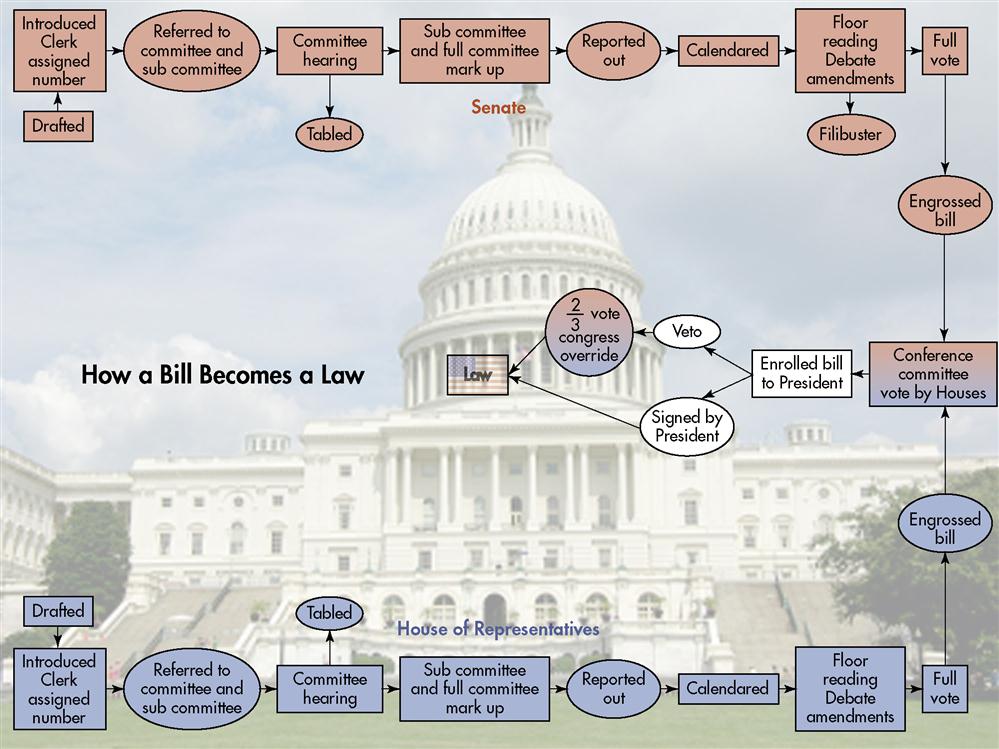

As stated in the previous section, there is a balance of powers within the government at both state and federal levels. The three branches of government, executive, judicial, and legislative, form a three-legged stool that is in equilibrium. Along with a separation of powers of the three branches of government, there is an additional mechanism that balances the power of the Congress: bicameralism. Bicameralism ensures that the power to enact laws is shared between the House of Representatives and the Senate. The procedure through which legislation must pass to eventually become law is similar for all U.S. legislative bodies. Once a concept has been drafted into legislative language, it becomes a bill, is given a number, and moves through a series of steps. The bill’s passage is sometimes smooth, but, more often than not, the bill is extensively altered through amendments or even killed.

In Congress and in the 49 states that have a two-house legislature, a bill must succeed through the two legislative bodies, that is, the House of Representatives and the Senate (Figure 12-1). Nebraska, which has a single-house legislature, is the exception. A bill that has moved successfully through the legislative process has one final hurdle, which is the chief executive’s approval. The approval may be a clear endorsement, in which case the governor or president signs it. If the executive neither signs nor vetoes it, the bill may become law by default. An explicit veto conclusively kills the bill, which then can be revived only by a substantial vote of the legislature to override the veto. This is another example of the checks and balances of the government process.

Issues that find their way into the legislative arena are commonly controversial, and proponents and opponents quickly align themselves. Defeating a bill is much easier than getting one passed; therefore the opposition always has the advantage. Health legislation, which usually requires preventive action (e.g., toxic waste management) or creates a new service (e.g., nursing center organizations for Medicare recipients), is at a disadvantage from several standpoints.

Few elected officials are knowledgeable about the health care field. Although health is readily recognized as a national resource, it is not easily quantified into the economic terms that make the issue easy to grasp. Other disadvantages are the backgrounds, biases, and ambitions of each legislator. Despite these obstacles, good health laws can be passed when concerned nurses and other health care workers understand the legislative process and use it effectively. Nurses should educate their elected officials and be expert tutors for them. In addition, this is yet another mode of intervention on behalf of clients for nurses. Legislation passed to reduce or prevent abuse for all children is as important as physical and emotional care of the abused child.

Overview of health policy

Public Health Policy

To review, public policy refers to decisions made by legislative, executive, or judicial branches of one of the three levels of government (local, state, or federal). These decisions are intended to direct or influence actions, behaviors, or decisions of others. Public health policies influence health care through the monitoring, production, provision, and financing of health care services.

Everyone, from health care providers to consumers, is affected by health policies. Likewise, health policy influences corporations, employers, insurers, colleges of nursing, hospitals, clinics, producers and retailers of medical technology and equipment, as well as senior care facilities.

The authority for the protection of the public’s health is largely vested with the states, and most state constitutions specifically delineate their responsibility. Municipal subdivisions of states, such as counties, cities, or towns, generally have the power of local control of the services conferred by the state legislature. The responsibility of local, state, and federal governments for health services under varying circumstance sometimes complicates attempts to determine the locus of political decision making. The supremacy of the state prevails in most instances; therefore the state is a critical arena for political action. An example is the state’s authority to license health professionals and health care institutions.

Each state establishes policies or standards for goods or services that impact the health of its citizens. However, if the federal government or the local government imposes a higher standard than the state requires, the lower standard is negated by the higher standard. An example would be standardization of pasteurized milk. A state may hold to one standard whereas interstate commerce of the federal jurisdiction may dictate a higher standard that must be met by that state.

The federal government has a strong influence on the health services available in each state. Constitutionally, this authority is derived from the federal role in interstate commerce and through broad interpretation of the “general welfare” clause (e.g., Medicare and Medicaid). States vary considerably in resources allocated to provide health programs; therefore significant de facto authority derives from the promise of revenues or threats to remove funding (e.g., funds for interstate highway repair are often tied to air quality requirements). Federal funds typically fully or partially fund most health care programs.

Compliance by states with federal program standards is voluntary, but the advantage of the revenue, which is withheld from the states that fail to comply, is seldom ignored. Programs such as a statistical reporting system of sexually transmitted infections and control are standardized across the country in response to the indirect but marked effect of federal funding.

Health Policy and the Private Sector

In addition to the public policy making sector, health policies can also be made through the private sector. For example, an insurance company or an employer will determine what illnesses and preventative care will be covered by the insurance program, what drugs are included in the formulary, and how much to charge for an insurance policy. The private sector includes employers, professional organizations (e.g., American Hospital Association), nonprofit health care organizations (American Heart Association), and for-profit corporations that deliver, insure, or fund health care services outside of government control. In particular, health insurance companies and managed care organizations (MCOs) are increasingly setting policies that impact a large number of individuals.

In the private sector, health policy evolves differently than in the public sector. One difference is that private health policy is largely influenced by theories of economics and business management as compared with the social and political theories that predominate in the public sector. In the private sector economics is central, whereas in the public sector economics is but one of many factors. In the private sector decisions can be swift and are often proactive, whereas in the public sector decisions are slow and deliberate, and more reactive. Private sector needs are determined by consumerism, market trends, and economics. Public sector needs are determined by voting shifts, electoral realignment, and term limits (Pulcini et al., 2000). Box 12-2 provides the history of government-funded health care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Healthy People 2020

Healthy People 2020